Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

“That's not accessible!” and other statements about accessibility

“We're 100% accessible”, some digital products claim. “That solution is inaccessible”, an accessibility specialist might say. These sorts of statements almost suggest that web accessiblity is a binary thing. Is it though?

In this post, I'll talk about why it's most helpful to see a website's accessibility as a continuum (or, you know, multiple continua). Even then, in some contexts, it makes sense to pretend it is binary.

If you find this interesting, but want actionable advice, see also Adrian Roselli's post Things to Do Before Asking “Is This Accessible?”

It is a spectrum

The accessibility of a website is a spectrum, in terms of different disabilities that exist, in terms of timing and in terms of objective claims.

The goal of web accessibility is that people with disabilities can use the web. In other words, it is about people and maximising the portion of people who can use our UI well. There are people who can't move their arms, who use their screen zoomed in, whose vision is blurry, who control their computer with their voice, and so forth. Accessibility is about people with a wide range of disabilities, that sometimes overlap, too. Our UI could be accessible to most or all of these people, or to some, or to none. Most products are accessible to at least some people with disabilities. Many have specific barriers for users from specific groups. Some do really well at continuously identifying barriers and removing them. Some don't.

Second, it is about timing: today all podcasts on our site may be transcribed, tomorrow we may upload an episode without a transcript. Or launch a new campaign that was done by this agency that didn't take all accessibility requirements into account. It happens. Accessibility can't be solved once and then shipped, it's a continuous process of tracking potential barriers and removing them. “That site is accessible” is a statement that changes over time on websites where content changes.

Third, accessibility conformance testing is subjective to some extent. This isn't a bug in accessibility standards, it's more like a most reasonable choice… If we tried hard, we could invent success criteria that can be evaluated with 100% certainty, but then we would need many of them, they might go out of date fast and they might end up a lot less technology agnostic. The subjectivity serves a purpose, but it's there, and again, a reason that a claim like “this is accessible” is hard to make.

So, basically, there is a degree of subjectivity in determining whether something is accessible, because it matters to which user(s), when it is checked and what is checked. For that reason, a statement like “this is accessible” or “this is not accessible” is best taken with a pinch of salt.

Why pretend it's not

A claim of “great accessibility” is subjective, a bit like “great user experience” and “great design”. Especially when you view “meeting WCAG” as a minimum and aim much higher by doing regular user testing and following best practices beyond WCAG (see my other post about using a superset of WCAG). But sometimes it makes sense to try and make formal and objective-like claims about the accessibility of a website or set of websites. To publish reports that say things like “60% of webshops in Germany are inaccessible” or “Only 10% of online banking is accessible”. Those are usually based on automated tests and/or accessibility conformance reports that refer to standards like WCAG.

One example of when it makes sense to pretend accessibility is objective, is the effectiveness of policy. National governments and organisations like the European Commission want to have a more accessible web, they have this as a policy goal. For that to be more than dreams or empty statements, they need to make it practical and tangible. Their method of measuring success is, roughly speaking, to gather accessibility statements and conformance reports. On the one hand, this reduces the experiences of people with disabilities to checking boxes in a standard, on the other hand, this provides insights at scale, while maintaining a reasonably good representation of individual experiences.

WCAG is used as a way to make statements about websites. Combined with a method like WCAG-EM, a detailed process for evaluating conformance published by the W3C, governments can get some level of certainty.

As an example, The Dutch government has a register of over 3500 accessibility conformance statements. They are each about a specific website, to which a rating between A (“fully meets WCAG”) and D (“does not meet WCAG”) is assigned. Rating E means “statement is missing”. Other efforts include AllAble's accessibility statements research, looking at accessibility statements from public sector bodies in the United Kingdom.

Of course, this approach is not perfect. Individual organisations might be using an auditing agency that is biased or not very good at evaluating WCAG. Some might self-evaluate (generally not a good idea). Or a website could have serious accessibility issues that happen to not be captured by WCAG (it happens). But even with some of those caveats in mind, even if the data is not 100% objective (is data ever?), collecting information from a large set of websites is the best a government can do. Regular formal WCAG/ATAG audits is a great thing for companies and organisations to do too, though ideally that strategy is supplemented by regular user tests and review of best practices.

Wrapping up

In summary: yes, measuring web accessibility is somewhat subjective and claims like “X is accessible” or “X is inaccessible” are tricky. If someone makes such statements, grab a pinch of salt! But, having said that, it can be helpful to talk about accessibility as “meets the criteria in this standard” and “does not meet the criteria in this standard”. Governments do this to measure the success of their policies and companies can do it to have some measurement of their own success. That's mostly useful, even though user tests and best practices based on them are even more meaningful.

Originally posted as “That's not accessible!” and other statements about accessibility on Hidde's blog.

How I built a dark mode toggle

This site has had dark and light modes for a while, but it never offered any choice. If your system preference was “dark”, that's what you would get (unless you used fancy browser flags). Yesterday, I implemented a dark mode toggle, so that you can override that at your leisure. In this post I will talk about some of the choices I made along the way. Basically, it's a long winded way of saying why it took me so long.

This is fun to fiddle around with, but really, it seems to me that all websites have this requirement, so why isn't this built into browsers? In other words, I agree with Bramus Van Damme, dark mode toggles should be a browser feature. His post has more reasons: however you support light and dark modes, you will likely end up with code duplication somewhere, and toggles that live in developer land require JavaScript.

The choices

HTML

There are a lot of HTML elements that you can use to give users a choice between one out of many options. Radio buttons and <select>s come to mind. A checbox could be an option too… if there is only one option, checkboxes too allow just the one option.

I started out with radio buttons as I thought that was clever, and even ended up building the control all the way from coding a form a fieldset, legend and options. I went ahead to visually hide the control itself and then use the :checked pseudo class to only display the option that wasn't picked. In other words, when dark mode was on, the light mode option was visible and vice versa.

It's a whole form!

It's a whole form!

It must have been late, because only when I started testing this with keyboard, a sanity check I do with all controls, I realised it didn't feel right. With a keyboard, you would need arrow keys to pick the other option and that feels weird, especially for a control that is styled to not look like radio buttons. I guess the lesson is: never style elements too far from their original purpose.

I ended up going for just the one button element. To switch styles, I would need JavaScript either way, so I would not benefit from having a checkbox in this case. In Underengineered Toggles Too, Adrian Roselli explains that the button makes sense if the control only works with JavaScript (check; we need to toggle a class or attribute to apply the CSS), if it only has true or false states, not mixed (check; we allow either light or dark) and if flipping the control immediately performs an action (check; the color scheme changes straightaway). The great thing about a button element, just for the record, is that it comes with keyboard support built-in. No extra cost.

It's a button!

It's a button!

One button, like mine, does mean that users can't explicitly choose that they want my site to follow their browser or OS setting. In his post Your dark mode toggle is broken, Kilian Valkhof makes the case for including a “system” setting that would solve this very problem.

CSS

With CSS, I made the button look like not a button. I visually hid the text inside of it. I also added an SVG icon that I applied pointer-events: none to, so that clicks on the SVG would be registered as clicks on the button.

JavaScript

In script, I wanted a couple of cases to be covered. Let's walk through the various parts of the implementation.

First, I stored the button and the query to find out if a dark color scheme is preffered, and created an empty variable for the current theme:

var button = document.querySelector('.theme-selector');

var prefersDark = window.matchMedia('(prefers-color-scheme: dark)');

var currentTheme;I also added a function to set a theme, which adds an attribute to the html element and stores the preference in localStorage:

function setTheme(currentTheme) {

var pressed = currentTheme === 'dark' ? 'true' : 'false';

document.documentElement.setAttribute('data-theme-preference', currentTheme);

localStorage.setItem('theme-preference', currentTheme);

}Then I figured out what the theme should be. First I checked if there is something in localStorage, if not if there is a preference for dark mode, and if not, I set it to default to light mode:

if (localStorage.getItem('theme-preference')) {

currentTheme = localStorage.getItem('theme-preference');

} else if (prefersDark.matches) {

currentTheme = 'dark';

} else {

// default

currentTheme = 'light';

}We also want ways to change the theme. First off, when the user clicks the button:

button.addEventListener('click', function(event) {

currentTheme = document.documentElement.getAttribute('data-theme-preference') === "dark" ? "light" : "dark";

setTheme(currentTheme);

});Secondly, when the user changes their theme preference:

prefersDark.addEventListener('change', function(event) {

currentTheme = event.matches ? 'dark' : 'light';

setTheme(currentTheme);

});(This listens to changes in the browser's MediaQueryList, which could change when the setting is changed in the browser or the OS).

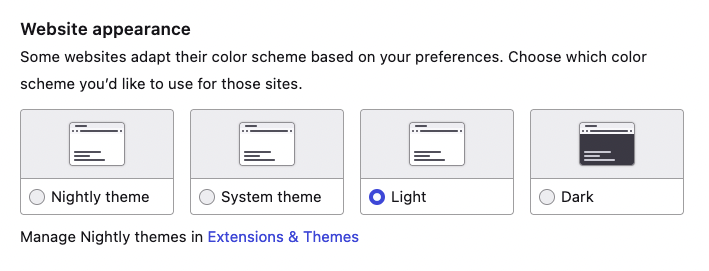

In Firefox, you can pick light or dark mode, if you don't want it to just follow the system or your choice of Firefox theme. There is no per website setting at the time of writing.

In Firefox, you can pick light or dark mode, if you don't want it to just follow the system or your choice of Firefox theme. There is no per website setting at the time of writing.

ARIA

In my book, it's ideal to only use ARIA when it is for something that:

- doesn't exist in HTML

- brings a known benefit to end users

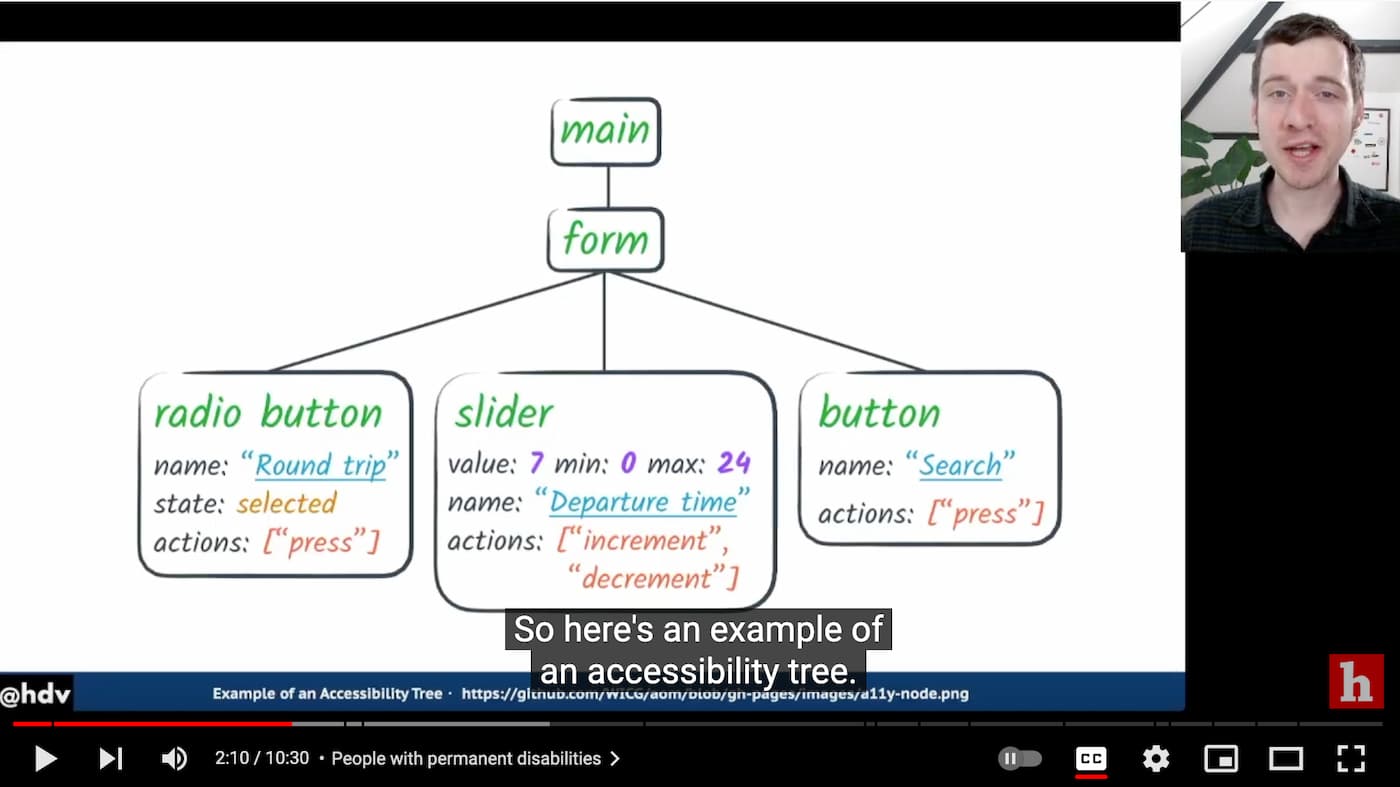

In this case, we're using a standard button element, which exists in HTML. But there is one detail about it that doesn't exist in HTML, which is that this is the type of button that toggles. We can add this by setting the aria-pressed with a "true" or "false" value.

This brings a known benefit to end users, specifically to users of screenreaders, who will now hear this is a toggle button. For toggle buttons, it is important that the content doesn't change. As the button text, I have used “Toggle dark mode”.

If we would update the label of the button from “Turn on light” to “Turn on dark”, we kind of have a toggle (as MDN suggests), but that way, it wouldn't be recognised by the browser and set in the accessibility tree to be a toggle, and, because of that, not announced as a toggle by screenreaders.

Compromises

Code duplication

In his post, Bramus explains that when you want to build a dark mode toggle, you will end up with duplicated CSS. That is, if you both want to see color changes support the prefers-color-mode media query, and the class or attribute that you're toggling with your toggle. I went for not supporting that media query directly in CSS. Instead, I rely on my script to set the right data attribute. This means that without JavaScript, users will only see the light mode, even if their system or browser setting is to use dark mode.

Honouring the system preference

As mentioned above, my toggle doesn't have a “do whatever the system does” setting. However, when you change the system setting, it will notice and use that system setting. That is, until you change your preference again, either via the toggle or the system setting.

Many themes

The toggle I ended up with can only swap between two states. Initially I had wanted it to work for any number of states, I mean, why not have lots of different themes between light and dark? It's tricky, because how do those two settings, that the media query currently supports checks for, map to my many themes? This may be something for future iterations, probably with some way to map two specific themes to be the browser's “light” and ”dark”.

Summing up

To build a dark mode toggle is an exercise full of compromises. There are many ways that, proverbially, lead to Rome, as you can read above. I was happy enough with the current result to ship it for now, but am more than open to feedback.

Originally posted as How I built a dark mode toggle on Hidde's blog.

ATAG: the standard for accessibility of content creation

ATAG is a set of guidelines for the accessibility of authoring tools. In this post I'll talk about what it is and why it matters.

Most people working on websites will be familiar with WCAG, the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. There are two more related standards, one for user agents (like browsers) and one for authoring tools (like CMSes, WYSIWYG or Markdown editors, e-learning platforms and website creators). They work together: if we care about the accessibility of web content, we should also care about how it is created (in authoring tools) and displayed (in user agents).

“Web content” in accessibility standards refers to websites, apps and other content on the web. I like to think of it as the HTML that browsers serve to the user when they access your website or app. There isn't a definition for “web content” in WCAG, but there is one for “web content technologies”. From that definition we can draw that web content includes anything that is rendered by user agents, like HTML and SVGs.

Why ATAG matters

Better accessibility of content tools is critical for three reasons:

- Everyone should be able to create content for the web, regardless of disability.

- Authoring tools are in between the user and the HTML they create.

- The authoring tool can have the unique ability to prevent inaccessibility.

Let's look at these reasons in a little more detail.

Content creation is for everyone

‘The web is for everyone’, as web inventor Tim Berners-Lee likes to say, applies as much to accessing websites as it does to creating them. His first browser had both viewing and editing capabilities, so clearly the web was always meant to be about both consumption and creation. Many of us love to create vlogs, set up online classes, publish recipes, tweet, make TikToks, create art… this should just work for people with or without disabilities. If content creation tools have barriers, that's everyone's loss.

The first web browser, “WorldWideWeb”, was also an editor.

The first web browser, “WorldWideWeb”, was also an editor.

In business, it would be illogical (and illegal) if you couldn't hire content professionals with disabilities, just because they can't use your content tools. In your company today, Harry from marketing might be able to use a mouse, but when he leaves his successor might only use keyboards.

Support for all of HTML

The second part to authoring tool accessibility is their ability to output accessible content. Imagine two tools to create bulleted lists. One does this with divs and images of bullets, the other uses the standard ul and li elements. The latter is what we need, and not just when dealing with lists, but for all kinds of markup:

tableswithcaptionsvideoswithtrackelements andmutedandautoplayattributesfieldsets withlegends- images with

altattributes - translated content with

langattributes

Not all tools let you create all or these structures, at which point they basically become the accessibility issue.

Authoring tools as accessibility assistants

Even cooler than outputting sensible and appropriate markup, authoring tools could provide hints. They could try to be a helpful “accessibility assistant”, by point our potential barriers when they notice you're creating them. For instance, if an authoring tool lets you pick a foreground and background colour, it could warn you when you pick two colours that have insufficient contrast.

ATAG recommends various ways of assisting with making content more accessible: accessible default components and templates, solid documentation and, as described above, suggestions and hints.

Who meets ATAG

At the time I am writing this, I am not aware of any authoring tools that meet 100% of ATAG, as in, all criteria at level A or AA. That doesn't mean all is lost, every bit helps and there are a lot of authoring tools that meet many bits of the standard.

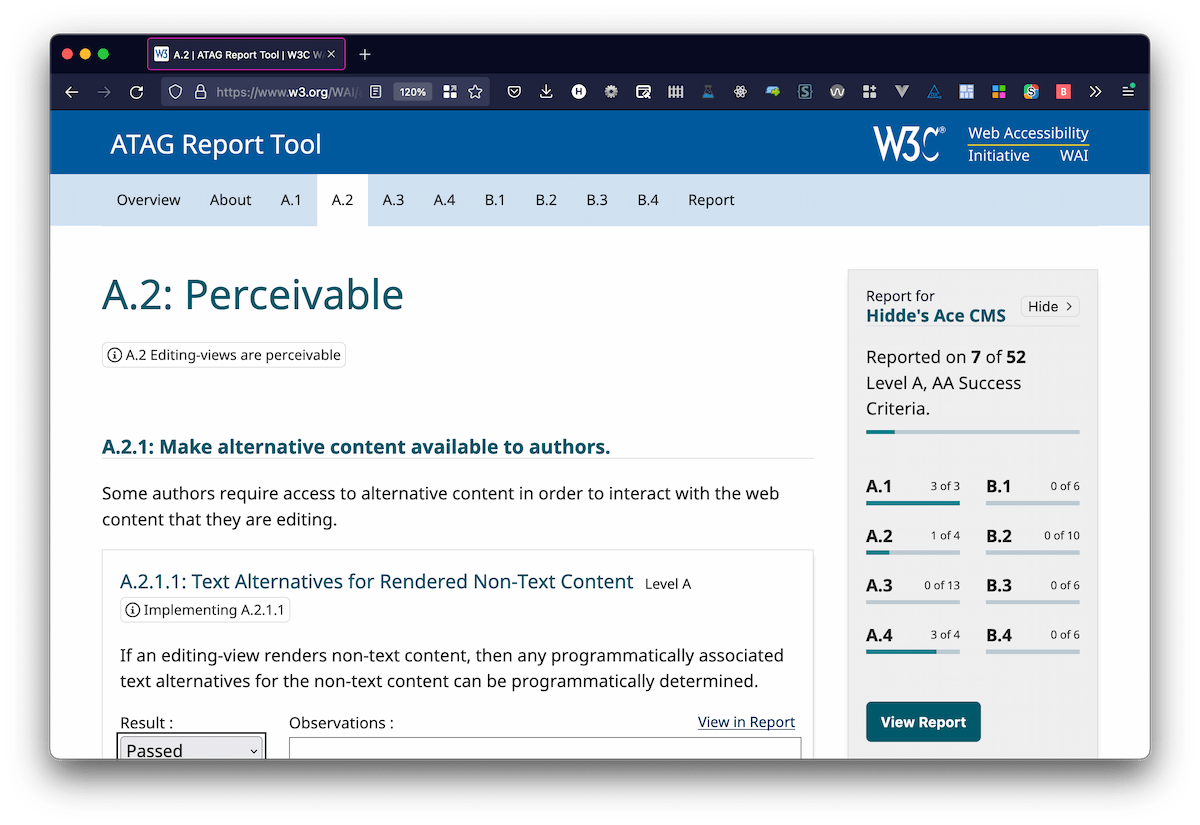

With the ATAG Report Tool, people can create a report with specific details about which parts of ATAG they do or do not meet.

As described above, there are lots of good reasons to try and meet ATAG. It is a worthwhile pursuit for authoring tool makers and a worthwhile request for procuring departments to put in tenders.

What's in ATAG

There are two parts to the ATAG standard:

- editing experience (part A): does the tool work for people with disabilities?

- output (part B): does the tool output accessible content?

If you're still with me, I'd like to describe ATAG in a bit more detail. Like WCAG, ATAG has Principles, Guidelines and Success Criteria. In the following sections, I will discuss the Principles and Guidelines in my own words. Full and official wording is in the ATAG 2.0, published by the W3C. This is not legal advice.

Authoring tool UI meets accessibility guidelines

- Web-based functionality is accessible:

The full editing experience conforms to WCAG 2.0 or other accessibility guidelines. (A.1.1) - Non-web-based functionality is accessible:

The interface conforms to platform-specific accessibility guidelines. (This one specifically applies to authoring tools that are not web-based, which was more common when ATAG came out) (A.1.2)

Editing UI is perceivable

- Alternative content available to editors:

If there is anything visible that is not text, like icons, images or video, there is alternative text available. (A.2.1) - What's indicated visually in the UI can be programmatically determined:

Status indicators (like changes or spelling errors) and text properties (like italics or bold) are conveyed to users of assistive technologies. (A.2.2)

Editing UI operable

- Works with keyboard:

Everything that can be done with a mouse, can just as easily be done with a keyboard, including drag and drop and drawing capabilities. There should be no keyboard traps. Keyboard usage should be efficient and easier to use than just with sequential access (for example: use WAI-ARIA landmarks or offer keyboard shortcuts). (A.3.1) - Enough time:

Time limits in the editor, like for auto-save, can be turned off or extended (some exceptions apply). (A.3.2) - Flashing content optional:

Flashing content, like videos, including previews of that kind of content, can be paused or turned off. (A.3.3) - Content can be navigated by structure:

Users can navigate quicker by structure, for example headings, lists or HTML elements. (A.3.4) - Content searchable:

Users can search in text content, results are focused when shown. If there are no matches, this is indicated. User can search in two directions (backwards and forwards). (A.3.5) - Supports display preferences:

If there are user settings for display, this only affects the editing view, not the output. If a content editor uses OS settings like high contrast mode or their own stylesheet, this does not break the editing experience. (A.3.6) - Previews are accessible:

When the tool shows a preview of the content, that preview is at least as accessible as in current browsers and other user agents. (A.3.7)

Editing UI is understandable

- Helps editor prevent and correct mistakes:

The tool lets users undo changes and settings. (A.4.1) - (Accessibility) features documented:

The tool has documentation for all features, including accessibility features. (A.4.2)

Fully automatic processes produce accessible content

- Generates accessible markup:

When the tool generates markup, that markup is accessible. If accesssibility information is required, like alternative texts, the content editor is prompted to provide that information. (B.1.1) - Preserves accessibility information:

If content is pasted from a word processor or converted from one format into another, any accessibility information is preserved. (B.1.2)

Supports producing accessible content

- Accessible content production is possible:

If some options produce more accessible content than others, they are displayed more prominently. If properties and attributes can be set, those relevant for accessibility can also be set. (B.2.1) - Editors guided:

Editors are guided to produce accessible content. (B.2.2) - Text alternatives can be managed:

There is a tool for providing text alternatives to “non-text content”, like images, videos and data visualisation. (B.2.3) - Accessible templates available:

There are accessible templates available. If there is a repository of templates, it is easy to find the ones that prioritise accessibility. (B.2.4) - Accessible components/plug-ins available:

If any components or plugins are built-in to the tool, they are accessible. If there is a gallery of components or plug-ins, it indicates accessible options. (B.2.5)

Helps with improving the accessibility of existing content

- Checks accessibility automatically:

Has built-in checks for common accessibility problems, for example a check to identify missing alternative text. (B.3.1) - Helps content editors fix problems:

Provides suggestions to content editor about accessibility problems. (B.3.2)

Promotes and integrates accessibility features

- Accessibility features prominent:

Accessibility features are on by default and a prominent part of the editing workflow. Documentation shows examples of how to create accessible content, for instance with example markup or screenshots. (B.4.1) - Documentation promotes accessibility:

The tool provides suggestions to content editors about accessibility problems. (B.4.2)

Wrapping up

In summary, ATAG recommends two things:

- a fully accessible authoring tool interface (basically, one that meets WCAG)

- the possibility to produce accessible “web content” and help with that in the form of documentation, default templates and suggestions

The instructions are more detailed in the standard, but that's what it comes down to in most cases.

Though the standard is only met at most partially by most tools today, a wider landscape of ATAG-supporting tools would be fantastic for web accessibility (because it's easier when you do it earlier). Increasingly, authoring tool makers start to realise this and that is wonderful.

Originally posted as ATAG: the standard for accessibility of content creation on Hidde's blog.

Accessibility from different perspectives

I worked in web accessibility in different setups: as a freelance developer specialised in accessibility, as a WCAG auditor and as a full time team member of the W3C's Web Accessibility Initiative. As a developer I would receive audit reports, as an auditor I would write them and as a WAI team member I would work on promoting and documenting the standards these audits are based on. An observation: in the developer role, advocating for accessibility can be the hardest in various ways.

Perspectives

Writing audit reports, a company would request in-depth feedback with the intent to fix stuff (ideally; sometimes it's just because the law says they have to 🤷). At WAI, I engaged with accessibility standards and practices on more of a meta level. When developing tools or resources, I never had to explain why I wanted videos to be captioned or have a visible focus indicator on the stuff we published, because everyone else on the team had worked with WCAG for years, often decades, and many had lived experienced to draw from.

In the developer role, I had more responsibilities than ensuring accessibility, I also had to make sure our assets didn't break under an updated Content-Security-Policy, fix a deployment pipeline or figure out with which templating language my client could use their design system most widely. And then there was accessibility, my main interest and priority. I mean, why have a web app if it's inaccessible… I would often do that work under the radar, sometimes because other developers in the team weren't interested or skilled in that particular area, sometimes because I felt it would take more time to get extra time for a thing than to just do the thing.

Accessibility and support

Accessibility is hard to do bottom up, I found. In some cases, especially when working for government and non profits, accessibility would explicitly be in the requirements and or I would specifically be hired for that expertise. This was great and gave something to work with. In other situations, it was much more of a challenge. Time would go into making a business case (I learned about WAI's business case page late), trying to get budget for external audits or screenreader licenses (procuring JAWS is no fun) and figuring out how to go about recruiting users with disabilities for user tests. And that's still the meta stuff.

When it comes to writing code as an accessibility specialised developer, you can ensure you follow lots of users with disabilities and accessibility specialists to try and learn about implementation issues early. You can find lots of good resources. My favourite are blog posts by developers and accessibility specialists who have tested a solution with users and go at length to describe all the ifs and buts you need to understand the nuance and compromise. But let's be honest, if you want to rely on the official documentation (normative or not) that is also used by browsers and assistive technologies, it can be pretty difficult to find out exactly what to do.

Gaps in documentation

There are systematic problems in accessibility standards documentation:

- outdated examples are often not marked as outdated and hardly ever removed

- it is not always clear if examples are ready to use or merely displays of how stuff ‘should work’ if all browsers and assistive technologies followed the standards (a problem ARIA Authoring Practices Guide has)

- it's hard to find user-tested examples

- the guidance can be scattered across many places

From the standards org perspective this is all explainable. There is a lot of work on few plates, the consensus process and organisational structure have, besides benefits, an impact on how responsibilities can be and are distributed. It's understandable, but has an effect. It impacts how effectively developers (and designers, content editors etc) can build accessible products. Even if from the standards side of things, you can only do so much to try and have standards that are implemented interoperably by browsers and assistive technology makers. There are relatively few people in the space who specialise in this.

Channeling one's inner developer

From the auditor's perspective, as well as from the standards org perspective, accessibility looks different. The system is, sadly, ableist and almost every website you look at has accessibility conformance and usability issues… it has often frustrated me and made me more cynical than I want to be. You write down the same issues over and over, knowing they are just a few lines of code. I always had to channel my inner developer again, and remember what it can be like. Yes, removing the line outline: none is trivial, and it's extremely ableist to keep it in, but what can a developer do if the QA and/or design departments flag it as a bug and they're the only one on the team who ‘gets’ this need. Let's not blame the developer, let's blame the ableist system we all operate in. Or, as Adrian Roselli recently said, ‘arm developers’ with useful feedback so that they are more enpowered to make the changes (being an auditor often puts one in this somewhat rewarding position).

I don't know where I'm going with this, but thinking about what I'd like to see for the web if I had a magic wand, I would want to see better accessibility documentation (clear, up to date and user tested), more engineering budget for compatibility between standards, browsers and assistive technologies and have legal requirements that make it so that serious organisations see accessibility like they see security and data protection. At least some if not all of these wishes are in progress, of course, in various places… they have been for years, I just wish ✨ change ✨ could be sooner.

Developer experience and user experience

Some say ‘user experience is more important than developer experience’, and I'm all for that sentiment. Of course. Web accessibility is all about users with disabilities. That's the point of it. Developers ‘just’ need to do the job.

But companies who make products they want developers to use effectively, like browsers, have dedicated developer experience teams to try and ensure that developers can use their stuff well. To try and set them up for success. In their case, that makes good business. Might we, as the accessibility field, also benefit from better developer experience (of web accessibility) to get to more widely spread user experience?

What if standards orgs hired content designers, like governments with similarly complex content do so successfully? Isn't explaining standards essential when making standards? In the majority of cases, an inaccessible pattern can be addressed in code, by developers. Might some focus on developer experience be a sensible means to an end? If it was less frustrating to find out how to build, say, a combobox, in practice not in theory, we would more easily get to the end goal: less frustrating experiences to end users.

Besides a focus on quality of documentation, I feel like we should keep the individual developer's perspective in mind, acknowledging they may have constraints beyond their control. We could contribute to fight those constraints by providing executives and team leads with the right tools too. We've got to set teams up for success. That way we all win.

Originally posted as Accessibility from different perspectives on Hidde's blog.

More common accessibility issues that you can fix today

Last month, I wrote about fixing common accessibility issues. That post seems to have resonated with people, so I have written up five more fixes you could do to your codebase today. Let's go!

I have tried to make these as hands-on as possible. For each, you'll find a description of what the issue problem, how fixing it helps end users and which team member can take the lead on it.

In my last post, the issues were what WebAIM described as the top 5 isuses in their WebAIM Million project. This time, I have looked into accessibility audit reports I wrote and combined that with what Deque wrote about coverage and the numbers that 200OK took from public data about common issues across the Dutch government websites (taken from the register of accessibility statements).

Missing focus states

If an element on a page is focusable, it needs a focus state. This goes for all interactive elements:

a(if the href attribute is present),audio(if the controls attribute is present),button,details,embed,iframe,img(if theusemapattribute is present),input(if thetypeattribute is not in the Hidden state),label,select,textarea,video(if the controls attribute is present)

(from: HTML, Interactive content)

It also goes for as well for divs or other elements that have click and keyboard events (but best use buttons in those cases while you're at it; see below).

For all of these, designers can come up with a focused state (ideally this is one thing, eg an outline, that is the same for all elements on the site, so that it's easy to spot when focus moves). Developers can remove any outline: nones from their stylesheets (if you must undo default outlines, because you're using some other CSS property for outlines, best use outline-color: transparent instead so that it doesn't break in High Contrast Mode).

Browsers can also ship with a feature that forces focus indication, some do. Users could also use user styles, though no website owner should expect they will, it requires CSS knowledge and a plugin in most browsers these days.

More: Indicating focus to improve accessibility

Missing captions and transcriptions

When you publish how-to videos, vlogs, podcasts, basically anything that has audio and/or video, the content should be available as text, too.

My friend Darice de Cuba has written about how to create podcasts transcripts. Part of this applies to video, too. Captions and transcripts are created for end users with disabilities. They also benefit users who are learning your language and users who want to catch your content but are in public without headphones. Transcripts and captions can even benefit your SEO strategy.

One of my own videos with captions turned on (It's the markup that matters on YouTube)

One of my own videos with captions turned on (It's the markup that matters on YouTube)

Writing out all recorded content isn't necessarily something you could do today as it can take a bit of time, especially if you have lots of content. I still felt I could include this common issue here, because most teams don't do this themselves and outsource the work to specialised agencies. These are costs you can budget for. If there is too much current content, you could consider starting with future or most popular content?

Project managers can make sure captioning and transcribing are part of any project that includes audio or video. Developers can ensure the CMS has fields for transcripts and captions. Designers can design the UI to allow for full transcript display. Social media managers can produce caption any videos for LinkedIn or Twitter.

Invalid HTML

There used to be a time when websites would proudly display a badge that showed the current page was composed of valid HTML. These badges have disappeared from most websites, but validation is still a sound accessibility strategy.

The HTML of web pages is parsed by lots of tools, like browsers and assistive technologies, if the HTML is invalid it can lead to unexpected bugs. Simon Pieters' Idiosyncrasies of the HTML parser is a great book about this, especially if you want a deep dive into what could possibly go wrong.

Since HTML5, error handling is specified as part of HTML, which should improve unexpected bugs due to invalid HTML, but there are still plenty of accessibility problems you can find by validating your HTML. Did you accidentally nest a <button> inside of a <a>? The validator will call it out and help you prevent the myriad of problems that could cause.

So… developers and test automation engineers can ensure HTML validation is included in tests.

More: validator.nu that allows inputting HTML by URL, file upload or pasting is (can run from command line per instructions in README)

Headings that don't describe their section

In HTML, headings (h1-h6 elements) exist in the context of a section, they are supposed to describe the content that follows them. When I say section, I don't mean specifically content in a <section> (or other “sectioning content”), I mean more generically content that forms a logical part of a page, regardless of which HTML element used.

Descriptive headings are useful, because some users access headings in a page as a table of contents. For example, your one page band website could have a “Discography”, “Tickets” and “Merchandise” headings. Your search application could have a filters section with a “Filters” heading. Some websites useheading tags (h1-h6) to mark up text that's “just” bigger or bolder, which will break the experience for people who navigate by headings, as it will add entries into their navigation that don't describe sections.

Content designers can ensure headings describe sections, and that things that don't describe sections aren't marked up as headings. developers can ensure that if there are headings in their front-end components, that they describe content and don't just exist for style reasons.

Can't do all things with just a keyboard

Accordions, tabs, ‘toggletip’ triggers… if your page or app has things that users can click on, they should also be usable with just a keyboard.

Fixing this issue is great for people who can only use a keyboard, and for users with numerous other devices that may or may not be keyboard like (there's some examples in How people with disabilities use the web).

Often, this issue occurs when clickable elements are divs with a click handler. Developers can make sure they use a button element whenever things can be clicked (or a if it navigates to somewhere). Yes, you need some CSS to change the styling to your liking, but this is do-able, it makes it easier for you to get all of the web platform's buttonness in one package and, most importantly, your users will thank you.

Wrapping up

So, that's five more common accessibility issue that you could fix in your codebase today. I hope this is helpful to some readers. Should you still have questions about any of these, please feel free to contact me on Twitter (@hdv) or via email.

Originally posted as More common accessibility issues that you can fix today on Hidde's blog.