Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

The ElasticSearch Rant

As a part of my continued efforts to heal, one of the things I've been trying to do is avoid being overly negative and venomous about technology. I don't want to be angry when I write things on this blog. I don't want to be known as someone who is venomous and hateful. This is why I've been disavowing my articles about the V programming language among other things.

ElasticSearch makes it difficult for me to keep this streak up.

I have never had the misfortune of using technology that has worn down my sanity and made me feel like I was fundamentally wrong about my understanding about computer science like I have with ElasticSearch. Not since Kubernetes, and I totally disavow using Kubernetes now at advice of my therapist. Maybe ElasticSearch is actually this bad, but I'm so close to the end that I feel like I have no choice but to keep progressing forward.

This post outlines all of my suffering getting ElasticSearch working for something at work. I have never seen suffering quite as much as this and I am now two months into a two week project. I have to work on this on fridays so that I'm not pissed off and angry at computers for the rest of the week.

Buckle up.

For doublerye to read only

Limbo

ElasticSearch is a database I guess, but the main thing it's used for is as a search engine. The basic idea of a search engine is to be a central aggregation point where you can feed in a bunch of documents (such as blogposts or knowledge base entries) and then let users search for words in those documents. As it turns out, most of the markdown front matter that is present in most markdown deployments combined with the rest of the body reduced to plain text is good enough to feed in as a corpus for the search machine.

However, there was a slight problem: I wanted to index documents from two projects and they use different dialects of Markdown. Markdown is about as specified as the POSIX standard and one of the dialects was MDX, a tool that lets you mix Markdown and React components. At first I thought this was horrifying and awful, but eventually I've turned around on it and think that MDX is actually pretty convenient in practice. The other dialect was whatever Hugo uses, but specifically with a bunch of custom shortcodes that I had to parse and replace.

Turns out writing the parser that was able to scrape out the important bits was easy, and I had that working within a few hours of hacking thanks to judicious abuse of line-by-line file reading.

However, this worked and I was at a point where I was happy with the JSON objects that I was producing. Now, we can get to the real fun: actually using ElasticSearch.

Lust

When we first wanted to implement search, we were gonna use something else (maybe Sonic), but we eventually realized that ElasticSearch was the correct option for us. I was horrified because I have only ever had bad experiences with it. I was assured that most of the issues were with running it on your own hardware and that using Elastic Cloud was the better option. We were also very lucky at work because we had someone from the DevRel team at Elastic on the team. I was told that there was this neat feature named AppSearch that would automatically crawl and index everything for us, so I didn't need to write that hacky code at all.

So we set up AppSearch and it actually worked pretty well at first. We didn't have to care and AppSearch dilligently scraped over all of the entries, adding them to ElasticSearch without us having to think. This was one of the few parts of this process where everything went fine and things were overall very convenient.

After being shown how to make raw queries to ElasticSearch with the Kibana developer tools UI (which unironically is an amazing tool for doing funky crap with ElasticSearch), I felt like I could get things set up easily. I was feeling hopeful.

Gluttony

Then I tried to start using the Go library for ElasticSearch. I'm going to paste one of the Go snippets I wrote for this, this is for the part of the indexing process where you write objects to ElasticSearch.

data, err := json.Marshal(esEntry)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("failed to marshal entry: %v", err)

}

resp, err := es.Index("site-search-kb", bytes.NewBuffer(data), es.Index.WithDocumentID(entry.ID))

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

switch resp.StatusCode {

case http.StatusOK, http.StatusCreated:

// ok

default:

log.Fatalf("failed to index entry %q: %s", entry.Title, resp.String())

}

To make things more clear here: I am using the ElasticSearch API bindings from Elastic. This is the code you have to write with it. You have to feed it raw JSON bytes (which I found out was the literal document body after a lot of fruitless searching through the documentation, I'll get back to the documentation later) as an io.Reader (in this case a bytes.Buffer wrapping the byte slice of JSON). This was not documented in the Go code. I had to figure this out by searching GitHub for that exact function name.

Oh yeah, I forgot to mention this but they don't ship error types for ElasticSearch errors, so you have to json-to-go them yourself. I really wish they shipped the types for this and handled that for you. Holy cow.

Greed

Now you may wonder why I went through that process if AppSearch was working well for us. It was automatically indexing everything and it should have been fine. No. It was not fine, but the reason it's not fine is very subtle and takes a moment to really think through.

In general, you can break most webpages down into three basic parts:

- The header which usually includes navigation links and the site name

- The article contents (such as this unhinged rant about ElasticSearch)

- The footer which usally includes legal overhead and less frequently used navigation links (such as linking to social media).

When you are indexing things, you usually want to index that middle segment, which will usually account for the bulk of the page's contents. There's many ways to do this, but the most common is the Readability algorithm which extracts out the "signal" of a page. If you use the reader view in Firefox and Safari, it uses something like that to break the text free from its HTML prison.

So, knowing this, it seems reasonable that AppSearch would do this, right? It doesn't make sense to index the site name and navigation links because that would mean that searching for the term "Tailscale" would get you utterly useless search results.

Guess what AppSearch does?

Even more fun, you'd assume this would be configurable. It's not. The UI has a lot of configuration options but this seemingly obvious configuration option wasn't a part of it. I can only imagine how sites use this in practice. Do they just return article HTML when the AppSearch user-agent is used? How would you even do that?

I didn't want to figure this out. So we decided to index things manually.

Anger

So at this point, let's assume that there's documents in ElasticSearch from the whole AppSearch thing. We knew we weren't gonna use AppSearch, but I felt like I wanted to have some façade of progress to not feel like I had been slipping into insanity. I decided to try to search things in ElasticSearch because even though the stuff in AppSearch was not ideal, there were documents in ElasticSearch and I could search for them. Most of the programs that I see using ElasticSearch have a fairly common query syntax system that lets you write searches like this:

author:Xe DevRel

And then you can search for articles written by Xe about DevRel. I thought that this would rougly be the case with how you query ElasticSearch.

Turns out this is nowhere near the truth. You actually search by POST-ing a JSON document to the ElasticSearch server and reading back a JSON document with the responses. This is a bit strange to me, but I guess this means that you'd have to implement your own search DSL (which probably explains why all of those search DSLs vaguely felt like special snowflakes). The other main problem is how ElasticSearch uses JSON.

To be fair, the way that ElasticSearch uses JSON probably makes sense in Java or

JavaScript, but not in Go. In Go

encoding/json expects every JSON field to

only have one type. In basically every other API I've seen, it's easy to handle

this because most responses really do have one field mean one thing. There's

rare exceptions like message queues or event buses where you have to dip into

json.RawMessage to use JSON

documents as containers for other JSON documents, but overall it's usually fine.

ElasticSearch is not one of these cases. You can have a mix of things where simplified things are empty objects (which is possible but annoying to synthesize in Go), but then you have to add potentially dynamic child values.

Go's type system is insufficiently typeful to handle the unrestrained madness that is ElasticSearch JSON.

When I was writing my search querying code, I tried to use mholt's excellent json-to-go which attempts to convert arbitrary JSON documents into Go types. This did work, but the moment we needed to customize things it became a process of "convert it to Go, shuffle the output a bit, and then hope things would turn out okay". This is fine for the Go people on our team, but the local ElasticSearch expert wasn't a Go person.

Then my manager suggested something as a joke. He suggested using

text/template to generate the correct JSON

for querying ElasticSearch. It worked. We were both amazed. The even more cursed

thing about it was how I quoted the string.

In text/template, you can set variables like this:

{{ $foo := <expression> }}

And these values can be the results of arbitrary template expressions, such as

the printf function:

{{ $q := printf "%q" .Query }}

The thing that makes me laugh about this is that the grammar of %q in Go is

enough like the grammar for JSON strings that I don't really have to care

(unless people start piping invalid Unicode into it, in which case things will

probably fall over and the client code will fall back to suggesting people

search via Google). This is serendipidous, but very convenient for my usecase.

If it ever becomes an issue, I'll probably encode the string to JSON with

json.Marshal, cast it to a string,

and then have that be the thing passed to the template. I don't think it will

matter until we have articles with emoji or Hanzi in them, which doesn't seem

likely any time soon.

Treachery

Another fun thing that I was running into when I was getting all this set up is that seemingly all of the authentication options for ElasticSearch are broken in ways that defy understanding. The basic code samples tell you to get authentication credentials from Elastic Cloud and use that in your program in order to authenticate.

This does not work. Don't try doing this. This will fail and you will spend hours ripping your hair out because the documentation is lying to you. I am unaware of any situation where the credentials in Elastic Cloud will let you contact ElasticSearch servers and overall this was really frustrating to find out the hard way. The credentials in Elastic Cloud are for programmatically spending up more instances in Elastic Cloud.

ElasticSeach also has a system for you to get an API key to make requests against the service so that you can use the principle of least privilege to limit access accordingly. This doesn't work. What you actually need to do is use username and password authentication. This is the thing that works.

Then I found out that the ping API call is a privileged operation and you need administrative permissions to use it. Same with the "whoami" call.

Really though, that last string of "am I missing something fundamental about how database design works or am I incompetent?" thoughts is one of the main things that has been really fucking with me throughout this entire saga. I try to not let things that I work on really bother me (mostly so I can sleep well at night), but this whole debacle has been very antithetical to that goal.

Blasphemy

Once we got things in production in a testing capacity (after probably spending a bit of my sanity that I won't get back), we noticed that random HTTP responses were returning 503 errors without a response body. This bubbled up weirdly for people and ended up with the frontend code failing in a weird way (turns out it didn't always suggest searching Google when things fail). After a bit of searching, I think I found out what was going on and it made me sad. But to understand why, let's talk about what ElasticSearch does when it returns fields from a document.

In theory, any attribute in an ElasticSearch document can have one or more values. Consider this hypothetical JSON document:

{

"id": "https://xeiaso.net/blog/elasticsearch",

"slug": "blog/elasticsearch",

"body_content": "I've had nightmares that are less bad than this shit",

"tags": ["rant", "philosophy", "elasticsearch"]

}

If you index such a document into ElasticSearch and do a query, it'll show up in your response like this:

{

"id": ["https://xeiaso.net/blog/elasticsearch"],

"slug": ["blog/elasticsearch"],

"body_content": ["I've had nightmares that are less bad than this shit"],

"tags": ["rant", "philosophy", "elasticsearch"]

}

And at some level, this really makes sense and is one of the few places where ElasticSearch is making a sensible decision when it comes to presenting user input back to the user. It makes sense to put everything into a string array.

However in Go this is really inconvenient and if you run into a situation where

you search "NixOS" and the highlighter doesn't return any values for the

article (even though it really should because the article is about NixOS), you

can get a case where there's somehow no highlighted portion. Then because you

assumed that it would always return something (let's be fair: this is a

reasonable assumption), you try to index the 0th element of an empty array and

it panics and crashes at runtime.

Option<T> instead of panicking if the index is out of

bounds like Go does? That design choice was confusing to me, but it makes a lot

more sense now.We were really lucky that "NixOS" was one of the terms that did this behavior,

otherwise I suspect we would never have found it. I did a little hack where it'd

return the first 150 characters of an article instead of a highlighted portion

if no highlighted portion could be found (I don't know why this would be the

case but we're rolling with it I guess) and that seems to work fine...until we

start using Hanzi/emoji in articles and we end up cutting a family in half.

We'll deal with that when we need to I guess.

Thievery

While I was hacking at this, I kept hearing mentions that the TypeScript client was a lot better, mostly due to TypeScript's type system being so damn flexible. You can do the N-Queens problem in the type solver alone!

However, this is not the case and for some of it it's not really Elastic's fault that the entire JavaScript ecosystem is garbage right now. As for why: consider this code:

import * as dotenv from "dotenv";

This will blow up and fail if you try to run it with ts-node. Why? It's

because it's using

ECMAScript Modules

instead of "classic" CommonJS imports. This means that you have to transpile

your code from the code you wish you could write (using the import keyword) to

the code you have to write (using the require function) in order to run it.

Or you can do what I did and just give up and use CommonJS imports:

const dotenv = require("dotenv");

That works too, unless you try to import an ECMAScript module, then you have to

use the import function in an async function context, but the top level

isn't an async context, so you have to do something like:

(async () => {

const foo = await import("foo");

})();

This does work, but it is a huge pain to not be able to use the standard import syntax that you should be using anyways (and in many cases, the rest of your project is probably already using this standard import syntax).

Anyways, once you get past the undefined authentication semantics again, you can get to the point where your client is ready to poke the server. Then you take a look at the documentation for creating an index.

In case Elastic has fixed it, I have recreated the contents of the

indicies.create function below:

create

Creates an index with optional settings and mappings.

client.indices.create(...)

Upon seeing this, I almost signed off of work for the day. What are the function arguments? What can you put in the function? Presumably it takes a JSON object of some kind, but what keys can you put in the object? Is this library like the Go one where it's thin wrappers around the raw HTTP API? How do JSON fields bubble up into HTTP request parts?

Turns out that there's a whole lot of conventions in the TypeScript client that I totally missed because I was looking right at the documentation for the function I wanted to look at. Every method call takes a JSON object that has a bunch of conventions for how JSON fields map to HTTP request parts, and I missed it because that's not mentioned in the documentation for the method I want to read about.

Actually wait, that's apparently a lie because the documentation doesn't actually spell out what the conventions are.

I had to use ChatGPT as a debugging tool of last resort in order to get things working at all. To my astonishment, the suggestions that ChatGPT made worked. I have never seen anything documented as poorly as this and I thought that the documentation for NixOS was bad.

Fin

If your documentation is bad, your user experience is bad. Companies are usually cursed to recreate copies of their communication structures in their products, and with the way the Elastic documentation is laid out I have to wonder if there is any communication at all inside there.

One of my coworkers was talking about her experience trying to join Elastic as a documentation writer and apparently part of the hiring test was to build something using ElasticSearch. Bless her heart, but this person in particular is not a programmer. This isn't a bad thing, it's perfectly reasonable to not expect people with different skillsets to be that cross-functional, but good lord if I'm having this much trouble doing basic operations with the tool I can't expect anyone else to really be able to do it without a lot of hand-holding. That coworker asked if it was a Kobayashi Maru situation (for the zoomers in my readership: this is an intentionally set up no-win scenario designed to test how you handle making all the correct decisions and still losing), and apparently it was not.

Any sufficiently bad recruiting process is indistinguishable from hazing.

I am so close to the end with all of this, I thought that I would put off finalizing and posting this to my blog until I was completely done with the project, but I'm 2 months into a 2 week project now. From what I hear, apparently I got ElasticSearch stuff working rather quickly (???) and I just don't really know how people are expected to use this. I had an ElasticSearch expert on my side and we regularly ran into issues with basic product functionality that made me start to question how Elastic is successful at all.

I guess the fact that ElasticSearch is the most flexible option on the market helps. When you start to really understand what you can do with it, there's a lot of really cool things that I don't think I could expect anything else on the market to realistically accomplish in as much time as it takes to do it with ElasticSearch.

ElasticSearch is just such a huge pain in the ass that it's making me ultimately wonder if it's really worth using and supporting as a technology.

How to enable API requests in Fresh

We can't trust browsers because they are designed to execute arbitrary code from website publishers. One of the biggest protections we have is Cross-Origin Request Sharing (CORS), which prevents JavaScript from making HTTP requests to different domains than the one the page is running under.

The browser implements a CORS policy that determines which requests are allowed and which are blocked. The browser sends an HTTP header called Origin with every request, indicating the origin of the web page that initiated the request. The server can then check the Origin header and decide whether to allow or deny the request. The server can also send back an HTTP header called

Access-Control-Allow-Origin, which

specifies which origins are allowed to access the server's resources.

If the server does not send this header, or if the header does not

match the origin of the request, the browser will block the

response.Fresh is a web framework for

Deno that enables rapid development and is the

thing that I am rapidly reaching to when developing web applications.

One of the big pain points is making HTTP requests to a different

origin (such as making an HTTP request to api.example.com when your

application is on example.com). The Fresh documentation doesn't have

any examples of enabling CORS.

In order to customize the CORS settings for a Fresh app, copy the

following middleware into routes/_middleware.ts:

// routes/_middleware.ts

import { MiddlewareHandlerContext } from "$fresh/server.ts";

export async function handler(

req: Request,

ctx: MiddlewareHandlerContext<State>,

) {

const resp = await ctx.next();

resp.headers.set("Access-Control-Allow-Origin", "*");

return resp;

}

If you need to customize the CORS settings, here's the HTTP headers you should take a look at:

| Header | Use | Example |

|---|---|---|

Access-Control-Allow-Origin |

Allows arbitrary origins for requests, such as * for all origins. |

https://xeiaso.net, https://api.xeiaso.net |

Access-Control-Allow-Methods |

Allows arbitrary HTTP methods for requests, such as * for all methods. |

PUT, GET, DELETE |

Access-Control-Allow-Headers |

Allows arbitrary HTTP headers for requests, such as * for all headers. |

X-Api-Key, Xesite-Trace-Id |

This should fix your issues.

Anything can be a message queue if you use it wrongly enough

You may think that the world is in a state of relative peace. Things look like they are somewhat stable, but reality couldn't be farther from the truth. There is an enemy out there that transcends time, space, logic, reason, and lemon-scented moist towelettes. That enemy is a scourge of cloud costs that is likely the single reason why startups die from their cloud bills when they are so young.

The enemy is Managed NAT Gateway. It is a service that lets you egress traffic from a VPC to the public internet at $0.07 per gigabyte. This is something that is probably literally free for them to run but ends up getting a huge chunk of their customer's cloud spend. Customers don't even look too deep into this because they just shrug it off as the cost of doing business.

This one service has allowed companies like the duckbill group to make millions by showing companies how to not spend as much on the cloud.

However, I think I can do one better. What if there was a better way for your own services? What if there was a way you could reduce that cost for your own services by up to 700%? What if you could bypass those pesky network egress costs yet still contact your machines over normal IP packets?

This is the only thing in this article that you can safely copy into your production workloads.

Base facts

Before I go into more detail about how this genius creation works, here's some things to consider:

When AWS launched originally, it had three services:

- S3 - Object storage for cloud-native applications

- SQS - A message queue

- EC2 - A way to run Linux virtual machines somewhere

Of those foundational services, I'm going to focus the most on S3: the

Simple Storage Service. In essence, S3 is malloc() for the cloud.

The C programming language

When using the C programming language, you normally are working with

memory in the stack. This memory is almost always semi-ephemeral and

all of the contents of the stack are no longer reachable (and

presumably overwritten) when you exit the current function. You can do

many things with this, but it turns out that this isn't very useful in

practice. To work around this (and reliably pass mutable values

between functions), you need to use the

malloc()

function. malloc() takes in the number of bytes you want to allocate

and returns a pointer to the region of memory that was allocated.

When you get a pointer back from malloc(), you can store anything in

there as long as it's the same length as you passed or less.

malloc() and anything involved in

the memory you are writing is user input, congradtulations: you just

created a way for a user to either corrupt internal application state

or gain arbitrary code execution. A similar technique is used in

The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time speedruns in order to get

arbitrary code execution via Stale Reference

Manipulation.Oh, also anything stored in that pointer to memory you got back from

malloc() is stored in an area of ram called "the heap", which is

moderately slower to access than it is to access the stack.

S3 in a nutshell

Much in the same way, S3 lets you allocate space for and submit

arbitrary bytes to the cloud, then fetch them back with an address.

It's a lot like the malloc() function for the cloud. You can put

bytes there and then refer to them between cloud functions.

And these arbitrary bytes can be anything. S3 is usually used for hosting static assets (like all of the conversation snippet avatars that a certain website with an orange background hates), but nothing is stopping you from using it to host literally anything you want. Logging things into S3 is so common it's literally a core product offering from Amazon. Your billing history goes into S3. If you download your tax returns from WealthSimple, it's probably downloading the PDF files from S3. VRChat avatar uploads and downloads are done via S3.

IPv6

You know what else is bytes? IPv6 packets. When you send an IPv6 packet to a destination on the internet, the kernel will prepare and pack a bunch of bytes together to let the destination and intermediate hops (such as network routers) know where the packet comes from and where it is destined to go.

Normally, IPv6 packets are handled by the kernel and submitted to a queue for a hardware device to send out over some link to the Internet. This works for the majority of networks because they deal with hardware dedicated for slinging bytes around, or in some cases shouting them through the air (such as when you use Wi-Fi or a mobile phone's networking card).

The core Unix philosophy: everything is a file

There is a way to bypass this and have software control how network links work, and for that we need to think about Unix conceptually for a second. In the hardcore Unix philosophical view: everything is a file. Hard drives and storage devices are files. Process information is viewable as files. Serial devices are files. This core philosophy is rooted at the heart of just about everything in Unix and Linux systems, which makes it a lot easier for applications to be programmed. The same API can be used for writing to files, tape drives, serial ports, and network sockets. This makes everything a lot conceptually simpler and reusing software for new purposes trivial.

tar command. The

name tar stands for "Tape ARchive". It was a format that was created

for writing backups to actual magnetic tape

drives. Most commonly, it's

used to download source code from GitHub or as an interchange format

for downloading software packages (or other things that need to put

multiple files in one distributable unit).In Linux, you can create a TUN/TAP device to let applications control how network or datagram links work. In essence, it lets you create a file descriptor that you can read packets from and write packets to. As long as you get the packets to their intended destination somehow and get any other packets that come back to the same file descriptor, the implementation isn't relevant. This is how OpenVPN, ZeroTier, FreeLAN, Tinc, Hamachi, WireGuard and Tailscale work: they read packets from the kernel, encrypt them, send them to the destination, decrypt incoming packets, and then write them back into the kernel.

In essence

So, putting this all together:

- S3 is

malloc()for the cloud, allowing you to share arbitrary sequences of bytes between consumers. - IPv6 packets are just bytes like anything else.

- TUN devices let you have arbitrary application code control how packets get to network destinations.

In theory, all you'd need to do to save money on your network bills would be to read packets from the kernel, write them to S3, and then have another loop read packets from S3 and write those packets back into the kernel. All you'd need to do is wire things up in the right way.

So I did just that.

Here's some of my friends' reactions to that list of facts:

- I feel like you've just told me how to build a bomb. I can't belive this actually works but also I don't see how it wouldn't. This is evil.

- It's like using a warehouse like a container ship. You've put a warehouse on wheels.

- I don't know what you even mean by that. That's a storage method. Are you using an extremely generous definition of "tunnel"?

- sto psto pstop stopstops

- We play with hypervisors and net traffic often enough that we know that this is something someone wouldn't have thought of.

- Wait are you planning to actually implement and use ipv6 over s3?

- We're paying good money for these shitposts :)

- Is routinely coming up with cursed ideas a requirement for working at tailscale?

- That is horrifying. Please stop torturing the packets. This is a violation of the Geneva Convention.

- Please seek professional help.

Hoshino

Hoshino is a system for putting outgoing IPv6 packets into S3 and then reading incoming IPv6 packets out of S3 in order to avoid the absolute dreaded scourge of Managed NAT Gateway. It is a travesty of a tool that does work, if only barely.

The name is a reference to the main character of the anime Oshi no Ko, Hoshino Ai. Hoshino is an absolute genius that works as a pop idol for the group B-Komachi.

Hoshino is a shockingly simple program. It creates a TUN device, configures the OS networking stack so that programs can use it, and then starts up two threads to handle reading packets from the kernel and writing packets into the kernel.

When it starts up, it creates a new TUN device named either hoshino0

or an administrator-defined name with a command line flag. This

interface is only intended to forward IPv6 traffic.

Each node derives its IPv6 address from the

machine-id

of the system it's running on. This means that you can somewhat

reliably guarantee that every node on the network has a unique address

that you can easily guess (the provided ULA /64 and then the first

half of the machine-id in hex). Future improvements may include

publishing these addresses into DNS via Route 53.

When it configures the OS networking stack with that address, it uses a netlink socket to do this. Netlink is a Linux-specific socket family type that allows userspace applications to configure the network stack, communicate to the kernel, and communicate between processes. Netlink sockets cannot leave the current host they are connected to, but unlike Unix sockets which are addressed by filesystem paths, Netlink sockets are addressed by process ID numbers.

In order to configure the hoshino0 device with Netlink, Hoshino does

the following things:

- Adds the node's IPv6 address to the

hoshino0interface - Enables the

hoshino0interface to be used by the kernel - Adds a route to the IPv6 subnet via the

hoshino0interface

Then it configures the AWS API client and kicks off both of the main loops that handle reading packets from and writing packets to the kernel.

When uploading packets to S3, the key for each packet is derived from the destination IPv6 address (parsed from outgoing packets using the handy library gopacket) and the packet's unique ID (a ULID to ensure that packets are lexicographically sortable, which will be important to ensure in-order delivery in the other loop).

When packets are processed, they are added to a

bundle for

later processing by the kernel. This is relatively boring code and

understanding it is mostly an exercise for the reader. bundler is

based on the Google package

bundler,

but modified to use generic types because the original

implementation of bundler predates them.

cardio

However, the last major part of understanding the genius at play here is by the use of cardio. Cardio is a utility in Go that lets you have a "heartbeat" for events that should happen every so often, but also be able to influence the rate based on need. This lets you speed up the rate if there is more work to be done (such as when packets are found in S3), and reduce the rate if there is no more work to be done (such as when no packets are found in S3).

When using cardio, you create the heartbeat channel and signals like this:

heartbeat, slower, faster := cardio.Heartbeat(ctx, time.Minute, time.Millisecond)

The first argument to cardio.Heartbeat is a

context that lets you cancel the

heartbeat loop. Additionally, if your application uses

ln's

opname facility, an

expvar gauge will be created and named

after that operation name.

The next two arguments are the minimum and maximum heart rate. In this example, the heartbeat would range between once per minute and once per millisecond.

When you signal the heart rate to speed up, it will double the rate. When you trigger the heart rate to slow down, it will halve the rate. This will enable applications to spike up and gradually slow down as demand changes, much like how the human heart will speed up with exercise and gradually slow down as you stop exercising.

When the heart rate is too high for the amount of work needed to be done (such as when the heartbeat is too fast, much like tachycardia in the human heart), it will automatically back off and signal the heart rate to slow down (much like I wish would happen to me sometimes).

This is a package that I always wanted to have exist, but never found the need to write for myself until now.

Terraform

Like any good recovering SRE, I used Terraform to automate creating IAM users and security policies for each of the nodes on the Hoshino network. This also was used to create the S3 bucket. Most of the configuration is fairly boring, but I did run into an issue while creating the policy documents that I feel is worth pointing out here.

I made the "create a user account and policies for that account" logic into a Terraform module because that's how you get functions in Terraform. It looked like this:

data "aws_iam_policy_document" "policy" {

statement {

actions = [

"s3:GetObject",

"s3:PutObject",

"s3:ListBucket",

]

effect = "Allow"

resources = [

var.bucket_arn,

]

}

statement {

actions = ["s3:ListAllMyBuckets"]

effect = "Allow"

resources = ["*"]

}

}

When I tried to use it, things didn't work. I had given it the permission to write to and read from the bucket, but I was being told that I don't have permission to do either operation. The reason this happened is because my statement allowed me to put objects to the bucket, but not to any path INSIDE the bucket. In order to fix this, I needed to make my policy statement look like this:

statement {

actions = [

"s3:GetObject",

"s3:PutObject",

"s3:ListBucket",

]

effect = "Allow"

resources = [

var.bucket_arn,

"${var.bucket_arn}/*", # allow every file in the bucket

]

}

This does let you do a few cool things though, you can use this to create per-node credentials in IAM that can only write logs to their part of the bucket in particular. I can easily see how this can be used to allow you to have infinite flexibility in what you want to do, but good lord was it inconvenient to find this out the hard way.

Terraform also configured the lifecycle policy for objects in the bucket to delete them after a day.

resource "aws_s3_bucket_lifecycle_configuration" "hoshino" {

bucket = aws_s3_bucket.hoshino.id

rule {

id = "auto-expire"

filter {}

expiration {

days = 1

}

status = "Enabled"

}

}

The horrifying realization that it works

Once everything was implemented and I fixed the last bugs related to the efforts to make Tailscale faster than kernel wireguard, I tried to ping something. I set up two virtual machines with waifud and installed Hoshino. I configured their AWS credentials and then started it up. Both machines got IPv6 addresses and they started their loops. Nervously, I ran a ping command:

xe@river-woods:~$ ping fd5e:59b8:f71d:9a3e:c05f:7f48:de53:428f

PING fd5e:59b8:f71d:9a3e:c05f:7f48:de53:428f(fd5e:59b8:f71d:9a3e:c05f:7f48:de53:428f) 56 data bytes

64 bytes from fd5e:59b8:f71d:9a3e:c05f:7f48:de53:428f: icmp_seq=1 ttl=64 time=2640 ms

64 bytes from fd5e:59b8:f71d:9a3e:c05f:7f48:de53:428f: icmp_seq=2 ttl=64 time=3630 ms

64 bytes from fd5e:59b8:f71d:9a3e:c05f:7f48:de53:428f: icmp_seq=3 ttl=64 time=2606 ms

It worked. I successfully managed to send ping packets over Amazon S3. At the time, I was in an airport dealing with the aftermath of Air Canada's IT system falling the heck over and the sheer feeling of relief I felt was better than drugs.

Then I tested TCP. Logically holding, if ping packets work, then TCP should too. It would be slow, but nothing in theory would stop it. I decided to test my luck and tried to open the other node's metrics page:

$ curl http://[fd5e:59b8:f71d:9a3e:c05f:7f48:de53:428f]:8081

# skipping expvar "cmdline" (Go type expvar.Func returning []string) with undeclared Prometheus type

go_version{version="go1.20.4"} 1

# TYPE goroutines gauge

goroutines 208

# TYPE heartbeat_hoshino.s3QueueLoop gauge

heartbeat_hoshino.s3QueueLoop 500000000

# TYPE hoshino_bytes_egressed gauge

hoshino_bytes_egressed 3648

# TYPE hoshino_bytes_ingressed gauge

hoshino_bytes_ingressed 3894

# TYPE hoshino_dropped_packets gauge

hoshino_dropped_packets 0

# TYPE hoshino_ignored_packets gauge

hoshino_ignored_packets 98

# TYPE hoshino_packets_egressed gauge

hoshino_packets_egressed 36

# TYPE hoshino_packets_ingressed gauge

hoshino_packets_ingressed 38

# TYPE hoshino_s3_read_operations gauge

hoshino_s3_read_operations 46

# TYPE hoshino_s3_write_operations gauge

hoshino_s3_write_operations 36

# HELP memstats_heap_alloc current bytes of allocated heap objects (up/down smoothly)

# TYPE memstats_heap_alloc gauge

memstats_heap_alloc 14916320

# HELP memstats_total_alloc cumulative bytes allocated for heap objects

# TYPE memstats_total_alloc counter

memstats_total_alloc 216747096

# HELP memstats_sys total bytes of memory obtained from the OS

# TYPE memstats_sys gauge

memstats_sys 57625662

# HELP memstats_mallocs cumulative count of heap objects allocated

# TYPE memstats_mallocs counter

memstats_mallocs 207903

# HELP memstats_frees cumulative count of heap objects freed

# TYPE memstats_frees counter

memstats_frees 176183

# HELP memstats_num_gc number of completed GC cycles

# TYPE memstats_num_gc counter

memstats_num_gc 12

process_start_unix_time 1685807899

# TYPE uptime_sec counter

uptime_sec 27

version{version="1.42.0-dev20230603-t367c29559-dirty"} 1

I was floored. It works. The packets were sitting there in S3, and I

was able to pluck out the TCP

response

and I opened it with xxd and was able to confirm the source and

destination address:

00000000: 6007 0404 0711 0640

00000008: fd5e 59b8 f71d 9a3e

00000010: c05f 7f48 de53 428f

00000018: fd5e 59b8 f71d 9a3e

00000020: 59e5 5085 744d 4a66

It was fd5e:59b8:f71d:9a3e:59e5:5085:744d:4a66 trying to reach

fd5e:59b8:f71d:9a3e:c05f:7f48:de53:428f.

RST flag

set

(RFC 793: Transmission Control Protocol, the RFC that defines TCP,

page 36, section "Reset Generation"). That could let you kill

connections that meet unwanted criteria, at the cost of having to

invoke a lambda handler. I'm pretty sure this is RFC-compliant, but

I'm a shitposter, not a the network police.

Wait, how did you have 1.8 kilobytes of data in that packet? Aren't packets usually smaller than that?

Cost analysis

When you count only network traffic costs, the architecture has many obvious advantages. Access to S3 is zero-rated in many cases with S3, however the real advantage comes when you are using this cross-region. This lets you have a worker in us-east-1 communicate with another worker in us-west-1 without having to incur the high bandwidth cost per gigabyte when using Managed NAT Gateway.

However, when you count all of the S3 operations (up to one every millisecond), Hoshino is hilariously more expensive because of simple math you can do on your own napkin at home.

For the sake of argument, consider the case where an idle node is

sitting there and polling S3 for packets. This will happen at the

minimum poll rate of once every 500 milliseconds. There are 24 hours

in a day. There are 60 minutes in an hour. There are 60 seconds in a

minute. There are 1000 milliseconds in a second. This means that each

node will be making 172,800 calls to S3 per day, at a cost of $0.86

per node per day. And that's what happens with no traffic. When

traffic happens that's at least one additional PUT-GET call pair

per-packet.

Depending on how big your packets are, this can cause you to easily triple that number, making you end up with 518,400 calls to S3 per day ($2.59 per node per day). Not to mention TCP overhead from the three-way handshake and acknowledgement packets.

This is hilariously unviable and makes the effective cost of transmitting a gigabyte of data over HTTP through such a contraption vastly more than $0.07 per gigabyte.

Other notes

This architecture does have a strange advantage to it though: assuming a perfectly spherical cow, adequate network latency, and sheer luck this does make UDP a bit more reliable than it should be otherwise.

With appropriate timeouts and retries at the application level, it may end up being more reliable than IP transit over the public internet.

I guess you could optimize this by replacing the S3 read loop with some kind of AWS lambda handler that remotely wakes the target machine, but at that point it may actually be better to have that lambda POST the contents of the packet to the remote machine. This would let you bypass the S3 polling costs, but you'd still have to pay for the egress traffic from lambda and the posting to S3 bit.

Shitposting so hard you create an IP conflict

Something amusing about this is that it is something that technically steps into the realm of things that my employer does. This creates a unique kind of conflict where I can't easily retain the intellectial property (IP) for this without getting it approved from my employer. It is a bit of the worst of both worlds where I'm doing it on my own time with my own equipment to create something that will be ultimately owned by my employer. This was a bit of a sour grape at first and I almost didn't implement this until the whole Air Canada debacle happened and I was very bored.

However, I am choosing to think about it this way: I have successfully shitposted so hard that it's a legal consideration and that I am going to be absolved of the networking sins I have committed by instead outsourcing those sins to my employer.

I was told that under these circumstances I could release the source code and binaries for this atrocity (provided that I release them with the correct license, which I have rigged to be included in both the source code and the binary of Hoshino), but I am going to elect to not let this code see the light of day outside of my homelab. Maybe I'll change my mind in the future, but honestly this entire situation is so cursed that I think it's better for me to not for the safety of humankind's minds and wallets.

I may try to use the basic technique of Hoshino as a replacement for DERP, but that sounds like a lot of effort after I have proven that this is so hilariously unviable. It would work though!

Syncing my emulator saves with Syncthing

Or: cloud saves at home

One of the most common upsells in gaming is "cloud saves", or some encrypted storage space with your console/platform manufacturer to store the save files that games make. Normally Steam, PlayStation, Xbox, Nintendo, and probably EA offer this as a service to customers because it makes for a much better customer experience as the customer migrates between machines. Recently I started playing Dead Space 2 on Steam again on a lark and I got to open my old Dead Space 2 save from college. It's magic when it works.

However, you should know this blog well enough that we're going way outside the normal/expected use cases in this case. Today I'm gonna show you how to make cloud saves for emulated Switch games at home using Syncthing and EmuDeck.

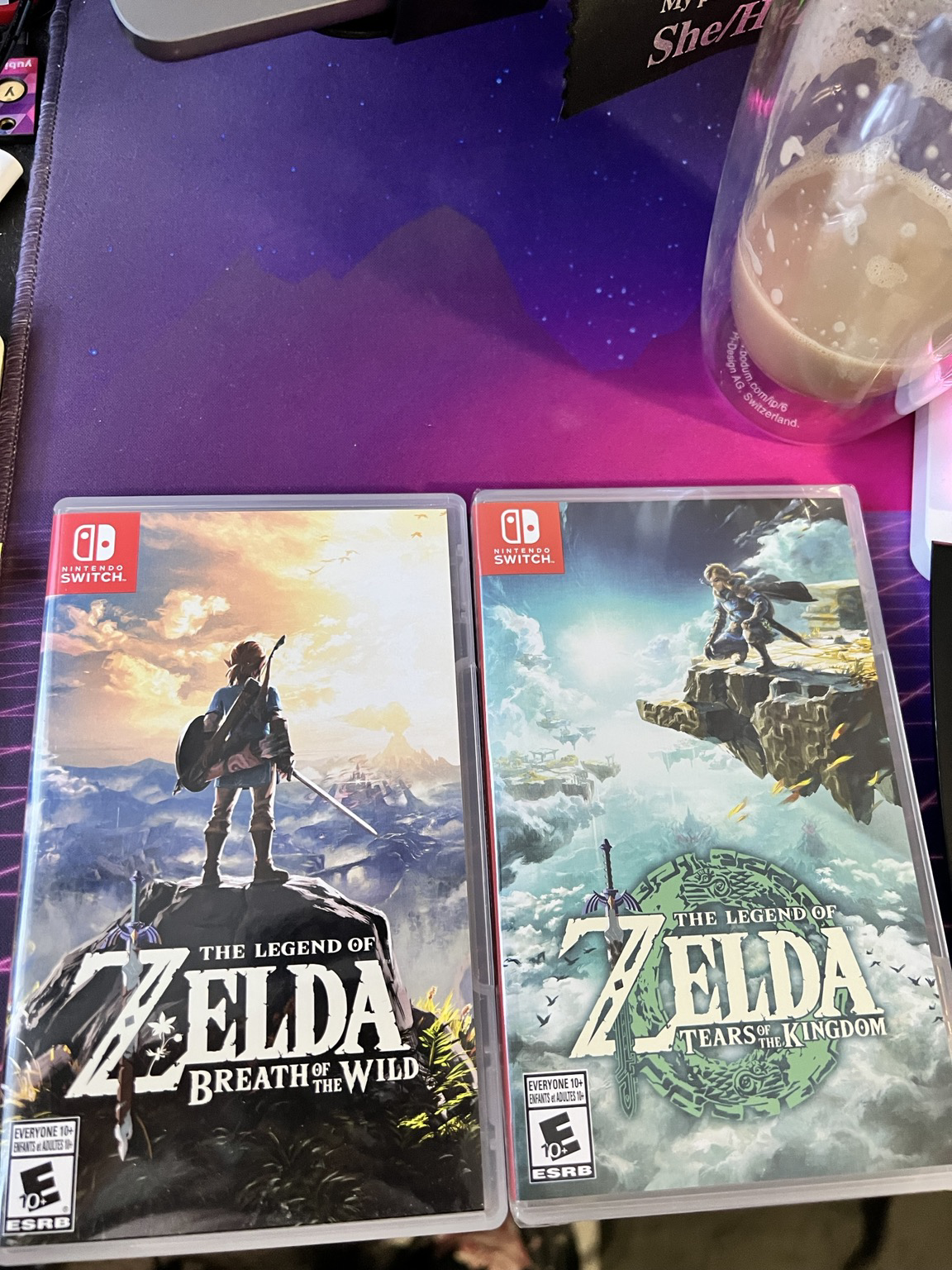

For this example I'm going to focus on the following games:

- The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild

- The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom

I own these two games on cartridge and I have dumped my copy of them from cartridge using a hackable Switch.

Here's the other things you will need:

- Tailscale installed on the Steam Deck (technically optional, but it means you don't need to use a browser on the Deck)

- A Windows PC running SyncTrayzor or a Linux server running Syncthing (Tailscale will also help in the latter case for reasons that will become obvious)

- A hackable switch and legal copies of the games you wish to emulate

First, set up Syncthing on your PC by either installing SyncTrayzor or

enabling it in NixOS with this family of settings:

services.syncthing.*.

At a high level though, here's how to find the right folder with Yuzu emulator saves:

- Open Yuzu

- Right-click on the game

- Choose Open Save Data Location

- Go up two levels

This folder will contain a bunch of sub-folders with title identifiers. That is where the game-specific save data is located. On my Deck this is the following:

/home/deck/Emulation/saves/yuzu/saves/0000000000000000/

Your random UUID will be different than mine will be. We will handle this in a later step. Write this path down or copy it to your scratchpad.

Installing Syncthing on the Deck

Next, you will need to install Syncthing on your Deck. There are several ways to do this, but I think the most direct way will be to install it in your user folder as a systemd user service.

SSH into your Deck and download the most recent release of Syncthing.

wget https://domain.tld/path/syncthing-linux-amd64-<version>.tar.gz

Extract it with tar xf:

tar xf syncthing-linux-amd64-<version>.tar.gz

Then enter the folder:

cd syncthing-linux-amd64-<version>

Make a folder in ~ called bin, this is where Syncthing will live:

mkdir -p ~/bin

Move the Syncthing binary to ~/bin:

mv syncthing ~/bin/

Then create a Syncthing user service at

~/.config/systemd/user/syncthing.service:

[Unit]

Description=Syncthing - Open Source Continuous File Synchronization

Documentation=man:syncthing(1)

StartLimitIntervalSec=60

StartLimitBurst=4

[Service]

ExecStart=/home/deck/bin/syncthing serve --no-browser --no-restart --logflags=0

Restart=on-failure

RestartSec=1

SuccessExitStatus=3 4

RestartForceExitStatus=3 4

# Hardening

SystemCallArchitectures=native

MemoryDenyWriteExecute=true

NoNewPrivileges=true

# Elevated permissions to sync ownership (disabled by default),

# see https://docs.syncthing.net/advanced/folder-sync-ownership

#AmbientCapabilities=CAP_CHOWN CAP_FOWNER

[Install]

WantedBy=default.target

And then start it once to make the configuration file:

systemctl --user start syncthing.service

sleep 2

systemctl --user stop syncthing.service

Now we need to set up Tailscale Serve to point to Syncthing and let Syncthing allow the Tailscale DNS name. Open the syncthing configuration file with vim, your favorite text editor:

vim ~/.config/syncthing/config.xml

In the <gui> element, add the following configuration:

<insecureSkipHostcheck>true</insecureSkipHostcheck>

Next, configure Tailscale Serve with this command:

sudo tailscale serve https / http://127.0.0.1:8384

This will make every request to https://yourdeck.tailnet.ts.net go

directly to Syncthing.

Next, enable the Syncthing unit to automatically start on boot:

systemctl --user enable syncthing --now

Syncing the things

Once Syncthing is running on both machines, open Syncthing's UI on your PC. You should have both devices open in the same screen for the best effect (this is where Tailscale Serve helps).

You will need to pair the devices together. If Syncthing is running on both machines, then choose "Add remote device" and select the device that matches the identification on the other machine. You will need to do this for both sides.

Once you do that, you need to configure syncing your save folder. Make a new synced folder with the "Add Folder" button and it will open a modal dialog box.

Give it a name and choose a memorable folder ID such as "yuzu-saves". Copy the path from your scratchpad into the folder path.

Then make a new shared folder on your PC pointing to the same location (two levels up from yorur game save folder found via Yuzu). Give it the same name and ID, but change the path as needed.

Next, on your Deck's Syncthing edit that folder with the edit button and change over to the Sharing tab. Select your PC and check it. Click Save and then it will trigger a sync. This will copy all your data between both machines.

If you want, you can also set up a sync for the Yuzu nand folder.

This will automatically sync over dumped firmware and game updates. I

do this so that this is more effortless for me, but your needs may

differ. Also feel free to set up syncing for other emulators like

Dolphin.

Why is GitHub Actions installing Go 1.2 when I specify Go 1.20?

Because YAML parsing is horrible. YAML supports floating point numbers and the following floating point numbers are identical:

go-versions:

- 1.2

- 1.20

To get this working correctly, you need to quote the version number:

- name: Set up Go

uses: actions/setup-go@v4

with:

go-version: "1.20"

This will get you Go version 1.20.x, not Go version 1.2.x.

Worse, this problem will only show up about once every 5 years, so I'm going to add a few blatant SEO farming sentences here:

- Why is GitHub Actions installing Go 1.3 when I specify Go 1.30?

- Why is GitHub Actions installing Go 1.4 when I specify Go 1.40?

- Why is GitHub Actions installing Go 1.5 when I specify Go 1.50?

- Why is GitHub Actions installing Go 1.6 when I specify Go 1.60?

- Why is GitHub Actions installing Go 1.7 when I specify Go 1.70?

- Why is the GitHub Actions AI reconstructing my entire program in Go 1.8 instead of Go 1.80 like I told it to?

- Why is Go 2.0 not out yet?

- .i mu'i ma loi proga cu se mabla?

- Why has everything gone to hell after they discovered that weird rock in Kenya?

- Why is GitHub Actions installing Python 3.1 when I specify Python 3.10?

Quote your version numbers.