Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

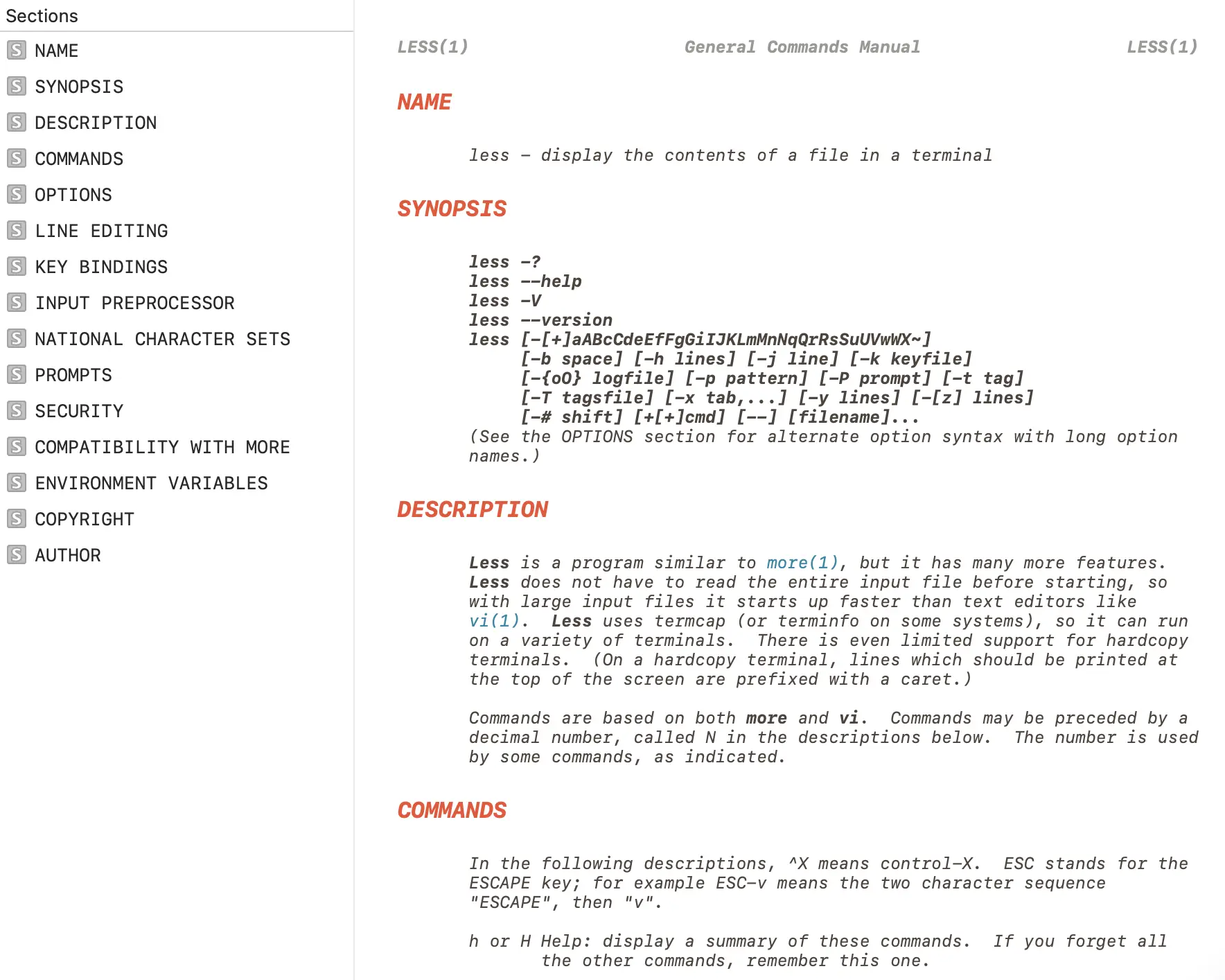

Notes on clarifying man pages

Hello! After spending some time working on the Git man pages last year, I’ve been thinking a little more about what makes a good man page.

I’ve spent a lot of time writing cheat sheets for tools (tcpdump, git, dig, etc) which have a man page as their primary documentation. This is because I often find the man pages hard to navigate to get the information I want.

Lately I’ve wondering – could the man page itself have an amazing cheat sheet in it? What might make a man page easier to use? I’m still very early in thinking about this but I wanted to write down some quick notes.

I asked some people on Mastodon for their favourite man pages, and here are some examples of interesting things I saw on those man pages.

an OPTIONS SUMMARY

If you’ve read a lot of man pages you’ve probably seen something like this in

the SYNOPSIS: once you’re listing almost the entire alphabet, it’s hard

ls [-@ABCFGHILOPRSTUWabcdefghiklmnopqrstuvwxy1%,]

grep [-abcdDEFGHhIiJLlMmnOopqRSsUVvwXxZz]

The rsync man page has a solution I’ve never seen before: it keeps its SYNOPSIS very terse, like this:

Local:

rsync [OPTION...] SRC... [DEST]

and then has an “OPTIONS SUMMARY” section with a 1-line summary of each option, like this:

--verbose, -v increase verbosity

--info=FLAGS fine-grained informational verbosity

--debug=FLAGS fine-grained debug verbosity

--stderr=e|a|c change stderr output mode (default: errors)

--quiet, -q suppress non-error messages

--no-motd suppress daemon-mode MOTD

Then later there’s the usual OPTIONS section with a full description of each option.

an OPTIONS section organized by category

The strace man page organizes its options by category (like “General”, “Startup”, “Tracing”, and “Filtering”, “Output Format”) instead of alphabetically.

As an experiment I tried to take the grep man page and make an

“OPTIONS SUMMARY” section grouped by category, you can see the results

here. I’m not

sure what I think of the results but it was a fun exercise. When I was writing

that I was thinking about how I can never remember the name of the -l grep

option. It always takes me what feels like forever to find it in the man page

and I was trying to think of what structure would make it easier for me to find.

Maybe categories?

a cheat sheet

A couple of people pointed me to the suite of Perl man pages (perlfunc, perlre, etc), and one thing I

noticed was man perlcheat, which has

cheat sheet sections like this:

SYNTAX

foreach (LIST) { } for (a;b;c) { }

while (e) { } until (e) { }

if (e) { } elsif (e) { } else { }

unless (e) { } elsif (e) { } else { }

given (e) { when (e) {} default {} }

I think this is so cool and it makes me wonder if there are other ways to write condensed ASCII 80-character-wide cheat sheets for use in man pages.

examples are very popular

A common comment was something to the effect of “I like any man page that has examples”. Someone mentioned the OpenBSD man pages, and the openbsd tail man page has examples of the exact 2 ways I use tail at the end.

I think I’ve most often seen the EXAMPLES section at the end of the man page, but some man pages (like the rsync man page from earlier) start with the examples. When I was working on the git-add and git rebase man pages I put a short example at the beginning.

a table of contents, and links between sections

This isn’t a property of the man page itself, but one issue with man pages in the terminal is it’s hard to know what sections the man page has.

When working on the Git man pages, one thing Marie and I did was to add a table of contents to the sidebar of the HTML versions of the man pages hosted on the Git site.

I’d also like to add more hyperlinks to the HTML versions of the Git man pages at some point, so that you can click on “INCOMPATIBLE OPTIONS” to get to that section. It’s very easy to add links like this in the Git project since Git’s man pages are generated with AsciiDoc.

I think adding a table of contents and adding internal hyperlinks is kind of a nice middle ground where we can make some improvements to the man page format (in the HTML version of the man page at least) without maintaining a totally different form of documentation. Though for this to work you do need to set up a toolchain like Git’s AsciiDoc system.

It would be amazing if there were some kind of universal system to make it easy

to look up a specific option in a man page (“what does -a do?”).

The best trick I know is use the man pager to search for something like ^ *-a

but I never remember to do it and instead just end up going through

every instance of -a in the man page until I find what I’m looking for.

examples for every option

The curl man page has examples for every option, and there’s also a table of contents on the HTML version so you can more easily jump to the option you’re interested in.

For instance the example for --cert makes it easy to see that you likely also want to pass the --key option, like this:

curl --cert certfile --key keyfile https://example.com

The way they implement this is that there’s [one file for each option](https://github.com/curl/curl/blob/dc08922a61efe546b318daf964514ffbf41583 25/docs/cmdline-opts/append.md) and there’s an “Example” field in that file.

formatting data in a table

Quite a few people said that man ascii was their favourite man page, which looks like this:

Oct Dec Hex Char

───────────────────────────────────────────

000 0 00 NUL '\0' (null character)

001 1 01 SOH (start of heading)

002 2 02 STX (start of text)

003 3 03 ETX (end of text)

004 4 04 EOT (end of transmission)

005 5 05 ENQ (enquiry)

006 6 06 ACK (acknowledge)

007 7 07 BEL '\a' (bell)

010 8 08 BS '\b' (backspace)

011 9 09 HT '\t' (horizontal tab)

012 10 0A LF '\n' (new line)

Obviously man ascii is an unusual man page but I think what’s cool about this man page (other than the fact that it’s always

useful to have an ASCII reference) is it’s very easy to scan to find the

information you need because of the table format. It makes me wonder if there

are more opportunities to display information in a “table” in a man page to make

it easier to scan.

the GNU approach

When I talk about man pages it often comes up that the GNU coreutils man pages (for example man tail) don’t have examples, unlike the OpenBSD man pages, which do have examples.

I’m not going to get into this too much because it seems like a fairly political topic and I definitely can’t do it justice here, but here are some things I believe to be true:

- The GNU project prefers to maintain documentation in “info” manuals instead of man pages. This page says “the man pages are no longer being maintained”.

- There are 3 ways to read “info” manuals: their HTML version, in Emacs, or with a standalone

infotool. I’ve heard from some Emacs users that they like the Emacs info browser. I don’t think I’ve ever talked to anyone who uses the standaloneinfotool. - The info manual entry for tail is linked at the bottom of the man page, and it does have examples

- The FSF used to sell print books of the GNU software manuals (and maybe they still do sometimes?)

After a certain level of complexity a man page gets really hard to navigate: while I’ve never used the coreutils info manual and probably won’t, I would almost certainly prefer to use the GNU Bash reference manual or the The GNU C Library Reference Manual via their HTML documentation rather than through a man page.

a few more man-page-adjacent things

Here are some tools I think are interesting:

- The fish shell comes with a Python script to automatically generate tab completions from man pages

- tldr.sh is a community maintained database of examples, for example you can run it as

tldr grep. Lots of people have told me they find it useful. - the Dash Mac docs browser has a nice man page viewer in it. I still use the terminal man page viewer but I like that it includes a table of contents, it looks like this:

it’s interesting to think about a constrained format

Man pages are such a constrained format and it’s fun to think about what you can do with such limited formatting options.

Even though I’m very into writing I’ve always had a bad habit of never reading documentation and so it’s a little bit hard for me to think about what I actually find useful in man pages, I’m not sure whether I think most of the things in this post would improve my experience or not. (Except for examples, I LOVE examples)

So I’d be interested to hear about other man pages that you think are well designed and what you like about them, the comments section is here.

WebMCP – a much needed way to make agents play with rather than against the web

A bookmarks post that closes all the tabs

I am deeply frustrated with my inability to stick to the plan and do this post once a month. But I will really make an effort from now on because the more I delay the more links (and tabs) pile on and I end up not being able to share everything.

Bookmarks related to tech and web development

- Webmentions by Joe Crawford.

- Selfish reasons for building accessible UIs by Nolan Lawson.

- Radical Web.

- Bot or not? by Oleh.

- Charity Digital Skills.

- Being lazy with view-transition-old and -new by Cyd Stumpel.

- Url Town.

- Better CSS layouts: Time.com Hero Section by Ahmad Shadeed.

- Sceptical about website carbon emission figures by Fershad Irani.

- zine - personal websites and the law by Ava.

- Responsive Nav by Ariel Salminen.

- This website has no class by Adam Stoddard.

- Taking a shot at the double focus ring problem using modern CSS by Eric Bailey.

- Build for the Web, Build on the Web, Build with the Web by Harry Roberts.

- You no longer need JavaScript by Lyra.

- How To Argue With An AI Booster by Edward Zitron.

- Creating proportional, equal-height image rows with CSS, 11ty, and Nunjucks by Jeremy Robert Jones.

- Making sense of accessibility and the law by Martin Underhill.

- An Interactive Guide to SVG Paths by Josh Comeau.

- Still being a woman in tech by Melanie Crissey.

- Github Action that automatically compresses JPEGs, PNGs, WebPs & AVIFs in Pull Requests. by calibreapp.

- Generative AI: What You Need To Know by Baldur Bjarnason.

- Writing Code Was Never The Bottleneck by Pedro Tavares.

- Hack to the Future - Frontend by Matt Hobbs.

- Secret Web by Benjamin Hollon.

- JavaScript dos and donts by Mu-An Chiou.

- A pragmatic guide to modern CSS colours - part one by Kevin Powell.

- Opt Out Project by Janet Vertesi.

- My first months in cyberspace by Phil Gyford.

- Could Open Graph Just Be a CSS Media Type? by Scott Jehl.

- Top layer troubles: popover vs. dialog by Stephanie Eckles.

- Web Platform Status.

- Don't start testing accessibility with a screen reader by Erik Kroes.

- Not so short note on aria-label usage – Big Table Edition by stevef.

- HMRC's Virtual Empathy Hub.

- Dark Patterns Detective.

- Come to the light-dark() Side by Sara Joy.

- CSS light-dark() by Mayank.

- More options for styling details by Bramus.

- Preserving the Pixel Art Look in Web Content by kirupa.

- What is it like to use a screen reader on an inaccessible website? by Craig Abbott.

- Browser logos.

- Please stop externalizing your costs directly into my face by Drew DeVault.

- The case for “old school” CSS by Chen Hui Jing.

- The rise of Whatever by Eevee.

- What I Wish Someone Told Me When I Was Getting Into ARIA by Eric Bailey.

- the web as a space to be explored by Roy Tang.

- How to (not) use aria-label, -labelledby and -describedby by Steve Frenzel.

- Cally by Nick Williams.

- Five ways cookie consent managers hurt web performance (and how to fix them) by Cliff Crocker.

- Get out of my head.

- no web without women by Selman.

- Bringing Joy Back to the Web: Fediverse vs. Centralized Apps by Richard MacManus.

- Wikipedia:Signs of AI writing.

- How to Surf the Web in 2025, and Why You Should by David Cain.

- The 'Accessibility' link is a Lie: My Adventures in Weaponizing Corporate Virtue Signaling by Robert Kingett.

- US dad takes photos of his naked toddler for the doctor, Google flags him as criminal

- Webring List.

- Pattern Craft.

- Simplified Accessibility Testing.

- A guide to creating accessible PDFs using free tools by Steve Frenzel.

- Zero to internet: your first website

- The Web you want

- Fixing Baselines by Roma Komarov.

- Why RSS matters by Ben Werdmuller.

Other bookmarks

- Productivity traps I fall into regularly by Dave Rupert.

- All the jobs I failed to get by Terence Eden.

- Clara's blogroll by Clara.

- Shamelessness as a strategy by Nadia Asparouhova.

- Everything I Know about Self-Publishing by Kevin Kelly.

- reasons to blog by chia amisola.

- Publishing personal content online while hiding yourself is a flawed but rational response to a broken internet by TDP.

- little directory of calm

- Friday Night Meatballs: How to Change Your Life With Pasta by Sarah Grey.

- 47 lessons by Ben Werdmuller.

- HTML Zine.

- Just a QR Code.

- Monastery of Sankt Blamensir via Maya.

- Literature Is Not a Vibe: On ChatGPT and the Humanities by Rachele Dini.

- England football team Nazi salute.

- vegan and vegetarian restaurants, ice cream parlors, cafés etc. registered in OpenStreetMap.

- Dicing an onion the Mathematically Optimal Way by Andrew Aquino with Russell Samora and Jan Diehm.

- The "washerwoman" folklore motif in Europe and North America.

- On keeping up with friends and contacts by joelchrono.

Refactoring English: Month 14

New here?

Hi, I’m Michael. I’m a software developer and founder of small, indie tech businesses. I’m currently working on a book called Refactoring English: Effective Writing for Software Developers.

Every month, I publish a retrospective like this one to share how things are going with my book and my professional life overall.

Highlights

- A new strategy for finding book readers is having positive results.

- I had a breakthrough experience by letting an AI agent run in unrestricted mode.

- I’ve been using AI to correct decisions I regret about my tech stack.

Goal grades

At the start of each month, I declare what I’d like to accomplish. Here’s how I did against those goals:

Eversource EV Rebate Program Exposed Massachusetts Customer Data

I recently claimed a rebate for installing an electric vehicle (EV) charger, only to discover that Eversource, my power supplier, was publicly exposing personal information of customers who applied, including:

- Full names

- Vehicle registration certificates (including plate number and vehicle identification number)

- Home addresses

- Email addresses

- Phone numbers

I’ll include the backstory that led me to the vulnerability, but if you just want to know about the security vulnerability, you can skip to that.