Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Making the Web more Awesome — for everyone

Folks, I have some exciting news to share. 🤩

Today I start a new chapter in my career. After a decade at MIT, teaching and doing research at the intersection of usability and programming language design, I wrapped up my PhD two weeks ago (yes, I’m a Dr now! And damn right I will — once it actually sinks in) and today I start my new role as Product Lead at Font Awesome.

I will be evaluating user needs and improving product design and usability across all company products, with an emphasis on Web Awesome, the product we are launching early next year to revolutionize how Web UIs are built by using web components and CSS in ways you’ve never seen before. Beyond improving the products themselves (all of which include extensive free & open source versions), part of my role will utilize my web standards experience to collect web platform pain points from across the company and translating them to new and existing web standards proposals.

Yes, I know, it’s a match made in heaven. 😍

There is even a small chance I may have been the first to create an icon font for use in a web UI via @font-face,

which would make it even more wonderfully poetic that I’m joining the company that has become synonymous with icon fonts on the Web.

However, it was not my MIT PhD that led me to this role, but an email from Dave Gandy (creator & CEO of Font Awesome) about Color.js, that turned into hours of chats, and eventually a job offer for a role I could not refuse, one that was literally molded around my skills and interests.

The role is not the only reason I’m excited to join Font Awesome, though. The company itself is a breath of fresh air: open source friendly (as Dave says, “literally the only reason we have Pro versions is that we need to sustain this somehow” 😅), already profitable (= no scrambling to meet VC demands by cramming AI features nobody wants into our products), fully remote, huge emphasis on work-life balance, and an interview process that did not feel like an interview — or even a process. In fact, they did not even want to look at my resume (despite my efforts 🤣). It is telling that in their 10 years of existence, not a single person has left the company, and they have never had to let anyone go. Moreover, it bridges the best of both worlds: despite having existed for a decade, branching out to new products[1] and markets gives it a startup-like energy and excitement.

I had been extremely selective in the job opportunities I pursued, so it took a while to find the perfect role. Having ADHD (diagnosed only last year — I want to write a blog post about that too at some point), I knew it was crucial to find a job I could be passionate about: ADHD folks are unstoppable machines in jobs they love (I have literally built my career by directing my hyperfocus to things that are actually productive), but struggle way more than neurotypicals in jobs they hate. It took a while, but when I started talking with Dave, I knew Font Awesome was it.

I’m still reeling from the mad rush of spending the past couple of months averaging 100-hour weeks to wrap up my PhD before starting, but I couldn’t be more excited about this new chapter.

I’m hoping to write a series of blog posts in the coming weeks about about my journey to this point. Things like:

- How I decided that academia was not for me — but persisted to the finish line anyway because I’m stubborn AF 😅

- How I realized that product work is my real calling, not software engineering per se (as much as I love both)

- How I used web technologies instead of LaTeX to write my PhD thesis (and print it to PDF for submission), with 11ty plus several open source plugins, many of which I wrote, an ecosystem I hope to one day free more people from the tyranny of LaTeX (which was amazing in the 70s, but its ergonomics are now showing their age).

But for now, I just wanted to share the news, and go off to make the web more awesome — for everyone. 🚀

My excitement grew even stronger when a week before my start date, I learned that 11ty (and its creator, Zach Leatherman) had also joined Font Awesome — I think at this point every tool I use regularly is officially Awesome 😅. Yes, this site is built on 11ty as well. And even my PhD thesis! ↩︎

Forget “show, don’t tell”. Engage, don’t show!

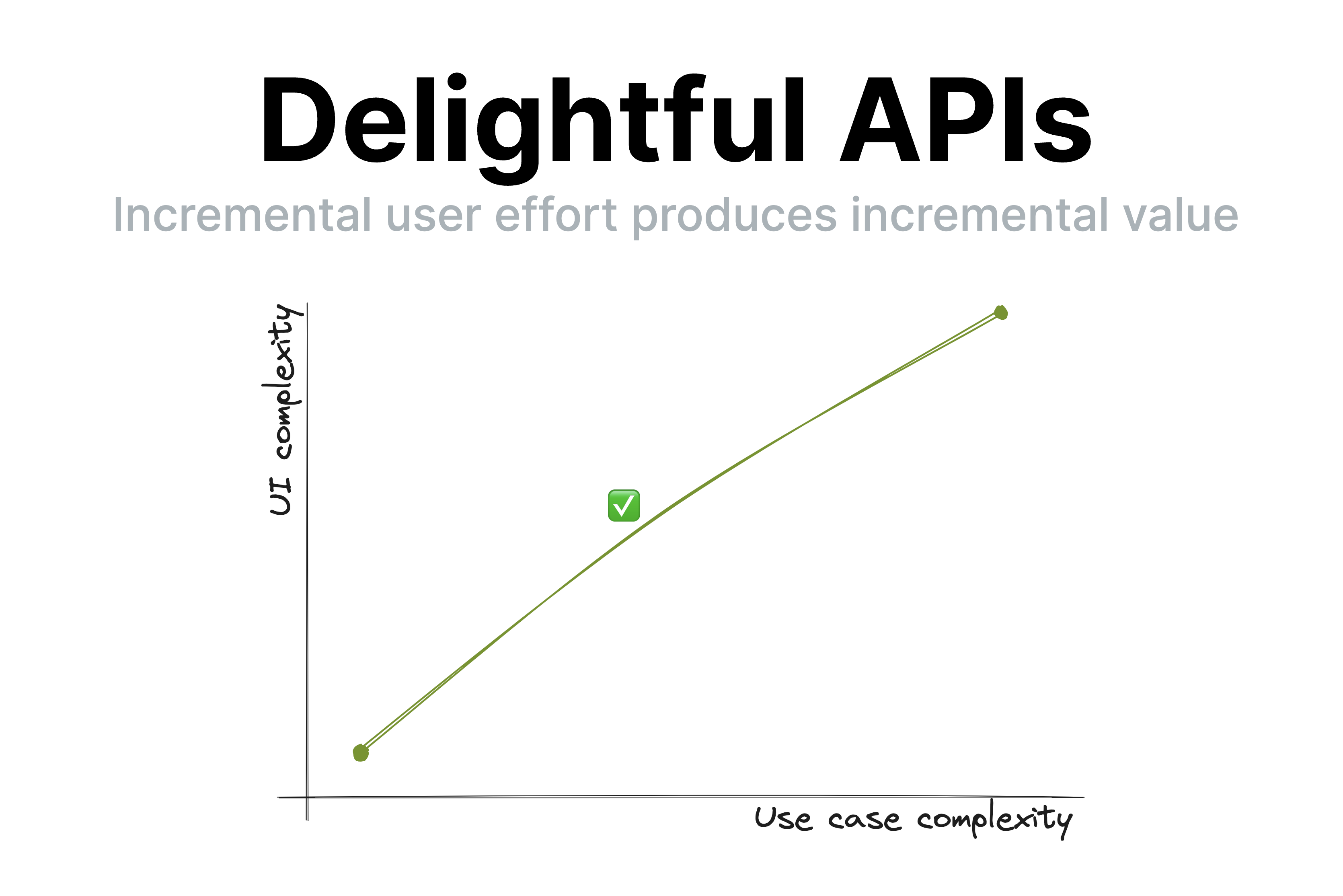

A few days ago, I gave a very well received talk about API design at dotJS titled “API Design is UI Design” [1]. One of the points I made was that good UIs (and thus, good APIs) have a smooth UI complexity to Use case complexity curve. This means that incremental user effort results in incremental value; at no point going just a little bit further requires a disproportionately big chunk of upfront work [2].

Observing my daughter’s second ever piano lesson today made me realize how this principle extends to education and most other kinds of knowledge transfer (writing, presentations, etc.). Her (generally wonderful) teacher spent 40 minutes teaching her notation, longer and shorter notes, practicing drawing clefs, etc. Despite his playful demeanor and her general interest in the subject, she was clearly distracted by the end of it.

It’s easy to dismiss this as a 5 year old’s short attention span, but I could tell what was going on: she did not understand why these were useful, nor how they connect to her end goal, which is to play music. To her, notation was just an assortment of arbitrary symbols and lines, some of which she got to draw. Note lengths were just isolated sounds with no connection to actual music. Once I connected note lengths to songs she has sung with me and suggested they try something more hands on, her focus returned instantly.

I mentioned to her teacher that kids that age struggle to learn theory for that long without practicing it. He agreed, and said that many kids are motivated to get through the theory because they’ve heard their teacher play nice music and want to get there too. The thing is… sure, that’s motivating. But as far as motivations go, it’s pretty weak.

Humans are animals, and animals don’t play the long game, or they would die. We are programmed to optimize for quick, easy dopamine hits. The farther into the future the reward, the more discipline it takes to stay motivated and put effort towards it. This applies to all humans, but even more to kids and ADHD folks [3]. That’s why it’s so hard for teenagers to study so they can improve their career opportunities and why you struggle to eat well and exercise so you can be healthy and fit.

So how does this apply to knowledge transfer? It highlights how essential it is for students to a) understand why what they are learning is useful and b) put it in practice ASAP. You can’t retain information that is not connected to an obvious purpose [4] — your brain will treat it as noise and discard it.

The thing is, the more expert you are on a topic, the harder these are to do when conveying knowledge to others. I get it. I’ve done it too. First, the purpose of concepts feels obvious to you, so it’s easy to forget to articulate it. You overestimate the student’s interest in the minutiae of your field of expertise. Worse yet, so many concepts feel essential that you are convinced nothing is possible without learning them (or even if it is, it’s just not The Right Way™). Looking back on some of my earlier CSS lectures, I’ve definitely been guilty of this.

As educators, it’s very tempting to say “they can’t possibly practice before understanding X, Y, Z, they must learn it properly”. Except …they won’t. At best they will skim over it until it’s time to practice, which is when the actual learning happens. At worst, they will give up. You will get much better retention if you frequently get them to see the value of their incremental imperfect knowledge than by expecting a big upfront attention investment before they can reap the rewards.

There is another reason to avoid long chunks of upfront theory: humans are goal oriented. When we have a goal, we are far more motivated to absorb information that helps us towards that goal. The value of the new information is clear, we are practicing it immediately, and it is already connected to other things we know.

This means that explaining things in context as they become relevant is infinitely better for retention and comprehension than explaining them upfront. When knowledge is a solution to a problem the student is already facing, its purpose is clear, and it has already been filtered by relevance. Furthermore, learning it provides immediate value and instant gratification: it explains what they are experiencing or helps them achieve an immediate goal.

Even if you don’t teach, this still applies to you. I would go as far as to say it applies to every kind of knowledge transfer: teaching, writing documentation, giving talks, even just explaining a tricky concept to your colleague over lunch break. Literally any activity that involves interfacing with other humans benefits from empathy and understanding of human nature and its limitations.

To sum up:

- Always explain why something is useful. Yes, even when it’s obvious to you.

- Minimize the amount of knowledge you convey before the next opportunity to practice it. For non-interactive forms of knowledge transfer (e.g. a book), this may mean showing an example, whereas for interactive ones it could mean giving the student a small exercise or task. Even in non-interactive forms, you can ask questions — the receiver will still pause and think what they would answer even if you are not there to hear it.

- Prefer explaining in context rather than explaining upfront.

“Show, don’t tell”? Nah. More like “Engage, don’t show”.

(In the interest of time, I’m posting this without citations to avoid going down the rabbit hole of trying to find the best source for each claim, especially since I believe they’re pretty uncontroversial in the psychology / cognitive science literature. That said, I’d love to add references if you have good ones!)

The video is now available on YouTube: API Design is UI Design ↩︎

When it does, this is called a usability cliff. ↩︎

I often say that optimizing UX for people with ADHD actually creates delightful experiences even for those with neurotypical attention spans. Just because you could focus your attention on something you don’t find interesting doesn’t mean you enjoy it. Yet another case of accessibility helping everyone! ↩︎

I mean, you can memorize anything if you try hard enough, but by optimizing teaching we can keep rote memorization down to the bare minimum. ↩︎

Inline conditionals in CSS, now?

The CSS WG resolved to add if() to CSS, but that won’t be in browsers for a while.

What are our options in the meantime?

A couple days ago, I posted about the recent CSS WG resolution to add an if() function to CSS.

Great as it may be, this is still a long way off, two years if everything goes super smoothly, more if not.

So what can you do when you need conditionals right now?

You may be pleased to find that you’re not completely out of luck. There is a series of brilliant, horrible hacks that enable you to expose the kinds of higher level custom properties that conditionals typically enable.

Using hacks in production?!

The instinctive reaction many developers have when seeing hacks like these is “Nice hack, but can’t possibly ever use this in production”. This sounds reasonable on the surface (keeping the codebase maintainable is a worthy goal!) but when examined deeply, it reflects the wrong order of priorities, prioritizing developer convenience over user convenience.

The TAG maintains a Web Platform Design Principles document [1] that everyone designing APIs for the web platform is supposed to read and follow. I’m a strong believer in having published Design Principles, for any product[2]. They help stay on track, and remember what the big picture vision is, which is otherwise easy to lose sight of in the day to day minutiae. One of the core principles in the document is the Priority of Constituencies. The core of it is:

User needs come before the needs of web page authors, which come before the needs of user agent implementors, which come before the needs of specification writers, which come before theoretical purity.

Obviously in most projects there are far fewer stakeholders than for the whole web platform, but the spirit of the principle still applies: the higher the abstraction, the higher priority the user needs. Or, in other words, consumers above producers.

For a more relatable example, in a web app using a framework like e.g. Vue and several Vue components, the user needs of website users come before the needs of the web app developers, which come before the needs of the developers of its Vue components, which come before the needs of the Vue framework developers (sorry Evan :).

The TAG did not invent this principle; it is well known in UX and Product circles with a number of different wordings:

- “Put the pain on those who can bear it”

- Prefer internal complexity over external complexity

Why is that? Several reasons:

- It is far easier to change the implementation than to change the user-facing API, so it’s worth making sacrifices to keep it clean from the get go.

- Most products have way more users than developers, so this minimizes collective pain.

- Internal complexity can be managed far more easily, with tooling or even good comments.

- Managing complexity internally localizes it and contains it better.

- Once the underlying platform improves, only one codebase needs to be changed to reap the benefits.

The corollary is that if hacks allow you to expose a nicer API to component users, it may be worth the increase in internal complexity (to a degree). Just make sure that part of the code is well commented, and keep track of it so you can return to it once the platform has evolved to not require a hack anymore.

Like all principles, this isn’t absolute. A small gain in user convenience is not a good tradeoff when it requires tremendous implementation complexity. But it’s a good north star to follow.

As to whether custom properties are a better option to control styling than e.g. attributes, I listed several arguments for that in my previous article. Although, there are also cases where using custom properties is not a good idea…

When is it not a good idea to do this?

In a nutshell, when the abstraction is likely to leak. Ugliness is only acceptable if it’s encapsulated and not exposed to component users. If there is a high chance they may come into contact with it, it might be a better idea to simply use attributes and call it a day.

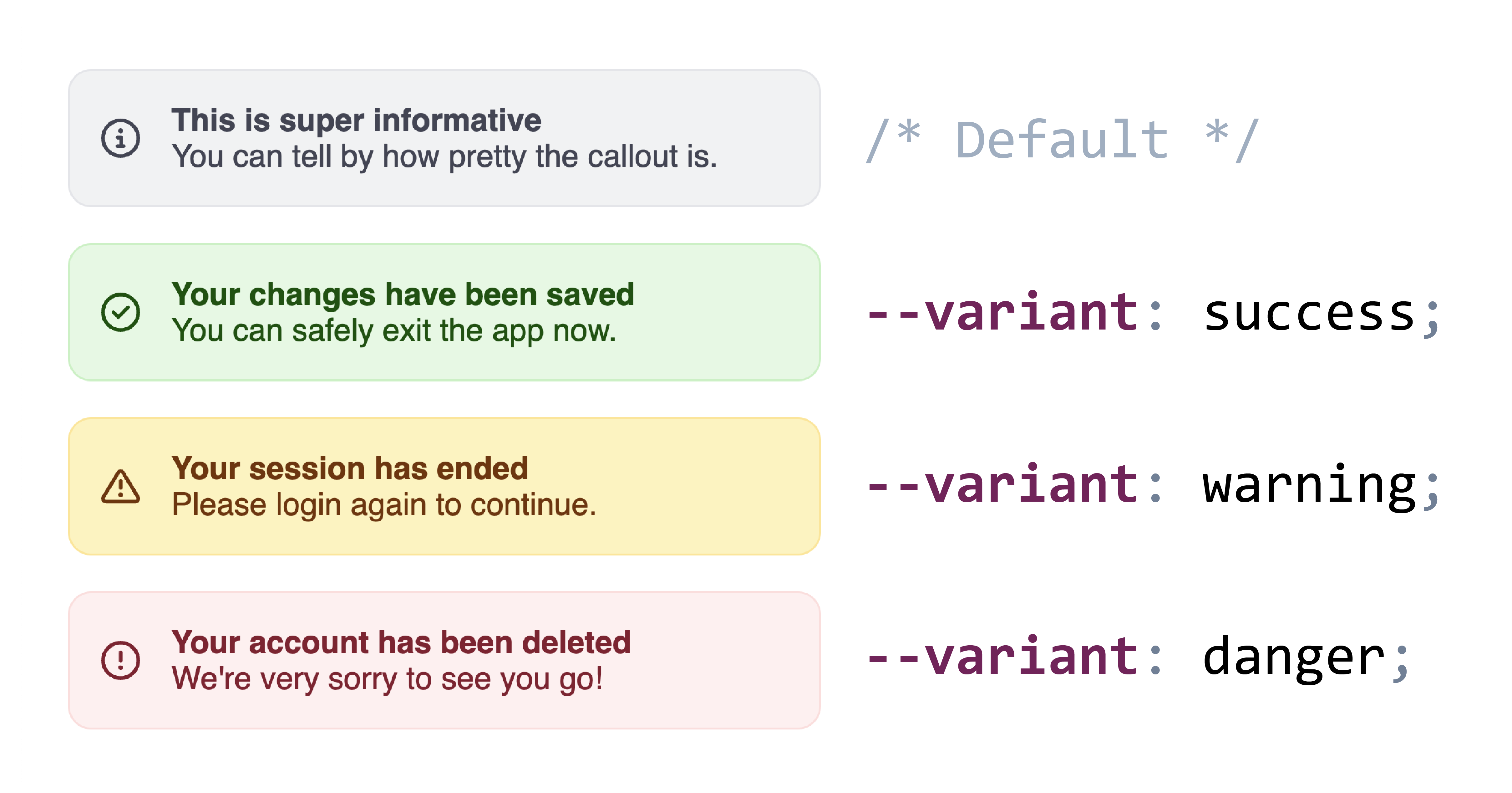

In many of the examples below, I use variants as the canonical example of a custom property that a component may want to expose.

However, if component consumers may need to customize each variant, it may be better to use attributes so they can just use e.g. [variant="success"] instead of having to understand whatever crazy hack was used to expose a --variant custom property.

And even from a philosophical purity perspective, variants are on the brink of presentational vs semantic anyway.

The current state of the art

There is a host of hacks and workarounds that people have come up with to make up for the lack of inline conditionals in CSS, with the first ones dating back to as early as 2015.

1. Binary Linear Interpolation

This was first documented by Roma Komarov in 2016, and has since been used in a number of creative ways.

The gist of this method is to use essentially the linear interpolation formula for mapping

However, instead of using this to map a range to another range,

we use it to map two points to two other points,

basically the two extremes of both ranges:

This was Roma’s original example:

:root {

--is-big: 0;

}

.is-big {

--is-big: 1;

}

.block {

padding: calc(

25px * var(--is-big) +

10px * (1 - var(--is-big))

);

border-width: calc(

3px * var(--is-big) +

1px * (1 - var(--is-big))

);

}

He even expands it to multiple conditions by multiplying the interpolation factors.

E.g. this code snippet to map 0 to 100px, 1 to 20px, and 2 to 3px:

.block {

padding: calc(

100px * (1 - var(--foo)) * (2 - var(--foo)) * 0.5 +

20px * var(--foo) * (2 - var(--foo)) +

3px * var(--foo) * (1 - var(--foo)) * -0.5

);

}

Which these days could be rewritten as this, which also makes the boolean logic at play clearer:

.block {

--if-not-0: min(max(0 - var(--foo), var(--foo) - 0), 1);

--if-not-1: min(max(1 - var(--foo), var(--foo) - 1), 1);

--if-not-2: min(max(2 - var(--foo), var(--foo) - 2), 1);

--if-0: var(--if-not-1) * var(--if-not-2);

--if-1: var(--if-not-0) * var(--if-not-2);

--if-2: var(--if-not-0) * var(--if-not-1);

padding: calc(

100px * var(--if-0) +

20px * var(--if-1) +

3px * var(--if-2)

);

}

Back then, min() and max() were not available, so he had to divide each factor by an obscure constant to make it equal to 1 when it was not 0.

Once abs() ships this will be even simpler (the inner max() is basically getting the absolute value of N - var(--foo))

Ana Tudor also wrote about this in 2018, in this very visual article: DRY Switching with CSS Variables. Pretty sure she was also using boolean algebra on these too (multiplication = AND, addition = OR), but I couldn’t find the exact post.

2. Toggles (Space Toggle, Cyclic Toggles)

This was independently discovered by Ana Tudor (c. 2017), Jane Ori in April 2020 (who gave it the name “Space Toggle”), David Khoursid (aka David K Piano) in June 2020 (he called it prop-and-lock), and yours truly in Oct 2020 (I called it the --var: ; hack, arguably the worst name of the three 😅).

The core idea is that var(--foo, fallback) is actually a very limited form of conditional: if --foo is initial (or IACVT), it falls back to fallback, otherwise it’s var(--foo).

Furthermore, we can set custom properties (or their fallbacks) to empty values to get them to be ignored when used as part of a property value.

It looks like this:

:root {

--if-success: ;

--if-warning: ;

}

.success {

--if-success: initial;

}

.warning {

--if-warning: initial;

}

.callout {

background:

var(--if-success, var(--color-success-90))

var(--if-warning, var(--color-warning-90));

}

One of the downsides of this version is that it only supports two states per variable.

Note how we needed two variables for the two states.

Another downside is that there is no way to specify a fallback if none of the relevant variables are set.

In the example above, if neither --if-success nor --if-warning are set, the background declaration will be empty, and thus become IACVT which will make it transparent.

Cyclic Toggles

In 2023, Roma Komarov expanded the technique into what he called “Cyclic Dependency Space Toggles” which

addresses both limitations:

it supports any number of states,

and allows for a default value.

The core idea is that variables do not only become initial when they are not set, or are explicitly set to initial,

but also when cycles are encountered.

Roma’s technique depends on this behavior by producing cycles on all but one of the variables used for the values. It looks like this:

.info {

--variant: var(--variant-default);

--variant-default: var(--variant,);

--variant-success: var(--variant,);

--variant-warning: var(--variant,);

--variant-error: var(--variant,);

background:

var(--variant-default, lavender)

var(--variant-success, palegreen)

var(--variant-warning, khaki)

var(--variant-error, lightpink);

}

And is used like this:

.my-warning {

--variant: var(--variant-warning);

}

A downside of this method is that since the values behind the --variant-success, --variant-warning, etc variables are specific to the --variant variable

they need to be namespaced to avoid clashes.

Layered Toggles

A big downside of most of these methods (except for the animation-based ones) is that you need to specify all values of the property in one place, and the declaration gets applied whether your custom property has a value or not, which makes it difficult to layer composable styles leading to some undesirable couplings.

Roma Komarov’s “Layered Toggles” method addresses this for some cases

by allowing us to decouple the different values by taking advantage of Cascade Layers.

The core idea is that Cascade Layers include a revert-layer keyword that will cause the current layer to be ignored wrt the declaration it’s used on.

Given that we can use unnamed layers, we can simply user a @layer {} rule for every block of properties we want to apply conditionally.

This approach does have some severe limitations which made it rather unpractical for my use cases. The biggest one is that anything in a layer has lower priority than any unlayered styles, which makes it prohibitive for many use cases. Also, this doesn’t really simplify cyclic toggles, you still need to set all values in one place. Still, worth a look as there are some use cases it can be helpful for.

3. Paused animations

The core idea behind this method is that paused animations (animation-play-state: paused) can still be advanced by setting animation-delay to a negative value.

For example in an animation like animation: 100s foo, you can access the 50% mark by setting animation-delay: -50s.

It’s trivial to transform raw numbers to <time> values, so this can be abstracted to plain numbers for the user-facing API.

Here is a simple example to illustrate how this works:

@keyframes color-mixin {

0% { background: var(--color-neutral-90); border-color: var(--color-neutral-80); }

25% { background: var(--color-success-90); border-color: var(--color-success-80); }

50% { background: var(--color-warning-90); border-color: var(--color-warning-80); }

75% { background: var(--color-danger-90); border-color: var(--color-danger-80); }

}

button {

animation: foo 100s calc(var(--variant) * -100s / 4 ) infinite paused;

}

Used like:

.error button {

--variant: 2;

}

This is merely to illustrate the core idea, having a --variant property that takes numbers is not a good API!

Though the numbers could be aliased to variables, so that users would set --variant: var(--success).

This technique seems to have been first documented by me in 2015, during a talk about …pie charts (I would swear I showed it in an earlier talk but I cannot find it). I never bothered writing about it, but someone else did, 4 years later.

To ensure you don’t get slightly interpolated values due to precision issues, you could also slap a steps() in there:

button {

animation: foo 100s calc(var(--variant) * -100s / 4 ) infinite paused steps(4);

}

This is especially useful when 100 divided by your number of values produces repeating decimals,

e.g. 3 steps means your keyframes are at increments of 33.33333%.

A benefit of this method is that defining each state is done with regular declarations, not involving any weirdness, and that .

It does also have some obvious downsides:

- Values restricted to numbers

- Takes over the

animationproperty, so you can’t use it for actual animations.

4. Type Grinding

So far all of these methods impose constraints on the API exposed by these custom properties: numbers by the linear interpolation method and weird values that have to be hidden behind variables for the space toggle and cyclic toggle methods.

In October 2022, Jane Ori was the first one to discover a method that actually allows us to support plain keywords, which is what the majority of these use cases needs. She called it “CSS-Only Type Grinding”.

Its core idea is if a custom property is registered (via either @property or CSS.registerProperty()),

assigning values to it that are not valid for its syntax makes it IACVT (Invalid at computed value time) and it falls back to its initial (or inherited) value.

She takes advantage of that to progressively transform keywords to other keywords or numbers through a series of intermediate registered custom properties, each substituting one more value for another.

I was recently independently experimenting with a similar idea.

It started from a use case of one of my components where I wanted to implement a --size property with two values: normal and large.

Style queries could almost get me there, but I also needed to set flex-flow: column on the element itself when --size was large.

The end result takes N + 1 @property rules, where N is the number of distinct values you need to support.

The first one is the rule defining the syntax of your actual property:

@property --size {

syntax: "normal | large",

initial-value: normal;

inherits: true;

}

Then, you define N more rules, each progressively substituting one value for another:

@property --size-step-1 {

syntax: "row | large";

initial-value: row;

inherits: false;

}

@property --size-step-end {

syntax: "row | column";

initial-value: column;

inherits: false;

}

And at the component host you daisy chain them like this:

:host {

--size-step-1: var(--size);

--size-step-end: var(--size-step-1);

flex-flow: var(--size-step-end);

}

And component consumers get a really nice API:

.my-component {

--size: large;

}

You can see it in action in this codepen:

See the Pen Transform keywords to other keywords (2 keyword version) by Lea Verou (@leaverou) on CodePen.

You can use the same general idea to transform more keywords or to transform keywords into different sets of keywords for use in different properties.

We can also transform keywords to numbers, by replacing successive keywords with <integer> in the syntax, one at a time, with different initial values each time.

Here is the --variant example using this method:

@property --variant {

syntax: "none | success | warning | danger";

initial-value: none;

inherits: true;

}

@property --variant-step-1 {

syntax: "none | <integer> | warning | danger";

initial-value: 1;

inherits: false;

}

@property --variant-step-2 {

syntax: "none | <integer> | danger";

initial-value: 2;

inherits: false;

}

@property --variant-step-3 {

syntax: "none | <integer>";

initial-value: 3;

inherits: false;

}

@property --variant-index {

syntax: "<integer>";

initial-value: 0;

inherits: false;

}

.callout {

--variant-step-1: var(--variant);

--variant-step-2: var(--variant-step-1);

--variant-step-3: var(--variant-step-2);

--variant-index: var(--variant-step-3);

/* Now use --variant-index to set other values */

}

Then, we can use techniques like linear range mapping to transform it to a length or a percentage (generator)

or recursive color-mix() to use that number to select an appropriate color.

5. Variable animation name

In 2018, Roma Komarov discovered another method that allows plain keywords to be used as the custom property API,

forgot about it, then rediscovered it in June 2023 😅.

He still never wrote about it, so these codepens are the only documentation we have.

It’s a variation of the previous method: instead of using a single @keyframes rule and switching between them via animation-delay,

define several separate @keyframes rules, each named after the keyword we want to use:

@keyframes success {

from, to {

background-color: var(--color-success-90);

border-color: var(--color-success-80);

}

}

@keyframes warning {

from, to {

background-color: var(--color-warning-90);

border-color: var(--color-warning-80);

}

}

@keyframes danger {

from, to {

background-color: var(--color-danger-90);

border-color: var(--color-danger-80);

}

}

.callout {

padding: 1em;

margin: 1rem;

border: 3px solid var(--color-neutral-80);

background: var(--color-neutral-90);

animation: var(--variant) 0s paused both;

}

Used like:

.warning {

--variant: warning;

}

The obvious downsides of this method are:

- Impractical to use outside of Shadow DOM due to the potential for name clashes.

- Takes over the

animationproperty, so you can’t use it for actual animations.

Improvements

Every one of these methods has limitations, some of which are inerent in its nature, but others can be improved upon. In this section I will discuss some improvements that me or others have thought of. I decided to include these in a separate section, since they affect more than one method.

Making animation-based approaches cascade better

A big downside with the animation-based approaches (3 and 5) is the place of animations in the cascade:

properties applied via animation keyframes can only be overridden via other animations or !important.

One way to deal with that is to set custom properties in the animation keyframes, that you apply in regular rules. To use the example from Variable animation name:

@keyframes success {

from, to {

--background-color: var(--color-success-90);

--border-color: var(--color-success-80);

}

}

@keyframes warning {

from, to {

--background-color: var(--color-warning-90);

--border-color: var(--color-warning-80);

}

}

@keyframes danger {

from, to {

--background-color: var(--color-danger-90);

--border-color: var(--color-danger-80);

}

}

.callout {

padding: 1em;

margin: 1rem;

border: 3px solid var(--border-color, var(--color-neutral-80));

background-color: var(--background-color, var(--color-neutral-90));

animation: var(--variant) 0s paused both;

}

Note that you can combine the two approaches (variable animation-name and paused animations)

when you have two custom properties where each state of the first corresponds to N distinct states of the latter.

For example, a --variant that sets colors, and a light/dark mode within each variant that sets different colors.

Making animation-based approaches compose better with author code

Another downside of the animation-based approaches is that they take over the animation property.

If authors want to apply an animation to your component, suddenly a bunch of unrelated things stop working, which is not great user experience.

There isn’t that much to do here to prevent this experience, but you can at least offer a way out:

instead of defining your animations directly on animation, define them on a custom property, e.g. --core-animations.

Then, if authors want to apply their own animations, they just make sure to also include var(--core-animations) before or after.

Discrete color scales

Many of the approaches above are based on numerical values, which are then mapped to the value we actually want. For numbers or dimensions, this is easy. But what about colors?

I linked to Noah Liebman’s post above on recursive color-mix(),

where he presents a rather complex method to select among a continuous color scale based on a 0-1 number.

However, if you don’t care about any intermediate colors and just want to select among a few discrete colors, the method can be a lot simpler. Simple enough to be specified inline.

Let me explain: Since color-mix() only takes two colors, we need to nest them to select among more than 2, no way around that.

However, the percentages we calculate can be very simple: 100% when we want to select the first color and 0% otherwise.

I plugged these numbers into my CSS range mapping tool

(example) and noticed a pattern:

If we want to output 100% when our variable (e.g. --variant-index) is N-1 and 0% when it’s N, we can use 100% * (N - var(--variant-index)).

We can use this on every step of the mixing:

background: color-mix(in oklab,

var(--stone-2) calc(100% * (1 - var(--color-index, 0))), /* default color */

color-mix(in oklab,

var(--green-2) calc(100% * (2 - var(--color-index))),

color-mix(in oklab,

var(--yellow-2) calc(100% * (3 - var(--color-index))),

var(--red-2)

)

)

);

But what happens when the resulting percentage is < 0% or > 100%?

Generally, percentages outside [0%, 100%] make color-mix() invalid,

which would indicate that we need to take care to keep our percentages within that range (via clamp() or max()).

However, within math functions there is no parse-time range-checking,

so values are simply clamped to the allowed range.

Here is a simple example that you can play with (codepen):

See the Pen Discrete color scales with simpler recursive color-mix() by Lea Verou (@leaverou) on CodePen.

And here is a more realistic one, using the Type Grinding method to transform keywords to numbers, and then using the above technique to select among 4 colors for backgrounds and borders (codepen).

Combining approaches

There are two components to each method: the input values it supports, i.e. your custom property API that you will expose, e.g. numbers, keywords, etc.,

and the output values it supports (<dimension>, keywords, etc.).

Even without doing anything, we can combine methods that support the same type of input values, e.g. Binary Linear Interpolation and Paused animations or Type Grinding and Variable animation names.

If we can transform the input values of one method to the input values of another, we can mix and match approaches to maximize flexibility. For example, we can use type grinding to transform keywords to numbers, and then use paused animations or binary linear interpolation to select among a number of quantitative values based on that number.

- Keywords → Numbers

- Type grinding

- Numbers → Keywords

- We can use paused animations to select among a number of keywords based on a number (which we transform to a negative

animation-delay). - Space toggles → Numbers

- Easy:

--number: calc(0 var(--toggle, + 1)) - Numbers → Space toggles

- Once again, Roma Komarov has come up with a very cool trick: he conditionally applies an animation which interpolates two custom properties from

initialto the empty value and vice versa — basically variable animation names but used on an internal value. Unfortunately a Firefox bug prevents it from working interoperably. He also tried a variant for space toggles but that has even worse compatibility, limited to Chrome only. I modified his idea a bit to use paused animations instead, and it looks like my attempt works on Firefox as well. 🎉

So, which one is better?

I’ve summarized the pros and cons of each method below:

| Method | Input values | Output values | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers | Quantitative |

|

|

|

|

|

Any |

|

|

|

| Numbers | Any |

|

|

|

| Keywords |

Any value supported by the |

|

|

|

| Keywords | Any |

|

|

The most important consideration is the API we want to expose to component users. After all, exposing a nicer API is the whole point of this, right?

If your custom property makes sense as a number without degrading usability

(e.g. --size may make sense as a number, but small | medium | large is still better than 0 | 1 | 2),

then Binary Linear Interpolation is probably the most flexible method to start with,

and as we have seen in Combining approaches section, numbers can be converted to inputs for every other method.

However, in the vast majority of cases I have seen, the north star API is a set of plain, high-level keywords. This is only possible via Type Grinding and Variable animation names.

Between the two, Type Grinding is the one providing the best encapsulation, since it relies entirely on custom properties and does not hijack any native properties.

Unfortunately, the fact that @property is not yet supported in Shadow DOM throws a spanner in the works,

but since these intermediate properties are only used for internal calculations,

we can just give them obscure names and insert them in the light DOM.

On the other hand, @keyframes are not only allowed, but also properly scoped when used in Shadow DOM,

so Variable animation name might be a good choice when you don’t want to use the same keywords for multiple custom properties on the same component

and its downsides are not dealbreakers for your particular use case.

Conclusion

Phew! That was a long one. If you’re aware of any other techniques, let me know so I can add them.

And I think after all of this, if you had any doubt that we need if() in CSS,

the sheer number and horribleness of these hacks must have dispelled it by now. 😅

Thanks to Roma Komarov for reviewing earlier drafts of this article.

Inline conditionals in CSS?

Last week, the CSS WG resolved to add an inline if() to CSS.

But what does that mean, and why is it exciting?

Last week, we had a CSS WG face-to-face meeting in A Coruña, Spain.

There is one resolution from that meeting that I’m particularly excited about:

the consensus to add an inline if() to CSS.

While I was not the first to propose an inline conditional syntax,

I did try and scope down the various nonterminating discussions into an MVP that can actually be implemented quickly,

discussed ideas with implemenators,

and eventually published a concrete proposal and pushed for group resolution.

Quite poetically, the relevant discussion occurred on my birthday, so in a way, I got if() as the most unique birthday present ever. 😀

This also comes to show that proposals being rejected is not the end-all for a given feature.

It is in fact quite common for features to be rejected for several times before they are accepted: CSS Nesting, :has(), container queries were all simply the last iteration in a series of rejected proposals.

if() itself was apparently rejected in 2018 with very similar syntax to what I proposed.

What was the difference? Style queries had already shipped, and we could simply reference the same syntax for conditions (plus media() and supports() from Tab’s @when proposal) whereas in the 2018 proposal how conditions would work was largely undefined.

I posted about this on a variety of social media, and the response by developers has been overwhelmingly positive:

I even had friends from big companies writing to tell me their internal Slacks blew up about it. This proves what I’ve always suspected, and was part of the case I made to the CSS WG: that this is a huge pain point. Hopefully the amount and intensity of positive reactions will help browsers prioritize this feature and add it to their roadmaps earlier rather than later.

Across all these platforms, besides the “I can’t wait for this to ship!” sentiment being most common, there were a few other recurring questions and a fair bit of confusion that I figured were worth addressing.

FAQ

What is if() for? Does it replace style queries?

Quite the opposite — if() complements style queries.

If you can do something with style queries, by all means, use style queries — they are almost certainly a better solution.

But there are things you simply cannot do with style queries.

Let me explain.

The motivating use case was that components (in the broader sense) often need to define higher level custom properties, whose values are not just used verbatim in declarations, but that set unrelated values on a variety of declarations.

For example, consider a --variant custom property (inspired from Shoelace’s variant attribute).

It could look like this:

--variant: success | danger | warning | primary | none;

This needs to set background colors, border colors, text colors, icons, etc. In fact, it’s actual value is not used verbatim anywhere, it is only used to set other values.

Style queries get us halfway there:

.callout { /* or :host if in Shadow DOM */

@container (style(--variant: success)) {

&::before {

content: var(--icon-success);

color: var(--color-success);

}

}

/* (other variants) */

}

However, style queries only work on descendants. We cannot do this:

.callout {

@container (style(--variant: success)) {

border-color: var(--color-success-30);

background-color: var(--color-success-95);

&::before {

content: var(--icon-success);

color: var(--color-success-05);

}

}

/* (other variants) */

}

Often the declarations we need to set on the element itself are very few, sometimes even just one.

However, even one is one too many and makes using custom properties untenable for many (possibly most) higher level custom property use cases.

As a result, component libraries end up resorting to presentational attributes like pill, outline, size, etc.

While presentational attributes may seem fine at first glance, or even better for DX (fewer characters — at least compared to setting a variable per element), they have several usability issues:

- Reduced flexibility

- They cannot be conditionally applied based on selectors, media queries, etc. Changing them requires more JS. If they are used within another component, you’re SOL, whereas with (inheritable) custom properties, you can set the property on the parent component and it will inherit down.

- Verbosity

- They have to be applied to individual instances, and cannot be inherited. Even if one uses some form of templating or componentization to reduce duplication, they still have to wade through these attributes when debugging with dev tools.

- Lack of consistency

- Since almost every mature component also supports custom properties, users have to remember which styling is done via attributes and which via custom properties. The distinction is often arbitrary, as it’s not driven by use cases, but implementation convenience.

With if(), the above example becomes possible, albeit with worse ergonomics than style queries since it cannot cascade

(though I do have a proposal to allow it to — plus all other IACVT declarations):

.callout {

border-color: if(

style(--variant: success) ? var(--color-success-30) :

style(--variant: danger) ? var(--color-danger-30) :

/* (other variants) */

var(--color-neutral-30)

);

background-color: if(

style(--variant: success) ? var(--color-success-95) :

style(--variant: danger) ? var(--color-danger-95) :

/* (other variants) */

var(--color-neutral-95)

);

@container (style(--variant: success)) {

&::before {

content: var(--icon-success);

color: var(--color-success-05);

}

}

/* (other variants) */

}

While this was the primary use case, it turned out that it’s pretty easy to also make media queries and supports conditions part of if()’s conditional syntax.

And since it’s a function, its arguments (including the condition!) can be stored in other custom properties.

This means you can do things like this:

:root {

--xl: media(width > 1600px);

--l: media (width > 1200px);

--m: media (width > 800px);

}

and then define values like:

padding: if(

var(--xl) ? var(--size-3) :

var(--l) or var(--m) ? var(--size-2) :

var(--size-1)

);

Just like ternaries in JS, it may also be more ergonomic for cases where only a small part of the value varies:

animation: if(media(prefers-reduced-motion) ? 10s : 1s) rainbow infinite;

So is it in browsers yet?

Believe it or not, that was a real question I got 😅. No, it’s not in browsers yet, and it won’t be for a while. The most optimistic estimate is 2 years or so, if the process doesn’t stall at any point (as it often does).

All we have is consensus to work on the feature. The next steps are:

- Reach consensus on the syntax of the feature.

Syntax debates can often take a very long time, because syntax is an area where everyone has opinions.

The current debates revolve around:

- What separators to use between the condition and the branches?

- How to represent no value? Do we simply allow empty values like in

var()(where you can dovar(--foo,)) or do we introduce a dedicated syntax that means “empty value”? - Should the last value be optional?

- Spec the feature.

- Get the first implementation. Often that is the hardest part. Once one browser implements, it is far easier to get the others on board.

- Get it shipped across all major browsers.

I do have a page where I track some of my standards proposals which should help illuminate what the timeline looks like for each of these steps.

In fact, you can track the progress of if() specifically there too.

Is this the first conditional in CSS?

Many responses were along the lines of “Wow, CSS is finally getting conditionals!”.

Folks… CSS had conditionals from the very beginning. Every selector is essentially a conditional!

In addition:

@mediaand@supportsrules are conditionals. And let’s not forget@container.var(--foo, fallback)is a limited type of conditional (essentiallyif(style(--foo: initial) ? var(--foo) : fallback)), hence why it’s the basis of most workarounds for emulating inline conditionals.

Does this make CSS imperative?

A widespread misconception is that non-linear logic (conditionals, loops) makes a language imperative.

Declarative vs imperative is not about logic, but level of abstraction. Are we describing the goal or how to achieve it? In culinary terms, a recipe is imperative, a restaurant menu is declarative

Conditional logic can actually make a language more declarative if it helps describe intent better.

Consider the following two snippets of CSS:

| Space toggle | if() |

|---|---|

|

|

I would argue the latter is far more declarative, i.e. much closer to specifying the goal rather than how to achieve it.

Does this make CSS a programming language?

A very common type of response was around whether CSS is now a programming language (either asking whether it is, or asserting that it now is). To answer that, one first needs to answer what a programming language is.

If it’s Turing-completeness that makes a language a programming language, then CSS has been a programming language for over a decade. But then again, so is Excel or Minecraft. So what does that even mean?

If it’s imperativeness, then no, CSS is not a programming language. But neither are many actual programming languages!

But a deeper question is, why does it matter? Is it because it legitimizes choosing to specialize in CSS? It is because you can then be considered a programmer even if you only write HTML & CSS? If this only matters for optics, then we should fix the issue at its core and fight to legitimize CSS expertise regardless of whether CSS is a programming language. After all, as anyone who knows several well-respected programming languages and CSS can attest, CSS is far harder to master.

Great as all this may be, it won’t be in browsers for a while. What can we do right now? I wrote Part 2 exactly about that: CSS Conditionals, now?

On compliance vs readability: Generating text colors with CSS

Can we emulate the upcoming CSS contrast-color() function via CSS features that have already widely shipped?

And if so, what are the tradeoffs involved and how to best balance them?

Relative Colors

Out of all the CSS features I have designed, Relative Colors aka Relative Color Syntax (RCS) is definitely among the ones I’m most proud of. In a nutshell, they allow CSS authors to derive a new color from an existing color value by doing arbitrary math on color components in any supported color space:

--color-lighter: hsl(from var(--color) h s calc(l * 1.2));

--color-lighterer: oklch(from var(--color) calc(l + 0.2) c h);

--color-alpha-50: oklab(from var(--color) l a b / 50%);

The elevator pitch was that by allowing lower level operations they provide authors flexibility on how to derive color variations, giving us more time to figure out what the appropriate higher level primitives should be.

As of May 2024, RCS has shipped in every browser except Firefox. but given that it is an Interop 2024 focus area, that Firefox has expressed a positive standards position, and that the Bugzilla issue has had some recent activity and has been assigned, I am optimistic it would ship in Firefox soon (edit: it shipped 5 days after writing these lines, in Firefox 128 🎉). My guess it that it would become Baseline by the end of 2024.

Even if my prediction is off, it already is available to 83% of users worldwide,

and if you sort its caniuse page by usage,

you will see the vast majority of the remaining 17% doesn’t come from Firefox,

but from older Chrome and Safari versions.

I think its current market share warrants production use today,

as long as we use @supports to make sure things work in non-supporting browsers, even if less pretty.

Most Relative Colors tutorials revolve around its primary driving use cases: making tints and shades or other color variations by tweaking a specific color component up or down, and/or overriding a color component with a fixed value, like the example above. While this does address some very common pain points, it is merely scratching the surface of what RCS enables. This article explores a more advanced use case, with the hope that it will spark more creative uses of RCS in the wild.

The CSS contrast-color() function

One of the big longstanding CSS pain points is that it’s impossible to automatically specify a text color that is guaranteed to be readable on arbitrary backgrounds, e.g. white on darker colors and black on lighter ones.

Why would one need that? The primary use case is when colors are outside the CSS author’s control. This includes:

- User-defined colors. An example you’re likely familiar with: GitHub labels. Think of how you select an arbitrary color when creating a label and GitHub automatically picks the text color — often poorly (we’ll see why in a bit)

- Colors defined by another developer. E.g. you’re writing a web component that supports certain CSS variables for styling. You could require separate variables for the text and background, but that reduces the usability of your web component by making it more of a hassle to use. Wouldn’t it be great if it could just use a sensible default, that you can, but rarely need to override?

- Colors defined by an external design system, like Open Props, Material Design, or even (gasp) Tailwind.

Even in a codebase where every line of CSS code is controlled by a single author, reducing couplings can improve modularity and facilitate code reuse.

The good news is that this is not going to be a pain point for much longer.

The CSS function contrast-color() was designed to address exactly that.

This is not new, you may have heard of it as color-contrast() before, an earlier name.

I recently drove consensus to scope it down to an MVP that addresses the most prominent pain points and can actually ship soonish,

as it circumvents some very difficult design decisions that had caused the full-blown feature to stall.

I then added it to the spec per WG resolution, though some details still need to be ironed out.

Usage will look like this:

background: var(--color);

color: contrast-color(var(--color));

Glorious, isn’t it? Of course, soonish in spec years is still, well, years. As a data point, you can see in my past spec work that with a bit of luck (and browser interest), it can take as little as 2 years to get a feature shipped across all major browsers after it’s been specced. When the standards work is also well-funded, there have even been cases where a feature went from conception to baseline in 2 years, with Cascade Layers being the poster child for this: proposal by Miriam in Oct 2019, shipped in every major browser by Mar 2022. But 2 years is still a long time (and there are no guarantees it won’t be longer). What is our recourse until then?

As you may have guessed from the title, the answer is yes.

It may not be pretty, but there is a way to emulate contrast-color() (or something close to it) using Relative Colors.

Using RCS to automatically compute a contrasting text color

In the following we will use the OKLCh color space, which is the most perceptually uniform polar color space that CSS supports.

Let’s assume there is a Lightness value above which black text is guaranteed to be readable regardless of the chroma and hue, and below which white text is guaranteed to be readable. We will validate that assumption later, but for now let’s take it for granted. In the rest of this article, we’ll call that value the threshold and represent it as Lthreshold.

We will compute this value more rigously in the next section (and prove that it actually exists!),

but for now let’s use 0.7 (70%).

We can assign it to a variable to make it easier to tweak:

--l-threshold: 0.7;

Let’s work backwards from the desired result. We want to come up with an expression that is composed of widely supported CSS math functions, and will return 1 if L ≤ Lthreshold and 0 otherwise. If we could write such an expression, we could then use that value as the lightness of a new color:

--l: /* ??? */;

color: oklch(var(--l) 0 0);

How could we simplify the task?

One way is to relax what our expression needs to return.

We don’t actually need an exact 0 or 1

If we can manage to find an expression that will give us 0 when L > Lthreshold

and > 1 when L ≤ Lthreshold,

we can just use clamp(0, /* expression */, 1) to get the desired result.

One idea would be to use ratios, as they have this nice property where they are > 1 if the numerator is larger than the denominator and ≤ 1 otherwise.

The ratio of

Putting it all together, it looks like this:

--l-threshold: 0.7;

--l: clamp(0, (l / var(--l-threshold) - 1) * -infinity, 1);

color: oklch(from var(--color) var(--l) 0 h);

One worry might be that if L gets close enough to the threshold we could get a number between 0 - 1, but in my experiments this never happened, presumably since precision is finite.

Fallback for browsers that don’t support RCS

The last piece of the puzzle is to provide a fallback for browsers that don’t support RCS.

We can use @supports with any color property and any relative color value as the test, e.g.:

.contrast-color {

/* Fallback */

background: hsl(0 0 0 / 50%);

color: white;

@supports (color: oklch(from red l c h)) {

--l: clamp(0, (l / var(--l-threshold) - 1) * -infinity, 1);

color: oklch(from var(--color) var(--l) 0 h);

background: none;

}

}

In the spirit of making sure things work in non-supporting browsers, even if less pretty, some fallback ideas could be:

- A white or semi-transparent white background with black text or vice versa.

-webkit-text-strokewith a color opposite to the text color. This works better with bolder text, since half of the outline is inside the letterforms.- Many

text-shadowvalues with a color opposite to the text color. This works better with thinner text, as it’s drawn behind the text.

Does this mythical L threshold actually exist?

In the previous section we’ve made a pretty big assumption: That there is a Lightness value (Lthreshold) above which black text is guaranteed to be readable regardless of the chroma and hue, and below which white text is guaranteed to be readable regardless of the chroma and hue. But does such a value exist? It is time to put this claim to the test.

When people first hear about perceptually uniform color spaces like Lab, LCH or their improved versions, OkLab and OKLCH, they imagine that they can infer the contrast between two colors by simply comparing their L(ightness) values. This is unfortunately not true, as contrast depends on more factors than perceptual lightness. However, there is certainly significant correlation between Lightness values and contrast.

At this point, I should point out that while most web designers are aware of the WCAG 2.1 contrast algorithm, which is part of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines and baked into law in many countries, it has been known for years that it produces extremely poor results. So bad in fact that in some tests it performs almost as bad as random chance for any color that is not very light or very dark. There is a newer contrast algorithm, APCA that produces far better results, but is not yet part of any standard or legislation, and there have previously been some bumps along the way with making it freely available to the public (which seem to be largely resolved).

So where does that leave web authors? In quite a predicament as it turns out. It seems that the best way to create accessible color pairings right now is a two step process:

- Use APCA to ensure actual readability

- Compliance failsafe: Ensure the result does not actively fail WCAG 2.1.

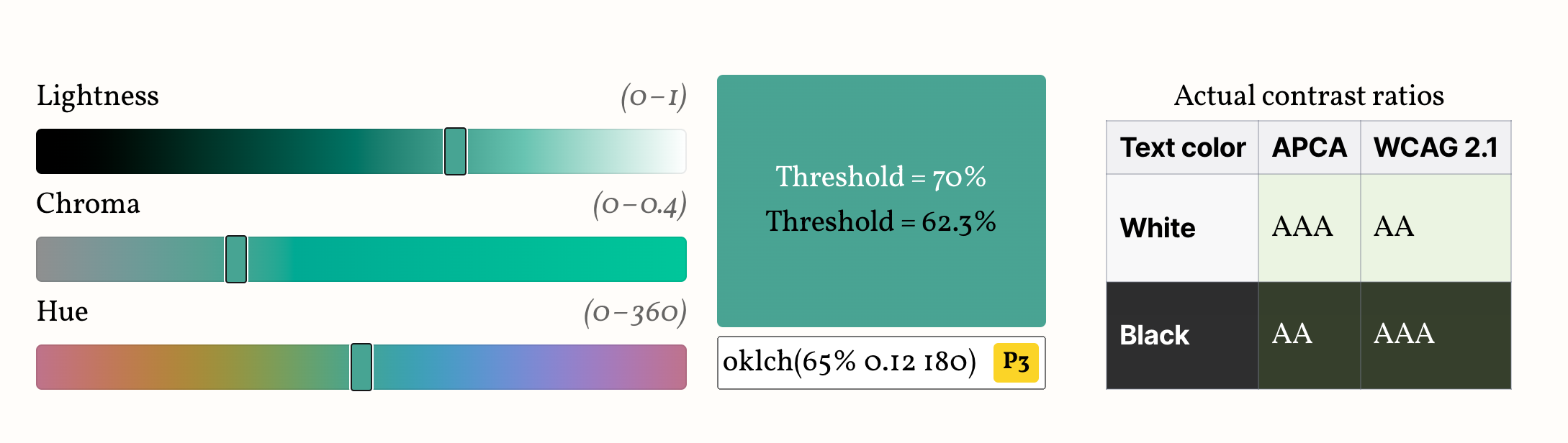

I ran some quick experiments using Color.js where I iterate over the OKLCh reference range (loosely based on the P3 gamut) in increments of increasing granularity and calculate the lightness ranges for colors where white was the “best” text color (= produced higher contrast than black) and vice versa. I also compute the brackets for each level (fail, AA, AAA, AAA+) for both APCA and WCAG.

I then turned my exploration into an interactive playground where you can run the same experiments yourself, potentially with narrower ranges that fit your use case, or with higher granularity.

This is the table produced with C ∈ [0, 0.4] (step = 0.025) and H ∈ [0, 360) (step = 1):

| Text color | Level | APCA | WCAG 2.1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Min | Max | ||

| white | best | 0% | 75.2% | 0% | 61.8% |

| fail | 71.6% | 100% | 62.4% | 100% | |

| AA | 62.7% | 80.8% | 52.3% | 72.1% | |

| AAA | 52.6% | 71.7% | 42% | 62.3% | |

| AAA+ | 0% | 60.8% | 0% | 52.7% | |

| black | best | 66.1% | 100% | 52% | 100% |

| fail | 0% | 68.7% | 0% | 52.7% | |

| AA | 60% | 78.7% | 42% | 61.5% | |

| AAA | 69.4% | 87.7% | 51.4% | 72.1% | |

| AAA+ | 78.2% | 100% | 62.4% | 100% | |

Note that these are the min and max L values for each level. E.g. the fact that white text can fail WCAG when L ∈ [62.4%, 100%] doesn’t mean that every color with L > 62.4% will fail WCAG, just that some do. So, we can only draw meaningful conclusions by inverting the logic: Since all white text failures are have an L ∈ [62.4%, 100%], it logically follows that if L < 62.4%, white text will pass WCAG regardless of what the color is.

By applying this logic to all ranges, we can draw similar guarantees for many of these brackets:

| 0% to 52.7% | 52.7% to 62.4% | 62.4% to 66.1% | 66.1% to 68.7% | 68.7% to 71.6% | 71.6% to 75.2% | 75.2% to 100% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compliance WCAG 2.1 | white | ✅ AA | ✅ AA | |||||

| black | ✅ AA | ✅ AAA | ✅ AAA | ✅ AAA | ✅ AAA | ✅ AAA+ | ||

| Readability APCA | white | 😍 Best | 😍 Best | 😍 Best | 🙂 OK | 🙂 OK | ||

| black | 🙂 OK | 🙂 OK | 😍 Best | |||||

You may have noticed that in general, WCAG has a lot of false negatives around white text, and tends to place the Lightness threshold much lower than APCA. This is a known issue with the WCAG algorithm.

Therefore, to best balance readability and compliance, we should use the highest threshold we can get away with. This means:

- If passing WCAG is a requirement, the highest threshold we can use is 62.3%.

- If actual readability is our only concern, we can safely ignore WCAG and pick a threshold somewhere between 68.7% and 71.6%, e.g. 70%.

Here’s a demo so you can see how they both play out. Edit the color below to see how the two thresholds work in practice, and compare with the actual contrast brackets, shown on the table next to (or below) the color picker.

Your browser does not support Relative Color Syntax, so the demo below will not work.

This is what it looks like in a supporting browser:

| Text color | APCA | WCAG 2.1 |

|---|---|---|

| White | ||

| Black |

Avoid colors marked “P3+”, “PP” or “PP+”, as these are almost certainly outside your screen gamut, and browsers currently do not gamut map properly, so the visual result will be off.

Note that if your actual color is more constrained (e.g. a subset of hues or chromas or a specific gamut), you might be able to balance these tradeoffs better by using a different threshold. Run the experiment yourself with your actual range of colors and find out!

Here are some examples of narrower ranges I have tried and the highest threshold that still passes WCAG 2.1:

| Description | Color range | Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Modern low-end screens | Colors within the sRGB gamut | 65% |

| Modern high-end screens | Colors within the P3 gamut | 64.5% |

| Future high-end screens | Colors within the Rec.2020 gamut | 63.4% |

| Neutrals | C ∈ [0, 0.03] | 67% |

| Muted colors | C ∈ [0, 0.1] | 65.6% |

| Warm colors (reds/oranges/yellows) | H ∈ [0, 100] | 66.8% |

| Pinks/Purples | H ∈ [300, 370] | 67% |

It is particularly interesting that the threshold is improved to 64.5% by just ignoring colors that are not actually displayable on modern screens. So, assuming (though sadly this is not an assumption that currently holds true) that browsers prioritize preserving lightness when gamut mapping, we could use 64.5% and still guarantee WCAG compliance.

You can even turn this into a utility class that you can combine with different thesholds:

.contrast-color {

--l: clamp(0, (l / var(--l-threshold, 0.623) - 1) * -infinity, 1);

color: oklch(from var(--color) var(--l) 0 h);

}

.pink {

--l-threshold: 0.67;

}

Conclusion & Future work

Putting it all together, including a fallback, as well as a “fall forward” that uses contrast-color(),

the utility class could look like this:

.contrast-color {

/* Fallback for browsers that don't support RCS */

color: white;

text-shadow: 0 0 .05em black, 0 0 .05em black, 0 0 .05em black, 0 0 .05em black;

@supports (color: oklch(from red l c h)) {

--l: clamp(0, (l / var(--l-threshold, 0.623) - 1) * -infinity, 1);

color: oklch(from var(--color) var(--l) 0 h);

text-shadow: none;

}

@supports (color: contrast-color(red)) {

color: contrast-color(var(--color));

text-shadow: none;

}

}

This is only a start. I can imagine many directions for improvement such as:

- Since RCS allows us to do math with any of the color components in any color space, I wonder if there is a better formula that still be implemented in CSS and balances readability and compliance even better. E.g. I’ve had some chats with Andrew Somers (creator of APCA) right before publishing this, which suggest that doing math on luminance (the Y component of XYZ) instead could be a promising direction.

- We currently only calculate thresholds for white and black text.

However, in real designs, we rarely want pure black text,

which is why

contrast-color()only guarantees a “very light or very dark color” unless themaxkeyword is used. How would this extend to darker tints of the background color?

Addendum

As often happens, after publishing this blog post, a ton of folks reached out to share all sorts of related work in the space. I thought I’d share some of the most interesting findings here.

Using luminance instead of Lightness

When colors have sufficiently different lightness values (as happens with white or black text), humans disregard chromatic contrast (the contrast that hue/colorfulness provide) and basically only use lightness contrast to determine readability. This is why L can be such a good predictor of whether white or black text works best.

Another measure, luminance, is basically the color’s Y component in the XYZ color space, and a good threshold for flipping to black text is when Y > 0.36. This gives us another method for computing a text color:

--y-threshold: 0.36;

--y: clamp(0, (y / var(--y-threshold) - 1) * -infinity, 1);

color: color(from var(--color) xyz-d65 var(--y) var(--y) var(--y));

As you can see in this demo by Lloyd Kupchanko, using Ythreshold > 36% very closely predicts the best text color as determined by APCA.

In my tests (codepen) it appeared to work as well as the Lthreshold method, i.e. it was a struggle to find colors where they disagree. However, after this blog post, Lloyd added various Lthreshold boundaries to his demo, and it appears that indeed, Lthreshold has a wider range where it disagrees with APCA than Ythreshold does.

Given this, my recommendation would be to use the Ythreshold method if you need to flip between black and white text, and the Lthreshold method if you need to customize the text color further (e.g. have a very dark color instead of black).

Browser bug & workarounds

About a week after publishing this post, I discovered a browser bug with color-mix() and RCS,

where colors defined via color-mix() used in from render RCS invalid.

You can use this testcase to see if a given browser is affected.

This has been fixed in Chrome 125 and Safari TP release 194, but it certainly throws a spanner in the works since the whole point of using this technique is that we don’t have to care how the color was defined.

There are two ways to work around this:

- Adjust the

@supportscondition to usecolor-mix(), like so:

@supports (color: oklch(from color-mix(in oklch, red, tan) l c h)) {

/* ... */

}

The downside is that right now, this would restrict the set of browsers this works in to a teeny tiny set. 2. Register the custom property that contains the color:

@property --color {

syntax: "<color>";

inherits: true;

initial-value: transparent;

}

This completely fixes it, since if the property is registered, by the time the color hits RCS, it’s just a resolved color value.

@property is currently supported by a much wider set of browsers than RCS, so this workaround doesn’t hurt compatiblity at all.

Useful resources

Many people have shared useful resources on the topic, such as:

- Black or White?: Compare different contrast algorithms for picking between black or white

- Dynamic text color contrast based on background lightness with CSS/SVG filters: A different approach to the same problem (requires extra HTML element for the text)

Thanks to Chris Lilley, Andrew Somers, Cory LaViska, Elika Etemad, and Tab Atkins-Bittner for their feedback on earlier drafts of this article.