Thanks Eric Bailey, Scott O’Hara, Eric Eggert, David Luhr and Erik Kroes for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of this post.

Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Boolean attributes in HTML and ARIA: what's the difference?

Some attributes in ARIA are boolean(-like). These attributes may seem a lot like boolean attributes in HTML, but there are some important differences to be aware of.

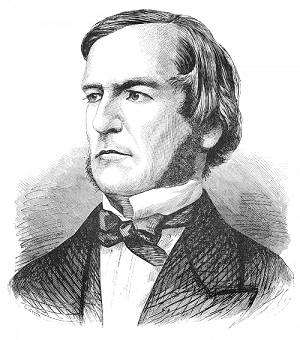

George Boole, the philosopher and mathematician who came up with a type of algebra that has just true and false as its variables

George Boole, the philosopher and mathematician who came up with a type of algebra that has just true and false as its variables

Boolean attributes in HTML

In HTML, some attributes are boolean attributes, which basically means they can be true or false. They are the case, or they are not the case. They compute to one, or they compute to zero. Examples of these attributes include checked, required, disabled and open.

Boolean attributes in HTML are true when they are present:

The presence of a boolean attribute on an element represents the

truevalue, and the absence of the attribute represents thefalsevalue.

(From: HTML, Common microsyntaxes, Boolean attributes)

So, if a checkbox is checked, it has the checked attribute, otherwise it does not. The attribute, when present, can have any value, like checked="checked", though the HTML spec explicitly says we should not use true or false as attribute values for boolean attributes:

The values “true” and “false” are not allowed on boolean attributes. To represent a false value, the attribute has to be omitted altogether.

It would work though: the checked attribute works with any value, even checked="true" or checked="false" represents that the input is checked:

<!--

on first render, the following

checkboxes are in checked state

-->

<input type="checkbox" checked="true" />

<input type="checkbox" checked="false" />

<input type="checkbox" checked="hello" />

<!--

on first render, the following

checkboxes are not in checked state

-->

<input type="checkbox" />In some cases, browsers will help us manage the presence of these attributes. They don’t for checked, but they do for details/summary (the open attribute on the details element when its summary is expanded or collapsed). In other cases, the browser can’t manage presence or absence, like for the required attribute. Whether an element is set to required, is up to the author’s intention, the browser defaults to “not required”.

The attributes I discussed earlier are what specifications call ‘content attributes’, we write them in our markup. In JavaScript, we can also affect the truth value of these HTML attributes with so-called IDL attributes, for instance:

element.checked = true; // sets checked state to true

element.checked = 'checked'; // sets checked state to true

element.checked = 'foo'; // also sets checked state to true

element.checked = false; // sets checked state to false

element.checked = ''; // sets checked state to falseBoolean attributes in ARIA

In ARIA, there are also attributes that can be true or false, but their state is expressed differently. It is a different language than HTML, after all. HTML is the most common host for it, but ARIA can also be used in other languages, like XML and SVG.

As explained previously, HTML has the concept of boolean attributes. It also has the concept of keyword and enumerated attributes. These attributes can come with a fixed number of string values. When ARIA is used in HTML, we use these types of attributes. This means that when we say “boolean” in ARIA, we’re really talking about strings that happen to be use the words “true” or “false”.

According to the type mapping table in the WAI-ARIA 1.1 specification, there are three different attribute types in ARIA that explictly list ”true” and “false” as possible values:

- attributes that are “boolean”, which accept only

"true"or"false"(egaria-busy,aria-multiline,aria-readonly) - attributes that accept

"true","false"and"undefined"(egaria-hidden,aria-expanded,aria-grabbed,aria-selected) - “tristate” attributes, which accept

”true”,"false"or"mixed"(egaria-checked,aria-pressed)

That’s not all, as there are also properties with different and larger sets of possible values:

aria-invalid(takes"grammar","spelling","false"and"true")aria-haspopup(takes"true","false","listbox","menu","tree","grid"and"dialog")aria-current(takes"true","false","page","step","location","date"and"time")

All of these fall into that “keyword and enumerated attributes” bracket, they take a nullable DOMString.

ARIA attributes can be set using setAttribute(). From ARIA 1.2, which is currently a “Candidate Recommendation Draft” (it’s like a Candidate Recommendation, but with significant updates made to it), ARIA attributes can be specified using IDL attributes, too, for instance:

element.ariaChecked = "true"; // sets `aria-checked` to trueScott O’Hara wrote about this upcoming feature in his post New in ARIA 1.2: ARIA IDL attributes.

HTML vs ARIA booleans

So, for HTML boolean attributes it’s all about presence and absence, while in ARIA boolean attributes, the boolean state is expressed via "true" and "false" string values and there are bunch of attributes that take those strings and a couple more.

Some examples of these differences:

- The absence of the

checkedboolean attribute maps toaria-checked="false"(unless it was modified, that is… so this mapping only applies in the elements default state) - The presence of the

disabledattribute maps toaria-disabled="true" - The presence of the

openattribute ondetailsmaps the state of itssummarytoaria-expanded="true", the absence of it maps it toaria-expanded="false"

Summary

So, there are boolean attributes and keyword and enumerated attributes in HTML. When ARIA booleans are used in HTML, they are of the latter type. They take one of two keywords: "true" or "false". There are also ARIA attributes that take "true" and "false", but also other keywords in addition. Those may look like booleans at first sight, but are not. That’s all, thanks for reading!

The post Boolean attributes in HTML and ARIA: what's the difference? was first posted on hiddedevries.nl blog | Reply via email

Use Firefox with a dark theme without triggering dark themes on websites

With prefers-color-scheme, web developers can provide styles specifically for dark or light mode. Recently, Firefox started to display dark mode specific styles to users who used a dark Firefox theme, even if they have their system set to light mode.

There is a flag in Firefox that determines whether dark/light preferences are taken from the browser or from the browser theme.

This is how you set it:

- Go to

about:config - Search

layout.css.prefers-color-scheme.content-override - Set it to

0to force dark mode,1to force light mode,2to set according to system’s colour setting or3to set according to browser theme colour

(via support.mozilla.org)

Personally, I feel respecting the system setting worked better. I hope it gets changed back. In the mean time, I hope this override helps.

Originally posted as Use Firefox with a dark theme without triggering dark themes on websites on Hidde's blog.

Boolean attributes in HTML and ARIA: what's the difference?

Some attributes in ARIA are boolean(-like). These attributes may seem a lot like boolean attributes in HTML, but there are some important differences to be aware of.

George Boole, the philosopher and mathematician who came up with a type of algebra that has just true and false as its variables

George Boole, the philosopher and mathematician who came up with a type of algebra that has just true and false as its variables

Boolean attributes in HTML

In HTML, some attributes are boolean attributes, which basically means they can be true or false. They are the case, or they are not the case. They compute to one, or they compute to zero. Examples of these attributes include checked, required, disabled and open.

Boolean attributes in HTML are true when they are present:

The presence of a boolean attribute on an element represents the

truevalue, and the absence of the attribute represents thefalsevalue.

(From: HTML, Common microsyntaxes, Boolean attributes)

So, if a checkbox is checked, it has the checked attribute, otherwise it does not. The attribute, when present, can have any value, like checked="checked", though the HTML spec explicitly says we should not use true or false as attribute values for boolean attributes:

The values “true” and “false” are not allowed on boolean attributes. To represent a false value, the attribute has to be omitted altogether.

It would work though: the checked attribute works with any value, even checked="true" or checked="false" represents that the input is checked:

<!--

on first render, the following

checkboxes are in checked state

-->

<input type="checkbox" checked="true" />

<input type="checkbox" checked="false" />

<input type="checkbox" checked="hello" />

<!--

on first render, the following

checkboxes are not in checked state

-->

<input type="checkbox" />In some cases, browsers will help us manage the presence of these attributes. They don’t for checked, but they do for details/summary (the open attribute on the details element when its summary is expanded or collapsed). In other cases, the browser can’t manage presence or absence, like for the required attribute. Whether an element is set to required, is up to the author’s intention, the browser defaults to “not required”.

The attributes I discussed earlier are what specifications call ‘content attributes’, we write them in our markup. In JavaScript, we can also affect the truth value of these HTML attributes with so-called IDL attributes, for instance:

element.checked = true; // sets checked state to true

element.checked = 'checked'; // sets checked state to true

element.checked = 'foo'; // also sets checked state to true

element.checked = false; // sets checked state to false

element.checked = ''; // sets checked state to falseBoolean attributes in ARIA

In ARIA, there are also attributes that can be true or false, but their state is expressed differently. It is a different language than HTML, after all. HTML is the most common host for it, but ARIA can also be used in other languages, like XML and SVG.

As explained previously, HTML has the concept of boolean attributes. It also has the concept of keyword and enumerated attributes. These attributes can come with a fixed number of string values. When ARIA is used in HTML, we use these types of attributes. This means that when we say “boolean” in ARIA, we’re really talking about strings that happen to be use the words “true” or “false”.

According to the type mapping table in the WAI-ARIA 1.1 specification, there are three different attribute types in ARIA that explictly list ”true” and “false” as possible values:

- attributes that are “boolean”, which accept only

"true"or"false"(egaria-busy,aria-multiline,aria-readonly) - attributes that accept

"true","false"and"undefined"(egaria-hidden,aria-expanded,aria-grabbed,aria-selected) - “tristate” attributes, which accept

”true”,"false"or"mixed"(egaria-checked,aria-pressed)

That’s not all, as there are also properties with different and larger sets of possible values:

aria-invalid(takes"grammar","spelling","false"and"true")aria-haspopup(takes"true","false","listbox","menu","tree","grid"and"dialog")aria-current(takes"true","false","page","step","location","date"and"time")

All of these fall into that “keyword and enumerated attributes” bracket, they take a nullable DOMString.

ARIA attributes can be set using setAttribute(). From ARIA 1.2, which is currently a “Candidate Recommendation Draft” (it’s like a Candidate Recommendation, but with significant updates made to it), ARIA attributes can be specified using IDL attributes, too, for instance:

element.ariaChecked = "true"; // sets `aria-checked` to trueScott O’Hara wrote about this upcoming feature in his post New in ARIA 1.2: ARIA IDL attributes.

HTML vs ARIA booleans

So, for HTML boolean attributes it’s all about presence and absence, while in ARIA boolean attributes, the boolean state is expressed via "true" and "false" string values and there are bunch of attributes that take those strings and a couple more.

Some examples of these differences:

- The absence of the

checkedboolean attribute maps toaria-checked="false"(unless it was modified, that is… so this mapping only applies in the elements default state) - The presence of the

disabledattribute maps toaria-disabled="true" - The presence of the

openattribute ondetailsmaps the state of itssummarytoaria-expanded="true", the absence of it maps it toaria-expanded="false"

Summary

So, there are boolean attributes and keyword and enumerated attributes in HTML. When ARIA booleans are used in HTML, they are of the latter type. They take one of two keywords: "true" or "false". There are also ARIA attributes that take "true" and "false", but also other keywords in addition. Those may look like booleans at first sight, but are not. That’s all, thanks for reading!

Originally posted as Boolean attributes in HTML and ARIA: what's the difference? on Hidde's blog.

Boolean attributes in HTML and ARIA: what's the difference?

Some attributes in ARIA are boolean(-like). These attributes may seem a lot like boolean attributes in HTML, but there are some important differences to be aware of.

George Boole, the philosopher and mathematician who came up with a type of algebra that has just true and false as its variables

George Boole, the philosopher and mathematician who came up with a type of algebra that has just true and false as its variables

Boolean attributes in HTML

In HTML, some attributes are boolean attributes, which basically means they can be true or false. They’ll be the case, or not the case. Some examples: checked, required, disabled and open.

Boolean attributes in HTML are true when they are present:

The presence of a boolean attribute on an element represents the

truevalue, and the absence of the attribute represents thefalsevalue.

(From: HTML, Common microsyntaxes, Boolean attributes)

So, if a checkbox is checked, it has the checked attribute, otherwise it does not. The attribute, when present, can have any value, like checked="checked", though the HTML spec explicitly says we should not use true or false as attribute values for boolean attributes:

The values “true” and “false” are not allowed on boolean attributes. To represent a false value, the attribute has to be omitted altogether.

It would work though: the checked attribute works with any value, even checked="true" or checked="false" represents that the input is checked:

<!--

on first render, the following

checkboxes are in checked state

-->

<input type="checkbox" checked="true" />

<input type="checkbox" checked="false" />

<input type="checkbox" checked="hello" />

<!--

on first render, the following

checkboxes are not in checked state

-->

<input type="checkbox" />In some cases, browsers will help us manage the presence of these attributes. They don’t for checked, but they do for details/summary (the open attribute on the details element when its summary is expanded or collapsed). In other cases, the browser can’t manage presence or absence, like for the required attribute. Whether an element is set to required, is up to the author’s intention, there are no browser defaults.

The attributes I discussed earlier are what specifications call ‘content attributes’, we write them in our markup. In JavaScript, we can also affect the truth value of these HTML attributes with so-called IDL attributes, for instance:

element.checked = true; // sets checked state to true

element.checked = 'checked'; // sets checked state to true

element.checked = 'foo'; // also sets checked state to true

element.checked = false; // sets checked state to false

element.checked = ''; // sets checked state to falseBoolean attributes in ARIA

In ARIA, there are also attributes that can be true or false, but their state is expressed differently. It is a different language than HTML, after all. HTML is the most common host for it, but ARIA can also be used in other languages, like XML and SVG.

As explained previously, HTML has the concept of boolean attributes. It also has the concept of keyword and enumerated attributes. These attributes can come with a fixed number of string values. When ARIA is used in HTML, we use these types of attributes. This means that when we say “boolean” in ARIA, we’re realling talking about strings that happen to be use the words “true” or “false”.

According to the type mapping table in the WAI-ARIA 1.1 specification, there are three different attribute types in ARIA that explictly list ”true” and “false” as possible values:

- attributes that are “boolean”, which accept only

"true"or"false"(egaria-busyandaria-multiline,aria-readonly) - attributes that accept

"true","false"and"undefined"(egaria-expanded,aria-grabbed,aria-selected) - “tristate” attributes, which accept

”true”,"false"or"mixed"(egaria-checked,aria-pressed)

That’s not all, as there are also properties with different and larger sets of possible values:

aria-invalid(takes"grammar","spelling","false"and"true")aria-haspopup(takes"true","false","listbox","menu","tree","grid"and"dialog")aria-current(takes"true","false","page","step","location","date"and"time")

All of these fall into that “keyword and enumerated attributes” bracket.

ARIA attributes can be set using setAttribute(). From ARIA 1.2, which is currently a “Candidate Recommendation Draft” (it’s like a Candidate Recommendation, but with significant updates made to it), ARIA attributes can be specified using IDL attributes, too, for instance:

element.ariaChecked = "true"; // sets `aria-checked` to trueScott O’Hara wrote about this in more detail about this upcoming feature in his recent post New in ARIA 1.2: ARIA IDL attributes.

HTML vs ARIA booleans

So, for HTML boolean attributes it’s all about presence and absence, while in ARIA boolean attributes, the boolean state is expressed via "true" and "false" string values and there are bunch of attributes that take those strings and a couple more.

Some examples of these differences:

- The absence of the

checkedboolean attribute maps toaria-checked="false"(unless it was modified, that is… so this mapping only applies in the elements default state) - The presence of the

disabledattribute maps toaria-disabled="true" - The presence of the

openattribute ondetailsmaps the state of itssummarytoaria-expanded="true", the absence of it maps it toaria-expanded="false"

Summary

So, there’s boolean attributes and keyword and enumerated attributes in HTML. Booleans in ARIA are of the latter type, so they work slightly differently than boolean attributes in HTML and take a number of keywords, sometimes many more than true and false, at which point they aren’t really booleans.

Thanks Eric Bailey, Scott O’Hara, Eric Eggert and Erik Kroes for feedback on an earlier versions of this post.

The post Boolean attributes in HTML and ARIA: what's the difference? was first posted on hiddedevries.nl blog | Reply via email

Joining Sanity

Mid February I will start a new job: I am excited to join the developer relations team at Sanity!

I had my last day at W3C in October (look, my cool URI didn’t change) and set out to be mostly away from work for a couple of months. I guess I’m not great at this, as, besides another school lockdown here, I got fairly busy with existing projects. I did some WCAG audits, workshops, conference talks and… interviewing. I wanted to make sure to find the right place and took the time to do it. Having been a contractor for over a decade, it was my first time doing interviews, eh, ever.

My work at WAI taught me to consider the web in terms of systems like authoring/developer tools and user agents, as they impact the web in some very specific ways. It became clear to me I wanted my next role to be at a company that is heavily involved in somehow making the web better through tools like that. Whatever a better web looks like… more accessible, more secure, more privacy-aware… I got to talk to a number of different companies working on browsers, design system tooling, browser add-ons, web standards and content management tools. I could write about the job hunting process, but Mu-An already did that brilliantly.

The Sanity developer relations team made a great impression. The company has a cool product that solves some important problems, a friendly community (plus focus on keeping it healthy), lots of ecosystem, aaaand… there could be lots of new ecosystem possibilities. Sanity’s Year in 2021 blog post has a lot more detail on what Sanity is up to.

For the next few weeks, I will be finishing my current accessibility consulting projects with the Dutch government and Mozilla, go on holiday and then, get this new chapter started!

The post Joining Sanity was first posted on hiddedevries.nl blog | Reply via email