Reading List

New talk: Learning DNS in 10 years from Julia Evans RSS feed.

New talk: Learning DNS in 10 years

Here’s a keynote I gave at RubyConf Mini last year: Learning DNS in 10 years. It’s about strategies I use to learn hard things. I just noticed that they’d released the video the other day, so I’m just posting it now even though I gave the talk 6 months ago.

Here’s the video, as well as the slides and a transcript of (roughly) what I said in the talk.

the video

the transcript

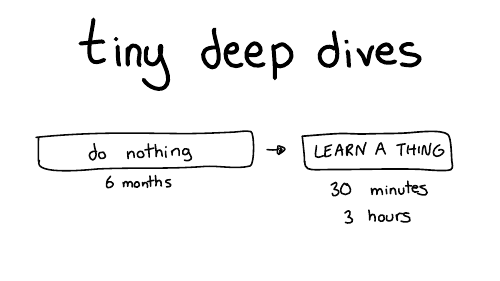

So, we're going to talk about learning through a series of tiny deep dives. My favorite way of learning things is to do nothing, most of the time.

That's why it takes 10 years.

So for six months I'll do nothing and then like I'll furiously learn something for maybe 30 minutes or three hours or an afternoon. And then I'll declare success and go back to doing nothing for months. I find this works really well for me.

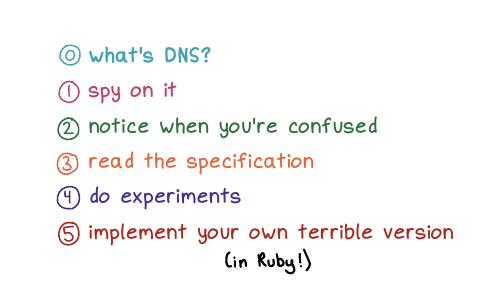

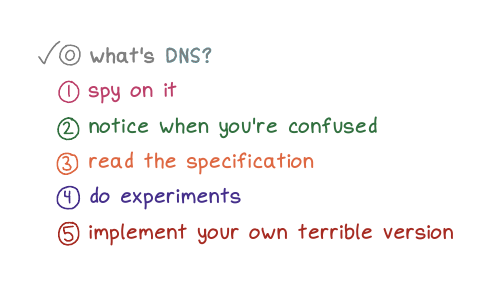

Here are some of the strategies we're going to talk about for doing these tiny deep dives

First, we're going to start briefly by talking about what DNS is.

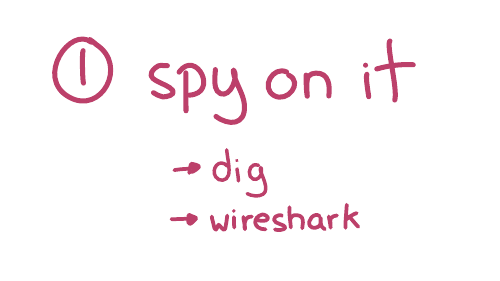

Next, we're going to talk about spying on DNS.

Then we're gonna talk about being confused, which is my main mode. (I'm always confused about something!)

Then we'll talk about reading the specification, we'll going to do some experiments, and we're going to implement our own terrible version of DNS.

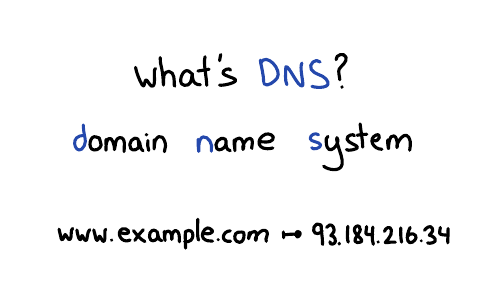

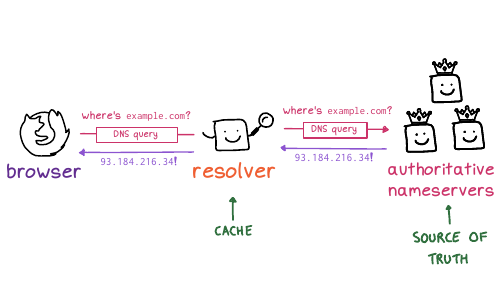

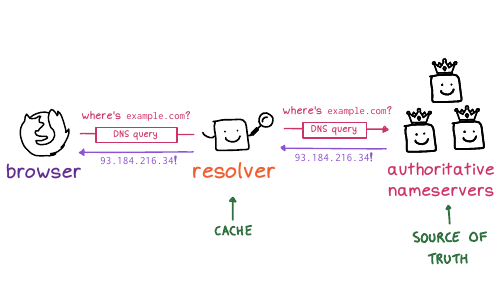

www.example.com, your browser

needs to look up that website's IP address. So DNS translates

domain names into IP addresses. It looks up other information about domain

names too, but we're mostly just going to talk about IP addresses today.

For example, you're on your phone, you're using Google Maps, it needs to know, where is maps.google.com, right? Or on your computer, where's reddit.com? What's the IP address? And if we didn't have DNS, the entire internet would collapse.

I think it's fun to learn how this behind the scenes stuff works.

The other thing about DNS I find interesting is that it's really old. There's this document (RFC 1035) which defines how DNS works, that was written in 1987. And if you take that document and you write a program that works the way that documents says to work, your program will work. And I think that's kind of wild, right?

The basics haven't changed since before I was born. So if you're a little slow about learning about it, that's ok: it's not going to change out from under you.

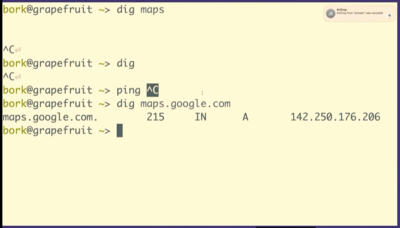

maps.google.com. We

can do that in dig!

dig maps.google.com, it prints out 5 fields. Let's

talk about what those 5 fields are.

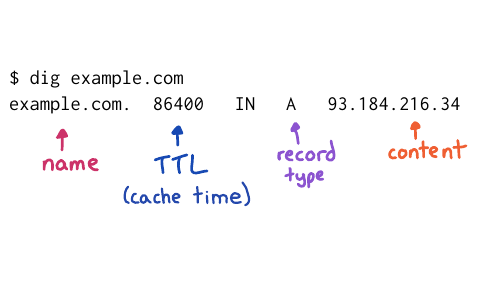

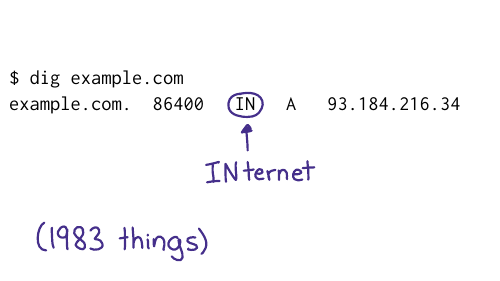

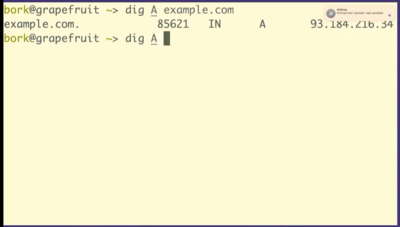

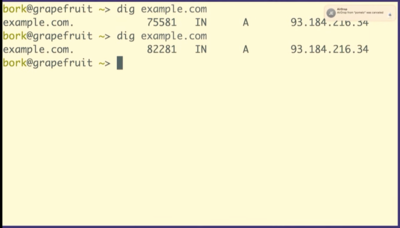

I've used example.com instead of maps.google.com on this slide, but the fields are the same. Let's talk about 4 of them:

We have the domain name, no big deal

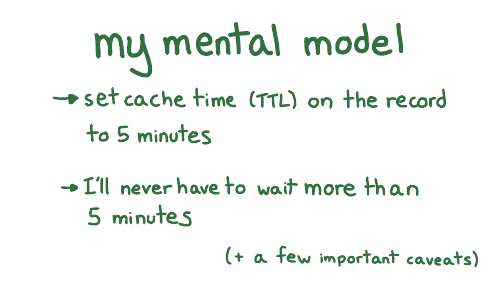

The Time To Live, which is how long to cache that record for so this is a one day

You have the record type, A stands for address because this is an IP address

And you have the content, which is the IP address

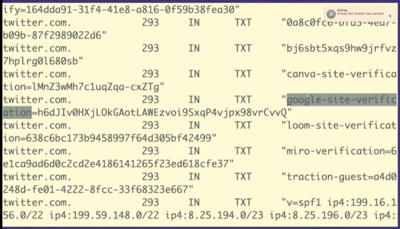

But there are other kinds of records like TXT records. So we're going to look at a TXT record really quickly just because I think this is very fun. We're going to look at twitter.com's TXT records.

So TXT records are something that people use for domain verification, for example to prove to Google that you own twitter.com.

So what you can do is you can set this DNS

record google-site-verification. Google will tell you what to set

it to, you'll set it, and then Google will believe you.

I think it's kind of fun that you can like kind of poke around with DNS and see that Twitter is using Miro or Canva or Mixpanel, that's all public. It's like a little peek into what people are doing inside their companies

+noall +answer and

then your dig responses look much nicer (like they did in the screenshots

above) instead of having a lot of nonsense in them. Whenever possible, I try to

make my tools behave in a more human way.

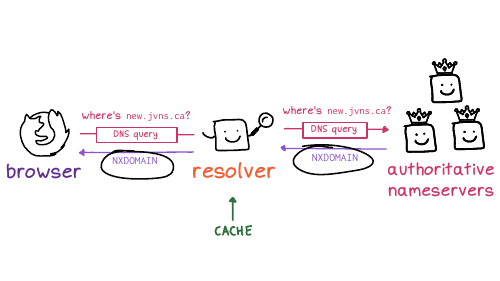

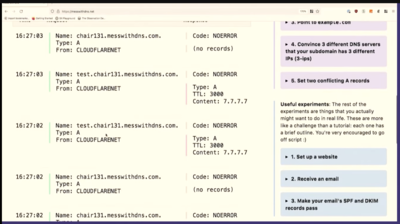

And so here's what it said might be going on. The first time I opened the website (before the DNS records had been set up), the DNS servers returned a negative answer, saying hey,this domain doesn't exist yet. The code for that is NXDOMAIN, which is like a 404 for DNS.

And the resolver cached that negative NXDOMAIN response. So the fact that it didn't exist was cached.

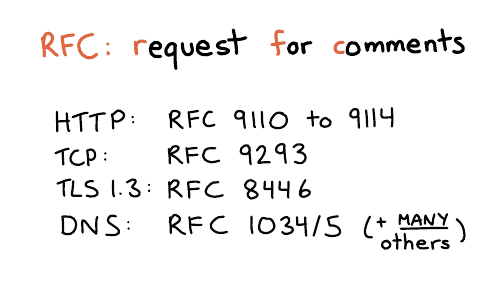

In networking, everything has a specification. The boring technical documents are called RFC is for request for comments. I find this name a bit funny, because for DNS, some of the main RFCs are RFC 1034 and 1035. These were written in 1987, and the comment period ended in 1987. You can definitely no longer make comments. But anyway, that's what they're called.

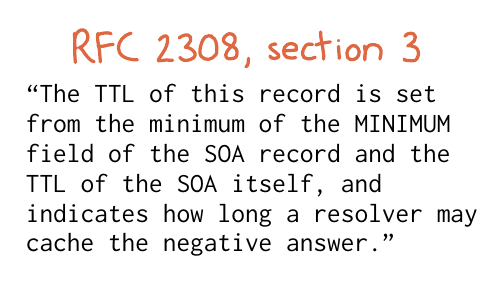

I personally kind of love RFCs because they're like the ultimate answer to many questions. There's a great series of HTTP RFCs, 9110 to 9114. DNS actually has a million different RFCs, it's very upsetting, but the answers are often there. So I went looking. And I think I went looking because when I read comments on StackOverflow, I don't always trust them. How do I know if they're accurate? So I wanted to go to an authoritative source.

So, um, ok, cool. What does that mean, right? Luckily, we only have one question: I don't need to read the entire boring document. I just need to like analyze this one sentence and figure it out.

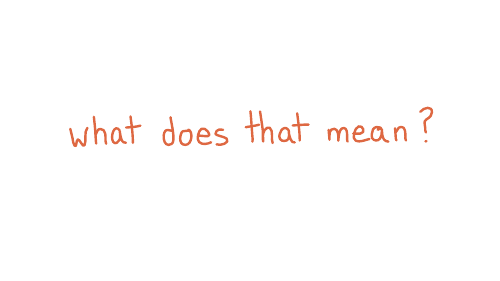

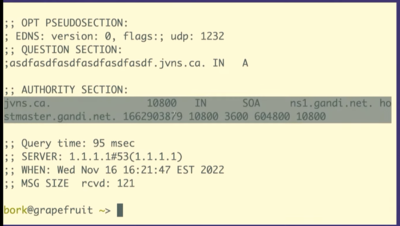

So it's saying that the cache time depends on two fields. I want to show you the actual data it's talking about, the SOA record.

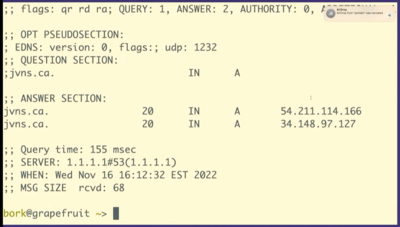

dig +all asdfasdfasdfasdfasdf.jvns.ca

It says that the domain doesn't exist, NXDOMAIN. But it also returns this

record called the SOA record, which has some domain metadata. And there are two

fields here that are relevant.

Here. I put this on a slide to try to make it a little bit clearer. This slide is a bit messed up, but there's this field at the end that's called the MINIMUM field, and there's the TTL, time to live of the record, that I've tried to circle.

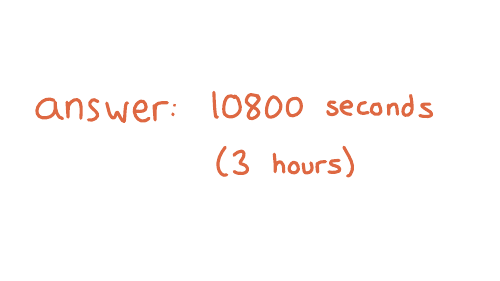

And what it's saying is that if a record doesn't exist, the amount of time the resolver should cache "it doesn't exist" for is the minimum of those two numbers.

And so I waited three hours and then everything worked. And I found this kind of fun to know because often like if you look up DNS advice it will say something like, if something has gone wrong, you need to wait 48 hours. And I do not want to wait 48 hours! I hate waiting. So I love it when I can like use my brain to figure out that I can wait for less time.

Sometimes when I find my mental model is broken, it feels like I don't know anything

But in this case, and I think in a lot of cases, there's often just a few things I'm missing? Like this negative caching thing is like kind of weird, but it really was the one thing I was missing. There are a few more important facts about how DNS caching works that I haven't mentioned, but I haven't run into more problems I didn't understand since then. Though I'm sure there's something I don't know.

So sometimes learning one small thing really can solve all your problems.

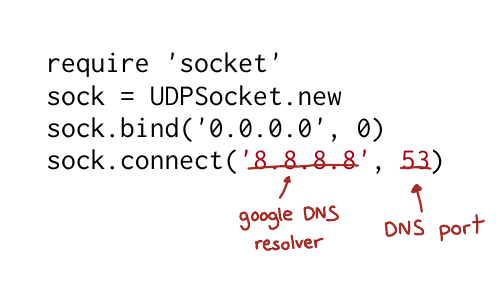

So let's say we want to do some experiments with caching.

I think most people don't want to make experimental changes to their domain names, because they're worried about breaking something. Which I think is very understandable.

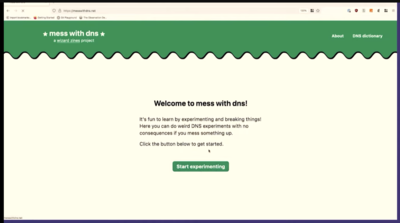

Because I was really into DNS, I wanted to experiment with DNS. And I also wanted other people to experiment with DNS without having to worry about breaking something. So I made this little website with my friend, Marie, called Mess with DNS

The idea is, if you don't want to do that DNS experiments on your domain, you can do them on my domain. And if you mess something up, it's my problem, it's not your problem. And there have been no problems, so that's fine.

So let's use Mess With DNS to do a little DNS experimentation

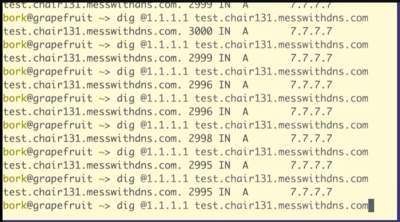

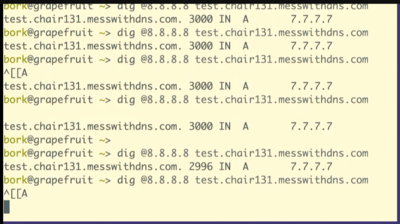

dig @1.1.1.1 test.chair131.messwithdns.com.

I've queried it a bunch of times, maybe 10 or 20.

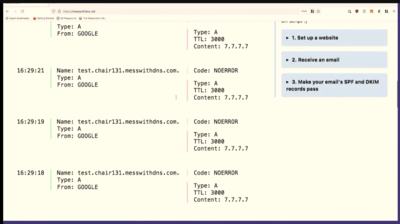

Oh, cool. This isn't what I expected to see. This is fun, though, that's great. We made about 20 queries for that DNS record. The server logs all queries it receives, so we can count them. Our server got 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 queries. That's kind of fun. 8 is less than 20.

One reason I like to do demos live on stage is that sometimes what I what happens isn't exactly what I think will happen. When I do this exact experiment at home, I just get 1 query to the resolver.

So we only saw like eight queries here. And I assume that this is because the resolver, 1.1.1.1, we're talking to has more than one independent cache, I guess there are 8 caches. This makes sense to me because Cloudflare's network is distributed -- the exact machines I'm talking to here in Providence are not the same as the ones in Montreal.

This is interesting because it complicates your idea about how caching works a little bit, right? Like maybe a given DNS resolver actually has like eight caches and which one you get is random, and you're not always talking to the same one. I think that's what's going on here.

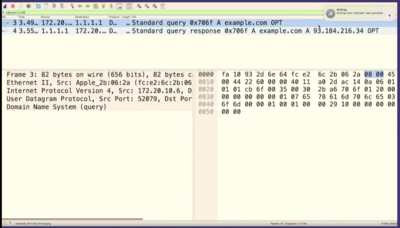

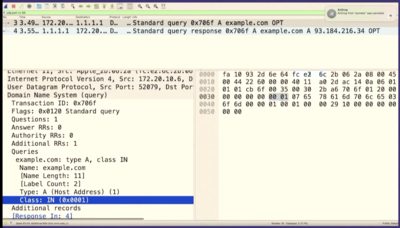

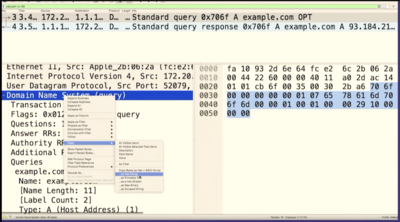

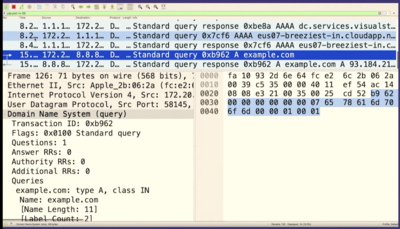

Let's go to Wireshark and look for the packet we just sent. And we can see it there! There's some other noise in between, so I'll stop the capture.

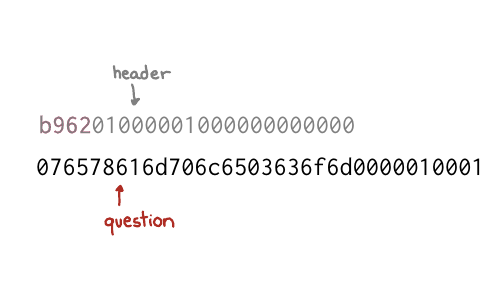

We can see that it's the same packet because the query ID matches, B962.

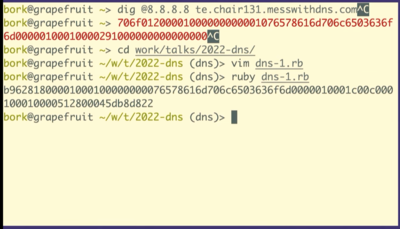

So we sent a query to Google the answer server and we got a response right? It was like this is totally legitimate. There's no problem. It doesn't know that we copied and pasted it and that we have no idea what it means!

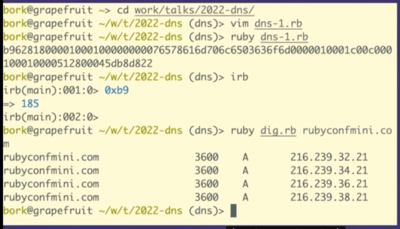

We're going to see how to construct these in Ruby, but first I want to talk about what a byte is for one second. So this (b9) is the hexadecimal representation of a byte. The way I like to look at figure out what that means is just type it into IRB, if you type in 0xB9 it'll print out, that's the number 184.

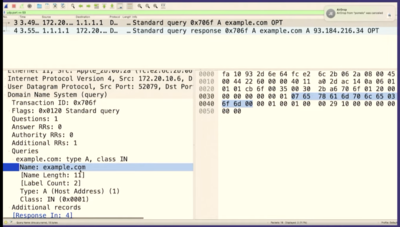

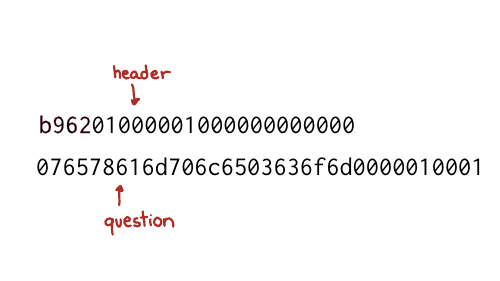

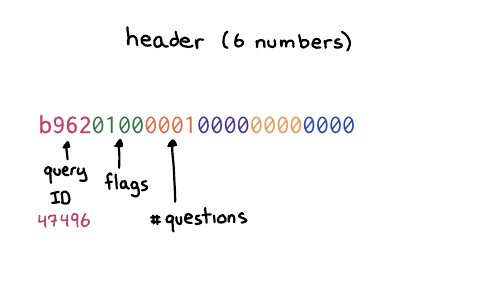

So the question is 12 bytes

b962 which is the query ID. The next number is the flags, which

basically in this case, means like this is a query like hello, I have a

question. And then there's four more sections, the number of questions and then

the number of answers. We do not have any answers. We only have a question. So

we're saying, hello, I have one question. That's what the header means.

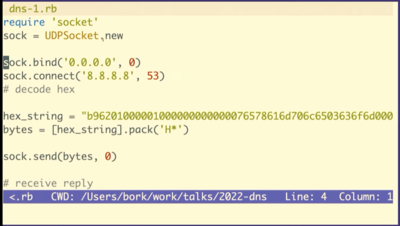

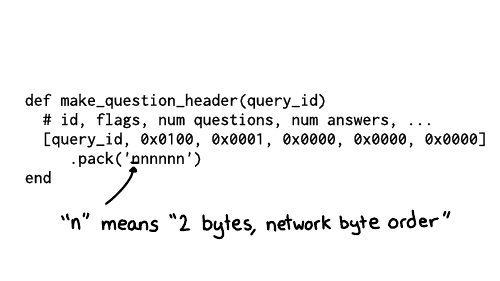

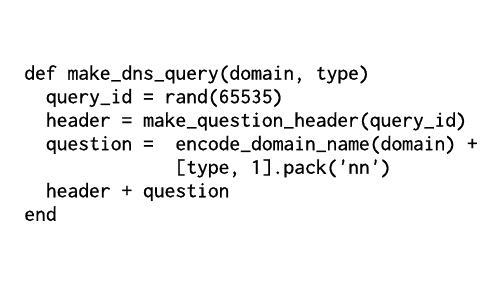

And the way that we can do this in Ruby, is we can make a little array that has the query ID, and then these numbers which correspond to the other the other header fields, the flags and then 1 for 1 question, and then three zeroes for each of the 3 sections of answers.

And then we need to tell Ruby how to take these like six numbers and then represent them as bytes. So n here means each of these is supposed to represent it as two bytes, and it also means to use big endian byte order.

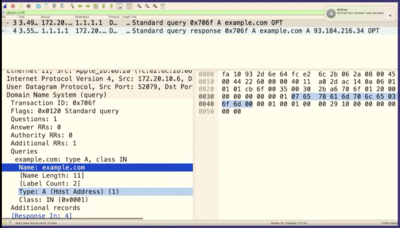

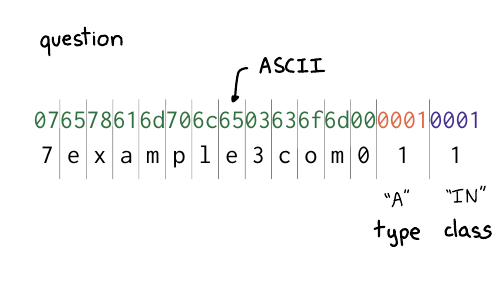

I broke up the question section here. There are two parts

you might recognize from example.com: there's example, and com.

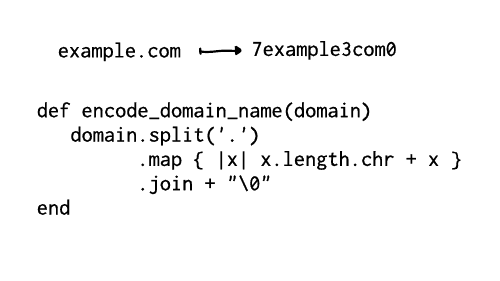

The way it works is that first you have a number (like 7), and then a

7-character string, like "example". The number tells you how many characters to

expect in each part of the domain name. So it's 7, example, 3, com, 0.

And then at the end, you have two more fields for the type and the class. Class 1 is code for "internet". And type 1 is code for "IP address", because we want to look up the IP address. is

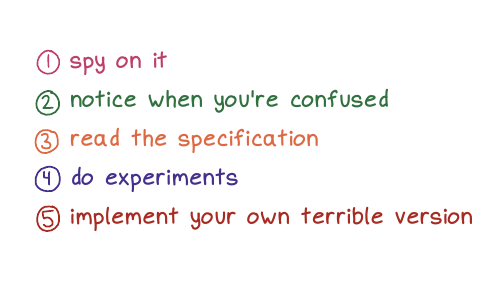

First, spy on it. I find that when I look at things like to see like really what's happening under the hood, and when I look at like, what's in the bytes, you know what's going on? It's often like not as complicated as I think. Like, oh, there's just the domain name and the type. It really makes me feel far more confident that I understand that thing.

I try to notice when I'm confused, and I want to say again, that noticing when you're confused is something that like we don't always have time for right? It's something to do when you have the energy. For example there's this weird DNS query I saw in one of the demos today that I don't understand, but I ignored it because, well, I'm giving a talk. But maybe one day I'll feel like looking at it.

We talked about reading the specification, which, there are few times I feel like more powerful than when I'm in like a discussion with someone, and I KNOW that I have the right answer because, well, I read the specification! It's a really nice way to feel certain.

I love to do experiments to check that my understanding of stuff is right. And often I learn that my understanding of something is wrong! I had an example in this talk that I was going to include and I did an experiment to check that that example was true, and it wasn't! And now I know that. I love that experiments on computers are very fast and cheap and usually have no consequences.

And then the last thing we talked about and truly my favorite, but the most work is like implementing your own terrible version. For me, the confidence I get from writing like a terrible DNS implementation that works on 11 different domain names is unmatched. If my thing works at all, I feel like, wow, you can't tell me that I don't know how DNS works! I implemented it! And it doesn't matter if my implementation is "bad" because I know that it works! I've tested it. I've seen it with my own eyes. And I think that just feels amazing. And there are also no consequences because you're never going to run it in production. So it doesn't matter if it's terrible. It just exists to give you huge amounts of confidence in yourself. And I think that's really nice.

thanks to the organizers!

Thanks to the RubyConf Mini organizers for doing such a great job with the conference – it was the first conference I’d been to since 2019, and I had a great time.

a quick plug for “How DNS Works”

If you liked this talk and want to to spend less than 10 years learning about how DNS works, I spent 6 months condensing everything I know about DNS into 28 pages. It’s here and you can get it for $12: How DNS Works.