Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

22281

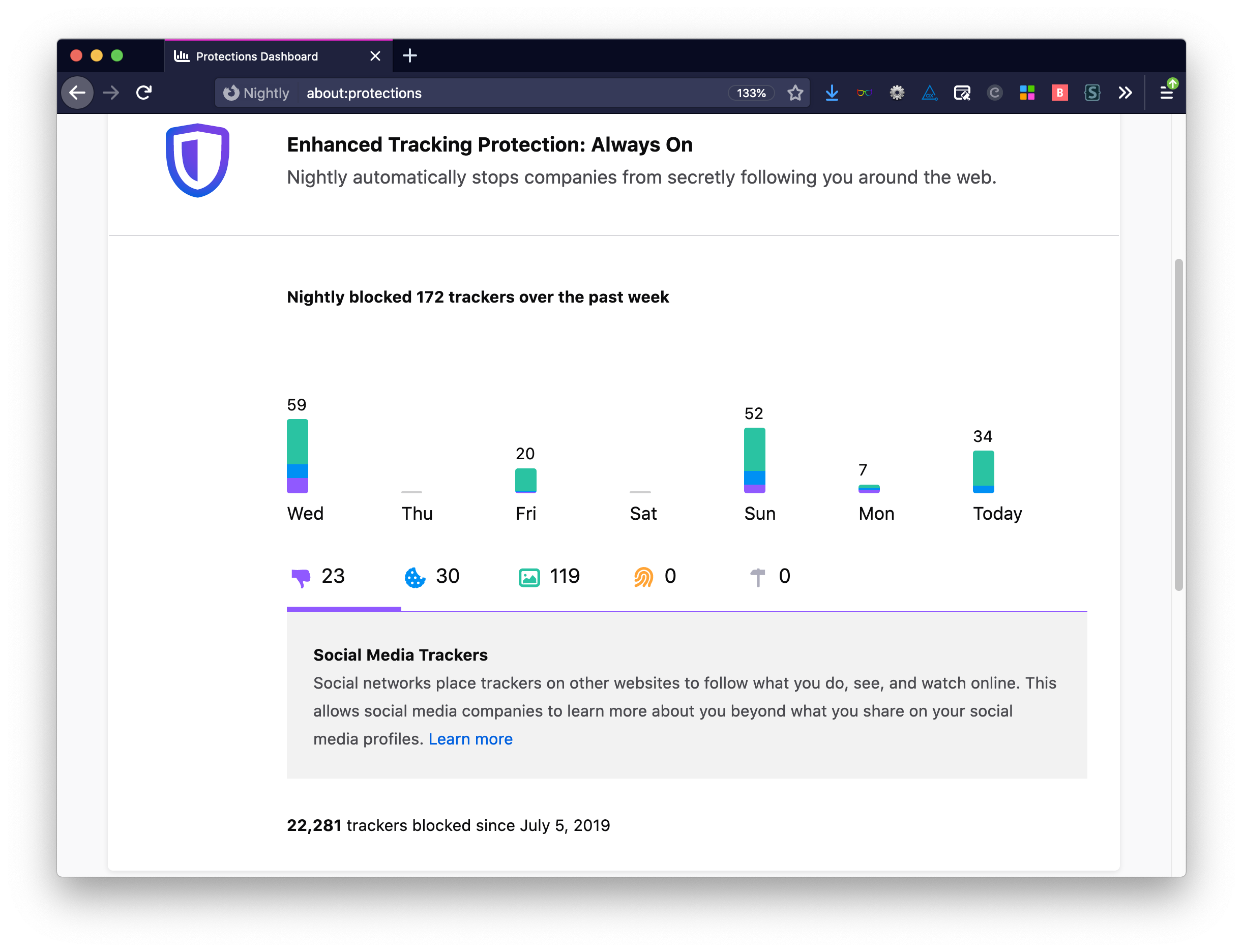

In July 2019, my main browser of choice, Firefox Nightly, landed a new dashboard. It shows how much was blocked by the browser’s tracking protection feature. This can be found in about:protections. Let’s look at the stats after this first year.

Tracking protection is essential on today’s web. It’s a feature that both Firefox (Enhanced Tracking Protection) and Safari (Intelligent Tracking Protection) have had for quite some time now. Most websites are still full of naughty scripts that pass on information to social media giants, track you across websites, exercise finger printing and even mine crypto currencies.

I use the “Strict” mode in Nightly, which comes with a warning: ‘causes some sites to break’. I don’t recall ever seeing sites break at all, but your mileage may vary. Where it does happen, an exception can be made for a specific site.

The dashboard in about:protections tells you what types of trackers were blocked over the past week, as well as a total since you started using the future. After just over a year, mine shows 22281 trackers since July 5, 2019.

Like I’m excited browsers can fix accessibility problems, I’m grateful that they help address this problem when many websites don’t. It’s time for more minimum viable data collection. Happy birthday, tracking protection dashboard!

Reply via email

22281

In July 2019, my main browser of choice, Firefox Nightly, landed a new dashboard. It shows how much was blocked by the browser’s tracking protection feature. This can be found in about:protections. Let’s look at the stats after this first year.

Tracking protection is essential on today’s web. It’s a feature that both Firefox (Enhanced Tracking Protection) and Safari (Intelligent Tracking Protection) have had for quite some time now. Most websites are still full of naughty scripts that pass on information to social media giants, track you across websites, exercise finger printing and even mine crypto currencies.

I use the “Strict” mode in Nightly, which comes with a warning: ‘causes some sites to break’. I don’t recall ever seeing sites break at all, but your mileage may vary. Where it does happen, an exception can be made for a specific site.

The dashboard in about:protections tells you what types of trackers were blocked over the past week, as well as a total since you started using the future. After just over a year, mine shows 22281 trackers since July 5, 2019.

Like I’m excited browsers can fix accessibility problems, I’m grateful that they help address this problem when many websites don’t. It’s time for more minimum viable data collection. Happy birthday, tracking protection dashboard!

Originally posted as 22281 on Hidde's blog.

How deployment services make client-side routing work

Recently I deployed a Single Page Application (SPA) to Vercel (formerly Zeit). I was surprised to find that my client-side routes worked, even though my deployment only had a single index.html file and a JavaScript routing library. Here’s which ‘magic’ makes that possible, for if you ever end up needing the same.

How servers serve

In the most normal of circumstances, when we access a web page by its URL, it is requested from a server. This has worked since, I believe, the early nineties (URLs were more recently standardised in the URL spec). The browser deals with that for us, or we can do it in something like curl:

curl GET https://hiddedevries.nl/en/blog/We tell the server “give me this page on this host”. To respond, the server will look on its file system (configs may vary). If it can find a file on the specified path, it responds with that file. Cool.

Now, If you have a Single Page App that does not do any server side rendering, you’ll just have a single page. This is, for instance, what I deployed:

public

- index.html

- build

- bundle.js

- bundle.css

- images

- // imagesLet’s say I deployed it to cats.gallery. If someone requests that URL, the server looks for something to serve in the root of the web server (or virtual equivalent of that). It will find index.html and serve that. Status: 200 OK.

Client side routes break by default

Our application is set up with client side routing, but, for reasons, we have no server side fallback (don’t @ me). It contains a div that will be filled with content based on what’s in the URL. This is decided by the JavaScript, which runs on the client, after our index.html was served.

For instance, there is cats.gallery/:cat-breed, which displays photos of cats of a certain breed.

A British shorthair - photo by Martin Hedegaard on Flickr

A British shorthair - photo by Martin Hedegaard on Flickr

When we request cats.gallery/british-shorthair, as per above, the server will look for a folder named british-shorthair. We’ve not specified a file, the server will look for index.html there. No such luck, because we created no fallback, there’s just the single index.html in the root. If servers don’t find anything to serve, they’ll serve an error page with the 404 status code.

It does matter how we’ve loaded the sub page about British shorthairs. Had we navigated to cats.gallery and clicked a link to the British shorthair page, that would have worked, because the client side router would have replaced the content on the same single page.

How do they make it work?

One way to fix the problem, is to use hash-based navigation and do something like cats.gallery/#british-shorthair. Technically, we’re still requesting that index.html in the root, the server will be able to serve it, and the router can figure out that it needs to serve cats of the British shorthair breed.

But, we want our single page app to feel like a multi page app, and have “normal” URLs. Surprisingly, this still works on some services. The trick they need to do is to serve the index.html file that’s in our project’s root, but for any route. Want to see British shorthairs? Here’s index.html. Want to see Persian cats? Look, index.html. Returning to the home page? index.html for you, sir!

Vercel

Vercel does this automagically, as described in the SPA fallback section of their documentation.

This is the set up they suggest:

{

"routes": [

{ "handle": "filesystem" },

{ "src": "/.*", "dest": "/index.html" }

]

}First handle the file system, in other words, look for the physical file if it exists. In any other case, serve index.html.

Netlify

On Netlify, this is the recommended rewrite rule:

/* /index.html 200GitHub Pages

Sadly, on GitHub Pages, we cannot configure this kind of rewriting. People have been requesting this since 2015, see issue 408 on an unofficial GitIHub repository.

One solution that is offered by a friendly commenter: symlinks! GitHub Pages allows you to use a custom 404 page, by creating a 404.html file in the root of your project. Whenever the GitHub Pages server cannot find your files and serves a 404, it will serve 404.html.

Commenter wf9a5m75 suggests a symlink:

$> cd docs/

$> ln -s index.html 404.htmlThis will serve our index.html when files are not found. Caveat: it will do this with a 404 status code, which is going to be incorrect if we genuinely have content for the path. Boohoo. It could have all sorts of side effects, including for search engine optimisation, if that’s your thing.

Another way to hack around it, is to have a meta refresh tag, as Daniel Buchner suggests over at Smashing Magazine.

Let’s hope GitHub Pages will one day add functionality like that of Vercel and Netlify.

Wrapping up

Routing was easier when we used servers to decide what to serve. Moving routing logic to the client has some advantages, but comes with problems of its own. The best way to ‘do’ a single page app, is to have a server-side fallback. so that servers can just do the serving as they have always done. Generate static files, that servers can find. Don’t make it our user’s problem that we wanted to use a fancy client-side router. Now, should we not have a fallback for our client-side routes, redirect rules can help, like the one’s Vercel and Netlify recommend. On GitHub Pages, we can hack around it.

Originally posted as How deployment services make client-side routing work on Hidde's blog.

Uncanny Valley

“It’s unfortunate that the world does not reward conciseness more. Making books shorter will effectively increase the rate at which we can learn.” This tweet from a start-up founder is quoted in Anna Wiener’s hilarious memoir Uncanny Valley, in which she tears apart the “dreary efficiency fetish” of the San Francisco tech scene, among other things. It touched me, because I love books and don’t want them disrupted.

At 25, Wiener left her life in Brooklyn, New York for San Francisco, to go work in the Valley. This book is her “memoir”. She was astounded by what she found: the constant gospel of work as the most important part of life, men who are overly confident about their own ideas, open bars, the 24 hour hustle, the dress code of company branded hoodies, God Mode, camping trips with no actual camping, childish company names, companies ran by people in their 20s, an office reception that is a replica of the Oval Office… the book is full of these on point details. Most of these phenomena were not new or shocking to me (as someone who works in tech), but I enjoyed Wiener’s liberal arts perspective on them. Her somewhat ironic tone works really well for this kind of thing, as it nicely cuts through the nonsense. I chuckled a lot. It’s not a 300 page rant, though, Wiener does not simply attack everything the Valley stands for (there are other books for that), it’s more subtle.

It also isn’t just irony and fun. Wiener also takes the time to discuss serious problems in tech, including the feeling of “not belonging”, both as a women and as a non-engineer (she worked in support, and apparently that’s lower in the hierarchy). When, for work, she attended the Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing, she describes she doesn’t feel like a women in computing, “more like a women around computers, a woman with a computer”. The “young founders” aspect, besides great to poke fun at, is also a serious problem, when tech companies hugely disrupt society. Their leaders may not have enough life experience to see the full picture, yet they feel they do, because venture capitalists put them on a pedestal.

Uncanny Valley doesn’t name names, it offers descriptions instead. A great style choice, because the descriptions say much more than the actual names would have. They add a little bit of context. The social network that everybody hated, the data analytics startup where everybody wears company-supplied “I am data driven” t-shirts, the venture capitalist who had said ‘software eats the world’, the open source code platform and the highly litigious Seatle-based conglomorate (that ends up buying that code platform). Uncanny Valley is not about the specific companies, but about the culture and the kinds of companies.

The book has a special place for Silicon Valley thought leaders and what Wiener calls the “founder realism genre”: the blog posts they publish. Men, mostly men, give each other ‘anecdote-based instruction and bullet point advice’. You know the kind of Medium post. Not all men, not all Medium posts, but you get the idea. Founders who are convinced everything needs the type of efficiency they specialise in, while shielded from the consequences of their own transformations. Founders indifferent to some of the big problems of our time: inequality strengthened by their business models, hate speech amplified by their platforms and mass surveillance enabled by their data, In an interview with Vox, Wiener says:

Silicon Valley is a culture focused on doing, not reflecting or thinking.

Reflecting is essential, and the Valley could do more of it. Wiener reflects also about herself, her life and her career choices. Wiener seems to like and understand the people she meets, truly tries to figure out what motivates them and isn’t just ranting about them. For her, it seems to be a love/hate relationship, with quite a bit of both. That makes this book so strong.

Recommended reading! If you want to learn more, see the interview with Anna Wiener at the Strand Book Store, listen to Anna Wiener at Recode/Decode or go to the book’s website.

Originally posted as Uncanny Valley on Hidde's blog.

Minimum Viable Data Collection

The gist of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is simple: protect citizens from data-hungry corporations. It gives people control over how their personal data is collected, as it requires website-owners to stick to a set of rules when dealing with people’s data (I’m paraphrasing). In short: it gives rights to citizens and duties to (digital) businesses.

Most websites in Europe have taken action to comply with parts of their duties, by implementing cookie consent banners. In the least bad scenario, the response of such website-owners was: let’s find out which cookies we set and which ones we allow others to set. Then ask users for permission and set cookies if permitted. So, basically, business as usual, but with a banner for explanation.

Of course, cookies themselves are not the problem per se. It is the broader strategy, which hardly requires cookies. It is to try and get as much information from users as possible and combining everything you can find, to create detailed profiles of website visitors. This is enabled by and helps enable surveillance capitalism, which threatens our societies and people in many ways.

What if website-owners used the logical opposite of that strategy? What if our industry championed… Minimum Viable Data Collection? This strategy would collect the minimum information from users. Maybe it would actively destroy and anonymise any personal data. You would find out what kind of tracking you do or enable (via third-parties) and reduce it. Ideally to zero. This strategy respects citizen’s rights much better.

Does this idealist blogger need more realism? Well, maybe. Let’s still explore this idea.

The current state of affairs

How do websites currently deal with their privacy-related obligations? Well, many ask permission to set cookies. Some use pointy formulations like ‘would you mind some cookies?’, completed with a picture of a cookie jar. Oatly, a company that makes vegan milk (yay!), is just of many going down this route:

“Cookies go nicely with oat drinks. As it happens, the digital kind do too. So is it okay with you if we use cookies on this site?”

“Cookies go nicely with oat drinks. As it happens, the digital kind do too. So is it okay with you if we use cookies on this site?”

These are sometimes funny and original, but, also, they indicate these companies do not see online tracking as a serious problem. That’s understandable, it’s a complex problem, maybe we can’t expect marketeers to do their homework. But isn’t this too important to be turned into a joke?

Why do websites track?

The amount of cookie banners in the wild may lead us to conclude: websites really need tracking to function. Yet they don’t. So why do websites track?

From the perspective of surveillance capitalist companies, the need for tracking is clear: their business is built upon it. Again, see Shoshana Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

What I’m interested in: why do website owners wilfully welcome bad trackers on their web properties? Surely, it would be easier to comply with data collection regulations by not collecting data at all? Minimum Viable Data Collection seems to be the most straightforward solution (Ockham’s razor!).

I think these are some of the common reasons why sites don’t focus on minimising data collection yet:

- Unaware of the harm

- Some organisations may not have read up the consequences of using whatever part of their tools come with naughty trackers. This is not a valid excuse, but it may explain a majority of cases.

- User research

- Often, website owners want to track users to inform their design decisions. Through A/B tests (which aren’t trivial to get right, or other quantitative UX research on live websites.

- Social media

- A lot of websites embed content from third-parties, like videos from YouTube. Some also include buttons that allow social sharing, like Tweet This buttons. All of these come with tracking code more often than not. It’s unclear if people actually use them (but it seems some do).

- Data collection for marketing

- Some websites, especially those in the business of sales (like hotel or flight booking sites), collect user data so that they can make better (automated) decisions on offers and pricing.

Instead of maximising consent, minimise collection

The question all website owners should be asking, is: do we really, really need these trackers to exist on our pages? Can’t we do the things we want to do without trackers?

I think in many cases we can:

- Unaware of the harm

- More awereness is needed. As people who make websites and know how tracking works, we have to tell our clients and bosses.

- User research

- Maybe prioritise qualitative research? Or urge vendors of this software to design privacy-first?

- Social media

- Social sharing buttons could just be regular links (

) with information passed via parameters. Video embeds could be activated only when clicked. - Data collection for marketing

- Maybe just don’t? If trust is good for business, dark patterns are not.

The no tracking movement

Excitingly, some websites choose to avoid or minimise tracking already.

The mission statement

Privacy and accessibility expert Laura Kalbag describes why she chose not to have trackers on her site:

For me, “no tracking” is both a fact and a mission statement. I’m not a fan of tracking. (…) That means that you will not find any analytics, article limits or cookies on my site. You also won’t find any third-party scripts, content delivery networks or third-party fonts. I won’t let anyone else track you either.

(From I don’t track you)

Laura was inspired by designer and front-end engineer Karolina Szczur, whose personal website sports ‘No tracking’ in the footer. So cool, and very thoughtful.

Dutch public broadcasters go cookie-less

I was pleasantly surprised to see STER, the department that runs advertising for Dutch public broadcasters on tv, radio and internet, decided to go cookieless for all of their web advertising in 2020. Instead of profiling users, they profile their own content. STER classifies their content into 23 “contexts” (like “sport/fitness” and “cooking/food”). They then allow advertisers to choose in which context they want to promote their brand. Cool, they can be in the advertising business, offer contextual advertising spots, without the need for tracking all the things.

NRC: “our journalism is our product”

Dutch newspaper NRC also stopped using third party cookies, and takes a clear stance:

Our journalism is our product. You are not. So we do not sell your data. Never. To nobody. We do not collect data for collection’s sake. We only save data with a tangible goal, like dealing with your subscription.

From NRC privacy (translation mine)

I like the stance, but should note my tracker blocker still has to filter 5 known trackers out when I read the news (also goes for paying users).

New York Times: less targeting, more revenue

Last year, The New York Times swapped behavioural targeting for targeting based on location and context. This did not decrease their revenue. Jean-Christophe Demarta, Senior Vice President for global advertising at the paper: “We have not been impacted from a revenue standpoint, and, on the contrary, our digital advertising business continues to grow nicely.”

Digiday editor Jessica Davies:

The publisher’s reader-revenue business model means it fiercely guards its readers’ user experience. Rather than bombard readers with consent notices or risk a clunky consent user experience, it decided to drop behavioral advertising entirely.

(Emphasis mine; both quotes from: After GDPR, The New York Times cut off ad exchanges in Europe - and kept growing ad revenue)

Again, my tracker blocker found 3 trackers when I visited nytimes.com this morning.

For large scale websites, it seems minimising data collection is easier said than done. Currently, there may not be any large sites that are truly tracker-free (besides Wikipedia).

GitHub: “Pretty simple, really”

In 2020, code platform GitHub decided to get rid of their cookie banner,by getting rid of their cookies. CEO Nat Friedman writes:

we have removed all non-essential cookies from GitHub, and visiting our website does not send any information to third-party analytics services.

(from: No cookie for you)

This fits well within their values, Friedman explains, “developers should not have to sacrifice their privacy to collaborate on GitHub.” I’d still love them to stop working with ICE.

Wrapping up

It is a concept for mostly inspirational purposes, but really… I think minimum viable data collection can be a great strategy for businesses who want to comply with the duties of privacy regulations. The advantages:

- you need to build less complex cookie consent mechanisms

- users stay on your site as they are less frustrated

- you can serve customers that use tracking protection (see below)

- your company gets hundreds of internet points

To users who need to browse today’s web, I strongly recommend using a browser with strong tracking protection, like Firefox (has Enhanced Tracking Protection) or Safari (has Intelligent Tracking Prevention. For nerds who want to read more, check out the intelligent tracking posts on the WebKit blog, including Preventing Tracking Prevention Tracking or the Firefox Tracking Protection section on MDN.

Originally posted as Minimum Viable Data Collection on Hidde's blog.