Reading List

Comforting Myths from Infrequently Noted RSS feed.

Comforting Myths

In several recent posts, I've attempted to address how the structure of standards bodies, and their adjacent incubation venues, accelerates or suppresses the potential of the web as a platform. The pace of progress matters because platforms are competitions, and actors that prevent expansions of basic capabilities risk consigning the web to the dustbin.

Inside that framework, there is much to argue over regarding the relative merits of specific features and evolutionary directions. This is healthy and natural. We should openly discuss features and their risks, try to prevent bad consequences, and work to mend what breaks. This competitive process has made browsers incredibly safe and powerful for 30 years.

Until iOS, that is.

Imagine my surprise upon hearing that Apple isn't attempting to freeze the web in amber, preserving advantages for its proprietary platform, and that it instead offers to redesign proposals it disagrees with.

As I have occasionally documented, this has not been my experience. I have relatively broad exposure to the patterns of Apple's collaboration, having designed, advised on, or led teams that built dozens of features across disparate areas of the platform since the Blink fork.1

But perhaps this was the wrong slice from which to judge? I've been hearing of Apple's openness to collaboration on challenging APIs so often that either my priors are invalid, or something else is at work. To find out, I needed data.

Background

A specific parry gets deployed whenever WebKit's sluggish feature pace comes up: “controversial” features “lack consensus” or “are not standards” or “have privacy and security problems” (unspecified). The corollary being that Apple engages in good-faith to address these developer needs in other ways, even in areas where they have overtly objected.

Apple's engine has indisputably trailed Blink and Gecko in all manner of features over the past decade. This would not be a major problem, except that Apple prevents other browsers from delivering better and more competitive web engines on iOS.

Normally, consequences for not adopting certain features arrive in the market. Browsers that fail to meet important needs, or drop the ball on quality lose share. This does not hold on iOS because no browser can ship a less-buggy or more capable engine than Apple's WebKit.

Because competitors are reduced to rebadging WebKit, Apple has created new responsibilities and expectations for itself.2 Everyone knows iOS is the only way to reach wealthy users, and no browser can afford to be shut out of that slice of the mobile market. Therefore, the quality and features of Apple's implementation matter greatly to the health and competitiveness of the web.

This put's Apple's actions squarely in the spotlight.

Is Apple Engaged In Constructive API Redesign?

It's possible to size up Apple's appetite for problem-solving in several ways. We can look to understand how frequently Apple ships features ahead of, or concurrently with, other engines because near-simultaneous delivery is an indicator of co-design. We can also look for visible indications of willingness to engage on thorny designs, searching for counter-proposals and shipped alternatives along the way.

General Trends

This chart tracks single-engine omissions over the past decade; a count of designs which two engines have implement but which a single holdout prevents from web-wide availability:

Safari consistently trails every other engine, and APIs missing from it impact every iOS browser.

Thanks to the same Web Features data set, many views are possible. This data shows that there are currently 178 features in Chromium that are not available in Safari, and 34 features in Safari that are not yet in Chromium. (or 179 and 37 for mobile, respectively). But as I've noted previously, point-in-time evaluations may not tell us very much.

I was curious about delays in addition to omissions. How often do we see evidence of simultaneous shipping, indicating strong collaboration? Is that more or less likely than leading vendors feeling the need to go it alone, either because of a lack of collaborative outreach, or because other vendors do not engage when asked?

To get a sense, I downloaded all the available data (JSON file), removed features with no implementations, removed features introduced before 2015, filtered to Chrome, Safari, and Firefox, then aggregated by year. The resulting data set is here (JSON file).

The data can't determine causality, but can provide directional hints:

Leading Launches by Year

Features Shipped Within One Year of the Leader

Features Shipped Two+ Years After the Leader

Safari rarely leads, but that does not mean other vendor's designs will stand the test of time. But if Apple engages in solving the same problems, we would expect to see Safari leading on alternatives3 or driving up the rates of simultaneously shipping features once consensus emerges. But these aren't markedly increased. Apple can, of course, afford to fund work into substitutes for “problematic” APIs, but it doesn't seem to.

Narratives about collaboration in tricky areas take more hits from Safari's higher incidence of catch-up launches. These indicate Apple shipping the same design that other vendors led with, but on a delay of two years or more from their first introduction. This is not redesign. If there were true objections to these APIs, we wouldn't expect to see them arrive at all, yet Apple has done more catching up over the past several years than it has shipped APIs with other vendors.

This fails to rebut intuitions developed from recent drops of Safari features (1, 2) composed primarily of APIs that Apple's engineers were not primary designers of.

But perhaps this data is misleading, or maybe I analysed it incorrectly. I have heard allusions to engagement regarding APIs that Apple has publicly rejected. Perhaps those are where Cupertino's standards engineers have invested their time?

Hard Cases

Most of the hard cases concern APIs that Apple (and others) have rightly described as having potentially concerning privacy and security implications. Chromium engineers agreed those concerns have merit and worked to address them; we called it “Project Fugu” for a reason. In addition to meticulous design to mitigate risks, part of the care taken included continually requesting engagement from other vendors.

Consider the tricky cases of Web MIDI, Web USB, and Web Bluetooth.

Web MIDI

Apple has supported MIDI in macOS for at least 20 years — likely much longer — and added support for MIDI on iOS with 2010's introduction of Core MIDI in iOS 4.2. By the time the first Web MIDI proposals broke cover in 2012, MIDI hardware and software were the backbone of digital music and a billion dollar business; Apple's own physical stores were stocking racks of MIDI devices for sale. Today, an overwhelming fraction of MIDI devices explicitly list their compatibility with iOS and macOS.

It was therefore a clear statement of Apple's intent to cap web capabilities when it objected to Web MIDI's development just before the Blink fork. The objections by Apple were by turns harsh, condescendingly ignorant and imbued with self-fulfilling stop-energy; patterns that would repeat post-fork.

After the fork and several years of open development (which Apple declined to participate in), Web MIDI shipped in Chromium in early 2015. Despite a decade to engage, Safari has not shipped Web MIDI, Apple has not provided a “standards position” for it4, and has not proposed an alternative. To the best of my knowledge, Apple have also not engaged in conversations about alternatives, despite being a member of the W3C's Audio Working Group which has published many Working Drafts of the API. That group has consistently included publication of Web MIDI as a goal since 2012.

Across 11 charters or re-charters since then, I can find no public objection within the group's mailing list from anyone with an @apple.com email address.5 Indeed, I can find no mentions of MIDI from anyone at Apple on the public list. Obviously, that is not the same thing as agreeing to publication as a Recommendation, but it also not indicative of any attempts at providing an alternative.

But perhaps alternatives emerged elsewhere, e.g., in an Incubation venue?

There's no counter-proposal listed in the WebKit explainers repository, but maybe it was developed elsewhere?

We can look for features available behind flags in Safari Technology Preview and read the Tech Preview release notes. To check them, I used curl to fetch each of the 127 JSON files that are, apparently, the format for Safari's release notes, pretty-printed them with jq, then grepped case-insensitively for mention of “audio” and “midi”. Every mention of “audio” was in relation to the Web Audio API, the Web Speech API, WebRTC, the <audio> element, or general media playback issues. There were zero (0) mentions of MIDI.

I also cannot locate any public feedback on Web MIDI from anyone I know to have an @apple.com email address in the issue tracker for the Web Audio Working Gropup or in WICG except for a single issue requesting that WICG designs look “less official.”

The now-closed Web MIDI Community Group, likewise, had zero (0) involvement by Apple employees on its mailing list or on the successor Audio Community Group mailing list. There were also no (0) proposals covering similar ground that I was able to discern on the Audio CG issue list.

Instead, Apple have issued a missive decrying Web MIDI as a privacy risk. As far as anyone can tell, this was done without substantive analysis or engagement with the evidence from nearly a decade of deploying it in Chromium-based browsers.

If Apple ever offered an alternative, or to collaborate on a redesign, or even an evidence-based case for opposing it,6 I cannot find them in the public record.7

Web USB

USB is a security sensitive API, and Web USB was designed with those concerns in mind. All browsers that ship Web USB today present “choosers” that force users to affirmatively select each device they provide access to, from which sites, and always show ambient usage indicators that let users revoke access. Further, sensitive device classes that are better covered by more specific APIs (e.g., the Filesystem Access API instead of USB Mass Storage) are restricted.

This is far from the Hacker News caricature of "letting any web page talk to your USB devices," allowing only point connections between individual devices and sites, with explicit controls always visible.

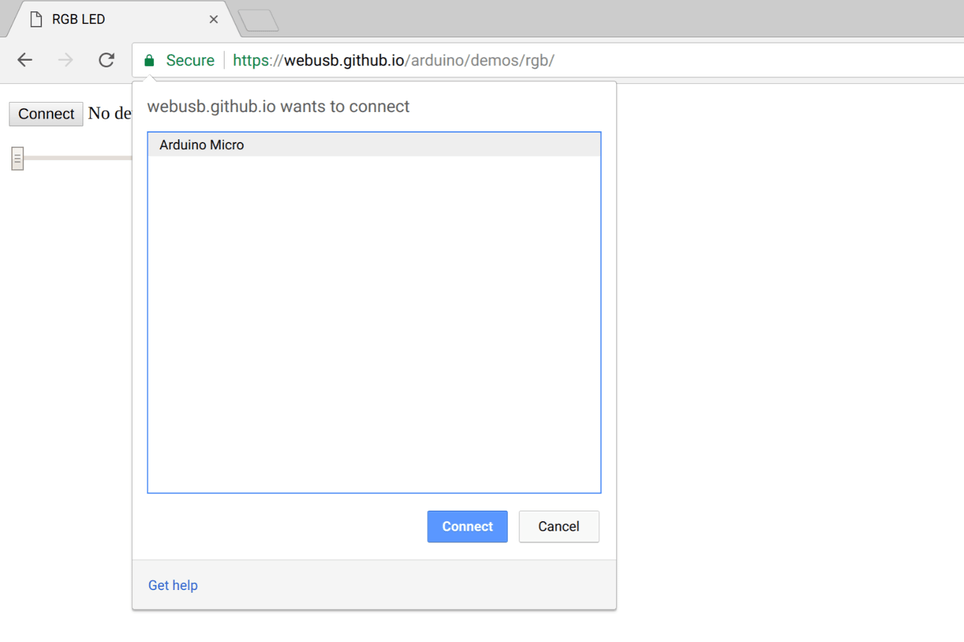

After two years of public development and a series of public Origin Trials lasting seven months (1, 2), the first version of the API shipped in Chrome 61, released September 2017.

I am unable to locate any substantive engagement from Apple about alternatives for the motivating use-cases outlined in the spec.

With many years of shipping experience, we can show that these needs have been successfully addressed by WebUSB; e.g. teaching programming in classrooms. More than a decade after it was first approached about them, it's unclear what Apple's alternative is. Hollowing out school budgets to buy Cupertino's high-end devices to run unsafe, privacy-invading native apps?

Apple have included Web USB on the list of APIs they “decline to implement” and quite belatedly issued a “standards position” opposing the design. But no counter-proposal was developed or linked from those threads, despite being asked directly if there might be more palatable alternatives.

I can locate no appetite from Apple's standards engineers to address these use-cases, know of no enquiries into data about our experiences shipping them, and can find no constructive counterproposals. Which raises the obvious question: if Apple does engage to develop counterproposals in tricky areas, how long are counterparties meant to wait? More than eight years?

Web Bluetooth

Like Web USB, Web Bluetooth was designed from the ground-up with safety in mind and, as a result, has been incredibly safe and deployed at massive scale for eight years. It relies on the same chooser model in Chromium-based browsers.

As with all Project Fugu device APIs, Web Bluetooth was designed to reduce ambient risks — no access to Bluetooth Classic, available only on secure sites, and only in <iframe>s with explicit delegation, etc. — and to give implementers flexibility about the UIs they present to maximise trust and minimise risk. This included intentionally designing flexibility for restricting access based on context; e.g., only from installed PWAs, if a vendor chooses that.

The parallels with Web USB continue on the standards track. I can locate no engagement from any @apple.com or @webkit.org email addresses on the public-web-bluetooth mailing list. In contrast, when design work began in 2014 and every browser vendor was invited to participate, Mozilla engaged. I can find no evidence of similar openness on the part of Apple, nor practical counter-proposals.

Over more than three years of design and gestation in public, including very public Origin Trials, Apple did not provide constructive feedback, develop counter-proposals, or offer to engage in any other way I can find.

This appears to be a pattern.

From a deep read of the “standards position” threads for designs Apple opposes, I cannot find evidence that Cupertino has ever offered a counter-proposal to any API it disfavours.

These threads do demonstrate a history of downplaying clearly phrased developer needs, rather than proactive engagement, and it seems the pattern is that parties must beg Apple to belatedly form an opinion. When there is push-back, often after years of radio silence, requesters (not Apple) also have to invent potential alternatives, which Apple may leave hanging without engagement for years.

Worse, there are performative expressions of disinterest which Apple's standards engineers know are in bad-faith. An implementer withholding engagement from a group, then claiming a lack of implementer engagement in that same venue as a reason not to support a design, is the sort of self-serving, disingenuous circularity worthy of disdain.

Overall Impressions

Perhaps both the general trends and these specific high-profile examples are aberrant. Perhaps Apple's modus operandi isn't to:

- Ignore new incubations, even when explicitly asked to participate.

- Fail to register concerns early and collaboratively, where open design processes could address them.

- Force web developers and other implementers to request “positions” at the end of the design process because Apple's disengagement makes it challenging to understand Cupertino's level of support (or antipathy).

Mayhaps it's not simply the predicable result of paltry re-investments in the web by a firm that takes eye watering sums from it.

If so, I would welcome evidence to that effect. But the burden of proof no longer rests with me.8

What's Happening Here?

It's hard to say why some folks are under the impression that Apple are generous co-designers, or believe Apple's evocative statements about hard-case features are grounded in analysis or evidence. We can only guess at motive.

The most generous case I can construct is that Apple's own privacy and security failures in native apps have scared it away, and that spreading FUD is cover for those sins. The more likely reality is that upper management fears PWAs and wants to keep them from threatening the App Store with safe alternatives that don't require paying Apple's vig.

Whatever the cause, the data does not support the idea that Apple visibly engages in constructive critique or counter-proposal in these areas.

Moreover, it shows that many of Apple's objections and delays were unprincipled. It should be every browser's right to control the features it enables, and Cupertino is entirely within those rights to avoid shipping features in Safari. But the huge number of recent “catch-up” features tells a story that aligns more with covering for embarrassing oversights, rather than holding a line on quality, privacy, or security.

On the upside, this suggests that if and when web developers press hard for capabilities that have been safe on other platforms, Cupertino will relent or be regulated into doing so. It scarcely has a choice while simultaneously skimming billions from the web and making arguments like these to regulators (PDF, p35):

The moment iPhone users around the world can install high-quality browsers, the conversational temperature about missing features and reliability will drop considerably. Until then, it remains important that Apple bear responsibility for the problems Apple is causing not only for Apple, but for us all.

FOOTNOTES

My various roles since the Blink fork have included:

- TC39 representative

- Co-designer of Service Workers ('12-'15)

- Co-Tech Lead for Project Fizz ('14-'16)

- Three-time elected member of the W3C's Technical Architecture Group ('13-'19)

- Web Standards Tech Lead for Chrome ('15-'21)

- Co-Tech Lead for Project Fugu ('17-'21)

- Co-designer of Isolated Web Apps ('19-'21)

- Blink API OWNER ('18-present)

- Ongoing advisor to Edge's web standards team

In my role as TAG member, Fizz/Fugu TL, and API OWNER I've designed, reviewed, or provided input on dozens of web APIs. All of this work has been collaborative, but these positions have given me a nearly unique perch from to observe the ebb and flow of new designs from, particularly on the "spicy" end of the spectrum. ⇐

Apple has many options for returning voluntarity to the market for iOS browsers.

Most obviously, Apple can simply allow secure browsers to use their own engines. There is no debate that this is possible, that competitors generally do a better job regarding security than Apple, and that competitors would avail themselves of these freedoms if allowed.

But Apple has not allowed them.

Open Web Advocacy has exhaustively documented the land mines that Apple has strewn in front of competitors that have the temerity to attempt to bring their own engines to EU users. Apple's choice to geofence engine choice to the EU, indefensible implementation roadblocks, poison-pill distribution terms, and the continued prevarications and falsehoods offered in their defence, are choices that Apple is affirmatively and continually making.

Less effectively, Apple could provide runtime flags for other browsers to enable features in the engine which Apple itself does not use in Safari. Paired with a commitment to implement features in this way on a short timeline after they are launched in other engines on other OSes, competing vendors could risk their own brands without Apple relenting on its single-implementer demands. This option has been available to Apple since the introduction of competing browsers in the App Store. As I have argued elsewhere, near-simultaneous introduction of features is the minimum developers should expect of a firm that skims something like $19BN/yr in profits from the web (a ~95% profit rate, versus current outlays on Safari and WebKit).

Lastly, Apple could simply forbid browsers and web content on iOS. This policy would neatly resolve the entire problem. Removing Safari, along with every other iOS browser, is intellectually and competitively defensible as it removes the “special boy” nature of Safari and WebKit. This would also rid Apple of the ethical stain of continuing to string developers and competitors along within standards venues when it is demonstrably an enemy of those processes. ⇐

Apple regularly goes it alone when it is convinced about a design. We have seen this in areas as diverse as touch events, notch CSS, web payments, "liquid glass" effects, and much else. It is not credible to assume that Apple will only ship APIs that have an official seal of an SDO given Cupertino's rich track record of launch-and-pray web APIs over the years. ⇐

In fairness to Apple regarding a "standards position" for Web MIDI, the feature predates Apple's process. But this brings up the origin of the system.

Why does this repository exist? Shouldn't it be rather obvious what other implementers think of that feature, assuming they are engaged in co-design?

Yes, but that assumes engagement.

Just after the Blink fork, a series of incidents took place in which Chromium engineers extrapolated from vaguely positive-sounding feedback in standards meetings when asked about other vendor's positions as part of the Blink Launch Process. This feedback was not a commitment from Apple (or anyone else) to implement, and various WebKit leaders objected to the charachterisations. As a way to avoid over-reading tea leaves in the absence of more fullsome co-design, the "standards position" process was erected in WebKit (and Gecko) so that Chromium developers could solicit "official" positions in the many instances where they were leading on design, in lieu of clearer (tho long invited) engagement.

If this does not sound like it augurs well for assertions that Apple engages to help shape designs in a timely way...well, you might very well think that. I couldn't possibly comment. ⇐

There may have been Formal Objections (as defined by the W3C process) in private communications, but Member Confidentiality at the W3C precludes me from saying either way. If Apple did object in this way, it will have to provide evidence of that objection for the public record, as I cannot. ⇐

Apple's various objections to powerful features have never tried to square the obvious circle: why are camera and microphone access (via

getUserMedia()) OK, but MIDI et. al are not? What evidence supports the notion that adding chooser-based UIs will lead to pervasive privacy issues that cannot be addressed through mechanisms like those Apple is happy to adopt for Geolocation? Why, despite their horrendous track records, are native apps the better alternative? ⇐Mozilla objected to Web MIDI on various grounds over the years, and after getting utterly roasted by its own users over failing to support the API, shipped support in Firefox 108 (Dec '22).

The larger question of Mozilla's relationship to device APIs was a winding road. It eventually culminated (for me) in a long discussion at a TAG meeting in Stockholm with EKR of TLS and Mozilla fame.

By 2016, Mozilla was licking its wounds from the failure of Firefox OS and retrenching around a less expansive vision of the future of the web. Long gone were the aspirations for "WebAPIs". Just a few short years earlier, Mozilla would have engaged (if not agreed) about work in this space, but an overwhelming tenor of conservativism and desktop-centricity radiated from Mozilla by the time of this overlapping IETF/W3C meeting.

It didn't make the notes, but my personal recollection of how we left things late in the afternoon in Stockholm was EKR claiming that bandwidth for security reviews was the biggest blocker that and that it was fine if we (Chromium) went ahead with these sorts of designs to prove they wouldn't blow up the world. Only then would Mozilla perhaps consider versions of them.

True to his word, Mozilla eventually shipped Web MIDI on EKR's watch. If past is prologue, we'll only need to wait another three to five years before Web Bluetooth et al. join them. ⇐

My memory is famously faulty, and I have been engaged in a long-running battle with Apple's legal folks relating to the suppression of browser choice on iOS. All of that colours my vision, and so here I have tried to disabuse myself of less generous notions by consulting public evidence to support Apple's case.

From what I was able to gather over many hours was overwhelmingly inculpatory. It is not possible from reading these threads and data points — rather relying on my own recollections — to sustain a belief that Apple have either provided timely constructive feedback on tricky APIs, or worked to solve the problems they address. But I am, in the end, heavily biased.

If my conclusions or evidence are wrong, I would very much appreciate corrections; my inbox and DMs are open.

If reliable evidence is provided, I will update this blog post to include it, and I encourage others to post on this topic in opposition to my conclusions. It should not be hard for Apple to make the case, assuming there is evidence to support it, that I've missed important facts. It would have both regulatory and persuasive valence regarding questions I have raised relating to Apple's footprint in the internet standards community. ⇐