Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Re: Support Black-Owned Businesses: 181 Places to Start Online

A reader sent me a link to a blog post that lists 181 black-owned businesses by category. They wrote:

The events of last summer (BLM protests and COVID-19) saw many people rally to support Black-owned businesses. Sadly, since summer ended, people forgot to keep sharing and supporting these businesses.

I just found a new article with links to more than 150 Black-owned businesses. I was so happy to see that people still care about helping these companies thrive!

Thanks for the resource!

NFTs, Art, and Digital Ownership

If you’ve been following cryptocurrency1 news lately, or really tech news in general, you’ve probably heard about NFTs (non-fungible tokens). A lot of the articles and discussions I’ve seen about them are from people who are less interested in the actual technology and long term implications of cryptocurrency and more in the profits they can gain from it (just like with Bitcoin itself).

I’m not one of those people. I find the tech extremely interesting, but the practical use is overshadowed by the massive amount of energy consumption that’s necessary for many of these currencies to function2.

I want to talk about what NFTs are, how they work, how digital ownership of things compares to physical ownership, and why even as a future oriented person who owns a lot of digital shit, this doesn’t really add up to me.

I’ll start with an explanation of some of the terms.

Cryptocurrency

Bitcoin, Ethereum, Stellar Lumens, Litecoin, Dogecoin, etc. Each one is an independent ledger (called a blockchain) that keeps track of which accounts/addresses have how much currency. Each entry in the ledger says something like “this address sent this many units of currency to this other address”.

Each one of these ledgers/blockchains is distributed through the internet. For those of you who are familiar with BitTorrent, imagine creating a spreadsheet that keeps track of how much currency everyone owes everyone else and then uploading it to a torrent site so anyone who wants to see it can always download it from anyone else who has it.

Through lots of math, cryptography, and a very interesting and complicated protocol3, these ledgers/blockchains/spreadsheets (whatever analogy makes the most sense) are secured against people lying about how much they’ve spent or when they spent it.

NFTs

Non-fungible tokens are related to (and a form of) cryptocurrency. But while both a dollar and a bitcoin are fungible (it doesn’t matter WHICH 1 dollar bill you have; if you have a dollar, you have 1 dollar), each non-fungible token is unique. You can make a dollar bill non-fungible by drawing a unique piece of art on it. Now that specific dollar is unique and has a different value than other dollar bills.

So, similar to the dollar with the art on it, an NFT is a unit of Ethereum cryptocurrency that’s unique and describes itself as a specific thing (like a song, a piece of art, or anything really).

Ethereum is interesting because an address can also contain code along with data. Any program that exists on the Ethereum ledger/blockchain is called a Smart Contract. It’s basically programmable currency, and it’s one of key parts of NFTs.

So that’s:

- A secure ledger that can’t be tampered with that describes exactly which addresses own which tokens

- The ability to store both data and code in this ledger

- People with digital goods/works/art to sell

Digital Ownership

Putting all that together, there’s now the ability to securely buy and sell digital representations of anything by creating a NFT that says it’s a thing and is cryptographically signed by the creator. The only way to change ownership is through a valid transaction.

Unforgeable digital ownership of things.

Already this is interesting enough to artists/fans/collectors, but it’s even more interesting when you consider that a Smart Contract can specify something like “any time this token is sold, send this percentage of that transaction to a specific address.”

Which means the potential for automatic, perpetual, built-in royalties for the first owner/creator of the NFT (if programmed to do so).

The NFT Craze

In addition to artists creating NFTs for their works, anyone who owns anything notable are getting involved. Jack Dorsey (creator of Twitter) is selling the NFT for his first tweet. How? He went to a website called Valuables that manages NFT auctions. They’ll create a digital representation of his tweet (which they state is “signed by the original owner”), and make sure his account/Ethereum address owns it. Once the auction is won, the transaction will happen just like it would if it was a fungible Ethereum token.

There will always be a record of this transaction in the blockchain, and proof that there’s a new owner. This token can continue to be bought/sold just like a physical object. The current bid as of this writing is $2.5 million.

- Grimes just recently sold $6,000,000 worth of art as NFTs.

- Nyan Cat was purchased for about $536,571.

- A group of anonymous art enthusiasts created an NFT of a Banksy screenprint and then burned the original work so that it only exists digitally. The NFT sold for $394,000.

NFTs, art, and the physical world

Even as we continue to digitize everything we do and own, people will always want to be able to say they own unique shit. This kind of thing is inevitable. But do NFTs actually make sense?

“Owning” a physical work of art doesn’t mean you own all the rights to the work right? There’s a long history of laws, copyright acts, and lawsuits over the exact rights between creators and buyers of visual art. For example, buying a piece of art doesn’t mean you automatically get the rights to make and sell derivative works.

Some rights art collectors/owners do have:

- Showing or withholding the original work to/from others

- Loaning the original work to a museum or other organization

- Decorating their home with the original work

- Telling people they own the original work

- Selling the original work to someone else

How does that compare to the rights granted to art-based NFT owners?

Showing or withholding the original work to/from othersLoaning the original work to a museum or other organizationDecorating their home with the original work- Telling people they own the

original workNFT - Selling the

original workNFT to someone else

It just doesn’t seem like a great comparison.

Artists, Celebrities, and Gettin Paid

A lot of the excitement I’m seeing about NFTs are about more artists getting paid for their work more often. Especially considering automatic and perpetual royalties to artists are now possible. That part sounds like a great thing.

But wouldn’t an artist need enough exposure and success to have buyers interested in “owning” their original works in the first place? I’m not seeing this helping the artists who actually need help.

All of the big NFT sales I’ve seen so far are from people who can already easily monetize their popularity. Jacob Kastrenakes from the The Verge article I referenced earlier:

Grimes is the latest artist to get in on the NFT gold rush, selling around $6 million worth of digital artworks after putting them up for auction yesterday.

…

The bulk of the sales came from two pieces with thousands of copies available that sold for $7,500 each. The works, titled “Earth” and “Mars,” are both short videos featuring their titular planet with a giant cherub over it holding a weapon, also set to original music. Nearly 700 copies were sold for a total of $5.18 million before sales closed.

So she sold 700 “unique” tokens for a thing you can fully experience right there on the purchase page?

Is this just a new, extremely energy wasteful way for people who already have money and the ability to make lots of money… make even more money?

-

I always refer to it as cryptocurrency, not just crypto. I’m a relatively security (and encryption) focused developer. To me, crypto means the general field of cryptography, which really fucking interesting and is more than just 💸💰 ↩︎

-

One of the methods for keeping a cryptocurrency functioning securely is something called “proof of work”. The computers gathering and storing transactions into a blockchain solve mathematical “problems” (puzzles) that are hard to answer but easy to verify (the opposite of encryption techniques that are easy to generate, but very hard to solve/break). These puzzles, which are core to how the currency functions, are made to stay hard to solve even as computers get faster. By design, “proof of work” based cryptocurrencies must always use huge amounts of energy. ↩︎

-

Check out this very long but very interesting article about some of the details how blockchain protocols use “proof of work” to manage the ordering and timing of transactions. ↩︎

Fetching Emails in Go With JMAP

I wrote an article a while back about switching my email provider from Gmail to Fastmail. Back when I was trying to figure out which service to switch to, I came across a blog post (written in 2019) from Fastmail about publishing the standard for their JMAP protocol. I knew about POP3 and IMAP just from trying to configure mail clients over the years, but I never implemented anything on the server or client for email.

I still don’t have that much of a reason to use JMAP with anything since 1. I’m not really a heavy email user and 2. there’s already an email app on every device I use. But I was still curious about the protocol for some reason so I decided to build some “small” email features into the website so I can read and archive my email from the admin section.

Here’s what I ended up doing.

About JMAP

Most email providers support both IMAP and some kind of custom API (which each provider promises is the fastest and most efficient API possible) for access to email. Fastmail introduced JMAP as their “better than IMAP” API back in 2014.

Fastmail decided to publish the JMAP specs as a standard to encourage other email providers to use it too. I don’t know of any other services using it yet, but I figured it’s probably still a good thing for me to know anyway. No matter how many different products and services are created for messaging and communication, email is always something to fall back on.

Now I just had to think of something useful/interesting to build.

The Feature

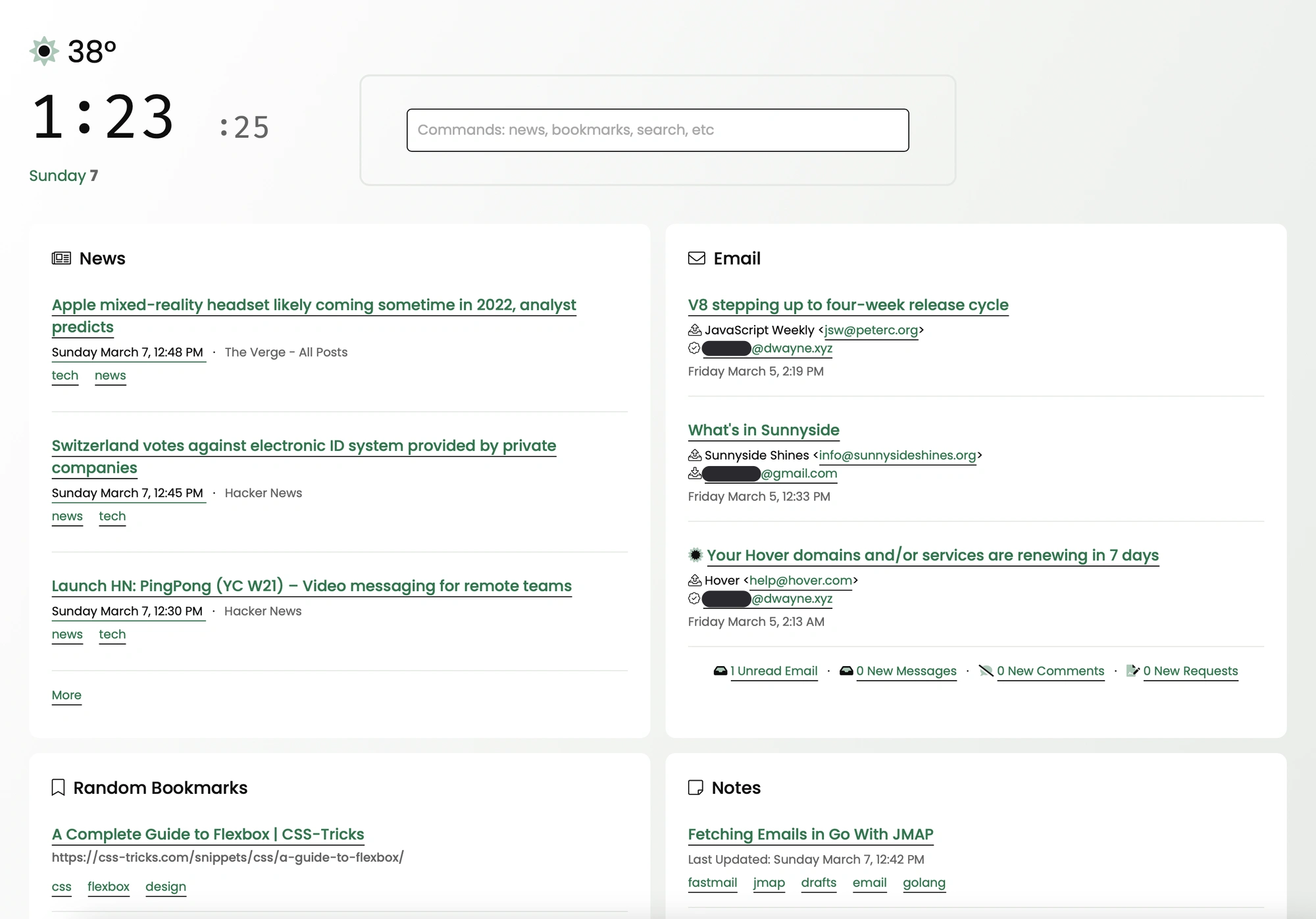

I made a start page for myself a little while ago. If you’re logged in as an admin (I’m the only one that can log in as an admin), it shows most recently updated notes and site notifications and stuff. I have it set to my new tab page in my browser.

Since I already had notifications on the page, I thought it made sense to use Fastmail’s JMAP API to show the latest three emails in my inbox on the page too.

At first I was planning to have the main link for each of the three emails go to the Fastmail web client page for it, but by the time I was done, I also added the ability to display a whole email thread and the inbox itself (with pagination1).

I figured this would be a good start to building even more useful email related features as the website continues to evolve.

Golang and JMAP

This website is very backend/server driven. I’ve been doing a lot of frontend React/Redux/Vue stuff over the years, and I wanted to switch it up for this project and go back to fully server side rendered pages and minimal client-side/Javascript features. So before I even knew exactly what I was gonna use JMAP for, I knew it would require figuring out how to make JMAP formatted requests from Go (golang).

The libraries page of the JMAP website doesn’t list any for Go, but after all the code I wrote to format and parse both JSON (weather, Steam, and Spotify APIs) and XML (RSS feed) requests and responses, I figured it wouldn’t be too difficult to deal with this the same way. I was mostly right until I actually tried parsing the JMAP responses.

JSON (and XML) Parsing in Go

Both JSON and XML parsing are both done the same way in Go (using the standard library). You describe all the fields of a struct with named attributes (they look like json:"userId"), and then pass both the JSON/XML data and an empty struct to the xml.Unmarshal method and it’ll fill the struct with the parsed data.

So for example, on my About Me page, I use the Steam API to get the list of games. The JSON response from Steam looks like this:

1{ 2 "response": { 3 "total_count": 5, 4 "games": [ 5 { 6 "appid": 289070, 7 "name": "Sid Meier's Civilization VI", 8 "playtime_2weeks": 1015, 9 "playtime_forever": 60809, 10 "img_icon_url": "9dc914132fec244adcede62fb8e7524a72a7398c", 11 "img_logo_url": "356443a094f8e20ce21293039d7226eac3d3b4d9", 12 "playtime_windows_forever": 20608, 13 "playtime_mac_forever": 0, 14 "playtime_linux_forever": 0 15 }, 16 { 17 "appid": 860510, 18 "name": "Little Nightmares II", 19 "playtime_2weeks": 755, 20 "playtime_forever": 755, 21 "img_icon_url": "8875efb23a0fc1f079f227508d981f2cba82d735", 22 "img_logo_url": "19b6e7fc830b2a752891a9a23afdc3fe94dc5d6b", 23 "playtime_windows_forever": 755, 24 "playtime_mac_forever": 0, 25 "playtime_linux_forever": 0 26 }, 27 ] 28 } 29}

So I created these structs:

1type SteamGame struct { 2 AppID int `json:"appid"` 3 Name string `json:"name"` 4 PlayTime int `json:"playtime_2weeks"` 5 PlayTimeForever int `json:"playtime_forever"` 6 ImageIconURL string `json:"img_icon_url"` 7 ImageLogoURL string `json:"img_logo_url"` 8 PlayTimeString string `json:"playtime_string"` 9} 10 11type SteamRecentGamesResponseObject struct { 12 Total int `json:"total_count"` 13 Games []SteamGame `json:"games"` 14} 15 16type SteamRecentGamesResponse struct { 17 Response SteamRecentGamesResponseObject `json:"response"` 18}

And then I can parse the JSON like this:

1var r SteamRecentGamesResponse 2 3res, err := http.Get(url) 4if err != nil { 5 return nil, err 6} 7 8defer res.Body.Close() 9body, err := ioutil.ReadAll(res.Body) 10if err != nil { 11 return nil, err 12} 13 14json.Unmarshal(body, &r) 15for _, game := range r.Response.Games { 16 ... 17}

I started to do something similar for the responses from JMAP, but there’s a problem right from the start. The main data type for the requests and responses is something they call an Invocation. An Invocation is a tuple2, of values, which is usually a string, then a JSON object (or map of strings to any JSON value), and then another string. If your HTTP request contains multiple Invocations, you’ll get more than one tuple back, so in JSON, it’s represented as an array of arrays.

Here’s a truncated example of one JMAP request with three Invocations:

1[ 2 [ "Email/query", { 3 "accountId": "...", 4 "filter": { 5 "inMailbox": "" 6 } 7 }, "0" ], 8 9 [ "Email/get", { 10 "accountId": "...", 11 "#ids": { 12 "name": "Email/query", 13 "path": "/ids", 14 "resultOf": "0" 15 } 16 }, "1" ], 17 18 [ "Thread/get", { 19 "accountId": "...", 20 "#ids": { 21 "name": "Email/get", 22 "path": "/list/*/threadId", 23 "resultOf": "1" 24 } 25 }, "2" ], 26]

The first tuple is for the Email/query request, the second for Email/get, and the last one is for Thread/get. The second value for each tuple is a JSON object/attribute map that act as the arguments for the call.

The result for a call like this would contain three Invocations in response:

1[ 2 [ "Email/query", { 3 "accountId": "...", 4 "ids": [ 5 "..." 6 ], 7 "queryState": "123:0", 8 "total": 10 9 }, "0" ], 10 11 [ "Email/get", { 12 "accountId": "...", 13 "list": [ 14 { "id": "...", "threadId": "..." } 15 ], 16 "state": "123", 17 "notFound": [] 18 }, "1" ], 19 20 [ "Thread/get", { 21 "accountId": "u123456", 22 "list": [ 23 { "id": "...", "emailIds": [] }, 24 ], 25 "state": "123" 26 }, "2" ], 27 28]

It’s a pretty good format that allows you to combine requests and have Invocations reference each other (the third tuple elements are Invocation IDs you provide for reference; see the resultOf attribute in the last request Invocation above).

Unfortunately there isn’t a great way to describe the tuples in these response types in Go.

Go’s type system

As you can see from the Steam API example above, Go is strongly typed. Before you can do anything with a variable, you have to know/describe its type. Arrays are always lists of one specific type of data. That type might be the “anything” type interface{}3.

So it’s possible to declare an array of strings, an array of attribute maps, or an array of “anything”, but not a strongly typed Invocation tuple.

Here’s an example struct with some fields one might think to use:

1type ExampleStruct struct { 2 StrArray []string 3 AttrMapArray []map[string]interface{} 4 5 AnythingArray []interface{} 6}

The first two fields, StrArray and AttrMapArray, wouldn’t work at all in this case (it would fail to parse). AnythingArray would work, but a type assertion would be needed on each element before use (which is a problem with the AttrMapArray too). Here’s an example of what that might look like:

1var s ExampleStruct 2 3// The first value might be something like "Email/get" 4strValue := s.AnythingArray[0].(string) 5 6// Response values as an attribute map 7mapValue := s.AnythingArray[1].(map[string]interface{}) 8 9// The list of emails in that attribute map 10list := mapValue["list"].([]interface{}) 11 12// The string ID of the first email in the list 13id := list[0]["id"].(string)

But it’s not good enough. It doesn’t even feel strongly typed anymore. The compiler can’t really check anything here, and it would be very easy to get any of the types wrong. It also looks weird.

I wanted a solution that’s at least somewhat type-safe and actually takes advantage of the features of Go.

Here’s what I came up with:

Requests and Responses

First, I made Invocation and APIRequest structs. The second element of an Invocation is a interface{} type. That value is always either a map[string]interface{} type or a JSON ready struct.

APIRequest is the struct I use to json.Marshal the entire request body. It describes the list of Invocations to send as an array of interface{} arrays.

1type APIRequest struct { 2 Using []string `json:"using"` 3 MethodCalls [][]interface{} `json:"methodCalls"` 4}

APIResponse is similar:

1type APIResponse struct { 2 SessionState string `json:"sessionState"` 3 MethodResponses [][]interface{} `json:"methodResponses"` 4}

Marshalling and Unmarshalling the Response

When I json.Unmarshal the response body, I get the Invocation responses as expected, but they still need type assertions. My solution was to add methods onto the APIResponse object to (1) find an Invocation by name (the first element of each of the MethodResponses arrays) and then (2) json.Marshal the value back into a byte array and then (3) json.Unmarshal that value back into the actual struct it should be.

1func (r *APIResponse) GetEmailResponse() *EmailResponse { 2 for _, response := range r.MethodResponses { 3 // (1) Type assertion for the name of the invocation 4 name := response[0].(string) 5 if name == "Email/get" { 6 var r EmailResponse 7 // (2) Marshal from interface{} back to byte array 8 value, err := json.Marshal(response[1]) 9 if err != nil { 10 logger.Logf("error marshalling json: %v", err) 11 return nil 12 } 13 // (3) Unmarshal to the correct struct (EmailResponse) 14 json.Unmarshal(value, &r) 15 return &r 16 } 17 } 18 return nil 19}

End Result

So now making a request looks something like this:

1// FetchEmail returns an email thread. 2func FetchEmail(id, threadID, accountID string) ([]*Email, error) { 3 calls := []*Invocation{ 4 { 5 Name: "Thread/get", 6 Value: GenericJSON{ 7 "accountId": accountID, 8 "ids": []string{ 9 threadID, 10 }, 11 }, 12 ID: "0", 13 }, 14 { 15 Name: "Email/get", 16 Value: GenericJSON{ 17 ... 18 }, 19 ID: "1", 20 }, 21 } 22 23 r, err := Request(calls) 24 if err != nil { 25 return nil, err 26 } 27 28 value := r.GetEmailResponse() 29 return value.List, nil 30}

The Value field for the Invocations that are passed to Request() are interface{} values, but using a map[string]interface{} type (which is what GenericJSON is) works. The compiler (and my editor) knows that the value variable returned from r.GetEmailResponse() is a *EmailResponse type, and that value.List is a []*Email type.

I like how this turned out so far. Adding other email functionality like marking threads as read, archiving/deleting mail, and adding caching (a start page is supposed to load as quickly as possible of course4) were all easy to add on top of this base.

I don’t feel like I have to go much further with this since I can do everything I need to do with email from my computer, phone, and watch, but it’s nice to know it wouldn’t be too hard to write an entire email client into this website if I wanted to.

-

I already standardized pagination throughout the website using limit and offset query params. The JMAP API uses limit and position arguments in a similar way, so it was very easy to set up. ↩︎

-

Tuples are like arrays, but behave differently in the languages that support them (usually more functional languages like Python, Swift, F#, etc). They’re a fixed length and explicitly support each element being a different data type. In loosely typed languages, arrays and tuples are conceptually pretty similar. ↩︎

-

Go has interfaces, which is a description of methods/functions. Any object that has those functions is considered one of that type.

interface{}means an interface with no described methods. All types fit that description, sointerface{}ends up meaning “any type”. ↩︎ -

Considering this is the page that I see every time I open a new tab or window, I didn’t want to make an actual request to Fastmail’s servers on each page load. At first, I started caching the parsed

[]*Emailresponse, but that didn’t really help anything. I just saw stale results sometimes and then “slow” (an additional 500 - 1000 ms wait) responses other times. Eventually I made the email request an API call (to my own backend) that’s made after the page is loaded. ↩︎

Stadia Continues to Struggle

Bloomberg just published an article about Google’s struggles with Stadia. Things really haven’t been going well.

From Jason Schreier:

Players also didn’t like Stadia’s business model, which required customers to buy games individually rather than subscribe to an all-you-can-play service à la Netflix or the Xbox’s Game Pass. Paying as much as $60 for a single game, for it only to exist on Google’s servers rather than on your own PC, seemed a stretch to some. After all the hype, gamers were disappointed. Stadia missed its targets for sales of controllers and monthly active users by hundreds of thousands, according to two people familiar with the matter, who asked not to be identified discussing private information. A Google spokesperson declined to comment for this story.

There’s something deeply embedded in Google’s DNA that makes it great at solving huge (like exabytes of data huge) technical problems, but consistently struggle at creating actual products. If you need to manage lists of data (photos, documents, search results, messages), Google’s got you covered, but good luck getting an actual product that you’re happy holding onto for years from them.

LastPass Free might not be worth using soon

Any time I talk about passwords with people, I always end up recommending password managers. I don’t really expect average computer users to have amazing password practices1 considering just how many different accounts you need for things these days. I’ve been using 1Password for a while, but I’ve been keeping an eye on some of the others (Bitwarden, Dashlane, LastPass, etc) too.

LastPass just recently decided to severely restrict the service’s free tier. Right now, you can sign up for LastPass for free and get access on all your devices. After March 16th, you’ll have to choose between having access on your computers (laptops, desktops, etc) or on your mobile devices (phone, tablet, watch, etc). Full access starts at $3 per month.

From the support page:

As a LastPass Free user, your first login on or after March 16, 2021 will set your active device type. You’ll have three (3) opportunities to switch your active device type and explore what’s right for you. Please note that all of your devices sync automatically, so you’ll never lose access to anything stored in your Vault or be locked out of your account due to these changes, regardless of whether you use computers or mobile devices to access LastPass.

I have no problem with having to pay for the service (1Password has no free tier at all), but springing this kind of change on people who have already been using it feels pretty shitty. It’s clearly not really useful this way since most people with more than one device are probably using one of each of the device types (phone and laptop), so they’re just kicking people off the free service without being direct2 about it.

Most of the people I’m seeing talk about this today are mentioning Bitwarden. It’s free for use on all devices (and has paid plans with more features) and is also open source.

-

It mostly just comes down to length as far as I understand. The longer your password, the harder it is to crack. Sometimes it’s recommended to use passphrases (just put like 4 different words together) instead of passwords if possible. ↩︎

-

Obviously there’s no easy way to tell your customers you gotta start charging more, but if it were up to me I probably would have wanted to announce a restructuring of the pricing tier, eliminating the free tier, and lowering the prices slightly and/or adding more value to the other ones. ↩︎