Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Some notes on using esbuild

Hello!

I’ve been writing more frontend code in the last year or two – I’ve been making a bunch of little Vue projects. (for example nginx playground, sql playground, this dns lookup tool, and a couple of others)

My general approach to frontend development has been pretty “pretend it’s 2005” – I usually

have an index.html file, a script.js file, and then I do a <script

src="script.js"> and that’s it. You can see an example of that approach here.

This has been working mostly ok for me, but sometimes I run into problems. So I wanted to talk about one of those problems, a solution I found (esbuild!), and what I needed to learn to solve the problem (some very basic facts about how npm builds work).

Some of the facts in this post might be wrong because still I don’t understand Javascript build systems that well.

problem 1: libraries that tell you to npm install them

Sometimes I see Javascript libraries that I’m interested in using, and they have installation instructions like this:

npm install vue-jcrop

and code examples to use the library that look like this:

import { Jcrop } from 'vue-jcrop';

Until last week, I found this completely mystifying – I had no idea what

import was doing and I didn’t understand how to use libraries in that way.

I still don’t totally understand but I understand a tiny bit more now and I will try to explain what I’ve learned.

problem 2: I don’t understand frontend build tools

Of course, the obvious way to solve problem 1 is to use Vue.js the “normal”

way where I install it with npm and use Vite or vue-cli-service or

whatever.

I’ve used those tools before once or twice – there’s this project generator

called vue create which will set up everything for you properly, and it

totally works.

But I stopped using those tools and went back to my old <script

src="script.js"> system because I don’t understand what those

vue-cli-service and vite are doing and I didn’t feel confident that I could

fix them when they break. So I’d rather stick to a setup that I actually

understand.

I think the reason vue-cli-service is so confusing to me is that it’s

actually doing many different things – I think it:

- compiles Vue templates

- runs Babel (??)

- does type checking for Typescript (if you’re using typescript)

- does all of the above with webpack which I will not try to explain much because I don’t understand it, I think it’s a system with a million plugins that does a million things

- probably some other things I’m forgetting or don’t even know about

If I were working on a big frontend project I’d probably use those tools whether or not I understood them because they do useful things. But I haven’t been using them.

esbuild: a simple way to resolve imports

Okay! Let’s get to the point of the post!

Recently I learned about esbuild which is a new JS build tool written in Go. I’m excited

about it because it lets me use imports in my code without using a giant build

pipeline that I don’t understand. I’m also used to the style

of command-line tools written in Go so it feels more “natural” to me than other tools written in Javascript do.

Basically esbuild can resolve all the imports and then bundle everything into 1 big file.

So let’s say I want to use vue in my library. I can get it working by doing these 4 steps:

step 1: install the library I want

npm install vue or whatever.

step 2: import it in script.js

import Vue from 'vue';

step 3: run esbuild to bundle it

$ esbuild script.js --bundle --minify --outfile=bundle.js

step 4: add a <script src='bundle.js'>;

Then I need to replace all of my script tags with just one script (<script src="bundle.js">) in my HTML, and everything should just work, right?

This all seemed very simple and I was super excited about this, but…

problem 3: it didn’t work

I was really excited about this, but when I tried it

(import Vue from 'vue'), it didn’t work! I was really baffled by this, but I was eventually able to figure it out with some help from people who understood Javascript.

(spoiler: it wasn’t esbuild’s fault!)

To understand why my import didn’t work, I needed to learn a little bit more

about how frontend packaging works. So let’s talk about that.

First, I was getting this error message in the JS console (which of course I didn’t see until the 20th time I looked at the console)

[Vue warn]: You are using the runtime-only build of Vue where the template compiler is not available. Either pre-compile the templates into render functions, or use the compiler-included build.

This was bad, because I was compiling my Vue templates at runtime, so I

definitely needed the template compiler. So I just needed to convince esbuild

to give me the version of Vue with the template compiler. But how?

frontend libraries can have many different build artifacts

Apparently frontend libraries often have many different build artifacts! For example, here are all of the different Vue build artifacts I have on my computer, excluding the minified versions:

$ ls node_modules/vue/dist | grep -v min

README.md

vue.common.dev.js

vue.common.js

vue.common.prod.js

vue.esm.browser.js

vue.esm.js

vue.js

vue.runtime.common.dev.js

vue.runtime.common.js

vue.runtime.common.prod.js

vue.runtime.esm.js

vue.runtime.js

I think the different options being expressed here are:

- dev vs prod (how verbose are the error messages?)

- runtime vs not-runtime (does it include a template compiler?)

- whatever the difference between

vue.jsvsvue.esm.jsvsvue.common.jsis (something about ES6 modules vs CommonJS???)

how the build artifact usually gets chosen: webpack or something

I think the way Vue.js usually chooses which Vue version import uses is through a config file called vue.config.ts

As far as I can tell, this usually gets processed through some code in this file that looks like this:

webpackConfig.resolve

.alias

.set(

'vue$',

options.runtimeCompiler

? 'vue/dist/vue.esm.js'

: 'vue/dist/vue.runtime.esm.js'

)

Even though I have no idea how Webpack works, this is pretty helpful! It’s

saying that if I want the runtime compiler, I need to use vue.esm.js

intead of vue.runtime.esm.js. I can do that!

what build artifact is esbuild loading?

I also double checked which version of Vue esbuild is loading using strace, because I love strace:

I made a file called blah.js that looks like this:

import Vue from 'vue';

const app = new Vue()

and saw which files it opened, like this: (you have to scroll right to see the filenames)

$ strace -e openat -f esbuild blah.js --bundle --outfile=/dev/null

openat(AT_FDCWD, "/home/bork/work/mess-with-dns/frontend/package.json", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

openat(AT_FDCWD, "/home/bork/work/mess-with-dns/frontend/blah.js", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

openat(AT_FDCWD, "/home/bork/work/mess-with-dns/frontend/node_modules/vue/package.json", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

openat(AT_FDCWD, "/home/bork/work/mess-with-dns/frontend/node_modules/vue/dist/vue.runtime.esm.js", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

It looks like it just opens package.json and vue.runtime.esm.js. package.json has this main key, which must be what’s directing esbuild to

load vue.runtime.esm.js. I guess that’s part of the ES6 modules spec or

something.

"main": "dist/vue.runtime.common.js",

importing the template compiler version of Vue fixed everything

Importing the version of Vue with the template compiler was very simple in the end, I just needed to do

import Vue from 'vue/dist/vue.esm.js'

instead of

import Vue from 'vue'

and then esbuild worked! Hooray! Now I can just put that esbuild

incantation in a bash script which is how I run all my builds for tiny projects

like this.

npm install gives you all the build artifacts

This is a simple thing but I didn’t really understand it before – it seems like npm install vue:

- the package maintainer runs

npm run buildat some point and then publishes the package to the NPM registry npm installdownloads the Vue source intonode_modules, as well as the build artifacts

I think that’s right?

npm run build can run any arbitrary program, but the convention seems to be

for it to create build artifacts that end up in node_modules/vue/dist. Maybe

the dist folder is standardized by npm somehow? I’m not sure.

not every NPM package has a dist/ directory

There’s a cool NPM package called friendly-words from Glitch. If I run

npm install friendly-words, it doesn’t have a dist/ directory.

It was explained to me that this is because this a package intended to be run on the backend, so it doesn’t package itself into a single Javascript file build artifact in the same way. Instead it just loads files from disk at runtime – this is basically what it does:

$ cat node_modules/friendly-words/index.js

const data = require('./generated/words.json');

exports.objects = data.objects;

exports.predicates = data.predicates;

exports.teams = data.teams;

exports.collections = data.collections;

people seem to prefer import over require for frontend code

Here’s what I’ve understood about import vs require so far:

- there are two ways to use

import/require, you can do a build step to collapse all the imports and put everything into one file (which is what I’m doing), or you can do the imports/requires at runtime - browsers can’t do

requireat runtime, onlyimport. This is becauserequireloads the code synchronously - there are 2 standards (CommonJS and ES6 modules), and that

requireis CommonJS andimportis ES6 modules. importseems to be a lot more restricted thanrequirein general (which is good)

I think this means that I should use import and not require in my frontend code.

it’s exciting to be able to do imports

I’m pretty excited to be able to do imports in a way that I actually almost understand for the first time. I don’t think it’s going to make that big of a difference to my projects (they’re still very small!).

I don’t understand everything

esbuild is doing, but it feels a lot more approachable and transparent than

the Webpack-based tools that I’ve used previously.

The other thing I like about esbuild is that it’s a static Go binary, so I

feel more confident that I’ll be able to get it to work in the future than with

tool written in Javascript, just because I understand the Javascript ecosystem

so poorly. And it’s super fast, which is great.

How do you tell if a problem is caused by DNS?

I was looking into problems people were having with DNS a few months ago and I noticed one common theme – a lot of people have server issues (“my server is down! or it’s slow!“), but they can’t tell if the problem is caused by DNS or not.

So here are a few tools I use to tell if a problem I’m having is caused by DNS, as well as a few DNS debuggging stories from my life.

I don’t try to interpret browser error messages

First, let’s talk briefly about browser error messages. You might think that your browser will tell you if the problem is DNS or not! And it could but mine doesn’t seem to do so in any obvious way.

On my machine, if Firefox fails to resolve DNS for a site, it gives me the error: Hmm. We’re having trouble finding that site. We can’t connect to the server at bananas.wizardzines.com.

But if the DNS succeeds and it just can’t establish a TCP connection to that service, I get the error: Unable to connect. Firefox can’t establish a connection to the server at localhost:1324

These two error messages (“we can’t connect to the server” and “firefox can’t establish a connection to the server”) are so similar that I don’t try to distinguish them – if I see any kind of “connection failure” error in the browser, I’ll immediately go the command line to investigate.

tool 1: error messages

I was complaining about browser error messages being misleading, but if you’re writing a program, there’s usually some kind of standard error message that you get for DNS errors. It often won’t say “DNS” in it, it’ll usually be something about “unknown host” or “name or service not found” or “getaddrinfo”.

For example, let’s run this Python program:

import requests

r = requests.get('http://examplezzz.com')

This gives me the error message:

socket.gaierror: [Errno -2] Name or service not known

If I write the same program in Ruby, I get this error:

Failed to open TCP connection to examplezzzzz.com:80 (getaddrinfo: Name or service not known

If I write the same program in Java, I get:

Exception in thread "main" java.net.UnknownHostException: examplezzzz.com

In Node, I get:

Error: getaddrinfo ENOTFOUND examplezzzz.com

These error messages aren’t quite as uniform as I thought they would be, there are quite a few different error messages in different languages for exact the same problem, and it depends on the library you’re using too. But if you Google the error you can find out if it means “resolving DNS failed” or not.

tool 2: use dig to make sure it’s a DNS problem

For example, the other day I was setting up a new subdomain, let’s say it was https://bananas.wizardzines.com.

I set up my DNS, but when I went to the site in Firefox, it wasn’t working. So

I ran dig to check whether the DNS was resolving for that domain, like this:

$ dig bananas.wizardzines.com

(empty response)

I didn’t get a response, which is a failure. A success looks like this:

$ dig wizardzines.com

wizardzines.com. 283 IN A 172.64.80.1

Even if my programming language gives me a clear DNS error, I like to use dig

to independently confirm because there are still a lot of different error

messages and I find them confusing.

tool 3: check against more than one DNS server

There are LOTS of DNS servers, and they often don’t have the same information. So when I’m investigating a potential DNS issue, I like to query more than one server.

For example, if it’s a site on the public internet I’ll both use my local DNS

server (dig domain.com) and a big public DNS server like 1.1.1.1 or 8.8.8.8

or 9.9.9.9 (dig @8.8.8.8 domain.com).

The other day, I’d set up a new domain, let’s say it was https://bananas.wizardzines.com.

Here’s what I did:

- go to https://bananas.wizardzines.com in a browser (spoiler: huge mistake!)

- go to my DNS provider and set up bananas.wizardzines.com

- try to go to https://bananas.wizardzines.com in my browser. It fails! Oh no!

I wasn’t sure why it failed, so I checked against 2 different DNS servers:

$ dig bananas.wizardzines.com

$ dig @8.8.8.8 bananas.wizardzines.com

feedback.wizardzines.com. 300 IN A 172.67.209.237

feedback.wizardzines.com. 300 IN A 104.21.85.200

From this I could see that 8.8.8.8 actually did have DNS records for my

domain, and it was just my local DNS server that didn’t.

This was because I’d gone to https://bananas.wizardzines.com in my browser before I’d created the DNS record (huge mistake!), and then my ISP’s DNS server cached the absence of a DNS record, so it was returning an empty response until the negative cached expired.

I googled “negative cache time” and found a Stack Overflow post explaining

where I could find the negative cache TTL (by running dig SOA

wizardzines.com). It turned out the TTL was 3600 seconds or 1 hour, so I just

needed to wait an hour for my ISP to update its cache.

tool 4: spy on the DNS requests being made with tcpdump

Another of my favourite things to do is spy on the DNS requests being made and check if they’re failing. There are at least 3 ways to do this:

- Use tcpdump (

sudo tcpdump -i any port 53) - Use wireshark

- Use a command line tool I wrote called dnspeep, which is like tcpdump but just for DNS queries and with friendlier output

I’m going to give you 2 examples of DNS problems I diagnosed by

looking at the DNS requests being made with tcpdump.

problem: the case of the slow websites

One day five years ago, my internet was slow. Really slow, it was taking 10+

seconds to get to websites. I thought “hmm, maybe it’s DNS!”, so started

tcpdump and then opened one of the slow sites in my browser.

Here’s what I saw in tcpdump:

$ sudo tcpdump -n -i any port 53

12:05:01.125021 wlp3s0 Out IP 192.168.1.181.56164 > 192.168.1.1.53: 11760+ [1au] A? ask.metafilter.com. (59)

12:05:06.191382 wlp3s0 Out IP 192.168.1.181.56164 > 192.168.1.1.53: 11760+ [1au] A? ask.metafilter.com. (59)

12:05:11.145056 wlp3s0 Out IP 192.168.1.181.56164 > 192.168.1.1.53: 11760+ [1au] A? ask.metafilter.com. (59)

12:05:11.746358 wlp3s0 In IP 192.168.1.1.53 > 192.168.1.181.56164: 11760 2/0/1 CNAME metafilter.com., A 54.244.168.112 (91)

The first 3 lines are DNS requests, and they’re separated by 5 seconds. Basically this is my browser timing out its DNS queries and retrying them.

Finally, on the 3rd query, a response comes back.

I don’t actually know exactly why this happened, but I restarted my router and the problem went away. Hooray!

(by the way the reason I know that this is the tcpdump output I got 5 years ago is that I wrote about it in my zine on tcpdump, you can read that zine for free!)

problem: the case of the nginx failure

Earlier this year, I was using https://fly.io to set up a website, and I was having trouble getting nginx to redirect to my site – all the requests were failing.

I eventually got SSH access to the server and ran tcpdump and here’s what I saw:

$ tcpdump -i any port 53

17:16:04.216161 IP6 fly-local-6pn.55356 > fdaa::3.53: 46219+ A? myservice.internal. (42)

17:16:04.216197 IP6 fly-local-6pn.55356 > fdaa::3.53: 11993+ AAAA? myservice.internal. (42)

17:16:04.216946 IP6 fdaa::3.53 > fly-local-6pn.55356: 46219 NXDomain- 0/0/0 (42)

17:16:04.217063 IP6 fly-local-6pn.43938 > fdaa::3.53: 32351+ PTR? 3.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.a.a.d.f.ip6.arpa. (90)

17:16:04.218378 IP6 fdaa::3.53 > fly-local-6pn.55356: 11993- 1/0/0 AAAA fdaa:0:bff:a7b:aa2:d426:1ab:2 (70)

17:16:04.461646 IP6 fdaa::3.53 > fly-local-6pn.43938: 32351 NXDomain 0/1/0 (154)

This is a bit confusing to read, but basically:

- nginx requests an A record

- nginx requests an AAAA record

- the DNS server returns an

NXDOMAINreply for the A record - the DNS server returns a successful reply for the AAAA record, with an IPv6 address

The NXDOMAIN reponse made nginx think that that domain didn’t exist, so it

ignored the IPv6 address it got later.

This was happening because there was a bug in the DNS server – according to the DNS spec it should have been

returning NOERROR instead of NXDOMAIN for the A record. I reported the bug

and they fixed it right away.

I think it would have been literally impossible for me to guess what was

happening here without using tcpdump to see what queries nginx was making.

if there are no DNS failures, it can still be a DNS problem

I originally wrote “if you can see the DNS requests, and there are no timeouts or failures, the problem isn’t DNS”. But someone on Twitter pointed out that this isn’t true!

One way you can have a DNS problem even without DNS failures is if your program is doing its own DNS caching. Here’s how that can go wrong:

- Your program makes a DNS request and caches the result

- 6 days pass

- Your program never updates its IP address

- The IP address for the site changes

- You start getting errors

This is a DNS problem (your program should be requesting DNS updates more often!) but you have to diagnose it by noticing that there are missing DNS queries. This one is very tricky and the error messages you’ll get won’t look like they have anything to do with DNS.

that’s all for now

This definitely isn’t a complete list of ways to tell if it’s DNS or not, but I hope it helps!

I’d love to hear methods of checking “is it DNS?” that I missed – I’m pretty sure I’ve missed at least one important method.

How to get useful answers to your questions

5 years ago I wrote a post called how to ask good questions. I still really like that post, but it’s missing a few of the tactics I use to get useful answers like “interrupt people when they’re going off on an irrelevant tangent”.

what can go wrong when asking questions

Often when I ask a vague or underspecified question, what happens is one of:

- the person starts by explaining a bunch of stuff I already know

- the person explains some things which I don’t know, but which I don’t think are relevant to my problem

- the person starts giving a relevant explanation, but using terminology that I don’t understand, so I still end up being confused

None of these give me the answer to my question and this can be quite frustrating (it often feels condescending when someone embarks on a lengthy explanation of things I already know, even if they had no way of knowing that I already know those things), so let’s talk about I try to avoid situations like this and get the answers I need.

Before we talk about interrupting, I want to talk about my 2 favourite question-asking tactics again – asking yes/no questions and stating your understanding.

ask yes/no questions

My favourite tactic is to ask a yes/no question. What I love about this is that there’s a much lower chance that the person answering will go off on an irrelevant tangent – they’ll almost always say something useful to me.

I find that it’s often possible to come up with yes/no questions even when discussing a complicated topic. For example, here are a bunch of yes/no questions I asked a friend when trying to learn a little bit about databases from them:

- how often do you expect db failovers to happen? like every week?

- do you need to scale up by hand?

- are fb/dropbox both using mysql?

- does fb have some kind of custom proprietary mysql management software?

- is this because mysql and postgres were designed at a time when people didn’t think failover was something you’d have to do that frequently?

- i still don’t really understand that blog post about replsets, like is he saying that mongodb replication is easier to set up than mysql replication?

- is orchestrator a proxy?

- is the goal of the replicas you’re talking about to be read replicas for performance?

- do you route queries to a shard based on the id you’re searching for?

- is the point that with compression it takes extra time to read but it doesn’t matter because you almost never read?

The answers to yes/no questions usually aren’t just “yes” or “no” – for all of those questions my friend elaborated on the answer, and the elaborations were always useful to me.

You’ll notice that some of those questions are “check my understanding” questions – like “do you route queries to a shard based on the id you’re searching for?” was my previous understanding of how database sharding worked, and I wanted to check if it was correct or not.

I also find that yes/no questions get me answers faster because they’re relatively easy to answer quickly.

state your current understanding

My second favourite tactic is to state my understanding of how the system works.

Here’s an example from the “asking good questions” post of a “state your understanding” email I sent to the rkt-dev mailing list:

I’ve been trying to understand why the tree store / image store are designed the way they are in rkt.

My current understanding of how Docker’s image storage on disk works right now (from https://docs.docker.com/engine/userguide/storagedriver/imagesandcontainers/) is:

- every layer gets one directory, which is basically that layer’s filesystem

- at runtime, they all get stacked (via whatever CoW filesystem you’re using)

- every time you do IO, you go through the stack of directories (or however these overlay drivers work)

my current understanding of rkt’s image storage on disk is: (from the “image lifecycle” section here: https://github.com/coreos/rkt/blob/master/Documentation/devel/architecture.md)

- every layer gets an image in the image store

- when you run an ACI file, all the images that that ACI depends on get unpacked and copied into a single directory (in the tree store)

guess at why rkt decided to architect its storage differently from Docker:

- having very deep overlay filesystems can be expensive

- so if you have a lot of layers, copying them all into a directory (the “tree store”) results in better performance

So rkt is trading more space used on disk (every image in the image store gets copied at least once) for better runtime performance (there are no deep chains of overlays)

Is this right? Have I misunderstood what rkt does (or what Docker does?) Are there other reasons for the difference?

This:

- states my goal (understand rkt’s design choices)

- states my understanding of how rkt and docker work

- makes some guesses at the goal so that people can confirm/deny

This question got a great reply, which among other things pointed out something

that I’d totally missed – that the ACI format is a DAG instead of a linked

list, which I think means that you could install Debian packages in any order

and not have to rebuild everything if you remove an apt-get install in the

middle of your Dockerfile.

I also find the process of writing down my understanding is really helpful by itself just to clarify my own thoughts – sometimes by the time I’m done I’ve answered my own question :)

Stating your understanding is a kind of yes/no question – “this is my understanding of how X works, is that right or wrong?”. Often the answer is going to be “right in some ways and wrong in others”, but even so it makes the job of the answerer a lot easier.

Okay! Now let’s talk about interrupting a little bit.

be willing to interrupt

If someone goes off on a very long explanation that isn’t helping me at all, I think it’s important to interrupt them. This can feel rude, but ultimately it’s more efficient for everyone – it’s a waste of both their time and my time to continue.

Usually I’ll interrupt by asking a more specific question, because usually if someone has gone off on a long irrelevant explanation it’s because I asked an overly vague question to start with.

don’t accept responses that don’t answer your question

If someone finishes a statement that doesn’t answer you question, it’s important not to leave it there! Keep asking questions!

a couple of ways you can do this:

- ask a much more specific question (like a yes/no question) that’s in the direction of what you actually wanted to know

- ask them to clarify some terminology you didn’t understand (what’s an X?)

take a minute to think

Sometimes when asking someone a question, they’ll tell me new information that’s really surprising. For example, I recently learned that Javascript async/await isn’t implemented with coroutines (I thought it was because AFAIK Python async/await is implemented with coroutines).

I was pretty surprised by this, and I really needed to stop and think about what the implications of that were and what other questions I had about how Javascript works based on that new piece of information.

If this happens in a real-time conversation sometimes I’ll literally say something like “wait, that’s surprising to me, let me think for a minute” and try to incorporate the new data and come up with another question.

it takes a little bit of confidence

All of these things – being willing to interrupt, not accepting responses that don’t answer your questions, and asking for a minute to think – require a little bit of confidence!

In the past when I’ve struggled with confidence, I’ve sometimes thought “oh, this explanation is probably really good, I’m just not smart enough to understand it”, and kind of accepted it. And even today I sometimes find it hard to keep asking questions when someone says a lot of words I don’t understand.

It helps me to remember that:

- people usually want to help (even if their first explanation was full of confusing jargon)

- if I can get even 1 useful piece of information by the end of the conversation, it’s a victory (like the answer to a yes/no question that I previously didn’t know the answer to)

One of the reasons I dislike a lot of “how to ask questions” advice out there is that it actually tries to undermine the reader’s confidence – the assumption is that the people answering the questions are Super Smart Perfect People and you’re probably wasting their time with your dumb questions. But in reality (at least when at work) your coworkers answering the questions are probably smart well-meaning people who want to help but aren’t always able to answer questions very clearly, so you need to ask follow up questions to get answers.

how to give useful answers

There’s also a lot you can do to try not to be the person who goes off on a long explanation that doesn’t help the person you’re talking to at all.

I wrote about this already in how to answer question in a helpful way, but the main thing I do is pause periodically and check in. I’ll often say something like “does that make sense?“. (though this doesn’t always work, sometimes people will say “yes” even if they’re confused)

It’s especially important to check in if:

- You haven’t explained a concept before (because your initial explanation will probably not be very good)

- You don’t know the person you’re talking to very well (because you’ll probably make incorrect assumptions about what they know / don’t know)

being good at extracting information is a superpower

Some developers know a lot but aren’t very good at explaining what they know. I’m not trying to make a value judgement about that here (different people have different strengths! explaining things is extremely hard to do well!).

I’ve found that instead of being mad that some people aren’t great at explaining things, it’s more effective for me to get better at asking questions that will get me the answers I need.

This really expands the set of people I can learn from – instead of finding someone who can easily give a clear explanation, I just need to find someone who has the information I want and then ask them specific questions until I’ve learned what I want to know. And I’ve found that most people really do want to be helpful, so they’re very happy to answer questions.

And if you get good at asking questions, you can often find a set of questions that will get you the answers you want pretty quickly, so it’s a good use of everyone’s time!

Tools to explore BGP

Yesterday there was a big Facebook outage caused by BGP. I’ve been vaguely interested in learning more about BGP for a long time, so I was reading a couple of articles.

I got frustrated because none of the articles showed me how I could actually look up information related to BGP on my computer, so I wrote a tweet asking for tools.

I got a bunch of useful replies as always, so this blog post shows some tools you can use to look up BGP information. There might be an above average number of things wrong in this post because I don’t understand BGP that well.

I can’t publish BGP routes

One of the reasons I’ve never learned much about BGP is – as far as I know, I don’t have access to publish BGP routes on the internet.

With most networking protocols, you can pretty trivially get access to implement the protocol yourself if you want. For example you can:

- issue your own TLS certificates

- write your own HTTP server

- write your own TCP implementation

- write your own authoritative DNS server for your domain (I’m trying to do that right now for a small project)

- set up your own certificate authority

But with BGP, I think that unless you own your own ASN, you can’t publish routes yourself! (you could implement BGP on your home network, but that feels a bit boring to me, when I experiment with things I like them to actually be on the real internet).

Anyway, even though I can’t experiment with it, I still think it’s super interesting because I love networking, so I’m going to show you some tools I found to learn about BGP :)

First let’s talk through some BGP terminology though. I’m going to go pretty fast because I’m more interested in the tools and there are a lot of high level explanations of BGP out there (like this cloudflare post).

What’s an AS (“autonomous system”)

The first thing we need to understand is an AS. Every AS:

- is owned by an organization (usually a large organization like your ISP, a government, a university, Facebook, etc)

- controls a specific set of IP addresses (for example my ISP’s AS includes 247,808 IP addresses)

- has a number (like 1403)

Here are some observations I made about ASes just by doing some experimentation:

- Some fairly big tech companies don’t have their own AS. For example, I looked up Patreon on BGPView, and as far as I can tell they don’t own as AS – their main site (patreon.com, 104.16.6.49) is in Cloudflare’s AS.

- An AS can include IPs in many countries. Facebook’s AS (AS32934) definitely has IP addresses in Singapore, Canada, Nigeria, Kenya, the US, and more countries.

- It seems like IP address can be in more than one AS. For example, if I look up 209.216.230.240, it has 2 ASNs associated with it – AS6130 and AS21581. Apparently when this happens the more specific route takes priority – so packets to that IP would get routed to AS21581.

what’s a BGP route?

There are a lot of routers on the internet. For example, my ISP has routers.

When I send my ISP a packet (for example by running ping 129.134.30.0), my ISP’s routers

needs to figure out how to actually get my packet to the IP address

129.134.30.0.

The way the router figures this out is that it has a route table – it has a list

of a bunch of IP ranges (like 129.134.30.0/23), and routes it knows about to

get to that subnet.

Here’s an example of a real route for 129.134.30.0/23: (one of Facebook’s subnets). This one isn’t from my ISP.

11670 32934

206.108.35.2 from 206.108.35.254 (206.108.35.254)

Origin IGP, metric 0, valid, external

Community: 3856:55000

Last update: Mon Oct 4 21:17:33 2021

I think that this is saying that one path to 129.134.30.0 is through the

machine 206.108.35.2, which is on its local network. So the router might send

my ping packet to 206.108.35.2 next, and then 206.108.35.2 will know how to

get it to Facebook. The two numbers at the beginning (11670 32934) are ASNs.

what’s BGP?

My understanding of BGP is very shaky, but it’s a protocol that companies use to advertise BGP routes.

What happened yesterday with Facebook is that they basically made BGP announcements withdrawing all their BGP routes, so every router in the world deleted all of its routes related to Facebook, so no traffic could get there.

Okay, now that we’ve covered some basic terminology, let’s talk about tools you can use to look at autonomous systems and BGP!

tool 1: look at your ISP’s AS with BGPView

To make this AS thing less abstract, let’s use a tool called BGPView to look at a real AS.

My ISP (EBOX) owns AS 1403. Here are the IP addresses my ISP owns. If I look up my

computer’s public IPv4 address, I can check that it’s one of the IP addresses

my ISP owns – it’s in the 104.163.128.0/17 block.

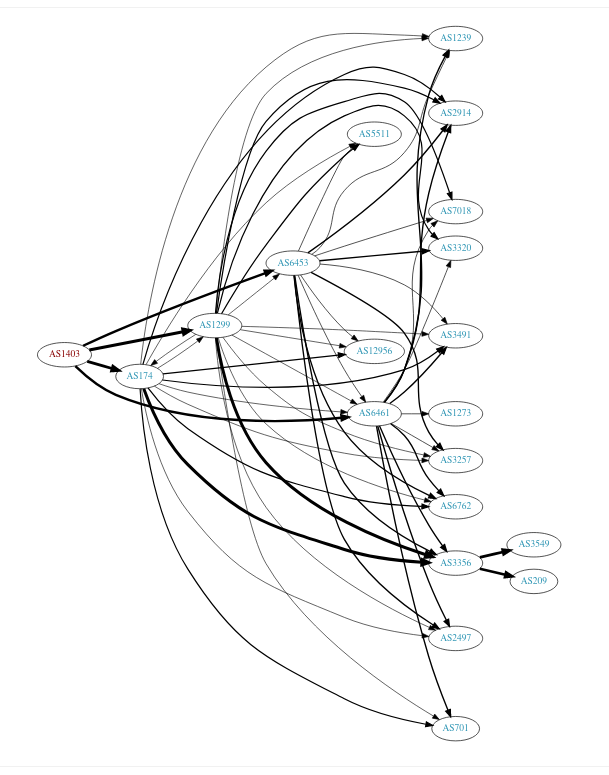

BGPView also has this graph of how my ISP is connected to other ASes

tool 2: traceroute -A and mtr -z

Okay, so we’re interested in autonomous systems. Let’s see which ASes I go through from

traceroute and mtr both have options to tell you the ASN for every IP you go through. The flags are traceroute -A and mtr -z, respectively.

Let’s see which autonomous systems I go through on my way to facebook.com with mtr!

$ mtr -z facebook.com

1. AS??? LEDE.lan

2. AS1403 104-163-190-1.qc.cable.ebox.net

3. AS??? 10.170.192.58

4. AS1403 0.et-5-2-0.er1.mtl7.yul.ebox.ca

5. AS1403 0.ae17.er2.mtl3.yul.ebox.ca

6. AS1403 0.ae0.er1.151fw.yyz.ebox.ca

7. AS??? facebook-a.ip4.torontointernetxchange.net

8. AS32934 po103.psw01.yyz1.tfbnw.net

9. AS32934 157.240.38.75

10. AS32934 edge-star-mini-shv-01-yyz1.facebook.com

This is interesting – it looks like we go directly from my ISP’s AS (1403) to Facebook’s AS (32934), with an “internet exchange” in between.

I’m not sure what an internet exchange is but I know that it’s an extremely important part of the internet. That’s going to be for another day though. My best guess is that it’s the part of the internet that enables “peering” – like an IX is a server room with a gigantic switch with infinite bandwith in it where a bunch of different companies put their computers so they can send each other packets.

mtr looks up ASNs with DNS

I got curious about how mtr looks up ASNs, so I used strace. I saw that it looked like it was using DNS, so I ran dnspeep, and voila!

$ sudo dnspeep

...

TXT 1.190.163.104.origin.asn.cymru.com 192.168.1.1 TXT: 1403 | 104.163.176.0/20 | CA | arin | 2014-08-14, TXT: 1403 | 104.163.160.0/19 | CA | arin | 2014-08-14, TXT: 1403 | 104.163.128.0/17 | CA | arin | 2014-08-14

...

So it looks like we can find the ASN for 104.163.190.1 by looking up the txt record on 1.190.163.104.origin.asn.cymru.com, like this:

$ dig txt 1.190.163.104.origin.asn.cymru.com

1.190.163.104.origin.asn.cymru.com. 13911 IN TXT "1403 | 104.163.160.0/19 | CA | arin | 2014-08-14"

1.190.163.104.origin.asn.cymru.com. 13911 IN TXT "1403 | 104.163.128.0/17 | CA | arin | 2014-08-14"

1.190.163.104.origin.asn.cymru.com. 13911 IN TXT "1403 | 104.163.176.0/20 | CA | arin | 2014-08-14"

That’s cool! Let’s keep moving though.

tool 3: the packet clearing house looking glass

PCH (“packet clearing house”) is the organization that runs a lot of internet exchange points. A “looking glass” seems to be a generic term for a web form that lets you run network commands from another person’s computer. There are looking glasses that don’t support BGP, but I’m just interested in ones that show you information about BGP routes.

Here’s the PCH looking glass: https://www.pch.net/tools/looking_glass/.

In the web form on that site, I picked the Toronto IX (“TORIX”), since that’s what mtr said I was using to go to facebook.com.

thing 1: “show ip bgp summary”

Here’s the output. I’ve redacted some of it:

IPv4 Unicast Summary:

BGP router identifier 74.80.118.4, local AS number 3856 vrf-id 0

BGP table version 33061919

RIB entries 513241, using 90 MiB of memory

Peers 147, using 3003 KiB of memory

Peer groups 8, using 512 bytes of memory

Neighbor V AS MsgRcvd MsgSent TblVer InQ OutQ Up/Down State/PfxRcd

...

206.108.34.248 4 1403 484672 466938 0 0 0 05w3d03h 50

...

206.108.35.2 4 32934 482088 466714 0 0 0 01w6d07h 38

206.108.35.3 4 32934 482019 466475 0 0 0 01w0d06h 38

...

Total number of neighbors 147

My understanding of what this is saying is that the Toronto Internet Exchange (“TORIX”) is directly connected to both my ISP (EBOX, AS 1403) and Facebook (AS 32934).

thing 2: “show ip bgp 129.134.30.0”

Here’s the output of picking “show ip bgp” for 129.134.30.0 (one of Facebook’s IP addresses):

BGP routing table entry for 129.134.30.0/23

Paths: (4 available, best #4, table default)

Advertised to non peer-group peers:

206.220.231.55

11670 32934

206.108.35.2 from 206.108.35.254 (206.108.35.254)

Origin IGP, metric 0, valid, external

Community: 3856:55000

Last update: Mon Oct 4 21:17:33 2021

11670 32934

206.108.35.2 from 206.108.35.253 (206.108.35.253)

Origin IGP, metric 0, valid, external

Community: 3856:55000

Last update: Mon Oct 4 21:17:31 2021

32934

206.108.35.3 from 206.108.35.3 (157.240.58.225)

Origin IGP, metric 0, valid, external, multipath

Community: 3856:55000

Last update: Mon Oct 4 21:17:27 2021

32934

206.108.35.2 from 206.108.35.2 (157.240.58.182)

Origin IGP, metric 0, valid, external, multipath, best (Older Path)

Community: 3856:55000

Last update: Mon Oct 4 21:17:27 2021

This seems to be saying that there are 4 routes to Facebook from that internet exchange.

the quebec internet exchange doesn’t seem to know anything about Facebook

I also tried the same thing from the Quebec internet exchange QIX (which is

presumably closer to me, since I live in Montreal and not Toronto). But the QIX

doesn’t seem to know anything about Facebook – when I put in 129.134.30.0 it

just says “% Network not in table”.

So I guess that’s why I was sent through the Toronto IX and not the Quebec one.

more BGP looking glasses

Here are some more websites with looking glasses that will give you similar

information from other points of view. They all seem to support the same show ip bgp syntax, maybe because they’re running the same software? I’m not sure.

- http://www.routeviews.org/routeviews/index.php/collectors/

- http://www.routeservers.org/

- https://lg.he.net/

There seem to be a LOT of these looking glass services out there, way more than just those 3 lists.

Here’s an example session with one of the servers on this list: route-views.routeviews.org. This time I connected via telnet and not through a web form, but the output looks like it’s in the same format.

$ telnet route-views.routeviews.org

route-views>show ip bgp 31.13.80.36

BGP routing table entry for 31.13.80.0/24, version 1053404087

Paths: (23 available, best #2, table default)

Not advertised to any peer

Refresh Epoch 1

3267 1299 32934

194.85.40.15 from 194.85.40.15 (185.141.126.1)

Origin IGP, metric 0, localpref 100, valid, external

path 7FE0C3340190 RPKI State valid

rx pathid: 0, tx pathid: 0

Refresh Epoch 1

6939 32934

64.71.137.241 from 64.71.137.241 (216.218.252.164)

Origin IGP, localpref 100, valid, external, best

path 7FE135DB6500 RPKI State valid

rx pathid: 0, tx pathid: 0x0

Refresh Epoch 1

701 174 32934

137.39.3.55 from 137.39.3.55 (137.39.3.55)

Origin IGP, localpref 100, valid, external

path 7FE1604D3AF0 RPKI State valid

rx pathid: 0, tx pathid: 0

Refresh Epoch 1

20912 3257 1299 32934

212.66.96.126 from 212.66.96.126 (212.66.96.126)

Origin IGP, localpref 100, valid, external

Community: 3257:8095 3257:30622 3257:50001 3257:53900 3257:53904 20912:65004

path 7FE1195AF140 RPKI State valid

rx pathid: 0, tx pathid: 0

Refresh Epoch 1

7660 2516 1299 32934

203.181.248.168 from 203.181.248.168 (203.181.248.168)

Origin IGP, localpref 100, valid, external

Community: 2516:1030 7660:9001

path 7FE0D195E7D0 RPKI State valid

rx pathid: 0, tx pathid: 0

Here there are a few options for routes:

3267 1299 329346939 32934701 174 3293420912 3257 1299 329347660 2516 1299 32934

I think the reason there’s more than one AS in all of these is that 31.13.80.36 is a Facebook IP address in

Toronto, so this server (which is maybe on the US west coast, I’m not sure) is

not able to connect to it directly, it needs to go to another AS first. So all of the routes have one or more ASNs

The shortest one is 6939 (“Hurricane Electric”), which is a “global internet backbone”. They also have their own hurricane electric looking glass page.

tool 4: BGPlay

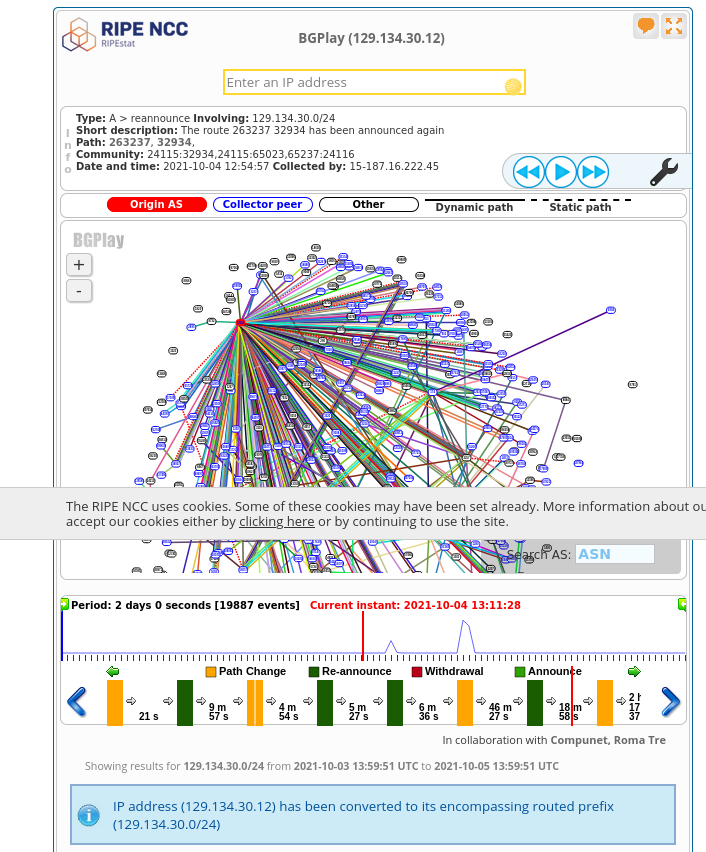

All the other tools so far have just shown us the current state of Facebook routing where everything is fine, but this 4th tool lets us see the history of this Facebook BGP internet disaster! It’s a GUI tool so I’m going to include a bunch of screenshots.

The tool is at https://stat.ripe.net/special/bgplay. I typed in the IP address 129.134.30.12 (one of Facebook’s IPs), if you want to play along.

First, let’s look at the state of things before everything went wrong. I clicked in the timeline at 13:11:28 on Oct. 4, and got this:

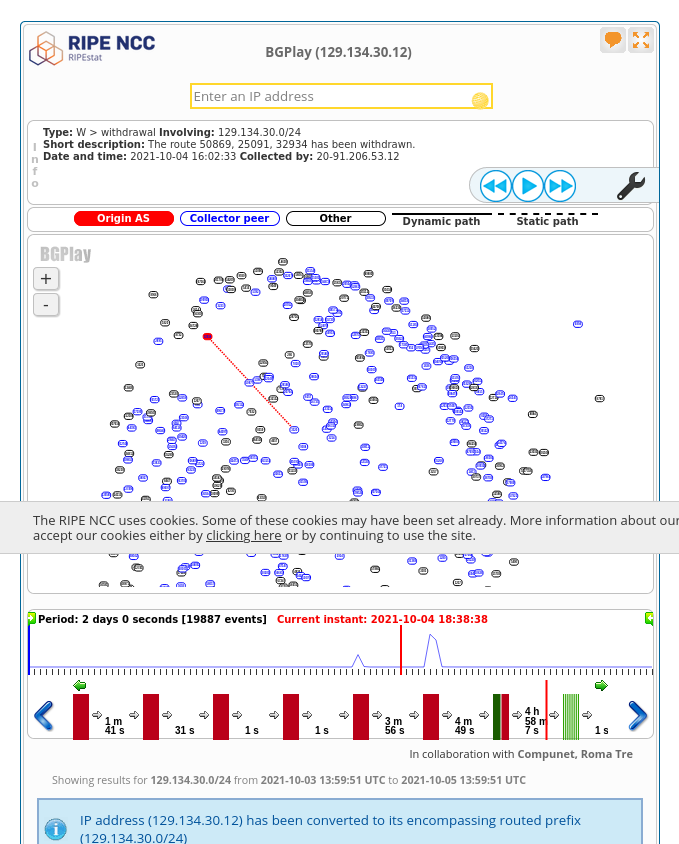

I originally found this very overwhelming. What’s happening? But then someone on Twitter pointed out that the next place to look is to click on the timeline right after the Facebook disaster happened (at 18:38 on Oct. 4).

It’s pretty clear that something is wrong in this picture – all the BGP routes are gone! oh no!

The text at the top shows the last Facebook BGP route disappearing:

Type: W > withdrawal Involving: 129.134.30.0/24

Short description: The route 50869, 25091, 32934 has been withdrawn.

Date and time: 2021-10-04 16:02:33 Collected by: 20-91.206.53.12

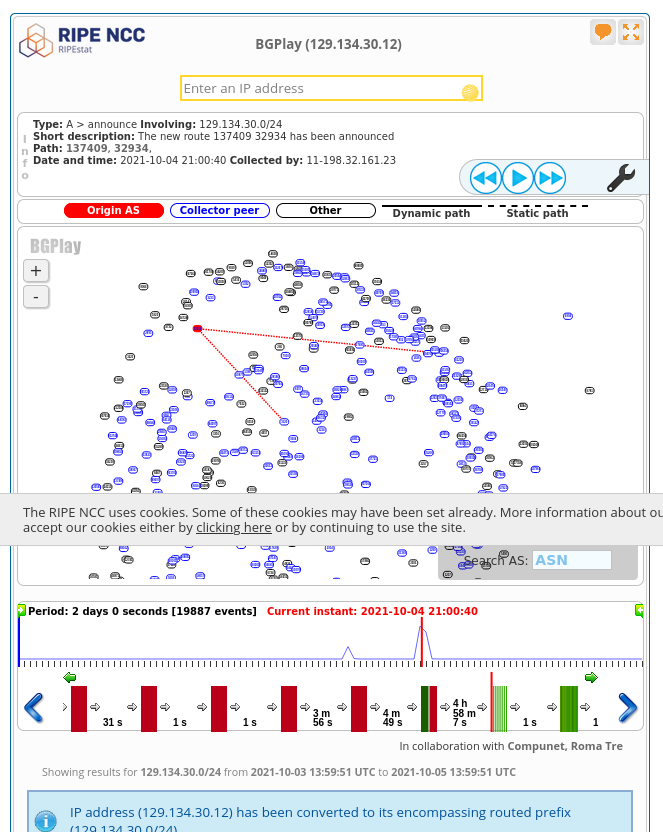

If I then click the “fast forward” button, we see the BGP routes start to come back:

The first one announced is 137409 32934. I don’t think this is actually the

first one announced though – there are a lot of route announcements inside the

same second (at 2021-10-04 21:00:40), and I think the ordering inside BGPlay is arbitrary.

If I click the “fast forward” button again, more and more routes start to come back and routing starts to go back to normal

I found looking at this outage in BGPlay really fun, even though the interface is pretty confusing at first.

maybe it is important to understand a little about BGP?

I started out this post by saying you can’t change BGP routes BGP, but then I remembered that in 2016 or 2017 there was a Telia routing issue that caused us some minor network at work. And when that happens, it is actually useful to understand why your customers can’t reach your site, even if it’s totally out of your control. I didn’t know about any of these tools at that time but I would have liked to!

I think for most companies all you can do to respond to outages caused by someone else’s bad BGP routes is “do nothing and wait for it to get fixed”, but it’s nice to be able to confidently do nothing.

some ways to publish BGP routes

If you want to (as a hobbyist) actually publish BGP routes, here are some links from the comments:

- a guide to getting your own ASN

- dn42 seems to have a playground for BGP (it’s not on the public internet, but it does have other people on it which seems more fun than just doing BGP by yourself at home)

that’s all for now

I think there are a lot more BGP tools (like PCH has a bunch of daily snapshots of routing data which look like fun), but this post is already pretty long and there are other things I need to do today.

I was surprised by how much information I could get about BGP just as a regular person, I always think of it as a “secret network wizard” thing but apparently there are all kind of public machines anybody can just telnet to and use to look at the route tables! Who knew!

All my zines are now available in print!

Hello! In June I announced that I was releasing 4 zines in print and promised “more zines coming soon”. “Soon” has arrived! You can get any zine you want in print now!

I’m doing this now so that you can get zines in the mail in time for Christmas, or any other end-of-year holiday you celebrate :)

you can preorder zines today!

First the basic facts!

- you can preorder zines as of today

- the preorder deadline is October 12

- zines will ship around November 5

- you’ll get them in time for Christmas

- more logistical details in the Preorders FAQ

Here’s the link to get them:

Here are a few more notes about how the print zines work – they’re mostly the same as last time

why a preorder?

It makes it easier to decide how many zines to print! I don’t want to accidentally underestimate demand and then not have enough zines for everyone who wants them. With a preorder, everyone can get all the zines they want!

great print quality!

I’m working with the same wonderful print company again to print the zines (Girlie Press). I don’t have photos of the new zines yet, but here are some photos from people who received the last batch of zines:

(these are all Twitter embeds so they probably won’t work if you’re reading this an email / RSS feed)

I got by mail these beautiful zines and stickers made by @b0rk. Certainly the pics don't make justice to the impressive quality of the paper and the print. I hope more zines get the print version! pic.twitter.com/mdoEtlZPe7

— Raymundo Cassani (@r_cassani) June 24, 2021

Received my Bite Size books and stickers from @b0rk today! They are beautiful! #linux #bash #networking pic.twitter.com/AkCKnOQ7bO

— Paul Mora (@pmora_ttc) June 7, 2021

Got my Bite Size collection from @b0rk! 😍 Really appreciate this work, and the zines look amazing! pic.twitter.com/x7DZyWpwJP

— Luana (@lnplgv) June 23, 2021

inspired by @b0rk, @actuallysoham and i made a zine for @mnwsth’s OS course and @b0rk graciously sent us some of her own zines and stickers! here’s to making programming concepts more accessible! pic.twitter.com/otKDglh3gV

— Tanvi Roy (@actuallytanvi) August 15, 2021

free shipping!

I never like paying for shipping, so I’ve set up free shipping for US orders over $30, and international orders over $50.

All of the shipping is being managed by a delightful small company called White Squirrel near Seattle, who specialize in shipping for artists. They’ve been a joy to work with for the last 4 months.

a discount if you already bought the PDF version!

If you already bought the PDF version of these zines – thank you so much!! You can use the PDFBUYER discount code for 50% off the print version. You’ll need to use the same email address you used when you bought the PDF. If you run into any problems with that, email me at julia@wizardzines.com.

all print zines include the PDF version too!

If you order the print version and you don’t already have the PDF version – it’s included! You’ll get a link with your confirmation email that’ll let you download the PDF right away.

discounts for buying zines in bulk!

If you want to buy your team zines for Christmas, there’s a 20% discount for orders over $300. Just use code TEAMZINES.

(this is the other thing that I said was “coming soon” last time :))

how to get my free zines in print: Your Linux Toolbox

You might notice that https://store.wizardzines.com doesn’t have print versions of my free zines (like “Networking! ACK!” or “So you want to be a wizard”). You can get those by buying the “Your Linux Toolbox” box set, this blog post has links to where to get it.

(if you’re wondering why Your Linux Toolbox is so much cheaper than the other print zines for sale: it’s pretty simple, it’s because I basically don’t make any money from it :). But it’s great – I love the box!! – and you should order it if you want my free zines in print!)

I’d love to be able to print a similar box for my other zines, but I haven’t found a company that will do it yet! Maybe one day!

working with small businesses that are close to each other is great

When I was originally thinking about how to ship, I considered getting the zines printed in China because it’s cheaper and that’s what a lot of publishers do.

Instead I decided to use a print company (Girlie Press) that’s in the same area as the company that handles my shipping (the Seattle area). I’m really happy with this choice even though it’s a bit more expensive because:

- The turnaround time is WAY faster – I can email them and get new zines printed and shipped to the warehouse super quickly. Which means that even if I do a preorder, people don’t actually have to wait that long to get their zines.

- Small businesses in general seem more flexible and easier to work with – for example a big fulfillment company I was considering told me that for them to ship stickers for me, every sticker needed to be individually barcoded. And they warned me not to ship them stickers shrink wrapped, because they might accidentally decide that 500 stickers is a single item and ship all 500 to one person. That kind of ridiculous mistake is a lot less likely to happen with a small business :)