Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Responsive day out 3: the final breakpoint

Yesterday I attended the third (and hopefully not final) edition of Responsive Day Out, Clearleft’s one day conference about all things responsive web design.

The talks were very varied this year. There were practical talks about improvements to the web with features like Web Components, Service Workers and flexbox. There were also conceptual talks, which looked at meta issues surrounding responsive web design: how web designers and developers adopt new ways of working or choose not to do so, and how to work together.

Like last year, the conference was hosted by Jeremy Keith, talks were divided into four segments, with three short talks in each segment, followed by a short interview-like discussion.

Jeremy Keith opening Responsive Day Out 3

Jeremy Keith opening Responsive Day Out 3

Part 1: Alice Bartlett, Rachel Shillcock and Alla Kholmatova

In the first segment, Alice Bartlett looked at whether and how we might be able to come up with a business case for accessibility, Rachel Shillcock looked at the relationship between web design and accessibility and Alla Kholmatova did a fantastic talk about (libraries of) patterns and, amongst other things, how to name them.

The business case for accessibility

Coming up with a business case may be a much shorter route to getting everyone on board with accessibility

Alice Bartlett from the Government Digital Service opened with a convincing talk about how to sell accessibility. Designing and building websites accessibly is a no-brainer to web designers and web developers who are convinced by the moral case for accessibility. But to some, that argument won’t cut it. There may be people in your organisation that want to learn more about the return on investment, and instead of trying to make the moral case, coming up with a business case may be ‘a much shorter route’ to getting everyone on board with accessibility, Alice said.

A business case is a document that proves that you have a problem and shows how you can solve it in the most cost effective manner. For accessibility this is hard, as there is not much evidence to show that accessibility solves the problems that we assume it solves. Sites that are accessible may be more maintainable, better for SEO or beneficial to usability, but, said Alice, there is hardly any evidence supporting such claims. See also Karl Groves’ series of blog posts about this, and the conclusion of that series.

Litigation may prove to be a way out: if non-accessibility is something one can be sued for, accessibility may be the result of a strategy avoiding being sued. The problem with that approach, is that whereas the risk of being sued is likely to be substantial for high profile companies, it is unlikely to be big enough to make a case for low profile companies. This should not stop us from making low profile companies’ sites accessible, but it does show that coming up with a business case for accessibility is problematic.

Accessibility and web design

Rachel Shillcock is a web designer and talked about how she integrates accessibility in her web design workflow. She gave practical tips and discussed tools like Lea Verou’s Contrast Ratio for determining WCAG colour compliance, HTML Code Sniffer that checks your front-end code for potential problems in web accessibility guidelines compliance, and tota11y, a similar tool that was recently launched by Khan Academy. Rachel made the moral case for accessibility: she emphasised that accessibility is a responsibility and that improving it can hugely improve your users’ lives.

Pattern libraries and shared language

Alla Kholmatova talked about the pattern library she works on at Future Learn. One of the problems she highlighted, is the boundary between a component being just something on its own, and it having enough similarities to something else to form a shared component. Like in language, interpretations may vary. I may see two separate components, you may see one component and one variation. “Naming is hard”, Alla explained. Visual names like ‘pink button’ are easy, but will quickly become limiting and burdensome (to the project). Functional names may be better, but then you might end up with two components that have different functions, but are visually the same. Higher level functions could be the basis for better names.

Alla emphasised that language is incredibly important here, shared language in particular. Pattern libraries and frameworks for modular design like atomic design and material design are ‘examples of controlled vocabularies’, she said. Naming is the method teams use to establish such frameworks. The framework will be used by the team, therefore the naming should be done by the team that will use it. The language that is established should remain in use to stay ‘alive’ and keep its meaning. Because a name like ‘billboard’, one of Alla’s examples, is quite broad. By using it in daily conversations, it remains meaningful. It made me think of Wittgenstein, who held that language only has meaning in virtue of the group / community it is used in.

Many of their naming conversations […] are done with everyone involved: not just designers or developers, but also content producers and users.

She explained how the team at Future Learn work on their shared language: they have a wall with all the (printed out) bits of design of their website for reference and overview. Many of their naming conversation takes place on Slack, and are done with everyone involved: not just designers or developers, but also content producers and users. They look at terminology of architecture and printing press for inspiration.

Part 2: Peter Gasston, Jason Grigsby and Heydon Pickering

In the second part, Peter Gasston talked about the state of web components, Jason Grigsby explained some of the puzzles of responsive images and Heydon Pickering showed how when viewing CSS as (DOM) pattern matches, clever CSS systems can be built.

Web Components

Peter Gasston gave an overview of Web Components, which provides a way for web developers to create widgets or modular components, that can have their own styles and behaviour (as in: not inherited from the page, but really their own). React and BEM have provided ways to do that with existing tech, Web Components brings it to the browsers.

There are four key modules to Web Components: templates, HTML imports, custom elements and Shadow DOM.

- Templates offer a way to declare reusable bits of markup in a

element. Works everywhere but IE. - HTML imports lets you import bits of HTML. Major problem: these imports block rendering (the imported file can link to stylesheets or scripts, which will need to be fetched). This may be replaced altogether by ES6 Modules.

- Custom elements let you have meaningful markup with custom properties. You create them in JS. The custom element names have a hyphen in them, because standard HTML elements will never have those, so browsers know which ones are custom. ES6 also offers a way to do this, possibly better, ES6 Classes.

- Shadow DOM: hide complex markup inside an element. This works by creating a shadow root (

createShadowRoot()). Little agreement amongst browser vendors about other features than thecreateShadowRootfunction. Still a lot to be defined.

Custom elements in Web Components bring a lot of responsibility, as they are empty in terms of accessibility, SEO and usability. With standard HTML elements, browsers have those things built in. With custom elements, they become the developer’s responsibility, Peter stressed. Potentially, there will be a lot of badly built Web Components once people start playing with them (like there are a lot of badly built jQuery plug-ins). The Gold Standard Peter mentioned may be a helpful checklist for how to build a Web Component and do it well. Peter also said we should use the UNIX philosophy: ‘every component does one job [and does it really well]’.

Peter said Web Components are good enough to be used now (but not for a business to depend on). He recommended using a library like Polymer for those who want to explore Web Components in more detail.

Responsive images

Jason Grigsby discussed Responsive Images, which has now shipped in most browsers and will work in others (IE and Safari) soon. His talk was about the why of responsive images. It has been designed to serve two use cases: resolution switching (best quality image for each resolution) and art direction (different image in different circumstances).

One of the puzzles around responsive images, Jason explained, is when to add image breakpoints. What dictates when to add an image breakpoint? Art direction might dictate breakpoints; this can be figured out and is mostly a design/art direction concern. Resolution might also dictate breakpoints, but this is much harder to figure out. How do we figure out how many breakpoints to use? In many companies, three breakpoints would to mind (phone-tablet-desktop), but that’s pretty artificial.

The ideal image width is the width it will have as it is displayed on the page. But in many responsive websites, images are sized with a percentage and can have many, many different widths, so often, some bytes will be ‘wasted’. So the question is: what is a sensible jump in file size? Maybe we should use performance budgets to make our choices about image resolutions? Important to note here, is that the larger the image, the larger the potential number of bytes wasted. That means we should have more breakpoints at larger sizes, as at larger sizes, differences are more expensive in bytes.

We can distinguish between methods that tell the browser exactly which image to use when, and methods that let the browser choose what is best. In most cases, Jason recommended, the latter is probably best: we just let the browser figure out which image to use.

Solving problems with CSS selectors

Heydon Pickering looked at making use of some powerful features of CSS (slides). He disagrees with those that say CSS is badly designed and should be recreated in JavaScript (‘pointless’) and showed in his talk how we can use the very design of CSS to our own benefit. CSS is indeed very well designed.

Most grid systems are not grid systems, they are grid prescriptions

Most grid systems out there, Heydon argued, aren’t much of a system. As they are not self-governing, they are more like grid prescriptions. Automatic systems can be done, using the power of CSS. Heydon suggested to look at CSS selectors as pattern matches. Matching containers full of content, we can look at how many bits of content we have, and let the browser come up with the best grid to display our content in. In other words: quantity queries. With nth-child selectors, Heydon showed how we can create a ‘divisibility grid’: looking at what your total amount of columns is divisible by, we can set column widths accordingly.

BEM-like conventions create order and control, but they throw out the baby with the bathwater by not using the cascade. The divisibility grid and quantity queries that Heydon create chaos, one might say, but as he rightly pointed out, this is in fact a ‘controllable chaos’.

Part 3: Jake Archibald, Ruth John and Zoe Mickley Gillenwater

The third segment started off with Jake Archibald, who talked about progressive enhancement in ‘apps’, followed by Ruth John who discussed a number of so-called Web APIs and lastly Zoe Mickley Gillenwater, with a talk about the many uses of flexbox on Booking.com.

Offline first

“A splash screen is an admission of failure”

Jake Archibald looked at progressive enhancement on the web, and showed how progressive enhancement and web apps are a false dichotomy. He emphasised it is indeed a great feature of the web that web pages show content as soon as they can, as opposed to last decade’s native apps, that often show a loading screen until everything you will ever need has loaded. On the web, we don’t need loading screens, yet some web apps have mimicked this behaviour. Jake argued this is a mistake and we can do better: ‘a splash screen is an admission of failure’. On the web, we can actually have users play level 1, even when the rest of the game is still loading in the background.

Jake Archibald making the case for progressive enhancement

Jake Archibald making the case for progressive enhancement

Some web app slowness exists because all the required JavaScript is requested as one big lump, with a relatively big file size. Not a huge problem in ideal, fast WiFi situations, but quite a PITA for those with two bars of 3G on the go. Or for those accessing the web on what Jake referred to as Lie-Fi.

People may say all the JavaScript should download first, as it is a ‘web app’, and that this is how ‘web apps’ work, but that will not impress users. We can actually load the essential bits of JavaScript first and others later. Although this will decrease total loading time, it can hugely increase the time to first interaction. This is more important than overall load time: people will likely want to use your thing as soon as possible.

>A Service Worker can be put in place to make sure users can always access the cached version first, even when offline

After the first load, assets can be stored in cache. A Service Worker can be put in place to make sure users can always access the cached version first, even when offline. Whilst the cached version is being displayed, everything else else can be taken care of in the background, you can notify the user when it is ready. I felt this is a bit like offering your restaurant guests a table and some bread and wine, whilst you prepare their starter. You don’t have to let them stand outside until everything is ready, that would get them unnecessarily annoyed.

Service Workers, that allow for taking over the network management of the browser and thus for serving cache/offline first, can be used now. Not because they have support across all browsers ever made, but because they are pretty much an extra layer on top of your existing application. If your browser doesn’t understand this mechanism to get the app served from cache first, that’s okay, it will just be served a fresh version (as it would have been without a Service Worker). If it does, you can save your users from Lie-Fi.

Link: SVG OMG (load it, turn WiFi off, load it again, it still works!)

Web APIs

Ruth John talked us through various different Web APIs, or as she likes to call them: client side web APIs. She showed interesting demoes of Geolocation, which gives access to a user’s location if they give permission, including a ‘watch’ function that can update so that you could build a sat nav application, Web Animation, which offers the animation properties from CSS in JavaScript, the Web Audio API, that lets one manipulate audio amongst other things, and finally the Ambient Light API, that gives us the tools to do useful little improvements for our users.

Flexbox

Zoe Mickley Gillenwater works at hotel booking website Booking.com, which is a hugely flexible website, as it is served in many different languages and on many different screen sizes and browsers.

When designing for the web, Zoe explained, we can used fixed units like px, or relative units, like rem or vw. Relative units can be a useful ‘best guess’, let you be close to an ideal, and work in many different circumstances. Even better than flexible units, is designing without units at all. Flexbox allows you to do exactly this. It lets you tell the browser an element’s starting size and whether it can grow/shrink, and lets the browser figure out the math.

[Flexbox] does responsive lay-outs without media queries

Flexbox, Zoe showed, is great for improving whitespace and wrapping for better coherency in lay-out. It often does this better than floats, inline-block or table-cell, but can (and probably should) be used in conjunction with those, as they provide a usable feedback. It is also great for reordering: with its ‘order’ property, you can achieve visual improvements by setting an element to display in another place than your source order. Lastly, it does responsive lay-outs without media queries, as it will display within your constraints and figure out its ‘breakpoints’ all by itself.

Zoe pointed out that the interesting difference between flexbox and other CSS features, is not really code, but our way of thinking about lay-out. It requires a bit of a mental shift. Responsiveness, Zoe concluded, is not binary, it is a continuum, and flexbox can help making your site more responsive. You can make lots of small minor changes to your site, each of which can make it more flexible. Browsers will make use of those improvements if they understand them, devices will make use of them if they are smaller or bigger than usual (most of them are, but all in different ways).

Part 4: Rosie Campbell, Lyza Gardner and Aaron Gustafson

In the final part, Rosie Campbell looked at the future of web design beyond the screens as we know them, Lyza Gardner pleaded for generalists in the web industry and Aaron Gustafson presented his idea of what we should expect next.

Beyond the screen

Rosie Campbell from the BBC talked us through some of the experiments she was involved with at the BBC Research lab. She noted that screens will only get weirder, and urged us to think about designing for such screens that don’t even exist yet. How? Stay agnostic to underlying hardware, she recommended. And reconsider assumptions: we are used to designing with rectangles, but future screens may be round, or indeed have completely different sizes. We should not be afraid of constraints, but embrace them as they can fuel creativity.

Skillsets

Lyza Gardner talked about how the web designer/developer job has changed in recent years, and what that does to us as people that just try to work in the web industry.

The web used to be much simpler, Lyza explained. In the beginning there was no JavaScript, there were no stylesheets, even images hardly had browser support. These constraints made working on the web interesting. This has changed hugely, as we now have a daily influx of new frameworks, tools and methodologies to learn about, consider adopting and perhaps specialise in. Because there is now so much information about so many different things we can do with the web, working on the web has become quite complex. There is more than anyone can possibly keep up with. This, Lyza said, can make us feel down and unsure.

[Generalists] think and talk about the web with nuance

The web industry celebrates specialists, we adore single subject rock stars, but we should be careful not to dismiss people that don’t specialise, but generalise. Generalists, unlike specialists, cannot show off their specialisms on their CV, and may not be great at fizzbuzz, but they have other things to offer. They can think and talk about the web with nuance. They synthesise and when combining synthesis with their skills, show how valuable they are. When given a problem they have not seen before, they can synthesise and do it. Generalists are beginners over and over again.

We should be generalists, Lyza concluded, we should cultivate wisdom and share it.

Where do we go from here?

The day was concluded by Aaron Gustafson, who looked at what’s next. The A List Apart article Responsive web design, Aaron said, was the first to provide a concrete example of the principles of A Dao of Web Design (speaking of how valuable generalists are…). That article goes into the flexible nature of information on the web. Content created once, accessible anywhere, as it was envisioned by Tim Berners-Lee.

Accessibility is core to the web, and it goes hand in hand with the flexible approach John Allsopp and Ethan Marcotte describe in their articles.

Accessibility is core to the web, and it goes hand in hand with the flexible approach John Allsopp and Ethan Marcotte describe in their articles. Don’t make assumptions about how people want to access your website, just let them access it in any way they want, by providing solid mark-up of well structured content.

Accessible websites have a benefit in the future of the web. There will be more controls and inputs, like gaze and eye/facial tracking. Voice will play a bigger role, too. You may have provided CSS with your content to display it beautifully across devices, but those users using voice will not see that. They will just be listening, so it is of utmost importance that your mark-up is well structured and the source order makes sense. That it is accessible.

Responsive web design, Aaron concluded, is all about accessibility. It is about making things accessible in the best possible way.

Wrap-up

As may have become clear from my notes above, Responsive Day Out 3 was a day full of variety. I had the feeling it could have easily been called Web Day Out, and I guess that makes sense, as responsive web design has naturally grown to be a pleonasm in the past few years.

I found a couple of common themes throughout the talks:

- Let the browser figure it out. Throw multiple image types/resolutions at it, and let the browser decide which one to display, as Jason explained. Or like Zoe demonstrated, tell the browser roughly how you want your element to be with flexbox, and let the browser figure out the maths. Give it some relatively simple CSS instructions, and let it grid your content for you, as Heydon did.

- Soon, we will be given more responsibilities. As Peter noted, Web Components will let us define our own components, which makes us responsible for setting up their usability and accessibility. Service Workers, as Jake showed, put us in control of network handling, so that we can decide how to handle requests (and respond to them with offline/cached content first). If we use Web Components or Service Workers, we explicitly choose not to let the browser figure it out, and provide our own algorithms.

- Responsive web design is all about accessibility. Although it is hard to make a business case for it, accessibility is very important, as it is a core concept of the web, as Aaron mentioned, and, being mostly device-agnostic, our best bet at future proofing content for screens that don’t even exist yet, as Rosie pointed out.

- Make things as flexible as you can. Good responsive design makes things very flexible. Flexbox and the non-binary improvements it creates, as Zoe discussed, make sure things work in many places at the same time.

Originally posted as Responsive day out 3: the final breakpoint on Hidde's blog.

The accessibility tree

At this month’s Accessible Bristol, Léonie Watson talked about improving accessibility by making use of WAI-ARIA in HTML, JavaScript, SVG and Web Components.

The talk started with the distinction between the DOM tree, which I assume all front-end developers will have heard of, and the accessibility tree. Of the accessibility tree, I had a vague idea intuitively, but, to be honest, I did not know it literally exists.

The accessibility tree and the DOM tree are parallel structures. Roughly speaking the accessibility tree is a subset of the DOM tree.

— W3C on tree types

The accessibility tree contains ‘accessibility objects’, which are based on DOM elements. But, and this is the important bit, only on those DOM elements that expose something. Properties, relationships or features are examples of things that DOM elements can expose. Some elements expose something by default, like <button>s, others, like <span> , don’t.

Every time you add HTML to a page, think ‘what does this expose to the accessibility tree?’

This could perhaps lead us to a new approach to building accessible web pages: every time you add HTML to a page, think ‘what does this expose to the accessibility tree?’.

Exposing properties, relationships, features and states to the accessibility tree

An example:

<label for="foo">Label</label>

<input type="checkbox" id="foo" />In this example, various things are being exposed: the property that ‘Label’ is a label, the relationship that it is a label for the checkbox foo, the feature of checkability and the state of the checkbox (checked or unchecked). All this info is added into the accessibility tree.

Exposing to the accessibility tree benefits your users, and it comes for free with the above HTML elements. It is simply built-in to most browsers, and as a developer, there is no need to add anything else to it.

Non-exposure and how to fix it

There are other elements, like and <div> that are considered neutral in meaning, i.e. they don’t expose anything. With CSS and JavaScript, it is possible to explain what they do, by adding styling and behaviour.

<!-- this is not a good idea -->

<span class="button">I look like a button</span>With CSS and JavaScript, it can be made to look and behave like a button (and many front-end frameworks do). But these looks and behaviours can only be accessed by some of your users. It does not expose nearly enough. As it is still a <span> element, browsers will assume its meaning is neutral, and nothing is exposed to the accessibility tree.

Léonie explained that this can be fixed by complementing our non-exposing mark-up manually, using role and other ARIA attributes, and the tabindex attribute.

<!-- not great, but at least it exposes to the accessibility tree -->

<span class="button" role="button">I am a bit more button</span>For more examples of which ARIA attributes exist and how they can be used, I must refer you to elsewhere on the internet — a lot has been written about the subject.

Exposing from SVG

With SVG becoming more and more popular for all kinds of uses, it is good to know that ARIA can be used in SVG. SVG 1.1 does not support it officially, but SVG 2.0, that is being worked on at the moment, will have it built-in.

SVG elements do not have a lot of means to expose what they are in a non-visual way (besides <title> and @

Exposing from Web Components

Web Components, without going into too much detail, are custom HTML elements that can be created from JavaScript. For example, if <button> does not suit your use-case, you can create a <my-custom-button> element.

At the moment, there are two ways of new element creation:

- an element based on an existing element (i.e.

, but…). It inherits its properties/roles from the existing element if possible - a completely new element. This inherits no properties/roles, so those will have to be added by developer that creates the element.

The first method was recently nominated to be dropped from the specification (see also Bruce Lawson’s article about why he considers this in violation with HTML’s priority of constituencies, as well as the many comments for both sides of the debate).

Again, like <span> s used as buttons and with SVG, these custom elements, especially those not inherited from existing elements, scream for more properties and relations to be exposed to the accessibility tree. Some more info on how to do that in the Semantics section of the spec.

“Code like you give a damn”

Léonie ended her talk with a positive note: to build accessible websites, there is no need to compromise on functionality or design, as long as you “code like you give a damn”. This showed from her examples: many elements, like <button> expose to the accessibility trees, they come with some free accessibility features. And even if you use elements that do not come with built-in accessibility features, you can still use ARIA to expose useful information about them to the accessibility tree.

Personally, I think the best strategy is to always use elements what they are used for (e.g. I would prefer using a <button type="button"> for a button to using a supplemented with ARIA). In other words: I think it would be best to write meaningful HTML where possible, and resort to ARIA only to improve those things that don’t already have meaning (like SVG, Web Components or even the <span> s outputted by the front-end framework you may be using).

Originally posted as The accessibility tree on Hidde's blog.

The web is fast by default, let’s keep it fast

A major web corporation recently started serving simplified versions of websites to load them faster1. Solving which problem? The slowness of modern websites. I think this slowness is optional, and that it can and should be avoided. The web is fast by default, let’s keep it fast.

Why are websites slow?

There are many best practices for web performance. There are Google’s Pagespeed Insights criteria, like server side compression, browser caching, minification and image optimisation. Yahoo’s list of rules is also still a great resource.

If there is so much knowledge out there on how to make super fast websites, why aren’t many websites super fast? I think the answer is that slowness sneaks into websites, because of decisions made by designers, developers or the business. Despite best intentions, things that look like great ideas in the meeting room, can end up making the website ‘obese’ and therefore slow to end users.2 Usually this is not the fault of one person.3 All sorts of decisions can quietly cause seconds of load time to be added:

- A designer can include many photos or typefaces, as part of the design strategy and add seconds

- A developer can use CSS or JavaScript frameworks that aren’t absolutely necessary and add seconds

- A product owner can require social media widgets to be added to increase brand engagement and add seconds

Photos and typefaces can make a website much livelier, frameworks can be incredibly useful in a developer’s workflow and social media widgets have the potential to help users engage. Still, these are all things that can introduce slowness, because they use bytes and requests.

An example: an airline check-in page

To start a check-in, this is the user input KLM needs in step one:

- ticket number

- flight number

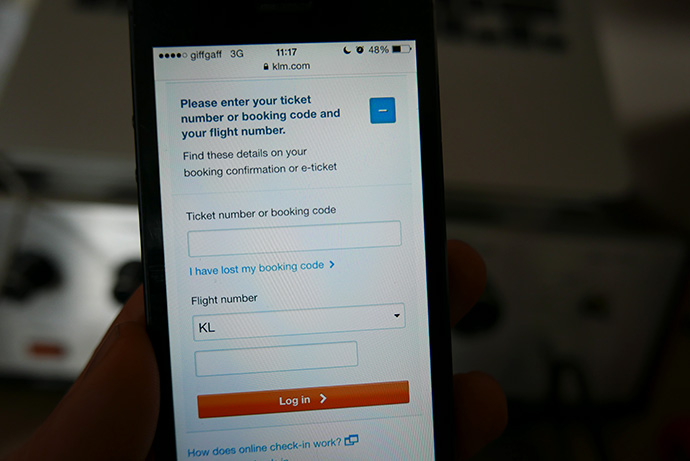

What the check-in page looks like

What the check-in page looks like

For brevity, let’s just focus on this first step and see how it is done. What we would expect for us to submit the above details to KLM, is to be presented with a form that displays a field for each. However, at the time of writing, the check-in page of KLM.com presents us with:

- 151 requests

- 1.3 MB transferred

- lots of images, including photos of Hawaii, London, Rome, palm trees and phone boxes, various KLM logos, icon sprites and even a spacer gif

- over 20 JavaScript files

From the looks of it, more bytes are being transferred than absolutely necessary. Let me emphasise, by the way, that this thing is cleverly put together. Lots of optimising was done and we should not forget there are many, many things this business needs this website to do.

On a good connection, it is ready for action within seconds, and provides a fairly smooth UX. On GPRS however, it took me over 30 seconds to see any content, and 1 minute and 30 seconds to get to the form I needed to enter my details in. This excludes mobile network instabilities. On 3G, I measured 6 and 10 seconds respectively.

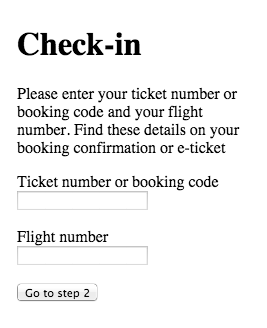

Is there a different way? I mean… what if we JUST use plain HTML? As a thought experiment, not as a best practice or something we would realistically get signed off.

Constructed with just HTML, the page weighs just over 2kb and takes 0.2 seconds to load on GPRS. This is what it would look like:

Just HTML. Alas, it looks boring, but it is extremely fast

Just HTML. Alas, it looks boring, but it is extremely fast

This is the web in its default state, and it is very fast. No added styles or interactions, just HTML. I’m not arguing we should serve plain HTML, but we should realise that everything that is added to this will make the page slower. There is plenty one can add before worrying about slowness: adding a logo, colours and maybe even a custom font can still leave us with a very fast page.

Designing a fast website does not have to be boring at all. As Mark Skinner of cxpartners said, “it’s about being aware of the performance cost of things you add and being deliberate with your choices”.

Performance budgets to the rescue

In a world where speed is the most important aspect of a website, the web can be incredibly fast (plain looking, but incredibly fast). If branding and business needs are taken into account, websites will be slower. As long as everyone involved is aware of that, this is a challenge more than it is a problem.

The key question here, is how much slowness we can find acceptable. Just like a family can set a budget for how much spending they find acceptable, web teams can set a budget for how much slowness we find acceptable. Performance budgets (see Tim Kadlec’s post about this) are a great method for this.

The idea of a performance budget, as Tim explains, is just what it sounds like: ‘you set a “budget” on your page and do not allow the page to exceed that.’ Performance budgets can be based on all kinds of metrics: load time in seconds, or perhaps page size in (kilo)bytes or number of HTTP requests. They make sure everyone is aware of performance, and literally set a limit to slowness.

Agencies like Clearleft and the BBC (‘make the website usable [on GPRS] within 10 seconds’) have shared their experiences with using performance budgets. Advantages of setting a budget, they say, is that it ensures performance is part of the conversation. With the budget, avoiding additions that cause slowness no longer depends on a single developer, it becomes a team’s commitment. With the Grunt plugin it can even be part of the build workflow and out-of-budget additions would, in theory, never make it to production.

Conclusion

The web is not slow by default, but still, many websites have ended up being slow. Apart from the best practices that can often be automated, there are many human decisions that have impact on page speed. A way to make page speed part of the conversation and optimising it part of a website’s requirement, is to set a performance budget.

Update 02/07/2015: Someone pointed me at this page that provides a lighter check-in option

Links

- Setting a performance budget by Tim Kadlec

- Responsive design on a budget by Mark Perkins (Clearleft)

- 8 tips for designing a faster website by Mark Skinner (cxpartners)

- Design decisions through the lens of a performance budget by Yesenia Perez-Cruz (video of her talk at Smashing Conference Freiburg 2014)

Notes

1 Or as Benjamin Reid tweeted: ‘Facebook doesn’t think the web is slow. That’s their “legitimate” reason to stop users navigating off facebook.com. It looks better for them to say that rather than “we’re opening external websites in popups so that you don’t leave our website”.’

2 As Jason Grigsby said

3 As Maaike said (lang=nl)

Originally posted as The web is fast by default, let’s keep it fast on Hidde's blog.

Solving problems with CSS

Writing CSS is, much like the rest of web development, about solving problems. There’s an idea for laying out content, the front-end developer comes up with a way to get the content marked up, and she writes some CSS rules to turn the marked up content into the lay-out as it was intended. Simple enough, until we decide to outsource our abstraction needs.

TL;DR: I think there is a tendency to add solutions to code bases before carefully considering the problems they solve. Abstraction and the tooling that make them possible are awesome, but they do not come without some problems.

When going from paper, Photoshop, Illustrator or whatever into the browser, we use HTML, CSS and JavaScript to turn ideas about content, design and behaviour into some sort of system. We solve our problems by making abstractions. We don’t style specific page elements, we style classes of page elements. Some abstract more from there on, and generate HTML with Haml templates, write CSS through Sass or LESS or use CoffeeScript to write JavaScript.

I work at agencies a lot, so in my daily work I see problems solved in lots of different ways. Some choose to enhance their workflow with preprocessors and build tools, some don’t. All fine, many roads lead to Rome. Often, specifics like grids or media query management (apparently that is a thing) are outsourced to a mixin or Sass function. With so many well-documented libraries, plug-ins and frameworks available, there’s a lot of choice.

What tools can do

Libraries like Bourbon for Sass have lots of utilities that are solutions to solve specific problems. Their mixins can do things like:

@linear-gradient($colour,$colour,$fallback,$fallback_colour) which is transformed into a linear-gradient preceded by a -webkit prefixed version and a fallback background colour. Someone found it would be good to outsource typing the fallback background colour, the prefixed one and then the actual one. So they came up with a solution that involves typing the gradient colours and the fallback colour as arguments of a mixin.

This kind of abstraction is great, because it can ensure all linear-gradient values in the project are composed in the same, consistent way. Magically, it does all our linear gradienting for us. This has many advantages and it has become a common practice in recent years.

So, let’s import all the abstractions into our project! Or shouldn’t we?

Outsourcing automation can do harm

Outsourcing the automation of our CSS code can be harmful, as it introduces new vocabulary, potentially imposes solutions on our codebase that solve problems we may not have, and makes complex rules look deceivably simple.

It introduces a new vocabulary

The first problem is that we are replacing a vocabulary that all front-end developers know (CSS) with one that is specific to our project or a framework. We need to learn a new way to write linear-gradient. And, more importantly, a new way to write all the other CSS properties that the library contains a mixin for (Bourbon comes with 24 at the time of writing). Quite simple syntax in most cases, but it is new nonetheless. Sometimes it looks like its CSS counterpart, but it accepts different arguments. The more mixin frameworks in a project, the more new syntax to learn. Do we want to raise the requirement from ‘know CSS’ to ‘know CSS and the list of project-related functions to generate it’? This can escalate quickly. New vocabulary is potentially harmful, as it requires new team members to learn it.

It solves problems we may not have

A great advantage of abstracting things like linear-gradient into a linear-gradient mixin, is that you only need to make changes once. One change in the abstraction, and all linear-gradients throughout the code will be outputted differently. Whilst this is true, we should not forget to consider which problem this solves. Will we need to reasonably often change our linear-gradient outputs? It is quite unlikely the W3C decides linear-gradient is to be renamed to linear-grodient. And if this were to happen, would I be crazy if I suggested Find and Replace to do this one time change? Should we insist on having abstractions to deal with changes that are unlikely to happen? Admittedly, heavy fluctuation in naming has happened before (looking at you, Flexbox, but I would call this an exception, not something of enough worry to justify an extra abstraction layer.

Doesn’t abstracting the addition of CSS properties like linear-gradient qualify as overengineering?

It makes complex CSS rules look simple

Paraphrasing something I’ve overheard a couple of times in the past year: “if we use this mixin [from a library], our problem is solved automatically”. But if we are honest, there is no such thing.

Imagine a mathematician shows us this example of his add-function: add(5,2). We would need no argument over the internals of the function, to understand it will yield 7 (unless we are Saul Kripke). Adding 5 + 2 yields 7.

Now imagine a front-end developer showing us their grid function: grid(700,10,5,true). As a curious fellow front-end person, I would have lots of questions about the function’s internals: are we floating, inline-blocking, do we use percentages, min-widths, max-widths, which box model have we set, what’s happening?

Until CSS Grids are well supported, we can’t do grids in CSS. Yet we can, we have many ways to organise content grid-wise by using floats, display modes, tables or flexible boxes. Technically they are all ‘hacks’, and they have their issues: floats need clearing, inline-block elements come with spaces, tables aren’t meant for lay-out, etc. There is no good or bad, really. An experienced front-end developer will be able to tell which solution has which impact, and that is an important part of the job.

CSS problems are often solved with clever combinations of CSS properties. Putting these in a black box can make complex things look simple, but it will not make the actual combination of CSS properties being used less complex. The solution will still be the same complex mix of CSS properties. And solving bugs requires knowledge of that mix.

Solve the problem first

When we use a mixin, we abstract the pros and cons of one solution into a thing that can just do its magic once it is included. Every time the problem exists in the project, the same magic is applied to it. Given a nice and general function name is used, we can then adjust what the magic is whenever we like. This is potentially super powerful.

All I’m saying is: I think we add abstractions to our projects too soon, and make things more complex than necessary. We often overengineer CSS solutions. My proposal would be to solve a problem first, then think about whether to abstract the solution and then about whether to use a third-party abstraction. To solve CSS problems, it is much more important to understand the spec and how browsers implemented it, than which abstraction to use (see also Confessions of a CSS expert). An abstraction can be helpful and powerful, but it is just a tool.

Originally posted as Solving problems with CSS on Hidde's blog.

Making our websites even more mobile friendly

From 21 April, Google will start preferring sites it considers “mobile friendly”. The criteria are listed in a blog post and Google provide a tool for web masters to check whether they deem websites eligible for the label.

First, we should define what we are trying to be friendly for here. What’s the ‘mobile’ in ‘mobile friendly’? Is it people on small screen widths, people on the move, people with a slow connection? The latter is interesting, as there are people using their fast home WiFi on a mobile device on the couch or loo. There are also people who access painfully slow hotel WiFi on their laptops.

Assumptions are pretty much useless for making decisions about what someone is doing on your site. Mobile, as argued before by many, is not a context that helps us make design decisions. We’ll accept that for the purpose of this article, and think of mobile as a worst-case scenario that we can implement technical improvements for: people on-the-go, using small devices on non-stable connection speeds.

Great principles to start with

So what are Google’s criteria for mobile friendliness? According to their blog post, they consider a website mobile friendly if it:

- Avoids software that is not common on mobile devices, like Flash

- Uses text that is readable without zooming

- Sizes content to the screen so users don’t have to scroll horizontally or zoom

- Places links far enough apart so that the correct one can be easily tapped

(Source)

Websites that stick to these criteria will be much friendlier to mobile users than websites that don’t. Still, do they cover all it gets to be mobile friendly?

It passes heavy websites, too

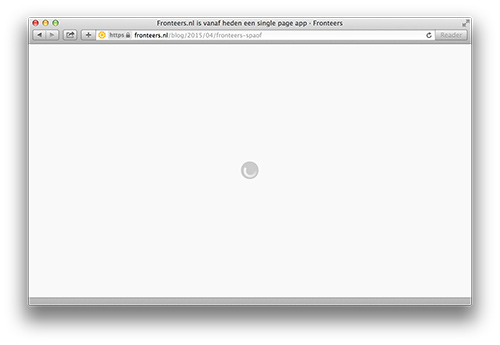

At Fronteers, we celebrated April Fool’s by announcing, tongue-in-cheek, that we went all Single Page App. We included as many JavaScript libraries into the website as we could, without ever actually making use of them. It made the page much heavier in size. We also wrapped all of our markup in elements, with no actual JavaScript code to fetch and render content. The site became non-functional for users with JavaScript on. External scripts were included in the <head> of the page, so that their requests would block the page from rendering. With JavaScript turned off, the site was usable as usual, with JavaScript on, all the user saw was an animated spinner gif.

All the user saw was an animated spinner gif

All the user saw was an animated spinner gif

Probably not particularly funny, but it showed a problem that many modern websites have: loading content is made dependent on loading JavaScript, and lots of it. This is not user friendly, and certainly not friendly to users on wobbly mobile connections. In our extreme case, the content was made inaccessible. Still, as Krijn Hoetmer pointed out on Twitter this morning, the joke —still live on the page announcing it (view the source) — passed Google’s test for mobile friendliness:

Nope, Google, a media query doesn’t make a site “Mobile-friendly”. Your algo needs some love: google.com/search?q=site:… pic.twitter.com/GPgEfkpKLV

I think he is right, the algorithm could be improved. This is not trivial, because the algorithm has no way to find out if we intended to do anything more than display a spinner. Maybe we really required all the frameworks.

The tweet inspired me to formulate some other criteria that are not currently part of Google’s algorithm, but are essential for mobile friendliness.

Even more friendly mobile sites

There are various additional things we can do:

Minimise resources to reach goals

Slow loading pages are particularly unfriendly to mobile users. Therefore, we should probably:

- Be careful with web fonts

Using web fonts instead of native fonts often cause blank text due to font requests (29% of page loads on Chrome for Android displayed blank text). This is even worse for requests on mobile networks as they often travel longer. Possible warning: “Your website’s text was blank for x seconds due to web fonts” - Initially, only load code we absolutely need

On bad mobile connections, every byte counts. Minimising render-blocking code is a great way to be friendlier to mobile users. Tools like Filament’s loadCSS / loadJS and Addy Osmani’s Critical are useful for this. Possible warning: “You have loaded more than 300 lines of JavaScript, is it absolutely needed before content display?” - Don’t load large images on small screens

Possible warning: “Your website shows large images to small screens”

Google has fantastic resources for measuring page speed. Its tool Pagespeed Insights is particularly helpful to determine if you are optimising enough. A reason not to include it in the “mobile friendly” algorithm, is that speed is arguably not a mobile specific issue.

Use enough contrast

If someone wants to read your content in their garden, on the window seat of a moving train or anywhere with plenty of light, they require contrast in the colours used. The same applies to users with low brightness screens, and those with ultramodern, bright screens who turned down their brightness to deal with battery incapacity.

Using grey text on a white background can make content much harder to read on small screens. Added benefit for using plenty of contrast: it is also a good accessibility practice.

Again, this is probably not mobile specific; more contrast helps many others.

Attach our JavaScript handlers to ‘mobile’ events

Peter-Paul Koch dedicated a chapter of his Mobile Web Handbook to touch and pointer events. Most mobile browsers have mouse events for backwards compatibility reasons (MWH, 148), he describes. That is to say, many websites check for mouse clicks in their scripts. Mobile browser makers decided not to wait for all the developers to also check for touch behaviour. So, mobile browser makers implemented a touch version of the mouse click behaviour, so that click events also fired on touch.

Most mobile browsers listen to touch events, like touchstart or gesturechange (iOS). So maybe we could measure mobile friendliness by checking if such events are listened to? This is a tricky one, because a script that only listens to click events can be mobile friendly, because of backwards compatibility.

Depending on the functionality, JavaScript interactions can be improved by making use of mobile specific events. Carousels (if you really need to) are a good example of this: adding some swipe events to your script can make it much more mobile friendly. Or actually, like the two above, it would make it friendlier for all users, including those with non-mobile touch screens.

Even more friendly sites

Page speed, colour contrast and touch events may not be mobile specific, but I would say that goes for all four of Google’s criteria too. Legible text helps all users. Tappable text also helps users of non-mobile touch screens.

If we are talking about improving just for mobile, Google’s criteria are a great start. But we need to work harder to achieve more mobile friendliness. Above, I’ve suggested some other things we should do. Some can be measured, like improving load times and providing enough contrast. These things are friendly to all users, including mobile ones. Other things will have to be decided case by case, like including ‘mobile’ events in JavaScript, but probably also how much of our CSS or JavaScript is critical. As always, it depends.

Originally posted as Making our websites even more mobile friendly on Hidde's blog.