Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Some notes on starting to use Django

Hello! One of my favourite things is starting to learn an Old Boring Technology that I’ve never tried before but that has been around for 20+ years. It feels really good when every problem I’m ever going to have has been solved already 1000 times and I can just get stuff done easily.

I’ve thought it would be cool to learn a popular web framework like Rails or Django or Laravel for a long time, but I’d never really managed to make it happen. But I started learning Django to make a website a few months back, I’ve been liking it so far, and here are a few quick notes!

less magic than Rails

I spent some time trying to learn Rails in 2020,

and while it was cool and I really wanted to like Rails (the Ruby community is great!),

I found that if I left my Rails project alone for months, when I came

back to it it was hard for me to remember how to get anything done because

(for example) if it says resources :topics in your routes.rb, on its own

that doesn’t tell you where the topics routes are configured, you need to

remember or look up the convention.

Being able to abandon a project for months or years and then come back to it is really important to me (that’s how all my projects work!), and Django feels easier to me because things are more explicit.

In my small Django project it feels like I just have 5 main files (other

than the settings files): urls.py, models.py, views.py, admin.py, and

tests.py, and if I want to know where something else is (like an HTML template)

is then it’s usually explicitly referenced from one of those files.

a built-in admin

For this project I wanted to have an admin interface to manually edit or view some of the data in the database. Django has a really nice built-in admin interface, and I can customize it with just a little bit of code.

For example, here’s part of one of my admin classes, which sets up which fields to display in the “list” view, which field to search on, and how to order them by default.

@admin.register(Zine)

class ZineAdmin(admin.ModelAdmin):

list_display = ["name", "publication_date", "free", "slug", "image_preview"]

search_fields = ["name", "slug"]

readonly_fields = ["image_preview"]

ordering = ["-publication_date"]

it’s fun to have an ORM

In the past my attitude has been “ORMs? Who needs them? I can just write my own SQL queries!”.

I’ve been enjoying Django’s ORM so far though, and I think it’s cool how Django

uses __ to represent a JOIN, like this:

Zine.objects

.exclude(product__order__email_hash=email_hash)

This query involves 5 tables: zines, zine_products, products, order_products, and orders.

To make this work I just had to tell Django that there’s a ManyToManyField

relating “orders” and “products”, and another ManyToManyField relating

“zines”, and “products”, so that it knows how to connect zines, orders, products.

I definitely could write that query, but writing product__order__email_hash is

a lot less typing, it feels a lot easier to read, and honestly I think it would

take me a little while to figure out how to construct the query

(which needs to do a few other things than just those joins).

I have zero concern about the performance of my ORM-generated queries so I’m pretty excited about ORMs for now, though I’m sure I’ll find things to be frustrated with eventually.

automatic migrations!

The other great thing about the ORM is migrations!

If I add, delete, or change a field in models.py, Django will automatically

generate a migration script like migrations/0006_delete_imageblob.py.

I assume that I could edit those scripts if I wanted, but so far I’ve just been running the generated scripts with no change and it’s been going great. It really feels like magic.

I’m realizing that being able to do migrations easily is important for me right now because I’m changing my data model fairly often as I figure out how I want it to work.

I like the docs

I had a bad habit of never reading the documentation but I’ve been really enjoying the parts of Django’s docs that I’ve read so far. This isn’t by accident: Jacob Kaplan-Moss has a talk from PyCon 2011 on Django’s documentation culture.

For example the intro to models lists the most important common fields you might want to set when using the ORM.

using sqlite

After having a bad experience trying to operate Postgres and not being able to

understand what was going on, I decided to run all of my small websites with

SQLite instead. It’s been going way better, and I love being able to backup by

just doing a VACUUM INTO and then copying the resulting single file.

I’ve been following these instructions for using SQLite with Django in production.

I think it should be fine because I’m expecting the site to have a few hundred writes per day at most, much less than Mess with DNS which has a lot more of writes and has been working well (though the writes are split across 3 different SQLite databases).

built in email (and more)

Django seems to be very “batteries-included”, which I love – if I want CSRF

protection, or a Content-Security-Policy, or I want to send email, it’s all

in there!

For example, I wanted to save the emails Django sends to a file in dev mode (so that it didn’t send real email to real people), which was just a little bit of configuration.

I just put this settings/dev.py:

EMAIL_BACKEND = "django.core.mail.backends.filebased.EmailBackend"

EMAIL_FILE_PATH = BASE_DIR / "emails"

and then set up the production email like this in settings/production.py

EMAIL_BACKEND = "django.core.mail.backends.smtp.EmailBackend"

EMAIL_HOST = "smtp.whatever.com"

EMAIL_PORT = 587

EMAIL_USE_TLS = True

EMAIL_HOST_USER = "xxxx"

EMAIL_HOST_PASSWORD = os.getenv('EMAIL_API_KEY')

That made me feel like if I want some other basic website feature, there’s likely to be an easy way to do it built into Django already.

the settings file still feels like a lot

I’m still a bit intimidated by the settings.py file: Django’s settings system

works by setting a bunch of global variables in a file, and I feel a bit

stressed about… what if I make a typo in the name of one of those variables?

How will I know? What if I type WSGI_APPLICATOIN = "config.wsgi.application"

instead of WSGI_APPLICATION?

I guess I’ve gotten used to having a Python language server tell me when I’ve made a typo and so now it feels a bit disorienting when I can’t rely on the language server support.

that’s all for now!

I haven’t really successfully used an actual web framework for a project before (right now almost all of my websites are either a single Go binary or static sites), so I’m interested in seeing how it goes!

There’s still lots for me to learn about, I still haven’t really gotten into Django’s form validation tooling or authentication systems.

Thanks to Marco Rogers for convincing me to give ORMs a chance.

(we’re still experimenting with the comments-on-Mastodon system! Here are the comments on Mastodon! tell me your favourite Django feature!)

A data model for Git (and other docs updates)

Hello! This past fall, I decided to take some time to work on Git’s documentation. I’ve been thinking about working on open source docs for a long time – usually if I think the documentation for something could be improved, I’ll write a blog post or a zine or something. But this time I wondered: could I instead make a few improvements to the official documentation?

So Marie and I made a few changes to the Git documentation!

a data model for Git

After a while working on the documentation, we noticed that Git uses the terms “object”, “reference”, or “index” in its documentation a lot, but that it didn’t have a great explanation of what those terms mean or how they relate to other core concepts like “commit” and “branch”. So we wrote a new “data model” document!

You can read the data model here for now. I assume at some point (after the next release?) it’ll also be on the Git website.

I’m excited about this because understanding how Git organizes its commit and branch data has really helped me reason about how Git works over the years, and I think it’s important to have a short (1600 words!) version of the data model that’s accurate.

The “accurate” part turned out to not be that easy: I knew the basics of how Git’s data model worked, but during the review process I learned some new details and had to make quite a few changes (for example how merge conflicts are stored in the staging area).

updates to git push, git pull, and more

I also worked on updating the introduction to some of Git’s core man pages. I quickly realized that “just try to improve it according to my best judgement” was not going to work: why should the maintainers believe me that my version is better?

I’ve seen a problem a lot when discussing open source documentation changes where 2 expert users of the software argue about whether an explanation is clear or not (“I think X would be a good way to explain it! Well, I think Y would be better!”)

I don’t think this is very productive (expert users of a piece of software are notoriously bad at being able to tell if an explanation will be clear to non-experts), so I needed to find a way to identify problems with the man pages that was a little more evidence-based.

getting test readers to identify problems

I asked for test readers on Mastodon to read the current version of documentation and tell me what they find confusing or what questions they have. About 80 test readers left comments, and I learned so much!

People left a huge amount of great feedback, for example:

- terminology they didn’t understand (what’s a pathspec? what does “reference” mean? does “upstream” have a specific meaning in Git?)

- specific confusing sentences

- suggestions of things things to add (“I do X all the time, I think it should be included here”)

- inconsistencies (“here it implies X is the default, but elsewhere it implies Y is the default”)

Most of the test readers had been using Git for at least 5-10 years, which I think worked well – if a group of test readers who have been using Git regularly for 5+ years find a sentence or term impossible to understand, it makes it easy to argue that the documentation should be updated to make it clearer.

I thought this “get users of the software to comment on the existing documentation and then fix the problems they find” pattern worked really well and I’m excited about potentially trying it again in the future.

the man page changes

We ended updating these 4 man pages:

git add(before, after)git checkout(before, after)git push(before, after)git pull(before, after)

The git push and git pull changes were the most interesting to me: in

addition to updating the intro to those pages, we also ended up writing:

- a section describing what the term “upstream branch” means (which previously wasn’t really explained)

- a cleaned-up description of what a “push refspec” is

Making those changes really gave me an appreciation for how much work it is

to maintain open source documentation: it’s not easy to write things that are

both clear and true, and sometimes we had to make compromises, for example the sentence

“git push may fail if you haven’t set an upstream for the current branch,

depending on what push.default is set to.” is a little vague, but the exact

details of what “depending” means are really complicated and untangling that is

a big project.

on the process for contributing to Git

It took me a while to understand Git’s development process. I’m not going to try to describe it here (that could be a whole other post!), but a few quick notes:

- Git has a Discord server with a “my first contribution” channel for help with getting started contributing. I found people to be very welcoming on the Discord.

- I used GitGitGadget to make all of my contributions. This meant that I could make a GitHub pull request (a workflow I’m comfortable with) and GitGitGadget would convert my PRs into the system the Git developers use (emails with patches attached). GitGitGadget worked great and I was very grateful to not have to learn how to send patches by email with Git.

- Otherwise I used my normal email client (Fastmail’s web interface) to reply to emails, wrapping my text to 80 character lines since that’s the mailing list norm.

I also found the mailing list archives on lore.kernel.org hard to navigate, so I hacked together my own git list viewer to make it easier to read the long mailing list threads.

Many people helped me navigate the contribution process and review the changes: thanks to Emily Shaffer, Johannes Schindelin (the author of GitGitGadget), Patrick Steinhardt, Ben Knoble, Junio Hamano, and more.

(I’m experimenting with comments on Mastodon, you can see the comments here)

Notes on switching to Helix from vim

Hello! Earlier this summer I was talking to a friend about how much I love using fish, and how I love that I don’t have to configure it. They said that they feel the same way about the helix text editor, and so I decided to give it a try.

I’ve been using it for 3 months now and here are a few notes.

why helix: language servers

I think what motivated me to try Helix is that I’ve been trying to get a working language server setup (so I can do things like “go to definition”) and getting a setup that feels good in Vim or Neovim just felt like too much work.

After using Vim/Neovim for 20 years, I’ve tried both “build my own custom configuration from scratch” and “use someone else’s pre-buld configuration system” and even though I love Vim I was excited about having things just work without having to work on my configuration at all.

Helix comes with built in language server support, and it feels nice to be able to do things like “rename this symbol” in any language.

the search is great

One of my favourite things about Helix is the search! If I’m searching all the files in my repository for a string, it lets me scroll through the potential matching files and see the full context of the match, like this:

For comparison, here’s what the vim ripgrep plugin I’ve been using looks like:

There’s no context for what else is around that line.

the quick reference is nice

One thing I like about Helix is that when I press g, I get a little help popup

telling me places I can go. I really appreciate this because I don’t often use

the “go to definition” or “go to reference” feature and I often forget the

keyboard shortcut.

some vim -> helix translations

- Helix doesn’t have marks like

ma,'a, instead I’ve been usingCtrl+OandCtrl+Ito go back (or forward) to the last cursor location - I think Helix does have macros, but I’ve been using multiple cursors in every

case that I would have previously used a macro. I like multiple cursors a lot

more than writing macros all the time. If I want to batch change something in

the document, my workflow is to press

%(to highlight everything), thensto select (with a regex) the things I want to change, then I can just edit all of them as needed. - Helix doesn’t have neovim-style tabs, instead it has a nice buffer switcher (

<space>b) I can use to switch to the buffer I want. There’s a pull request here to implement neovim-style tabs. There’s also a settingbufferline="multiple"which can act a bit like tabs withgp,gnfor prev/next “tab” and:bcto close a “tab”.

some helix annoyances

Here’s everything that’s annoyed me about Helix so far.

- I like the way Helix’s

:reflowworks much less than how vim reflows text withgq. It doesn’t work as well with lists. (github issue) - If I’m making a Markdown list, pressing “enter” at the end of a list item won’t continue the list. There’s a partial workaround for bulleted lists but I don’t know one for numbered lists.

- No persistent undo yet: in vim I could use an undofile so that I could undo changes even after quitting. Helix doesn’t have that feature yet. (github PR)

- Helix doesn’t autoreload files after they change on disk, I have to run

:reload-all(:ra<tab>) to manually reload them. Not a big deal. - Sometimes it crashes, maybe every week or so. I think it might be this issue.

The “markdown list” and reflowing issues come up a lot for me because I spend a lot of time editing Markdown lists, but I keep using Helix anyway so I guess they can’t be making me that mad.

switching was easier than I thought

I was worried that relearning 20 years of Vim muscle memory would be really hard.

It turned out to be easier than I expected, I started using Helix on a vacation for a little low-stakes coding project I was doing on the side and after a week or two it didn’t feel so disorienting anymore. I think it might be hard to switch back and forth between Vim and Helix, but I haven’t needed to use Vim recently so I don’t know if that’ll ever become an issue for me.

The first time I tried Helix I tried to force it to use keybindings that were more similar to Vim and that did not work for me. Just learning the “Helix way” was a lot easier.

There are still some things that throw me off: for example w in vim and w in

Helix don’t have the same idea of what a “word” is (the Helix one includes the

space after the word, the Vim one doesn’t).

using a terminal-based text editor

For many years I’d mostly been using a GUI version of vim/neovim, so switching to actually using an editor in the terminal was a bit of an adjustment.

I ended up deciding on:

- Every project gets its own terminal window, and all of the tabs in that window (mostly) have the same working directory

- I make my Helix tab the first tab in the terminal window

It works pretty well, I might actually like it better than my previous workflow.

my configuration

I appreciate that my configuration is really simple, compared to my neovim configuration which is hundreds of lines. It’s mostly just 4 keyboard shortcuts.

theme = "solarized_light"

[editor]

# Sync clipboard with system clipboard

default-yank-register = "+"

[keys.normal]

# I didn't like that Ctrl+C was the default "toggle comments" shortcut

"#" = "toggle_comments"

# I didn't feel like learning a different way

# to go to the beginning/end of a line so

# I remapped ^ and $

"^" = "goto_first_nonwhitespace"

"$" = "goto_line_end"

[keys.select]

"^" = "goto_first_nonwhitespace"

"$" = "goto_line_end"

[keys.normal.space]

# I write a lot of text so I need to constantly reflow,

# and missed vim's `gq` shortcut

l = ":reflow"

There’s a separate languages.toml configuration where I set some language

preferences, like turning off autoformatting.

For example, here’s my Python configuration:

[[language]]

name = "python"

formatter = { command = "black", args = ["--stdin-filename", "%{buffer_name}", "-"] }

language-servers = ["pyright"]

auto-format = false

we’ll see how it goes

Three months is not that long, and it’s possible that I’ll decide to go back to Vim at some point. For example, I wrote a post about switching to nix a while back but after maybe 8 months I switched back to Homebrew (though I’m still using NixOS to manage one little server, and I’m still satisfied with that).

New zine: The Secret Rules of the Terminal

Hello! After many months of writing deep dive blog posts about the terminal, on Tuesday I released a new zine called “The Secret Rules of the Terminal”!

You can get it for $12 here: https://wizardzines.com/zines/terminal, or get an 15-pack of all my zines here.

Here’s the cover:

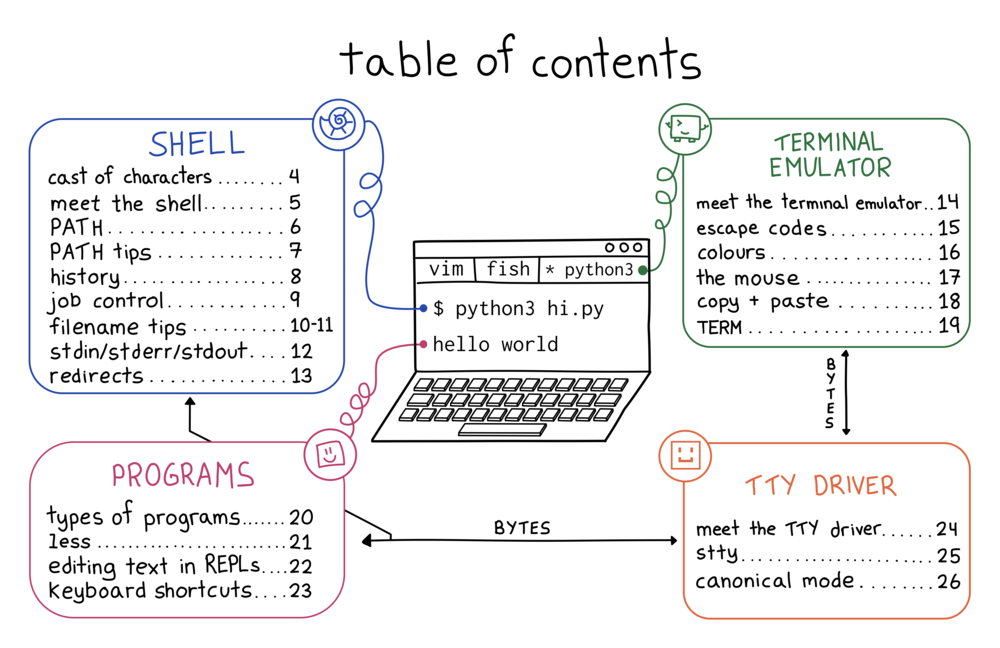

the table of contents

Here’s the table of contents:

why the terminal?

I’ve been using the terminal every day for 20 years but even though I’m very confident in the terminal, I’ve always had a bit of an uneasy feeling about it. Usually things work fine, but sometimes something goes wrong and it just feels like investigating it is impossible, or at least like it would open up a huge can of worms.

So I started trying to write down a list of weird problems I’ve run into in terminal and I realized that the terminal has a lot of tiny inconsistencies like:

- sometimes you can use the arrow keys to move around, but sometimes pressing the arrow keys just prints

^[[D - sometimes you can use the mouse to select text, but sometimes you can’t

- sometimes your commands get saved to a history when you run them, and sometimes they don’t

- some shells let you use the up arrow to see the previous command, and some don’t

If you use the terminal daily for 10 or 20 years, even if you don’t understand exactly why these things happen, you’ll probably build an intuition for them.

But having an intuition for them isn’t the same as understanding why they happen. When writing this zine I actually had to do a lot of work to figure out exactly what was happening in the terminal to be able to talk about how to reason about it.

the rules aren’t written down anywhere

It turns out that the “rules” for how the terminal works (how do

you edit a command you type in? how do you quit a program? how do you fix your

colours?) are extremely hard to fully understand, because “the terminal” is actually

made of many different pieces of software (your terminal emulator, your

operating system, your shell, the core utilities like grep, and every other random

terminal program you’ve installed) which are written by different people with different

ideas about how things should work.

So I wanted to write something that would explain:

- how the 4 pieces of the terminal (your shell, terminal emulator, programs, and TTY driver) fit together to make everything work

- some of the core conventions for how you can expect things in your terminal to work

- lots of tips and tricks for how to use terminal programs

this zine explains the most useful parts of terminal internals

Terminal internals are a mess. A lot of it is just the way it is because someone made a decision in the 80s and now it’s impossible to change, and honestly I don’t think learning everything about terminal internals is worth it.

But some parts are not that hard to understand and can really make your experience in the terminal better, like:

- if you understand what your shell is responsible for, you can configure your shell (or use a different one!) to access your history more easily, get great tab completion, and so much more

- if you understand escape codes, it’s much less scary when

cating a binary to stdout messes up your terminal, you can just typeresetand move on - if you understand how colour works, you can get rid of bad colour contrast in your terminal so you can actually read the text

I learned a surprising amount writing this zine

When I wrote How Git Works, I thought I

knew how Git worked, and I was right. But the terminal is different. Even

though I feel totally confident in the terminal and even though I’ve used it

every day for 20 years, I had a lot of misunderstandings about how the terminal

works and (unless you’re the author of tmux or something) I think there’s a

good chance you do too.

A few things I learned that are actually useful to me:

- I understand the structure of the terminal better and so I feel more confident debugging weird terminal stuff that happens to me (I was even able to suggest a small improvement to fish!). Identifying exactly which piece of software is causing a weird thing to happen in my terminal still isn’t easy but I’m a lot better at it now.

- you can write a shell script to copy to your clipboard over SSH

- how

resetworks under the hood (it does the equivalent ofstty sane; sleep 1; tput reset) – basically I learned that I don’t ever need to worry about rememberingstty saneortput resetand I can just runresetinstead - how to look at the invisible escape codes that a program is printing out (run

unbuffer program > out; less out) - why the builtin REPLs on my Mac like

sqlite3are so annoying to use (they uselibeditinstead ofreadline)

blog posts I wrote along the way

As usual these days I wrote a bunch of blog posts about various side quests:

- How to add a directory to your PATH

- “rules” that terminal problems follow

- why pipes sometimes get “stuck”: buffering

- some terminal frustrations

- ASCII control characters in my terminal on “what’s the deal with Ctrl+A, Ctrl+B, Ctrl+C, etc?”

- entering text in the terminal is complicated

- what’s involved in getting a “modern” terminal setup?

- reasons to use your shell’s job control

- standards for ANSI escape codes, which is really me trying to figure out if I think the

terminfodatabase is serving us well today

people who helped with this zine

A long time ago I used to write zines mostly by myself but with every project I get more and more help. I met with Marie Claire LeBlanc Flanagan every weekday from September to June to work on this one.

The cover is by Vladimir Kašiković, Lesley Trites did copy editing, Simon Tatham (who wrote PuTTY) did technical review, our Operations Manager Lee did the transcription as well as a million other things, and Jesse Luehrs (who is one of the very few people I know who actually understands the terminal’s cursed inner workings) had so many incredibly helpful conversations with me about what is going on in the terminal.

get the zine

Here are some links to get the zine again:

As always, you can get either a PDF version to print at home or a print version shipped to your house. The only caveat is print orders will ship in August – I need to wait for orders to come in to get an idea of how many I should print before sending it to the printer.

Using `make` to compile C programs (for non-C-programmers)

I have never been a C programmer but every so often I need to compile a C/C++

program from source. This has been kind of a struggle for me: for a

long time, my approach was basically “install the dependencies, run make, if

it doesn’t work, either try to find a binary someone has compiled or give up”.

“Hope someone else has compiled it” worked pretty well when I was running Linux but since I’ve been using a Mac for the last couple of years I’ve been running into more situations where I have to actually compile programs myself.

So let’s talk about what you might have to do to compile a C program! I’ll use a couple of examples of specific C programs I’ve compiled and talk about a few things that can go wrong. Here are three programs we’ll be talking about compiling:

step 1: install a C compiler

This is pretty simple: on an Ubuntu system if I don’t already have a C compiler I’ll install one with:

sudo apt-get install build-essential

This installs gcc, g++, and make. The situation on a Mac is more

confusing but it’s something like “install xcode command line tools”.

step 2: install the program’s dependencies

Unlike some newer programming languages, C doesn’t have a dependency manager. So if a program has any dependencies, you need to hunt them down yourself. Thankfully because of this, C programmers usually keep their dependencies very minimal and often the dependencies will be available in whatever package manager you’re using.

There’s almost always a section explaining how to get the dependencies in the README, for example in paperjam’s README, it says:

To compile PaperJam, you need the headers for the libqpdf and libpaper libraries (usually available as libqpdf-dev and libpaper-dev packages).

You may need

a2x(found in AsciiDoc) for building manual pages.

So on a Debian-based system you can install the dependencies like this.

sudo apt install -y libqpdf-dev libpaper-dev

If a README gives a name for a package (like libqpdf-dev), I’d basically

always assume that they mean “in a Debian-based Linux distro”: if you’re on a

Mac brew install libqpdf-dev will not work. I still have not 100% gotten

the hang of developing on a Mac yet so I don’t have many tips there yet. I

guess in this case it would be brew install qpdf if you’re using Homebrew.

step 3: run ./configure (if needed)

Some C programs come with a Makefile and some instead come with a script called

./configure. For example, if you download sqlite’s source code, it has a ./configure script in

it instead of a Makefile.

My understanding of this ./configure script is:

- You run it, it prints out a lot of somewhat inscrutable output, and then it

either generates a

Makefileor fails because you’re missing some dependency - The

./configurescript is part of a system called autotools that I have never needed to learn anything about beyond “run it to generate aMakefile”.

I think there might be some options you can pass to get the ./configure

script to produce a different Makefile but I have never done that.

step 4: run make

The next step is to run make to try to build a program. Some notes about

make:

- Sometimes you can run

make -j8to parallelize the build and make it go faster - It usually prints out a million compiler warnings when compiling the program. I always just ignore them. I didn’t write the software! The compiler warnings are not my problem.

compiler errors are often dependency problems

Here’s an error I got while compiling paperjam on my Mac:

/opt/homebrew/Cellar/qpdf/12.0.0/include/qpdf/InputSource.hh:85:19: error: function definition does not declare parameters

85 | qpdf_offset_t last_offset{0};

| ^

Over the years I’ve learned it’s usually best not to overthink problems like

this: if it’s talking about qpdf, there’s a good change it just means that

I’ve done something wrong with how I’m including the qpdf dependency.

Now let’s talk about some ways to get the qpdf dependency included in the right way.

the world’s shortest introduction to the compiler and linker

Before we talk about how to fix dependency problems: building C programs is split into 2 steps:

- Compiling the code into object files (with

gccorclang) - Linking those object files into a final binary (with

ld)

It’s important to know this when building a C program because sometimes you need to pass the right flags to the compiler and linker to tell them where to find the dependencies for the program you’re compiling.

make uses environment variables to configure the compiler and linker

If I run make on my Mac to install paperjam, I get this error:

c++ -o paperjam paperjam.o pdf-tools.o parse.o cmds.o pdf.o -lqpdf -lpaper

ld: library 'qpdf' not found

This is not because qpdf is not installed on my system (it actually is!). But

the compiler and linker don’t know how to find the qpdf library. To fix this, we need to:

- pass

"-I/opt/homebrew/include"to the compiler (to tell it where to find the header files) - pass

"-L/opt/homebrew/lib -liconv"to the linker (to tell it where to find library files and to link iniconv)

And we can get make to pass those extra parameters to the compiler and linker using environment variables!

To see how this works: inside paperjam’s Makefile you can see a bunch of environment variables, like LDLIBS here:

paperjam: $(OBJS)

$(LD) -o $@ $^ $(LDLIBS)

Everything you put into the LDLIBS environment variable gets passed to the

linker (ld) as a command line argument.

secret environment variable: CPPFLAGS

Makefiles sometimes define their own environment variables that they pass to

the compiler/linker, but make also has a bunch of “implicit” environment

variables which it will automatically pass to the C compiler and linker. There’s a full list of implicit environment variables here,

but one of them is CPPFLAGS, which gets automatically passed to the C compiler.

(technically it would be more normal to use CXXFLAGS for this, but this

particular Makefile hardcodes CXXFLAGS so setting CPPFLAGS was the only

way I could find to set the compiler flags without editing the Makefile)

two ways to pass environment variables to make

I learned thanks to @zwol that there are actually two ways to pass environment variables to make:

CXXFLAGS=xyz make(the usual way)make CXXFLAGS=xyz

The difference between them is that make CXXFLAGS=xyz will override the

value of CXXFLAGS set in the Makefile but CXXFLAGS=xyz make won’t.

I’m not sure which way is the norm but I’m going to use the first way in this post.

how to use CPPFLAGS and LDLIBS to fix this compiler error

Now that we’ve talked about how CPPFLAGS and LDLIBS get passed to the

compiler and linker, here’s the final incantation that I used to get the

program to build successfully!

CPPFLAGS="-I/opt/homebrew/include" LDLIBS="-L/opt/homebrew/lib -liconv" make paperjam

This passes -I/opt/homebrew/include to the compiler and -L/opt/homebrew/lib -liconv to the linker.

Also I don’t want to pretend that I “magically” knew that those were the right arguments to pass, figuring them out involved a bunch of confused Googling that I skipped over in this post. I will say that:

- the

-Icompiler flag tells the compiler which directory to find header files in, like/opt/homebrew/include/qpdf/QPDF.hh - the

-Llinker flag tells the linker which directory to find libraries in, like/opt/homebrew/lib/libqpdf.a - the

-llinker flag tells the linker which libraries to link in, like-liconvmeans “link in theiconvlibrary”, or-lmmeans “linkmath”

tip: how to just build 1 specific file: make $FILENAME

Yesterday I discovered this cool tool called

qf which you can use to quickly

open files from the output of ripgrep.

qf is in a big directory of various tools, but I only wanted to compile qf.

So I just compiled qf, like this:

make qf

Basically if you know (or can guess) the output filename of the file you’re

trying to build, you can tell make to just build that file by running make $FILENAME

tip: you don’t need a Makefile

I sometimes write 5-line C programs with no dependencies, and I just learned

that if I have a file called blah.c, I can just compile it like this without creating a Makefile:

make blah

It gets automaticaly expanded to cc -o blah blah.c, which saves a bit of

typing. I have no idea if I’m going to remember this (I might just keep typing

gcc -o blah blah.c anyway) but it seems like a fun trick.

tip: look at how other packaging systems built the same C program

If you’re having trouble building a C program, maybe other people had problems building it too! Every Linux distribution has build files for every package that they build, so even if you can’t install packages from that distribution directly, maybe you can get tips from that Linux distro for how to build the package. Realizing this (thanks to my friend Dave) was a huge ah-ha moment for me.

For example, this line from the nix package for paperjam says:

env.NIX_LDFLAGS = lib.optionalString stdenv.hostPlatform.isDarwin "-liconv";

This is basically saying “pass the linker flag -liconv to build this on a

Mac”, so that’s a clue we could use to build it.

That same file also says env.NIX_CFLAGS_COMPILE = "-DPOINTERHOLDER_TRANSITION=1";. I’m not sure what this means, but when I try

to build the paperjam package I do get an error about something called a

PointerHolder, so I guess that’s somehow related to the “PointerHolder

transition”.

step 5: installing the binary

Once you’ve managed to compile the program, probably you want to install it somewhere!

Some Makefiles have an install target that let you install the tool on your

system with make install. I’m always a bit scared of this (where is it going

to put the files? what if I want to uninstall them later?), so if I’m compiling

a pretty simple program I’ll often just manually copy the binary to install it

instead, like this:

cp qf ~/bin

step 6: maybe make your own package!

Once I figured out how to do all of this, I realized that I could use my new

make knowledge to contribute a paperjam package to Homebrew! Then I could

just brew install paperjam on future systems.

The good thing is that even if the details of how all of the different packaging systems, they fundamentally all use C compilers and linkers.

it can be useful to understand a little about C even if you’re not a C programmer

I think all of this is an interesting example of how it can useful to understand some basics of how C programs work (like “they have header files”) even if you’re never planning to write a nontrivial C program if your life.

It feels good to have some ability to compile C/C++ programs myself, even

though I’m still not totally confident about all of the compiler and linker

flags and I still plan to never learn anything about how autotools works other

than “you run ./configure to generate the Makefile”.

Two things I left out of this post:

LD_LIBRARY_PATH / DYLD_LIBRARY_PATH(which you use to tell the dynamic linker at runtime where to find dynamically linked files) because I can’t remember the last time I ran into anLD_LIBRARY_PATHissue and couldn’t find an example.pkg-config, which I think is important but I don’t understand yet