Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

2020 in review

It’s that time of the year again! In this post, I’ll share some highlights of my 2020, a year that I personally can’t wait to leave behind. Below, you’ll find what I’ve been up to and some things that I have learned.

This year I have had some great things happen to me: I became a father for the second time and moved house. It has also been a struggle in many ways. But I’ll repeat my disclaimer from 2018, in these public posts, for reasons, I chose to leave the “lowlights” out. Rest assured there were many, as I imagine was the case for you too.

Highlights

Projects

It has been a good year for my freelance practice, also a stressful one, particularly in lockdown times.

I spent the vast majority of my time this year working with the Web Accessibility Initiative at the W3C. This year, I worked on various things:

- redesign of WCAG supporting documents, like Techniques and Understanding, to launch sometime next year, with improvements including syntax highlighting and clarified context

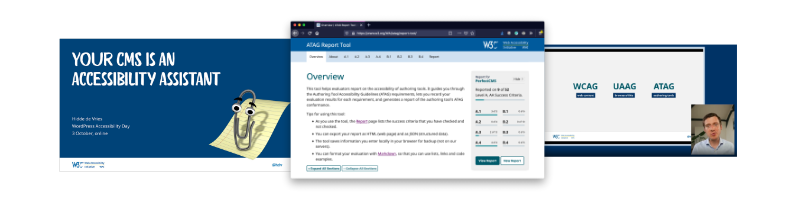

- talks about the importance of authoring tools, like Your CMS is an accessibility assistant for WordPress Accessibility Day

- launched the ATAG Report tool, which can be used to report on accessibility issues in authoring tools, like CMSes, e-learning systems and form generators

In the time that was left, I did a bunch of accessibility audits and workshops in my own capacity. Some for my own clients, some for the clients of consultancies like Firm Ground and Eleven Ways. I also had a short advisory role on the CoronaMelder website, helping with accessibility and code reviews.

I gladly said yes to all of these things, and loved combining the standards-oriented work with the practical hands-on stuff. It’s truly been good to see people understand accessibility better.

Speaking

Almost all of my speaking this year was virtual. I had planned to represent W3C/WAI at the CSUN accessibility conference this year, but this ended up the first of many events cancelled.

The only in-person talk of the year was a practice round for that CSUN talk: Amplifying your accessibility with better authoring tools. It was in Groningen, close to where I grew up and first worked, and I also got to see Maike do her awesome talk about empathy in government.

I also did some private talks, and these public talks, all online:

- Amplifying your accessibility with better authoring tools at A Future Date

- Advancing authoring tool accessibility at an AccessU event with an all-WAI line-up introducing all we’ve been working on

- On the origin of cascades by means of natural selectors, a Darwin-themed look into the evolution of CSS, at CSS Café, virtually in Boden, Germany

- 6 ways to make your site more accessible at Full Stack Utrecht

- Your CMS is an accessibility assistant at WordPress Accessibility Day

- On auto sizes in Grid Layout, about sizes in CSS. It was a dream come true to speak at Singapore CSS, an event organised by awesome humans.

- It’s the markup that matters at Vercel’s Nextjs Conf, packed with accessibility info, aimed at full stack developers.

Generally, online talks felt harder than IRL ones, because of less audience interaction and more preparation time. There was also less meeting people and traveling.

Less traveling was also an advantage: I could cook family dinner after delivering a talk, instead of being away for a few days. There was also one time where I attended my Q&A with a plaster, because I thought I could do some meal prep in a conference break. 🩹

Reading

I was able to read plenty and discovered a bunch of new authors that brought me joy and wisdom. I did one reading list post this year: Equality, a reading list (2).

If you’re looking for recommendations, find me on Goodreads (email/DM for my handle), I read in Dutch and English. These are some highlights in fiction:

- Celeste Ng’s Little fires everywhere, and also her debut Everything I never told you

- Anna Wiener’s Uncanny valley, about a woman in publishing who moves to Silicon Valley and is rightly shocked by the men, the hustle, the offices, weird camping trips… (see also my review)

- Naoise Dolan’s Exciting Times, about millennials in Hong Kong

- Johan Harstad’s Max, Mischa & Tetoffensiven, about identity, living abroad, friendship, Norway, the US and much more, blew me away. Sorry if you don’t read German, Dutch or Norwegian, it wasn’t (yet) translated to English.

These were my favourites in non-fiction:

- Jia Tolentino’s Trick Mirror, essays about the culture of the self

- Wendy Liu’s Abolish Silicon Valley, about what’s wrong with Silicon Valley’s ideology

- Michael Sandel’s The Tyranny of Merit , about why meritocracy is a lie

- Ibram X Kendi’s How to be an anti-racist – paraphrasing Dutch journalist Pete Wu: it’s probably not right to think in strict boxes but the categories of “racist” and “anti-racist” seem like a very useful distinction to make. Ibram X Kendi’s work has been my favourite about anti-racism so far. He narrates the audiobook himself and it is super powerful.

Writing

I wrote a lot less. Partly, I’ll blame 2020. Partly, it may be due to more of my work involving writing.

Some of the posts I did write:

- Could browsers fix more accessibility problems automatically and More accessible defaults, please– the web could be made more accessible from many sides: teams building website, website creation software, but also browsers. These posts go into what could be built into browsers.

- How deployment services make client-side routing work about hosting SPAs with routers

- Minimum Viable Data Collection, where I argue that if we want to follow the spirit of GDPR, we should collect data minimally, rather than beg for permission to collect maximally.

For the next year, I have some drafts floating around, that I hope to once finish and publish.

Cities

Last year, I had a “Cities” section. This section will be resumed next year.

Things I learned

I didn’t really do any side projects or volunteering this year. Some things I have learned this year:

- the basics of XSLT, which is used at W3C/WAI to generate the documents that support the WCAG standard

- I struggled a bit with git submodules, and ended up learning a bit about them

- For obvious reasons, I worked on talk recording skills and found out it’s all about light, light and light. And that I pull weird faces and should move my head less.

- Audiobooks allow one to read while going for a walk or doing the dishes, which are some of the few tasks reading can nicely be combined with.

- Static site generators are perfect for creating WCAG conformance reports. Turning HTML into an accessible PDF is not trivial, and one almost certainly requires PrinceXML for it. It doesn’t support Grid Layout, but has lots of print-specific CSS that is fun to play with, should you be a CSS nerd.

Dear readers, I hope 2021 treats you well. Hang in there.

Should you want to read more personal review posts, check out those of Michelle, Matthias, Melanie, Chee Aun, Una, Nienke, Max, Marcus and Brad.

Reply via email

2020 in review

It’s that time of the year again! In this post, I’ll share some highlights of my 2020, a year that I personally can’t wait to leave behind. Below, you’ll find what I’ve been up to and some things that I have learned.

This year I have had some great things happen to me: I became a father for the second time and moved house. It has also been a struggle in many ways. But I’ll repeat my disclaimer from 2018, in these public posts, for reasons, I chose to leave the “lowlights” out. Rest assured there were many, as I imagine was the case for you too.

Highlights

Projects

It has been a good year for my freelance practice, also a stressful one, particularly in lockdown times.

I spent the vast majority of my time this year working with the Web Accessibility Initiative at the W3C. This year, I worked on various things:

- redesign of WCAG supporting documents, like Techniques and Understanding, to launch sometime next year, with improvements including syntax highlighting and clarified context

- talks about the importance of authoring tools, like Your CMS is an accessibility assistant for WordPress Accessibility Day

- launched the ATAG Report tool, which can be used to report on accessibility issues in authoring tools, like CMSes, e-learning systems and form generators

In the time that was left, I did a bunch of accessibility audits and workshops in my own capacity. Some for my own clients, some for the clients of consultancies like Firm Ground and Eleven Ways. I also had a short advisory role on the CoronaMelder website, helping with accessibility and code reviews.

I gladly said yes to all of these things, and loved combining the standards-oriented work with the practical hands-on stuff. It’s truly been good to see people understand accessibility better.

Speaking

Almost all of my speaking this year was virtual. I had planned to represent W3C/WAI at the CSUN accessibility conference this year, but this ended up the first of many events cancelled.

The only in-person talk of the year was a practice round for that CSUN talk: Amplifying your accessibility with better authoring tools. It was in Groningen, close to where I grew up and first worked, and I also got to see Maike do her awesome talk about empathy in government.

I also did some private talks, and these public talks, all online:

- Amplifying your accessibility with better authoring tools at A Future Date

- Advancing authoring tool accessibility at an AccessU event with an all-WAI line-up introducing all we’ve been working on

- On the origin of cascades by means of natural selectors, a Darwin-themed look into the evolution of CSS, at CSS Café, virtually in Boden, Germany

- 6 ways to make your site more accessible at Full Stack Utrecht

- Your CMS is an accessibility assistant at WordPress Accessibility Day

- On auto sizes in Grid Layout, about sizes in CSS. It was a dream come true to speak at Singapore CSS, an event organised by awesome humans.

- It’s the markup that matters at Vercel’s Nextjs Conf, packed with accessibility info, aimed at full stack developers.

Generally, online talks felt harder than IRL ones, because of less audience interaction and more preparation time. There was also less meeting people and traveling.

Less traveling was also an advantage: I could cook family dinner after delivering a talk, instead of being away for a few days. There was also one time where I attended my Q&A with a plaster, because I thought I could do some meal prep in a conference break. 🩹

Reading

I was able to read plenty and discovered a bunch of new authors that brought me joy and wisdom. I did one reading list post this year: Equality, a reading list (2).

If you’re looking for recommendations, find me on Goodreads (email/DM for my handle), I read in Dutch and English. These are some highlights in fiction:

- Celeste Ng’s Little fires everywhere, and also her debut Everything I never told you

- Anna Wiener’s Uncanny valley, about a woman in publishing who moves to Silicon Valley and is rightly shocked by the men, the hustle, the offices, weird camping trips… (see also my review)

- Naoise Dolan’s Exciting Times, about millennials in Hong Kong

- Johan Harstad’s Max, Mischa & Tetoffensiven, about identity, living abroad, friendship, Norway, the US and much more, blew me away. Sorry if you don’t read German, Dutch or Norwegian, it wasn’t (yet) translated to English.

These were my favourites in non-fiction:

- Jia Tolentino’s Trick Mirror, essays about the culture of the self

- Wendy Liu’s Abolish Silicon Valley, about what’s wrong with Silicon Valley’s ideology

- Michael Sandel’s The Tyranny of Merit , about why meritocracy is a lie

- Ibram X Kendi’s How to be an anti-racist – paraphrasing Dutch journalist Pete Wu: it’s probably not right to think in strict boxes but the categories of “racist” and “anti-racist” seem like a very useful distinction to make. Ibram X Kendi’s work has been my favourite about anti-racism so far. He narrates the audiobook himself and it is super powerful.

Writing

I wrote a lot less. Partly, I’ll blame 2020. Partly, it may be due to more of my work involving writing.

Some of the posts I did write:

- Could browsers fix more accessibility problems automatically and More accessible defaults, please– the web could be made more accessible from many sides: teams building website, website creation software, but also browsers. These posts go into what could be built into browsers.

- How deployment services make client-side routing work about hosting SPAs with routers

- Minimum Viable Data Collection, where I argue that if we want to follow the spirit of GDPR, we should collect data minimally, rather than beg for permission to collect maximally.

For the next year, I have some drafts floating around, that I hope to once finish and publish.

Cities

Last year, I had a “Cities” section. This section will be resumed next year.

Things I learned

I didn’t really do any side projects or volunteering this year. Some things I have learned this year:

- the basics of XSLT, which is used at W3C/WAI to generate the documents that support the WCAG standard

- I struggled a bit with git submodules, and ended up learning a bit about them

- For obvious reasons, I worked on talk recording skills and found out it’s all about light, light and light. And that I pull weird faces and should move my head less.

- Audiobooks allow one to read while going for a walk or doing the dishes, which are some of the few tasks reading can nicely be combined with.

- Static site generators are perfect for creating WCAG conformance reports. Turning HTML into an accessible PDF is not trivial, and one almost certainly requires PrinceXML for it. It doesn’t support Grid Layout, but has lots of print-specific CSS that is fun to play with, should you be a CSS nerd.

Dear readers, I hope 2021 treats you well. Hang in there.

Should you want to read more personal review posts, check out those of Michelle, Matthias, Melanie, Chee Aun, Una, Nienke, Max, Marcus and Brad.

Originally posted as 2020 in review on Hidde's blog.

Why it's good for users that HTML, CSS and JS are separate languages

This week, somebody proposed to replace HTML, CSS and JavaScript with just one language, arguing “they heavily overlap each other”. They wrote the separation between structure, styles and interactivity is based on a “false premise“. I don’t think it is. In this post, we’ll look at why it is good for people that HTML, CSS and JS are separate languages.

I’m not here to make fun of the proposal, anyone is welcome to suggest ideas for the web platform. I do want to give an overview of why the current state of things works satisfactorily. Because, as journalist Zeynep Tefepkçi said (source):

If you have something wonderful, if you do not defend it, you will lose it.

On a sidenote: the separation between structure, style and interactivity goes all the way back to the web’s first proposal. At the start, there was only structure. The platform was for scientists to exchange documents. After the initial idea, a bunch of smart minds worked years on making the platform to what it is and what it is used for today. This still goes on. Find out more about web history in my talk On the origin of cascades (video), or Jeremy Keith and Remy Sharpe’s awesome How we built the World Wide Web in 5 days.

Some user needs

Users need structure separated out

The interesting thing about the web is that you never know who you’re building stuff for exactly. Even if you keep statistics. There are so many different users consuming web content. They all have different devices, OSes, screen sizes, default languages, assistive technologies, user preferences… Because of this huge variety, having the structure of web pages (or apps) expressed in a language that is just for structure is essential.

We need shared structure so that:

- screen reader users can navigate web pages by heading (see headings are tables of contents).

- people with an attention disorder can turn on reader mode

- people with motor impairments can use autofill (see Identify Input Purpose)

- people who want to read a foreign language page in their mother tongue can stick a URL into Google Translate

All of these users rely on us writing HTML (headings, semantic structure, autocomplete attributes, lang attributes, respectively). Would we want to break the web for those users? Or, if we use the JSON abstraction suggested in the aforementioned proposal, and generate DOM from that, would it be worth breaking the way developers are currently used to making accessible experiences? This stuff is hard to teach as it is.

Even if we would time travel back to the nineties and could invent the web from scratch, we’d still need to express semantics. Abstracting semantics to JSON may solve some problems and make some people’s life easier, but having seen some attempts to that, it usually removes the simplicity and flexibility that HTML offers.

Users need style separated out

Like it is important to have structure separated out, users also need us to have style as a separate thing.

We need style separated out, so that:

- people with low vision can use high contrast mode; a WebAIM survey showed 51.4% do (see also Melanie Richard’excellent The Tailored Web: Effectively Honoring Visual Preferences)

- people who only have a mobile device can access the same website, but on a smaller screen (responsive design worked, because CSS allowed HTML to be device-agnostic)

- people with dyslexia may want to override some styles use a dyslexia friendly typeface (see Dyslexic Fonts by Seren Davies)

- people who (can) only use their keyboard can turn on browser plugins that force focus outlines

- users of Twitter may want to use a custom style sheet to turn off the Trending panel (it me 🙄)

Users need interactivity separated out

Some users might even want (or have) interactivity separated out, for instance if the IT department of their organisation turned the feature off company-wide. Some users have JavaScript turned off manually. These days, neither are common at all, but there are still good reasons to think about what your website is without JavaScript, because JavaScript loss can happen accidentally.

We need interactivity separated out, because:

- some people use a browser with advanced tracking protection, like Safari or Firefox (see my post On the importance of testing with content blockers)

- some people may be on low bandwidth

- some people may use an old device or operating system for valid reasons

- some people may be going to your site while you’ve just deployed a script that breaks in some browsers, but you’ve not found out during testing, because it is obscure

As Jake Archibald said in 2012:

“We don’t have any non-JavaScript users” No, all your users are non-JS while they’re downloading your JS

That’s right, all your users are non-JS while they’re downloading your JS.

Existing abstractions

None of this is to say it can’t be useful to abstract some parts of the web stack, for some teams. People abstract HTML, CSS and JavaScript all the time. People happily separate concerns differently: not on a page level, but on a UI component level.

On the markup end of things, there are solutions like Sanity’s Portable Text that defines content in JSON, so that it can be reused across many different “channels”. This is a format for storing and transferring data, not for displaying it on a site. Because before you display it anywhere, you’d write a template to do that, in HTML. In a government project I worked on years ago, the team abstracted form fields to JSON before converting them to HTML. I currently work on a project where we use XSLT to specify some stuff before generating HTML.

For CSS there are extensions like Sass and Less, utility-first approaches like Tailwind and many methods to define CSS inside JavaScript component. From JSSS (from 1997) to CSS in JS today, there is lots to choose.

As for JavaScript: there are numerous abstractions that make some of the syntax of JavaScript easier (jQuery, in its time), that help developers write components with less boilerplate (like Svelte and Vue) and that help teams make less programmatically avoidable mistakes (TypeScript).

I don’t use any of these abstractions for this site, or most others I work on. Yet, many approaches are popular with teams building all sorts of websites. Choose any or no abstractions, whatever helps you serve the best HTML, CSS and JS to end users.

We’re very lucky that all of these abstract things that are themselves simple (ish) building stones: HTML, CSS and (to a different extent) JavaScript. With abstractions, individual teams and organisations can separate their concerns differently as they please, without changing the building blocks that web users rely on.

Could you benefit people in your abstractions? Maybe. The proposal mentions specific parameters for visual impairments and content that can trigger seizures. But it is better for users (including their privacy) to have such things in the main HTML and CSS, regardless of whether that was written by hand or outputted by some abstraction.

Conclusion

The separation between HTML, CSS and JavaScript as it currently is benefits web users. It does this in many ways that sometimes only become apparent after years (CSS was invented 25 years ago, when phones with browsers did not yet exist, but different media were already taken into account). It’s exciting to abstract parts of the web and remodel things for your own use case, but I can’t emphasise enough that the web is for people. Well written and well separated HTML and CSS is important to their experience of it.

Thanks to Darius, Jen, Krijn, Thijs, Tim and Coralie for pointing out typos and mishaps.

Reply via email

Why it's good for users that HTML, CSS and JS are separate languages

This week, somebody proposed to replace HTML, CSS and JavaScript with just one language, arguing “they heavily overlap each other”. They wrote the separation between structure, styles and interactivity is based on a “false premise“. I don’t think it is. In this post, we’ll look at why it is good for people that HTML, CSS and JS are separate languages.

I’m not here to make fun of the proposal, anyone is welcome to suggest ideas for the web platform. I do want to give an overview of why the current state of things works satisfactorily. Because, as journalist Zeynep Tefepkçi said (source):

If you have something wonderful, if you do not defend it, you will lose it.

On a sidenote: the separation between structure, style and interactivity goes all the way back to the web’s first proposal. At the start, there was only structure. The platform was for scientists to exchange documents. After the initial idea, a bunch of smart minds worked years on making the platform to what it is and what it is used for today. This still goes on. Find out more about web history in my talk On the origin of cascades (video), or Jeremy Keith and Remy Sharpe’s awesome How we built the World Wide Web in 5 days.

Some user needs

Users need structure separated out

The interesting thing about the web is that you never know who you’re building stuff for exactly. Even if you keep statistics. There are so many different users consuming web content. They all have different devices, OSes, screen sizes, default languages, assistive technologies, user preferences… Because of this huge variety, having the structure of web pages (or apps) expressed in a language that is just for structure is essential.

We need shared structure so that:

- screen reader users can navigate web pages by heading (see headings are tables of contents).

- people with an attention disorder can turn on reader mode

- people with motor impairments can use autofill (see Identify Input Purpose)

- people who want to read a foreign language page in their mother tongue can stick a URL into Google Translate

All of these users rely on us writing HTML (headings, semantic structure, autocomplete attributes, lang attributes, respectively). Would we want to break the web for those users? Or, if we use the JSON abstraction suggested in the aforementioned proposal, and generate DOM from that, would it be worth breaking the way developers are currently used to making accessible experiences? This stuff is hard to teach as it is.

Even if we would time travel back to the nineties and could invent the web from scratch, we’d still need to express semantics. Abstracting semantics to JSON may solve some problems and make some people’s life easier, but having seen some attempts to that, it usually removes the simplicity and flexibility that HTML offers.

Users need style separated out

Like it is important to have structure separated out, users also need us to have style as a separate thing.

We need style separated out, so that:

- people with low vision can use high contrast mode; a WebAIM survey showed 51.4% do (see also Melanie Richard’excellent The Tailored Web: Effectively Honoring Visual Preferences)

- people who only have a mobile device can access the same website, but on a smaller screen (responsive design worked, because CSS allowed HTML to be device-agnostic)

- people with dyslexia may want to override some styles use a dyslexia friendly typeface (see Dyslexic Fonts by Seren Davies)

- people who (can) only use their keyboard can turn on browser plugins that force focus outlines

- users of social media may want to use a custom style sheet to turn off the Trending panel (it me 🙄)

Users need interactivity separated out

Some users might even want (or have) interactivity separated out, for instance if the IT department of their organisation turned the feature off company-wide. Some users have JavaScript turned off manually. These days, neither are common at all, but there are still good reasons to think about what your website is without JavaScript, because JavaScript loss can happen accidentally.

We need interactivity separated out, because:

- some people use a browser with advanced tracking protection, like Safari or Firefox (see my post On the importance of testing with content blockers)

- some people may be on low bandwidth

- some people may use an old device or operating system for valid reasons

- some people may be going to your site while you’ve just deployed a script that breaks in some browsers, but you’ve not found out during testing, because it is obscure

As Jake Archibald said in 2012:

“We don’t have any non-JavaScript users” No, all your users are non-JS while they’re downloading your JS

That’s right, all your users are non-JS while they’re downloading your JS.

Existing abstractions

None of this is to say it can’t be useful to abstract some parts of the web stack, for some teams. People abstract HTML, CSS and JavaScript all the time. People happily separate concerns differently: not on a page level, but on a UI component level.

On the markup end of things, there are solutions like Sanity’s Portable Text that defines content in JSON, so that it can be reused across many different “channels”. This is a format for storing and transferring data, not for displaying it on a site. Because before you display it anywhere, you’d write a template to do that, in HTML. In a government project I worked on years ago, the team abstracted form fields to JSON before converting them to HTML. I currently work on a project where we use XSLT to specify some stuff before generating HTML.

For CSS there are extensions like Sass and Less, utility-first approaches like Tailwind and many methods to define CSS inside JavaScript component. From JSSS (from 1997) to CSS in JS today, there is lots to choose.

As for JavaScript: there are numerous abstractions that make some of the syntax of JavaScript easier (jQuery, in its time), that help developers write components with less boilerplate (like Svelte and Vue) and that help teams make less programmatically avoidable mistakes (TypeScript).

I don’t use any of these abstractions for this site, or most others I work on. Yet, many approaches are popular with teams building all sorts of websites. Choose any or no abstractions, whatever helps you serve the best HTML, CSS and JS to end users.

We’re very lucky that all of these abstract things that are themselves simple (ish) building stones: HTML, CSS and (to a different extent) JavaScript. With abstractions, individual teams and organisations can separate their concerns differently as they please, without changing the building blocks that web users rely on.

Could you benefit people in your abstractions? Maybe. The proposal mentions specific parameters for visual impairments and content that can trigger seizures. But it is better for users (including their privacy) to have such things in the main HTML and CSS, regardless of whether that was written by hand or outputted by some abstraction.

Conclusion

The separation between HTML, CSS and JavaScript as it currently is benefits web users. It does this in many ways that sometimes only become apparent after years (CSS was invented 25 years ago, when phones with browsers did not yet exist, but different media were already taken into account). It’s exciting to abstract parts of the web and remodel things for your own use case, but I can’t emphasise enough that the web is for people. Well written and well separated HTML and CSS is important to their experience of it.

Originally posted as Why it's good for users that HTML, CSS and JS are separate languages on Hidde's blog.

When there is no content between headings

For accessibility purposes, you could think of headings as a table of contents. But what if there are headings without contents?

On a web page, a heading (h1, h2, h3 etc) signposts ‘a section about X starts here’. Heading names are section names, in that sense. If, in a banana bread recipe, one heading says ‘Ingredients’, and the other says ‘Method’, expectations are set about what can be found where. Under the first heading, we’ll expect what goes into the banana bread, under the second we’ll expect some steps to follow.

The issue

Now, a problem I saw on a website recently: headings with no content. The issue wasn’t empty hx elements, it was that there was no content between these elements and the next. This can happen when the heading element was picked merely for its looks, rather than as a way to indicate that there is some content—and what kind of content.

<h1>Banana bread</h1>

<h2>It's tasty</h2>

<!-- nothing -->

<h2>It's healthy</h2>

<!-- nothing -->

<h2>It can be anyway</h2>On a site with beautiful heading styles, this could look great, but structurally it is unhelpful, because when someone navigates to one of these h2’s, they find nothing.

It could also constitute a failure of WCAG 1.3.1: Info and relationships, because you’re basically claiming a structural relationship when there isn’t one.

So, the two questions to ask for headings:

- useful description: does this clearly say what kind of content I can find underneath?

- content: is there any content available underneath?

In the example above, only the h1 meets the criterion of being something we would want to navigate to. The bits underneath are more of a list of unique selling points. Something like this would be better in this context:

<h1>Banana bread</h1>

<ul>

<li>It's tasty</li>

<li>It's healthy</li>

</ul>Note: the problem is not multiple headings as such, it’s multiple headings of the same level, that have no non heading content that they are a description for.

In summary

When you use a heading element, you set the expectation of content—always have content between headings of the same level.

Thanks to Jules Ernst, who explained this problem to me first.

Update 8 September 2020: added nuance to whether this fails 1.3.1

Reply via email