Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

World IA Day 2016 in Bristol

This weekend I attended World IA Day in Bristol. The event is organised simultaneously in 61 locations across 31 countries. The local one was put together by Nomensa, an awesome Bristol web agency whom I had the pleasure of freelancing with for 3 months last year.

The day offered a variety of talks: some more philosophical, others more practical. The overarching theme of the day was ‘information everywhere, architects everywhere’. Talks focused on what architecture is (and whether ‘architecting’, as Kanye West used it, is indeed a verb). It was about what it means that in the digital age, information can really go everywhere.

Simon Norris - From taxonomy to data and beyond

Simon’s talk gave us an interesting overview of the history of information architecture (IA). According to Simon, four paradigms characterise the development of IA: Classic IA, User-generated IA, Pervasive IA and Inversion. He related each one to a change of context.

First spoken about in the sixties at companies like IBM, the discipline of IA started with the popularisation of the phrase by Richard Saul Wurman, and the publication of the book ‘Information Architecture’ by Morville and Rosenfield, also known as the Polar Bear Book.

Simon considers IA as a ‘sister’ discipline of UX (separately, like chemistry and physics are separate disciplines). One does not supersede the other, they work together. IA is about the blending of the immaterial and the material, Simon said. In this view information itself is completely shapeless, and giving it shape is what IA is about.

Simon discussed these four waves of IA:

-

Classic IA - Context: the web was quickly becoming the most popular technology ever. Classic IA was about what to equip designers with to make sense of all the information that needs to go on a website. Simon said that for him, Classic IA was about defining taxonomies to aid the design of websites that support human decision making.

-

User generated IA - Context: the web had become a global phenomenon in many ways, it was bigger than what anyone expected. Another shift happened: User generated IA. It was almost the opposite of Classic IA: it was user orientated not designer orientated. Users were enabled to make their own taxonomies and with that, shape their own experiences. Example: delicio.us (now Delicious), the bookmarking website, lets users save URLs and manage them within taxonomies like tags and categories.

-

Pervasive IA - Context: people started to use computers everywhere. It was no longer a discrete activity, computing had become ubiquitous, and interaction started happening ‘cross channel’. IA was no longer about labeling and hierarchies, it became about sense making and place making. Resmini and Rosati wrote ‘Pervasive Information Architecture’. IA now had to consider changing and emerging experience across channels.

- Inversion - Context: digital is now influencing the physical world. The fourth wave is about ‘inversion’. There is now so much data, ‘big data’, that we could do analysis on, that we are urged to look at information in a completely new way, Simon said.

Simon recommended reading “A brief history of information architecture” by Resmini/Rosati (PDF).

Shaula Zanchi - The world is greater than the sum of its parts

Shaula works in ‘physical’ architecture and talked about how internal information is managed at her company. For each project there is a lot of information that they need to keep track of. One example of information is keeping track of samples used in the architectural process: which they had, where they were, where they came from, et cetera.

They began making sense of their information and the relationships within it through a spreadsheet. Then they started using a database with some PHP, as a kind of Excel plus. They then started adding layout kind of things to what they had, so that it could look and feel more like what they now call Sample Library. It all became part of the bigger intranet project.

A very interesting case study!

Team BBC

The next talk up was by what Simon called “Team BBC”: four smart people involved with the BBC’s information architecture.

Dan Ramsden talked about blending the day’s theme, ‘information everywhere’, with another: ‘uncertainty’. At BBC, he said, they literally have millions of pages online. This is a lot of content and information. The ratio of content producers to designers is roughly 83:1. Projects vary from simple projects with a clear direction and scope to more complex ones, with many uncertainties. Information architecture helps them hugely with these challenges. The most important IA adds to the BBC, Dan concluded, is that by defining a structure, we create meaning.

Luisa Sousa then talked about joining and becoming a User Experience Architect at the BBC. When she first started, she explained, Luisa felt like being in a box where she couldn’t move or see much. On her first project, a new website for GEL, she learned to stop worrying about the word ‘architect’ in her job title, and to start being involved as a problem solver, master of questions, designer and jelly bean eater. From her talk, I understood good information architects are able to put on many hats.

Barry Briggs talked about practical aspects of being a user experience architect. He emphasised how complex IA work can be, as there are many gaps between bits of information. He showed how flow charts can help. Not only do they help verifying IA work with stakeholders, they also help with dividing stakeholdership across different parts of the chart. Letting team members and stake holders be involved with specific parts of the flow chart, also aids working in parallel, Barry explained.

Lastly, Cyrièle Piancastelli talked about advocating for UX at BBC. The best user experience, she explained, enables innovation, is an investment and is essential. The best way for user experience (and perhaps information architecture). At the BBC, as Dan also mentioned, there is lots of good content. When you are already sure about your content, the thing that you can make a difference with is how your present it, said Cyrièle. With good IA, we can make a difference.

Karey Helms - Making the invisible physical

Karey talked about how to make sense of complex data driven systems to design enterprise solutions. She discussed what makes enterprise UX so challenging and what physical prototyping is, and showed us some cool example projects.

One of the major challenges Karey’s company had, is that many of their users are ‘situationally disabled’. Whether they are potentially under stress (healthcare patients) or wearing gloves (when working in a warehouse): they can be in complex situations, and interfaces need to be designed appropriately. I think this goes for users outside enterprise as well: we should always design for circumstances that we are aware or unaware of.

Physical prototyping or model making, Karey explained, is used by her company to identify what ‘core components’ of a project are, to situate things in context and to explore interaction modalities.

Karey showed some great and personal examples:

- the ‘party mode’ on her website that corresponds with a Philips Hue light on her desk. Information, she concluded from this project, is emergent, part of an ecosystem and not a fixed modality.

- the ‘burrito’ bot: it analyses use of emoji in personal communication between her and her husband, and then reports who the weeks’ best spouse was at the end of each week. From this she found that information has a large role in the design of systems, but also that it has broader implications and varying levels of fidelity.

Ben Scott-Robinson - Making money out of IA

Ben works for Ordnance Survey, Britain’s ‘national mapping agency’. Making maps, he explained, is in its core all about information architecture. His talk was about how OS makes money from IA. The main thing they produce, he said, clarity of information. Detailed information, in their case, used by the likes of governments and telecom providers.

Despite the IA-like activities being at the core of the company, OS’ website was not ‘generating leads’ or selling products very well. This almost lead to the closure of the website, but this did not happen. They decided to work on a new website and have a strong focus on user testing during the process.

Ben explained OS decided to make ‘happiness of users’ a key metric for their definition of success. Their company’s performance would be judged by how happy their users were. There was an big role for NPS (net promotor score), a number that expresses the chance a customer would recommend your company to others. NPS, they decided, equals happiness. When they first started, the NPS was very low, negative even. Then they started using UX processes like paper prototyping and card sorting. They built a new website, showed it to stakeholders. Some departments were unhappy as their bit wasn’t in the main navigation, but this is where the user testing sessions came in handy: there were many a user testing video they were able to show to back up their decision.

Dan Klyn - Everything needs to be actually architected

The last talk of the day was a great Kanye West-inspired keynote by Dan Klyn. A greatly inspiring talk, about whether architecting is a verb (compared with the word ‘designed’, he said, it is about something more fundamental than design). Dan emphasised that architecture is not design. He also talked about the difference between good design and better design, which he said is immeasurable.

Dan Klyn

Dan Klyn

The reason we don’t call architects something like ‘building designers’, Dan said, is that they operate on a different level, being the level of human agreement. An interesting challenge in IA Dan mentioned is that of the ‘structural integrity of meaning across contexts’: the ‘mess’ that iTunes currently is, is an example of a product where this needs improvement.

Conclusion

I had a great time at World IA Day 2016 and learned a bunch about information, architecture and information architecture! Practical tips about different approaches and working together, but also theoretical ideas about the meaning of information architecture concepts. Also, I should definitely go and read the Polar Bear book.

Originally posted as World IA Day 2016 in Bristol on Hidde's blog.

Turning off Heartbeat in WordPress made my day!

Heartbeat API is a thing built into WordPress that sends a POST request every 15 seconds. It allows for interesting functionalities like revision tracking, but can also dramatically slow things down and even block editors from editing content (if your connection is quite slow).

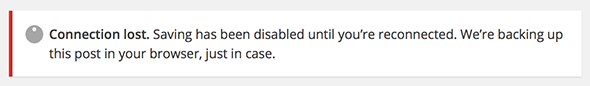

The “Edit” pages in WordPress use the Heartbeat API to detect connection loss. If they detect you’ve lost your connection, your ‘Update’/‘Publish’ button will get disabled until your connection is back.

Why?

“Connection lost” message on slow connections

When I was working on a WordPress site this week, I accessed the internet through my 3G MiFi, and added a VPN for security (the less glamorous side of working remotely). It resulted in seeing the ‘Connection lost’ message all the time. It would usually appear before I could make any changes, and never disappear. In which case it stopped me from editing content.

! The error message

! The error message

High CPU usage

Others comment that Heartbeat leads to high CPU usage: imagine having multiple instances of WordPress edit pages open in a browser, each sending its own POST requests every 15 seconds.

Turning Heartbeat off

Only when I just turned the whole thing off, I was able to make changes to my page. Turning Heartbeat off can be done by simply deregistering the script:

add_action( 'init', 'remove_heartbeat');

function remove_heartbeat() {

wp_deregister_script('heartbeat');

}(via Aditya Nath Jha

Originally posted as Turning off Heartbeat in WordPress made my day! on Hidde's blog.

Making conference videos more accessible

If conference videos are made more accessible, they can be shared with a wider audience. This is a great way to add value! Most Fronteers 2015 videos are now available with captions and transcripts. In this post I will explain why we did it, how we got our transcripts made and what happened next.

At Fronteers, we have had our videos transcribed in the past 2011, 2012, but it was quite a time-consuming process and we’ve not always been able to find volunteers for it. In recent years, the process has improved a bit, so this year I thought it would be good to have them made again.

What and why

To make a video more accessible, WebAim recommends having both captions and transcripts.

A caption is like a subtitle, but in the same language as the video. It contains whatever is said in the video, and other sounds, such as laughter, applause and description of any music that is played.

A transcript is a textual alternative for audio and video. On the Fronteers site, we use the content of the caption file and display it underneath the video.

Captions and transcripts can benefit:

- people with partial or total inability to hear

- people for whom the video’s language is not their first

- people who do not have time to watch the video, prefer reading it or want to search for a specific thing a speaker said

- people watching the video in a noisy environment

- your website’s SEO optimisation strategy for search engines1! (really)

Amara via Vimeo

For our transcripts this year, we have been making use of a service called Amara. It is integrated into Vimeo, which makes the process of ordering very convenient (we host our videos there).

We used Amara’s paid service, but, at the time of writing, they also give users access to their editor on Vimeo, so that they can DIY the transcripts. Or you can access the same tool on Amara.org and subtitle videos hosted anywhere (many formats supported). Both are free, but cost more time per transcript.

Amara is bigger than just their Vimeo integration: they are a project of a not-for-profit organisation that aims to ‘build a more open, collaborative world’. In this post I will focus on how to do it with the version built-in to Vimeo.

The process

The Amara service can be used from within Vimeo. The way it works is that, as the uploader, you go to your videos’ settings and under “Purchase Amara professional services”, you click “Purchase”. You then select the language that you require, choose a price tier and enter payment details.

You can also add a comma separated list of technical terms, to make sure the transcript reflects their spelling correctly. As an experiment, I decided to leave this field empty.

Purchase button on Vimeo

Purchase button on Vimeo

After submitting a video for transcription, each one took 3-6 working days to show up. The week after I had ordered them, they kept slowly coming in, giving me the time to check each one (see below). The quality was surprisingly good, with only very few minor corrections needed. This was despite not supplying a list of technical terms.

When we were happy with the transcript, we also uploaded the video to our own website, where we included:

- the video (as a

, obvs) - the subtitle file as captions (a

) - the transcript (which in our case was just the captions file as text)

(Example: Digital governance by Lisa Welchman)

In the front-end outputted by our CMS, Krijn built something nifty to make it so that when you click a sentence in the transcript, the video skips to that part of the talk. Check out the example above to see it in action, it is very cool!

If you want to do something similar, it is good to know that the caption that shows up in Vimeo can be downloaded as a WebVTT file. This is ‘just’ a text file with time stamps and sentences, so it can be opened and updated in a text editor of choice.

QA

In our case, we paid for our transcripts. The results were very good, and almost ready to go live. Just before that, I have gone through a few steps manually for each transcript:

- search for

[INAUDIBLE]and have a listen to see if it really is inaudible. Sometimes it was added when the speaker said a technical term very fast (gulp.js,console.log()) - search for

[?, these are words that the transcriber was unsure about. Again, these could be technical terms. If the video is about web development and you’re a web developer, you can likely fix it. - scroll through and gloss over the text

!/_images/vimeo-amara-.jpg(Amara interface on Vimeo)! Amara’s handy interface to check and adjust your captions

Some notes

- At the time of buying, Basic, Professional or Full Service captions were priced at $1.70, $2.80 and $3.95 per minute respectively (difference is in how many proofreaders are used), so it is not very cheap. A conference video (45-60 minutes) will cost between $100 and $150.

- From the Vimeo interface, you cannot get all languages transcribed. Our conference videos were in English, which was supported. Many of our meetup videos are in Dutch, which is not supported.

- I was amazed at how good the transcribers were at getting technical terms right, words like SVGOMG, Sass and JavaScript were spelled and capitalised correctly and consistently so. Ideal for when pedantry does occur within your target audience!

- Using Amara’s “Professional” tier, leaving the technical terms field blank still gives great results

- We used Casting Words in the past, they work out slightly cheaper and offer integration with FTP and an API (but are not built into Vimeo)

So, that’s it. I hope this helps conference organisers in deciding whether and how to transcribe their conference videos. If you have experience with other services or workflows, please do leave a comment below.

Edit 26/01/2018: unfortunately, it is no longer possible to do the above through Vimeo.

Originally posted as Making conference videos more accessible on Hidde's blog.

The website as an instantiation of your design system

In his talk at Beyond Tellerand last year, web designer Brad Frost talked about the website “as an instantiation of your design system”. I really liked that idea.

Design can be defined by many things: it is a thought process, the result of abstract thinking, something that requires research and a sense of style. From a practical point of view, it can be described in terms of the materials it is made of. Paint, wood, glass, ink… This is slightly different for web design. Web design, in particular, is made of some very specific materials: HTML, CSS, JavaScript, typefaces and images.

Design on the web, more than any other type of design, can be documented in a way that is powered by the materials it is made of. Pattern libraries can do this.

Pattern libraries

A pattern library is a set of components, in which each component can include:

- Documentation

- Mark-up in HTML (or Twig or Haml or Mustache)

- Style in CSS (or Sass or Less or Styles)

- Scripts in JavaScript (or Coffee Script)

- Images

Each component has at least documentation and mark-up.

The set of components, as a whole, describes the design system that exists in your website. The components, plus perhaps a couple of files like typefaces, a logo and an icon set (although they could be components of their own).

Advantages

The advantages of separating your design system out as front-end components are plentiful:

- great reference for all people involved in the project

- potentially a better workflow, as there is only one place where common patterns are created

- easier to spot and avoid inconsistencies in both design and code (‘Oh wait, we’ve already got a datepicker!’, ‘Actually, we can reuse most of that existing markup for this new button style’)

- more testable as everything is abstracted and nicely separated and organised, this makes it easier for a script (or anyone) to test

Zombie style guides

To create a style guide as an overview of your website’s design system and the corresponding code is one thing. To maintain it, is another. In her Fronteers 2015 talk, Anna Debenham referred to a phenomenon known as zombie style guides, style guides that live separate from the web project they power, and are not actively maintained. They are no longer as useful as they were at the start of the project.

To avoid that, a style guide should be what powers your actual website(s), so that your website(s) become instance(s) of your design system.

The website as an instantiation of your design system

This is what Brad Frost suggested in this talk at Beyond Tellerand in Düsseldorf (Video, scroll to 39:00):

“The website is one instantiation of your design system”

I think this brilliant. In the ideal set up, there is a set of components, and then those components are used in places. The set is built, updated, improved, refactored etc separately from the places it is used in. The website, but also a front-end style guide are just examples of places.

Brad quotes Nathan Curtis:

“A style guide is an artifact of design process. A design system is a living, funded product with a roadmap & backlog, serving an ecosystem.”

Copy/pasting mark-up vs “real” instantiation

One way a website could be an instantiation of a design system, is if all markup in the site is copied from the style guide. The copy/paste method is easiest to set up.

A much better and more ideal way, is if the site uses code to grab a copy of the actual markup for a component. This markup could live in its own repository so that it can be modified, refactored and improved. For example:

includeMyComponent('button', { text: "Click here" })could render as this today:

<span class="button">Click here</span>and render as this tomorrow, after an update to the component library:

<button class="button">Click here</button>New mark-up, same include function.

The holy grail, Frost concludes, is a “magical setup” that contains “all the lego bricks of a site”, and if we make a change, anywhere that lego brick is updated, it just magically updates. Like the example above. Ian Feather and his team at Lonely Planet have built a system that can do this, with their API for components.

The front-end style guide

The front-end style guide, like the website, can also be seen as an instantiation of the design system. It is just another place that consumes your organisation’s set of components.

Documentation

There is one important difference though: a front-end style guide should, in my opinion, serve as documentation. So not only should it consume the components themselves, it should consume components with their documentation.

The person who builds a component, will have to write its documentation. This is essential, as a few month’s later, they may have left the team. Or they may still be on it, but have forgotten about what the component was for.

Documentation of a component should explain what it is, what it is used for and what its options/parameters are.

Conclusion

To summarise my thoughts: I think web design is a special type of design as it can be documented with the same materials it is made of: markup, stylesheets, scripts et cetera. This can be done by structuring the design in the form of a system of components. This system can then power both the website and a showcase of documented components. Statically, or, ultimately, dynamically.

For more info on different types of style guides and approaches to building ones that ‘live’, I can recommend watching Anna’s talk at Fronteers and Brad’s talk at Beyond Tellerand:

- Anna Debenham – Front-end Style Guides (Fronteers, Amsterdam, 2015, includes transcript so you can read instead of watch)

- Brad Frost – Style Guide Best Practices (Beyond Tellerand, Düsseldorf, 2015)

Originally posted as The website as an instantiation of your design system on Hidde's blog.

JSCS vs JSHint

JSHint helps you enforce code correctness, whereas JSCS helps you enforce a code style.

JSHint is deprecating its code style related features and plans to remove them from the next major releases (see docs). Therefore, it makes sense to use both JSCS and JSHint. (Thanks Alex for pointing me at this)

Originally posted as JSCS vs JSHint on Hidde's blog.