Thanks to my friends in the Fronteers Slack #accessibility channel for discussing some of this together.

Update 6 December 2021: added “Similar features” section

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

In a Dutch podcast, I heard a prominent tech journalist praise Mark Zuckerberg’s recent Metaverse PR event: finally, the company had presented a grand vision and it looked so cool! In my own tech bubble on Twitter, I saw mostly memes to poke fun at the concept, the presentation and the presenter, and lots of insightful scrutiny.

The COVID pandemic has accelerated the move of work to digital spaces rather than physical ones. Metaverse-enthusiasts often claim that more Metaverse-tech can give us a much better version of digital life. I’m not sure about that.

Though it was refreshing, I will say I was disappointed by the tech journalist’s enthusiasm. Not because Mark Zuckerberg deserves the laughs, or because it somehow scratches an itch ito criticise people who are genuinely trying to make exciting new tech. I mean, maybe… but really, it is because Facebook’s actions prove time over time they require scrutiny. This corporation makes decisions that put their profit above the safety of both people and the societies they live in, and it plays innocent through a clever PR apparatus (see my post on An Ugly Truth). The US Congress and European Commission aren’t looking into their practices because they felt bored. It is because they capitalise on surveillance, hate and misinformation, all of which threaten the basic structures of democracy.

If Facebook (or Meta) claims they will prioritise security, interoperability and improving human relationships, as Zuckerberg did in interviews, such claims need scrutiny. Scrutiny from journalists, from software engineers, from activists and from trend watchers. This company has demonstrated on many occasions to be capable of mostly the opposite of security, the opposite of interoperability and the opposite of improving the quality of human relationships. What would Rohinga muslims or the White House staff think when they hear Zuckerberg say security matters to him? What about web developers who try to build interoperable web apps, only to find Facebook’s staff working on the React framework work around more than with web standards? What about the many societies that are driven apart by an effective machinery for medical and political misinformation? Will they feel their human to human relationships have improved?

As someone with family, friends and colleagues abroad, I have seen struggles with current digital spaces. They could improve by means of technology and better priorities. But should this be lead by the company whose technology and priorities worsened digital spaces so much?

And are more advanced digital environments the answer or does a better world already exist, as in, the real world? Mixing digital and real, as some Metaverse tech does, is super beneficial for corporations that see the web as a place to extract profit from. A Mixed Reality overlay adds not just fun or useful interactions, it adds another thing to measure. More data, for corporations like Facebook, means more profits.

Maybe I would be less sceptical if Zuckerberg had outlined in more detail how this would benefit the world first, or even demonstrate ways to guarantee the Metaverse won’t be just another layer of his data extraction machine. Of course, it is a free world and corporations can profit however they want. Including by building a data extraction machine and getting rich off that. Profit is fine, my company aims for profits too. It’s really Zuckerberg’s failure to address what could go wrong, given so much in his current enterprise has gone wrong, that tires me. It’s the combinaton of that data extraction machine for profit and the undesired impacts of it on society.

For a corporation wanting to extract data for profit, augmented reality is better than reality. For end users, reality itself, I mean, unaugmented reality, might be the better version of the mostly digitial lockdown life that many of us desire. First of all, it’s real, I mean, did you have a chance to experience life music after lockdowns? It’s nice, right? Secondly, it doesn’t require scary filming glasses or uncomfortable and nausea-inducing headsets. Thirdly, you have to worry less about whether your privacy is invaded. And if Facebook or Meta run things, you can be quite sure of that. I won’t be applying to one of the 50,000 ‘Metaverse jobs’ they said they’ll open in Europe.

Originally posted as The better version of digital life is real life, not ‘the metaverse’ on Hidde's blog.

With prefers-reduced-motion, developers can create UIs that don’t move when users opt out. Could this feature be a way of meeting WCAG 2.2.2 Pause, Stop, Hide?

Rian recently asked this question in Fronteers Slack and I thought I would write up some thoughts around this for later reference. I will go into three things: what’s 2.2.2 about, how could using prefers-reduced-motion be a way to meet it and is that desirable?

Moving, blinking and scrolling content can be a barrier to:

Success Criterion 2.2.2 says that for such content, there should be a “mechanism for the user to pause, stop, or hide it”. The exception is content that is considered “essential”, like when removing it would radically change the content or if this UI is really the only way to display the functionality. If this content auto-updates, a mechanism to set how often updates happen is also fine.

All of this is about content that moves regardless of user interaction. For content that moves when people “interact” (eg scroll or zoom), think parallax effects, this could badly effect people with vestibular disorders. 2.3.3 Animation from Interactions (Level AAA) is specifically about this interaction-triggered motion.

These days, most operating systems let users indicate whether they want to see less motion.

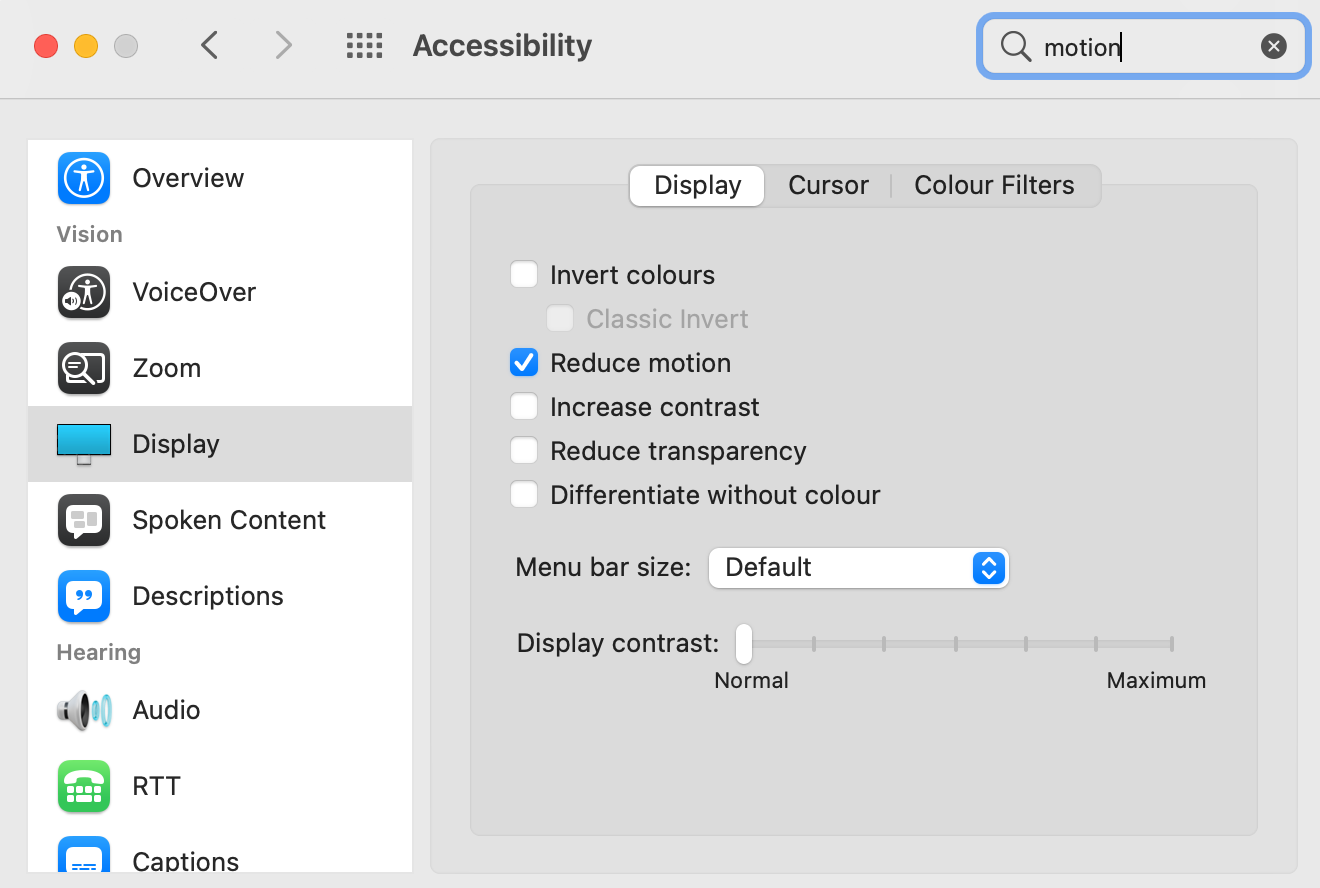

On macOS, the setting is under Accessibility, Display, Reduce motion

On macOS, the setting is under Accessibility, Display, Reduce motion

This functionality exists for pretty much the same reasons as Success Criterion 2.2.2. In Media Queries, Level 5, CSS adds a way for web developers to respond to and honour the setting to prefer reduced motion.

In CSS, it works like this:

.thing {

/* some rules */

}

@media (prefers-reduced-motion) {

.thing {

/* some rules for if user

prefers reduced motion*/

}

}In JavaScript, you can also read out the value for prefers-reduced-motion with matchMedia, and even add listen to its change event:

var query = window.matchMedia('(prefers-reduced-motion: reduce)');

query.addEventListener('change', () => {

if (!query.matches) {

/* some rules */

} else {

/* some rules for if user

prefers reduced motion*/

}

}I would say a UI that has moving parts that would cause it to fail 2.2.2, could meet it if those moving parts are removed under the condition of prefers-reduced-motion being set to true. In practice, for this to work, a user would have to set this preference in their operating system and they use a browser that supports it.

The crucial part of the Success Criterion text, I think, is:

for [moving, blinking and scrolling content] there is a mechanism for the user to pause, stop, or hide it

(emphasis mine; exception and exact definition of the content this applies removed for clarity)

I feel setting ‘prefers reduced motion’ could count as such a mechanism, for most cases of moving content.

In WCAG, there is this concept of ‘accessibility supported’, meaning that you can somewhat trust on platform features, but only if you’re certain they will work for most of your users. Like, if there was an amazing new HTML tag that allowed you to do very accessible tabs, but only one obscure browser can actually render it, that is not considered accessibility supported.

“Accessibility supported” requires two things to be true: it has to work in a user’s assistive technology and there are browsers, plugins or even paid user agents that support the feature (paid, as long as price and findability are same for users with and without disabilities). W3C and the WCAG authors (AGWG) only provide these rules, not a specification of what meets them or doesn’t meet them, so it’s up to the accessibility community to agree.

I believe this is a feature that doesn’t depend on assistive technology support as it lives in browsers, so I will deem that first clause to be not applicable and look just at the browser support. For ‘prefers-reduced-motion`, caniuse shows 93% of users are on browsers that support it. It is important to note that some screenreader users may be on older browsers, for a variety of reasons. Among respondents to WebAIM’s most recent screenreader user survey, Internet Explorer usage was 3.3%. To include even those users, one could use prefers-reduced-motion defensively.

I wrote this would be fine to meet WCAG in ‘most cases’. When is it not? Examples could be those when the ‘moving’ means the site adds new content, like in a stock ticker, as Jonathan Avila suggests on GitHub. Not adding that content would be undesirable, as it would make that content unavailable to users with the setting turned on.

If we want an accessible web, we shouldn’t just look for the bare minimum to conform. When I carry out accessibility conformance evaluations, measuring that minimum is what I consider my goal, but, of course, web accessibility is about more than such audits. People with disabilities should have equal usability and that requires best practices and user testing, in addition to standards conformance.

So, ‘is this desirable?’ is a usability question. Will people who need the setting actually discover, understand and use it? The setting can be in a variety of places. MDN has a list of settings that cause Firefox to honour prefers-reduced-motion, presumably these are similar for Chromium and Webkit based browsers. It seems likely to me that lots of people won’t find this setting. So it doesn’t just give control to end users, it also shifts the burden of knowing and using the setting to them. Operating systems can (and sometimes do) improve discoverability of features like these, though.

Generally, I love the idea of features like prefers-reduced-motion standardised primitives to accommodate specific user requirements. I think it’s better than every web developer inventing their own controls to meet the same user needs. In the case of 2.2.2, controls like pause buttons or duration settings. I love the idea that the platform offers generalised controls that aren’t just used on one specific website, but can be respected by all websites.

After I published this post, Bram Duvigneau of the Dutch accessibility consultancy Firm Ground, sent me a note that included a few more web platform features that help meet WCAG criteria:

The ‘Mute this tab’ button in a Firefox tab

The ‘Mute this tab’ button in a Firefox tab

The mute and text sizing buttons are much easier to find in web browsers for users. Should browsers also expose a much easier to find ‘stop motion’ button whenever a website implements prefers-reduced-motion, so that a user is more explicitly presented with this option?

As you can read, I’m a little torn on whether prefers-reduced-motion is a sufficient way to meet 2.2.2 Pause, Stop, Hide for specific cases of that criterion. In terms of conformance, I would say yes, this is acceptable (with exceptions). In terms of actual usability, which is what is most important, I’m torn as it only actually works if real users find this setting on their device.

Over to you! If you’re reading this, I would love to hear what you think!

Thanks to my friends in the Fronteers Slack #accessibility channel for discussing some of this together.

Update 6 December 2021: added “Similar features” section

With prefers-reduced-motion, developers can create UIs that don’t move when users opt out. Could this feature be a way of meeting WCAG 2.2.2 Pause, Stop, Hide?

Rian recently asked this question in Fronteers Slack and I thought I would write up some thoughts around this for later reference. I will go into three things: what’s 2.2.2 about, how could using prefers-reduced-motion be a way to meet it and is that desirable?

Moving, blinking and scrolling content can be a barrier to:

Success Criterion 2.2.2 says that for such content, there should be a “mechanism for the user to pause, stop, or hide it”. The exception is content that is considered “essential”, like when removing it would radically change the content or if this UI is really the only way to display the functionality. If this content auto-updates, a mechanism to set how often updates happen is also fine.

All of this is about content that moves regardless of user interaction. For content that moves when people “interact” (eg scroll or zoom), think parallax effects, this could badly effect people with vestibular disorders. 2.3.3 Animation from Interactions (Level AAA) is specifically about this interaction-triggered motion.

These days, most operating systems let users indicate whether they want to see less motion.

On macOS, the setting is under Accessibility, Display, Reduce motion

On macOS, the setting is under Accessibility, Display, Reduce motion

This functionality exists for pretty much the same reasons as Success Criterion 2.2.2. In Media Queries, Level 5, CSS adds a way for web developers to respond to and honour the setting to prefer reduced motion.

In CSS, it works like this:

.thing {

/* some rules */

}

@media (prefers-reduced-motion) {

.thing {

/* some rules for if user

prefers reduced motion*/

}

}In JavaScript, you can also read out the value for prefers-reduced-motion with matchMedia, and even add listen to its change event:

var query = window.matchMedia('(prefers-reduced-motion: reduce)');

query.addEventListener('change', () => {

if (!query.matches) {

/* some rules */

} else {

/* some rules for if user

prefers reduced motion*/

}

}I would say a UI that has moving parts that would cause it to fail 2.2.2, could meet it if those moving parts are removed under the condition of prefers-reduced-motion being set to true. In practice, for this to work, a user would have to set this preference in their operating system and they use a browser that supports it.

The crucial part of the Success Criterion text, I think, is:

for [moving, blinking and scrolling content] there is a mechanism for the user to pause, stop, or hide it

(emphasis mine; exception and exact definition of the content this applies removed for clarity)

I feel setting ‘prefers reduced motion’ could count as such a mechanism, for most cases of moving content.

In WCAG, there is this concept of ‘accessibility supported’, meaning that you can somewhat trust on platform features, but only if you’re certain they will work for most of your users. Like, if there was an amazing new HTML tag that allowed you to do very accessible tabs, but only one obscure browser can actually render it, that is not considered accessibility supported.

“Accessibility supported” requires two things to be true: it has to work in a user’s assistive technology and there are browsers, plugins or even paid user agents that support the feature (paid, as long as price and findability are same for users with and without disabilities). W3C and the WCAG authors (AGWG) only provide these rules, not a specification of what meets them or doesn’t meet them, so it’s up to the accessibility community to agree.

I believe this is a feature that doesn’t depend on assistive technology support as it lives in browsers, so I will deem that first clause to be not applicable and look just at the browser support. For ‘prefers-reduced-motion`, caniuse shows 93% of users are on browsers that support it. It is important to note that some screenreader users may be on older browsers, for a variety of reasons. Among respondents to WebAIM’s most recent screenreader user survey, Internet Explorer usage was 3.3%. To include even those users, one could use prefers-reduced-motion defensively.

I wrote this would be fine to meet WCAG in ‘most cases’. When is it not? Examples could be those when the ‘moving’ means the site adds new content, like in a stock ticker, as Jonathan Avila suggests on GitHub. Not adding that content would be undesirable, as it would make that content unavailable to users with the setting turned on.

If we want an accessible web, we shouldn’t just look for the bare minimum to conform. When I carry out accessibility conformance evaluations, measuring that minimum is what I consider my goal, but, of course, web accessibility is about more than such audits. People with disabilities should have equal usability and that requires best practices and user testing, in addition to standards conformance.

So, ‘is this desirable?’ is a usability question. Will people who need the setting actually discover, understand and use it? The setting can be in a variety of places. MDN has a list of settings that cause Firefox to honour prefers-reduced-motion, presumably these are similar for Chromium and Webkit based browsers. It seems likely to me that lots of people won’t find this setting. So it doesn’t just give control to end users, it also shifts the burden of knowing and using the setting to them. Operating systems can (and sometimes do) improve discoverability of features like these, though.

Generally, I love the idea of features like prefers-reduced-motion standardised primitives to accommodate specific user requirements. I think it’s better than every web developer inventing their own controls to meet the same user needs. In the case of 2.2.2, controls like pause buttons or duration settings. I love the idea that the platform offers generalised controls that aren’t just used on one specific website, but can be respected by all websites.

After I published this post, Bram Duvigneau of the Dutch accessibility consultancy Firm Ground, sent me a note that included a few more web platform features that help meet WCAG criteria:

The ‘Mute this tab’ button in a Firefox tab

The ‘Mute this tab’ button in a Firefox tab

The mute and text sizing buttons are much easier to find in web browsers for users. Should browsers also expose a much easier to find ‘stop motion’ button whenever a website implements prefers-reduced-motion, so that a user is more explicitly presented with this option?

As you can read, I’m a little torn on whether prefers-reduced-motion is a sufficient way to meet 2.2.2 Pause, Stop, Hide for specific cases of that criterion. In terms of conformance, I would say yes, this is acceptable (with exceptions). In terms of actual usability, which is what is most important, I’m torn as it only actually works if real users find this setting on their device.

Over to you! If you’re reading this, I would love to hear what you think!

Originally posted as Meeting “2.2.2 Pause, Stop, Hide” with prefers-reduced-motion on Hidde's blog.

The applause seemed louder than usual. They were stoked, this community of European nerds, designers and lots of people in between. At last. After almost two years without Beyond Tellerrand conferences, Marc Thiele decided to make it work and run another event. It was great to see him back on stage, introducing speakers and more.

Of course, it was anything but a normal event. Not all regulars could or wanted to attend. Naturally, they were missed. Those who did attend, mostly local or local-ish, had to stick to the ‘2G+’ rule: to be vaccinated, recovered or PCR tested. I felt lucky I could be there, to attend a number of wonderful talks, meet folks in person and speak. I didn’t find the risk assessment easy… for myself, for others… but, given the circumstances, it seemed like the right call to attend.

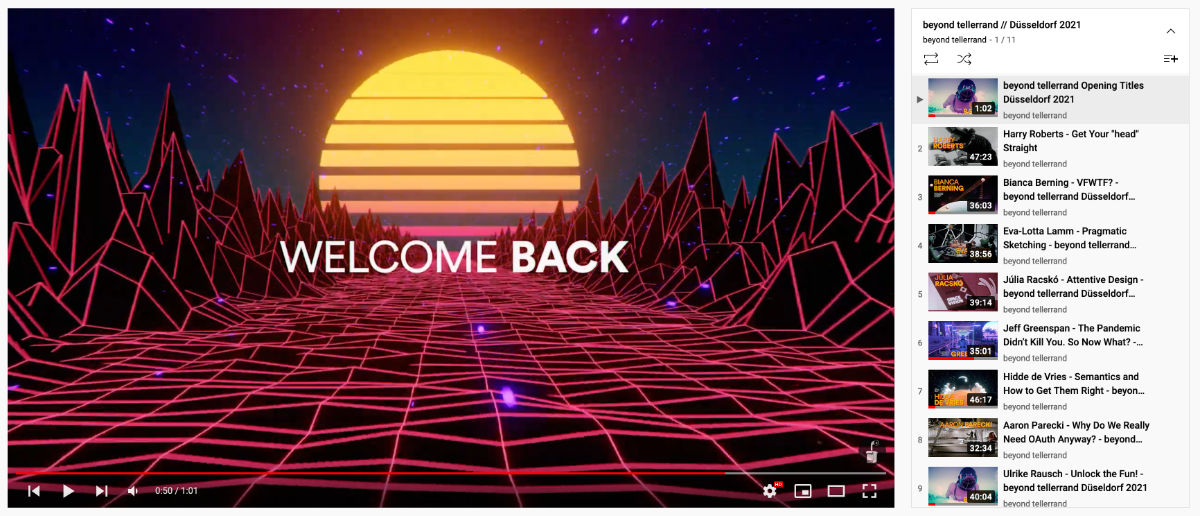

Recordings of last week’s Beyond Tellerrand are already up on YouTube and Vimeo. Check out the event page for links: there is awesome content about variable fonts, quarantine life, sketching as a tool, the <head> tag and how it affects web performance, the attention economy, OAuth from a usability perspective, creative typography and how modern font tech allows for it, data visualisation and experiencing disability.

Recordings for all talks are available

Recordings for all talks are available

I opened the second day with a full length talk just about semantics. Inspired by the Austrian-British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who equated meaning to use, I explained semantics is fundamentally about a system of meaning that is shared. Shared through a standard: HTML. This is how it differs from other examples of shared languages, like design systems and APIs. Through examples, I tried to show how semantic HTML affects end users and talked a little about gotchas (see the recording for more).

It was special to me to speak at Beyond Tellerrand. Not only was it ten years after attending the first edition, it was also after over a year of just virtual talks. Virtual events are great. They have allowed me to speak in more places, without the travel. Last month I could attend W3C TPAC and Accessibility Toronto on the same day, while I also met my manager in Boston for a 1:1 and cooked family dinner at home. Which brings me to the downside… if you can be everywhere at once, are you really anywhere fully?

In virtual events, I’ve often not attended the whole thing, because I find that a lot harder while at my desk and at home. At my desk, there is also other work waiting. At home, there is family. I love my work, but picking between work and family is easy, I will pick family, unless I’ve actually travelled away.

In person, it felt easier to focus on just the event. It meant that I could bump into people in the hallways. Not literally, of course. I got more immediate feedback and much more time with attendees, organisers and fellow speakers. The feeling of being in an auditorium with others, laughing about the same jokes, enjoying the same beautiful typography on a huge screen, inpromptu ramen lunches… it’s all hard to replicate virtually.

In the days after the conference, some of us gathered in the newly opened Zentralbibliothek, Düsseldorf’s public library. On Wednesday there was an Accessibility Club Meetup. I talked about opportunities for browsers to contribute to accessibility issues. Molly Watt shared her experiences as a deafblind user of technology and urged us to make less assumptions about and test more with users. Karl Groves warned us to not trust vendors of accessibility overlays. This was all livestreamed and it was awesome to watch Marc and Aaron setting up their elaborate streaming setup.

On Thursday, I left for home, but not before I had attended the informal yet important pre-event coffee session and the planning for that day’s Indie Web Camp. It was my first Indie Web Camp, and I had wanted to attend for a while. I decided to work on the Webmentions on this website. That afternoon, in my train back, I tweaked how likes and shares, the most common form of Webmention I receive here, are displayed. They now show all in one paragraph, rather than as individual comment-like entries. This cleaned up the comment section for most posts on this site, which was nice.

This was fun, and I hope it can happen again in the not too distant future. In the next few weeks, I have some more virtual and hybrid events. Here’s to hoping that 2022 will bring more opportunities to safely gather in person with web friends, including those who live further away. Because, for one, I missed this.

The applause seemed louder than usual. They were stoked, this community of European nerds, designers and lots of people in between. At last. After almost two years without Beyond Tellerrand conferences, Marc Thiele decided to make it work and run another event. It was great to see him back on stage, introducing speakers and more.

Of course, it was anything but a normal event. Not all regulars could or wanted to attend. Naturally, they were missed. Those who did attend, mostly local or local-ish, had to stick to the ‘2G+’ rule: to be vaccinated, recovered or PCR tested. I felt lucky I could be there, to attend a number of wonderful talks, meet folks in person and speak. I didn’t find the risk assessment easy… for myself, for others… but, given the circumstances, it seemed like the right call to attend.

Recordings of last week’s Beyond Tellerrand are already up on YouTube and Vimeo. Check out the event page for links: there is awesome content about variable fonts, quarantine life, sketching as a tool, the <head> tag and how it affects web performance, the attention economy, OAuth from a usability perspective, creative typography and how modern font tech allows for it, data visualisation and experiencing disability.

Recordings for all talks are available

Recordings for all talks are available

I opened the second day with a full length talk just about semantics. Inspired by the Austrian-British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who equated meaning to use, I explained semantics is fundamentally about a system of meaning that is shared. Shared through a standard: HTML. This is how it differs from other examples of shared languages, like design systems and APIs. Through examples, I tried to show how semantic HTML affects end users and talked a little about gotchas (see the recording for more).

It was special to me to speak at Beyond Tellerrand. Not only was it ten years after attending the first edition, it was also after over a year of just virtual talks. Virtual events are great. They have allowed me to speak in more places, without the travel. Last month I could attend W3C TPAC and Accessibility Toronto on the same day, while I also met my manager in Boston for a 1:1 and cooked family dinner at home. Which brings me to the downside… if you can be everywhere at once, are you really anywhere fully?

In virtual events, I’ve often not attended the whole thing, because I find that a lot harder while at my desk and at home. At my desk, there is also other work waiting. At home, there is family. I love my work, but picking between work and family is easy, I will pick family, unless I’ve actually travelled away.

In person, it felt easier to focus on just the event. It meant that I could bump into people in the hallways. Not literally, of course. I got more immediate feedback and much more time with attendees, organisers and fellow speakers. The feeling of being in an auditorium with others, laughing about the same jokes, enjoying the same beautiful typography on a huge screen, inpromptu ramen lunches… it’s all hard to replicate virtually.

In the days after the conference, some of us gathered in the newly opened Zentralbibliothek, Düsseldorf’s public library. On Wednesday there was an Accessibility Club Meetup. I talked about opportunities for browsers to contribute to accessibility issues. Molly Watt shared her experiences as a deafblind user of technology and urged us to make less assumptions about and test more with users. Karl Groves warned us to not trust vendors of accessibility overlays. This was all livestreamed and it was awesome to watch Marc and Aaron setting up their elaborate streaming setup.

On Thursday, I left for home, but not before I had attended the informal yet important pre-event coffee session and the planning for that day’s Indie Web Camp. It was my first Indie Web Camp, and I had wanted to attend for a while. I decided to work on the Webmentions on this website. That afternoon, in my train back, I tweaked how likes and shares, the most common form of Webmention I receive here, are displayed. They now show all in one paragraph, rather than as individual comment-like entries. This cleaned up the comment section for most posts on this site, which was nice.

This was fun, and I hope it can happen again in the not too distant future. In the next few weeks, I have some more virtual and hybrid events. Here’s to hoping that 2022 will bring more opportunities to safely gather in person with web friends, including those who live further away. Because, for one, I missed this.

Originally posted as In person on Hidde's blog.