Reading List

Teaching by filling in knowledge gaps from Julia Evans RSS feed.

Teaching by filling in knowledge gaps

Hello! This post (like patterns in confusing explanations) is another one in the “julia attempts to articulate her teaching strategy” series.

I’ll start out by talking about a “backwards” approach to learning that I think a lot of you will recognize (do projects first without fully understanding what you’re doing, fill in missing knowledge after), and then talk about I try to teach in a way that works better with that mode of learning.

how I’ve learned programming: backwards

There are a lot of “basic” concepts in programming, like memory management, networking, operating systems, assembly, etc. You could imagine that you learn programming by first starting with the basic concepts and then learning abstractions on top of those concepts.

But, even though I have a very traditional CS background, that’s not how it’s usually worked for me. Instead, here’s a real example from how I learned about websites:

- Set up a website (for example using Apache)

- Three years later, realize “wait, I have no idea how that worked at all”

- Learn the basics of HTTP

Of course, to really understand how websites work, you do need to understand the basics of HTTP. But at the same time, you can make lots of great websites without knowing anything about HTTP except that 404 means “not found”.

it’s fun to build a lot of cool stuff quickly

Obviously I don’t actually think it’s bad to make websites without knowing HTTP. It’s fun! You can make a website and set up nginx or Apache by copying some stuff you found on Stack Overflow and didn’t fully understand, and then you have a website on the internet! I find it very fun to start out with a technology by quickly building a bunch of stuff with it without understanding exactly how it works (like making this shader).

it’s fun to fill in the information you’ve missed

Now that you have your website, here’s a way you could imagine learning about HTTP headers:

- Your website suddenly gets really popular, so you put it behind a CDN to save money

- But some of your pages are dynamic and you don’t want to cache them

- So then you need to learn about browser caching and the

Cache-ControlHTTP header - And maybe then you learn about headers in general and find some other headers you want to set

I think that learning about HTTP headers after you already have a website is way more fun and a lot easier than learning about them before you have a website.

It’s much more obvious why you might want to use them, and you’re a lot more likely to remember the information later.

learning abstractions first results in knowledge gaps

Let’s say you start learning to make websites by learning Ruby on Rails. Rails abstracts away a lot of things, like SQL (through its ORM), sockets, and HTTP.

So if you learn Rails, you’re not likely to “naturally” pick up HTTP or sockets or SQL the same way you would if you were writing a webserver from scratch.

jobs today have more abstractions than they used to

I asked on twitter what people feel was easier to learn 15 years ago. One example a lot of people mentioned was the command line.

I was initially a bit surprised by this, but when I thought about it makes sense – if you were a web developer 15 years ago, it’s more likely that you’d be asked to set up a Linux server. That means installing packages, editing config files, and all kinds of things that would get you fluent at the command line. But today a lot of that is abstracted away and not as big a part of people’s jobs. For example if your site is running on Heroku, you barely have to know that there’s a server there at all.

I think this applies to a lot more things than the command line – networking is more abstracted away than it used to be too! In a lot of web frameworks, you just set up some routes and functions to handle those routes, and you’re done!

Abstractions are great, but they’re also leaky, and to do great work you sometimes need to learn about what lives underneath the abstraction.

how can we help people understand what’s underneath the abstractions?

Here some of you might be tempted to go on a rant about how “kids these days” don’t understand databases or networking or the command line or whatever thing has most annoyed you.

But that’s boring, we’ve had that argument a billion times, and it’s ineffective – people are going to keep learning abstractions first! It’s fun to learn abstractions first! You can get a lot of work done without understanding sockets!

But obviously I do think it’s important to fill in some of those knowledge gaps when it’s relevant to your job – that’s what this whole blog is about!

So let’s talk about how we can help people fill in some of their knowledge gaps (when they want/need to!), but by actually providing useful information instead of ranting about what “kids these days” should know :)

my steps for explaining something

I don’t actually have explicit steps I use when teaching, but I spent some time thinking about my approach and here’s what I think I do.

Instead of starting “at the beginning” when explaining a topic, what I usually do when writing a blog post or comic is:

- notice a useful idea that I think is on the edge of a lot of people’s knowledge

- make a bunch of assumptions about what I think that group of people generally know (usually based on what I know and what I think my friends/coworkers know)

- explain the idea using those assumptions

Here are a few more guidelines that I use when teaching “backwards”.

- use people’s existing knowledge when teaching

- explain just one concept at a time

- use bugs to peel back abstractions

Let’s talk more about each of those!

use people’s existing knowledge when teaching

One mistake I see people make a lot when they notice someone has a knowledge gap is:

- notice that someone is missing a fundamental concept X (like knowing how binary works or something)

- assume “wow, you don’t know how binary works, you must not know ANYTHING”

- give an explanation that assumes the person basically doesn’t know how to program at all

- waste a bunch of their time explaining things they already know

But this is a huge missed opportunity when explaining a concept to a professional programmer – they already know a lot! Any professional programmer definitely knows a lot of things that are very related to how binary works.

explain just one concept at a time

Because I don’t have a lot of information about who I’m writing for, I try to:

- only address one major gap at a time

- make it super clear what the gap I’m addressing is

Then people can easily tell if what I’m writing is relevant to them, get the information they’re interested in, and leave.

It might seem like this wouldn’t work because everyone has a totally unique set of knowledge, but actually there are a lot of interesting facts that happen to be on the edge of a LOT of people’s knowledge. So it’s all about identifying patterns (“hmm, I didn’t realize X for a long time, I bet other people didn’t either”).

bugs are an amazing way to learn what’s under an abstraction

My favourite way to learn what’s underneath an abstraction is bugs! Bugs often break through abstraction boundaries, like this performance issue that was caused by a TCP setting.

So they’re a great excuse to learn what’s underneath, they show you exactly how the underlying thing (like TCP) is connected to the abstraction (like an HTTP request). And they inherently help you learn one step at a time, because each bug will usually teach you about just one or two things.

teaching by filling in knowledge gaps can be faster

One thing I love about teaching this way is that if the reader is already using a tool, I can assume that they know a bunch of basic things about it and skip straight to the interesting parts.

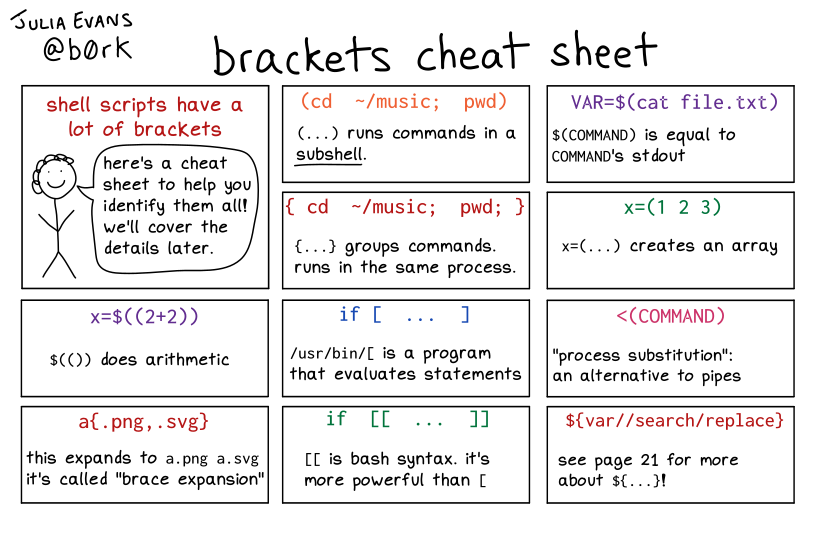

For example, let’s look at this bash cheat sheet.

This cheat sheet assumes that you know:

- what bash is

- that variables are referenced in bash with

$VAR - what “stdout” means

- what it means to search and replace in a string

- what an array is

And I’d guess that most people who are writing bash scripts know those things! But I’d also guess that many people who write bash scripts don’t know that:

/usr/bin/[is a program (actually in bash[is a builtin, but it’s a builtin that behaves the same way as the program/usr/bin/[)- the curly brace in

a{.png.svg}has a totally different meaning from the one in{ command1; command2 } - you can search and replace in a string with

${}

example of teaching by filling in knowledge gaps: bite size bash

Last year I wrote a zine called bite size bash about how bash scripting works. (the above cheat sheet is part of it)

You might think that I’d explain some basic things like “what bash is” and the usual syntax of a bash script. But I didn’t. That’s because I wrote the zine for people who were already using bash.

Instead, I went through the most things bash script writers don’t understand about bash (variable assignment, how if statements work, how to quote things, etc) and explained how those things actually work in bash.

filling in knowledge gaps at the drop-in tutoring center

To me teaching and writing in this way feels very natural. But people have told me they find it really difficult to write without explaining everything from the beginning.

I think my teaching style might be informed in some way by my experience working as a tutor as a drop-in math tutoring centre. I’ve had 5 or so part time jobs (from age 15-20) doing math or physics tutoring where I basically had to talk to random students who were confused about something for 20 minutes. I could probably only teach them only 1 or 2 things in those 20 minutes, and I might only ever meet the person once. So I had to quickly figure out what they already knew and what kind of information might help them.

I learned to listen a lot and not jump to conclusions about what the person didn’t know – often they already actually understood a lot about the math class they were taking and I just needed to explain one or two small things.

I think of writing on the internet as being kind of similar. I have no idea who’s reading my writing or what they already know, and they’re probably going to only spend 10 minutes or so reading it. So I can only intervene in a really limited way.

I think unpeeling abstractions is what I’m trying to do in my writing

I think “show people what lives underneath their abstractions” is a big part of what I’m trying to do with my writing. This might be why I’m so obsessed with bugs – they’re such a natural way to learn about what’s hiding under your abstractions in a way that’s actually relevant to your work.

Thanks to Miles, Jake, Dan, Matthew, and Kamal for reading a draft of this post.