Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Using JavaScript to trap focus in an element

For information on how to accessibly implement the components I’m working on, I often refer to WAI-ARIA Authoring Practices specification. One thing this spec sometimes recommends, is to trap focus in an element, for example in a modal dialog while it is open. In this post I will show how to implement this.

Some history

In the early days of the web, web pages used to be very simple: there was lots of text, and there were links to other pages. Easy to navigate with a mouse, easy to navigate with a keyboard.

The modern web is much more interactive. We now have ‘rich internet applications’. Elements appear and disappear on click, scroll or even form validation. Overlays, carousels, AJAX… most of these have ‘custom’ behaviour. Therefore we cannot always rely on the browser’s built-in interactions to ensure user experience. We go beyond default browser behaviour, so the duty to fix any gaps in user experience is on us.

One common method of ‘fixing’ the user’s experience, is by carefully shifting focus around with JavaScript. The browser does this for us in common situations, for example when tabbing between links, when clicking form labels or when following anchor links. In less browser-predictable situations, we will have to do it ourselves.

When to trap focus

Trapping focus is a behaviour we usually want when there is modality in a page. Components that could have been pages of their own, such as overlays and dialog boxes. When such components are active, the rest of the page is usually blurred and the user is only allowed to interact with our component.

Not all users can see the visual website, so we will also need to make it work non-visually. The idea is that if for part of the site we prevent clicks, we should also prevent focus.

Some examples of when to trap focus:

- user opens a modal in which they can pick a seat on their flight, with a semitransparent layer underneath it

- user tries to submit a form that could not be validated, and is shown an error message; they can only choose ‘OK’ and cannot interact with the rest of the page

- user opens a huge navigation menu, the background behind the navigation is blurred (“Categorie kiezen” at Hema.nl)

In these cases we would like to trap focus in the modal, alert or navigation menu, until they are closed (at which point we want to undo the trapping and return focus to the element that instantiated the modal).

Requirements

We need these two things to be the case during our trap:

- When a user presses

TAB, the next focusable element receives focus. If this element is outside our component, focus should be set to the first focusable element in the component. - When a user presses

SHIFT TAB, the previous focusable element receives focus. If this element is outside our component, focus should be set to the last focusable element in the component.

Implementation

In order to implement the above behaviour on a given element, we need to get a list of the focusable elements within it, and save the first and last one in variables.

In the following, I assume the element we trap focus in is stored in a variable called element .

Get focusable elements

In JavaScript we can figure out if elements are focusable, for example by checking if they either are interactive elements or have tabindex .

This gives a list of common elements that are focusable:

var focusableEls = element.querySelectorAll('a[href]:not([disabled]), button:not([disabled]), textarea:not([disabled]), input[type="text"]:not([disabled]), input[type="radio"]:not([disabled]), input[type="checkbox"]:not([disabled]), select:not([disabled])');This is an example list of common elements; there are many more focusable elements. Note that it is useful to exclude disabled elements here.

Save first and last focusable element

This is a way to get the first and last focusable elements within an element :

var firstFocusableEl = focusableEls[0];

var lastFocusableEl = focusableEls[focusableEls.length - 1];We can later compare these to document.activeElement , which contains the element in our page that currently has focus.

Listen to keydown

Next, we can listen to keydown events happening within the element , check whether they were TAB or SHIFT TAB and then apply logic if the first or last focusable element had focus.

var KEYCODE_TAB = 9;

element.addEventListener('keydown', function(e) {

if (e.key === 'Tab' || e.keyCode === KEYCODE_TAB) {

if ( e.shiftKey ) /* shift + tab */ {

if (document.activeElement === firstFocusableEl) {

lastFocusableEl.focus();

e.preventDefault();

}

} else /* tab */ {

if (document.activeElement === lastFocusableEl) {

firstFocusableEl.focus();

e.preventDefault();

}

}

}

});Alternatively, you can add the event listener to the first and last items. I like the above approach, as with one listener, there is only one to undo later.

Putting it all together

With some minor changes, this is my final trapFocus() function:

function trapFocus(element) {

var focusableEls = element.querySelectorAll('a[href]:not([disabled]), button:not([disabled]), textarea:not([disabled]), input[type="text"]:not([disabled]), input[type="radio"]:not([disabled]), input[type="checkbox"]:not([disabled]), select:not([disabled])');

var firstFocusableEl = focusableEls[0];

var lastFocusableEl = focusableEls[focusableEls.length - 1];

var KEYCODE_TAB = 9;

element.addEventListener('keydown', function(e) {

var isTabPressed = (e.key === 'Tab' || e.keyCode === KEYCODE_TAB);

if (!isTabPressed) {

return;

}

if ( e.shiftKey ) /* shift + tab */ {

if (document.activeElement === firstFocusableEl) {

lastFocusableEl.focus();

e.preventDefault();

}

} else /* tab */ {

if (document.activeElement === lastFocusableEl) {

firstFocusableEl.focus();

e.preventDefault();

}

}

});

}In this function, we have moved the check for tab to its own variable (thanks Job), so that we can stop function execution right there.

Further reading

See also Trapping focus inside the dialog by allyjs, Dialog (non-modal) in WAI-ARIA Authoring Practices and Can a modal dialog be made to work properly for screen-reader users on the web? by Everett Zufelt.

Originally posted as Using JavaScript to trap focus in an element on Hidde's blog.

On initialising JavaScript from markup

In Don’t initialise JavaScript automagically, Adam Silver argues that we should not rely on markup to trigger bits of JavaScript. I disagree with the advice he gives, and think markup is great place to trigger behaviour. Where else?

A quick disclaimer up front: I believe that when it comes to how to trigger JavaScript, there is no good or bad. There is personal preference though, and mine is a markup-based approach.

In this post I will go into three of Adam’s concerns with that approach. They are about what behaviour is being triggered, how many times and whether hiding complexity is a problem. His post does not go into any non-markup-based initialisation methods, so I can only guess what such methods would involve.

What you’re triggering

With markup to trigger behaviour, Adam explains, it is harder to know what you’re initialising. I think this depends on how your declare the behaviour. Enforcing a solid naming approach is essential here.

This is an approach I like:

<a href="#section1"

data-handler="open-in-overlay">

Section 1</a>Let’s assume a website consistently uses the data-handler attribute (see my earlier post about handlers), with as its value a verb that corresponds to a function name. In the codebase for that website, it will be trivial to see what you are initialising.

In the example, the initialised JavaScript will open a thing called “Section 1” in an overlay. The function name is pretty much self-documenting, and it will live wherever your team decided functions to live.

Another approach is the syntax ConditionerJS uses:

<a href="http://maps.google.com/?ll=51.741,3.822"

data-module="ui/Map"

data-conditions="media:{(min-width:40em)} and element:{was visible}"> ... </a>Conditioner (it’s frizz-free) does not use verbs as a naming convention, but expects module names in a data-module attribute. All modules use the same convention for declaring they exist. Again, there is no confusion as to which behaviour is being triggered.

In the above examples agreed upon data attributes are used to declare behaviour. The reason why I think they are intuitive, is that they look very similar to standard HTML. Take this link:

<a href="#section1"

title="Section">

Section</a>We could see this as a ‘link’ module, that has two options set in its attributes: href tells the browser where it needs to take the user, title sets up which text to display in a tooltip when the user hovers a link.

Or this image:

<img src="temple.jpg" alt="Four monks in front of a temple" />This ‘image’ module comes with two settings: src tells the browser where the image is, alt can be used by browsers to display to users if fetching the image fails. With srcset and sizes, even more attributes are available to trigger behaviour.

In summary: custom attributes are great to declare custom behaviour, because HTML already has lots of native attributes that declare native behaviour. This doesn’t mean we’re doing behaviour in HTML: we’re doing behaviour in JavaScript, and are merely using the markup to declare the nature and conditions of this behaviour.

How many times you’re triggering

When you trigger JavaScript for each occurrence of classname or attribute, you do not know how many times you are triggering it, says Adam.

Correct, but is this a problem? This phenomenon is quite common in other parts of our work. In a component based approach to markup, you also don’t know how many times a heading or a <p> is going to be on a given page. In CSS, you also style elements without knowing on which pages they will exist (or not), or how many times.

Hiding complexity

[Defining behaviour in markup] is magical. […] Automagical loops obfuscate complexity. They make things appear simple when they’re not.

It’s unfair to markup-based initialisation concepts to label them ‘magical’, as if that is something we should at all times avoid. The label makes it sound like there is a simpler and more sensical alternative, but is there?

We are always going to be applying script to DOM elements, whether we define where scripts run in the scripts themselves, or in the markup they apply to. Neither is more or less magical.

Besides, if using classes or attributes to trigger behaviour is magical, is using classes to trigger CSS also magical?

For example:

h2 { color: red; }Your browser ‘automagically’ applies a red colour to all the headings. Its algorithms for this are hidden away. That’s good. We can declare a colour, without knowing exactly how our declaration is going to be applied. This is very powerful. It is this simplicity that has helped so many people publish great stuff on the web.

The same goes for my HTML examples earlier. The fact that link title tooltips and alt texts are just attributes, makes them easier to use. The fact that the browser’s logic to ‘use’ them is obfuscated is a benefit, if anything.

Abstracting the complexities of initialisation away also helps to keep code DRY. There is one method for initialisation, which is testable and maintainable. Everything else is just suitable function names declared on well-structured HTML, which themselves are also testable and maintainable.

Conclusion

I think defining behaviour in markup is absolutely fine, and it is probably one of the most powerful ways to define behaviour out there. Looping through elements with specific attributes helps developers write DRY, maintainable and testable JavaScript code. Not looping through elements would do away with most of those advantages, without any clear wins.

There is something magical about how DOM structures work together with the styles and scripts that are applied to them, but that will always be the case, regardless of where our initialisation happens. I would be interested to see examples of approaches that do not use markup to infer what behaviour a script needs to apply where, but until then, I’ll be more than happy to use some of the above methods.

Originally posted as On initialising JavaScript from markup on Hidde's blog.

Leaving the Fronteers board: what happened

This week I resigned from the Fronteers board. I tweeted about it earlier, but didn’t express myself as carefully as I would have liked to do. In this post I hope to explain things properly.

TL;DR: Fronteers members democratically voted to hire an external company ran by two former conference team members to take care of the logistics of its conference organisation. Personally it made sense for me to leave the board as a consequence. I think Fronteers has a bright future, and the decisions made can help make Fronteers more professional, and possibly more fair, as less pressure will be put on volunteers that spend too much time on Fronteers.

Also, there should be no confusion over this: this was a perfectly reasonable proposal, which was accepted by a majority of the Fronteers members who came out to vote. Personally, I feel the decision is bad for Fronteers as an organisation that is multi-faceted: meet-ups, workshops, conferences, a job board and lots of community outreach. It puts the conference and its organisers first by making that facet a paid job, and is bad for the other facets. I suspect less volunteers will be likely to choose and spend a lot of time on Fronteers for free. In a year’s time, I think Fronteers should probably review what today’s decision meant for all of these facets.

The discussion was one between people with good intentions and people with good intentions. People who love Fronteers and people who love Fronteers.

My tweet

I tweeted this:

Yesterday I resigned from the @fronteers board after members voted in favour of a proposal that lets some volunteers charge for their work.

This tweet was phrased harsher than I intended. I did not mean any nastiness, but can see that it came across as such. I really should have used different words.

What happened is that people, who were previously volunteers, left the conference team. At the same time they put a proposal forward to Fronteers members, that offered conference organising services through their company. Where I said volunteers would get paid, the nuance is that the company of former volunteers would get paid.

I want to clarify that all of this happened through a fair member consultation in which all members were able to vote. There was no nepotism.

I was planning to leave at some point anyway, as it is almost 10 years ago since I first volunteered for Fronteers (at the first conference). I’ve been involved with most aspects of Fronteers since: more conferences, workshops, marketing, meetups, the board, finances, partnerships, et cetera. The situation brought me to do that a bit earlier and a bit more abrupt.

What happened at the members meeting

Fronteers members voted to hire an external company to take care of the logistics of its conference organisation.

The problem being solved

Fronteers can take a lot of its volunteers’ time. Some volunteers have literally spent 1-3 days a week, for years, working on stuff like the yearly conference. Evenings, weekends, but also lots of day time. Freelancers amongst them had to balance this with their client’s time and had to give up billable time to work on Fronteers tasks. Employees amongst them required lenience from their employers. This has been the case for years and is far from ideal.

It has taken me a lot of time to see the above as a problem, as it all seemed so natural. I also realised that it was in fact a problem that affected me, too. Evenings, weekends, day time. Life/Fronteers balance is important, and it is up to individuals to make sure they make that balance.

The arguments in favour

- The proposed solution was ready to execute as it was well defined, with plenty of room for Fronteers to negotiate whatever boundaries necessary.

- The members who brought the proposal into vote had done years of volunteer work for Fronteers. To hire their company made perfect sense: they had experience specifically with Fronteers Conference, spent years organising it for free and contributed a lot to what it is now.

- They did a fair proposal: their ballpark figures constituted a price that would be hard to get on the market, many commercial conference organisers cost a lot more.

- If Fronteers were to hire a company to help with logistics, that company could be held responsible and accountable for various aspects.

- Fronteers already outsourced tasks to third parties, such as catering, WiFi and flight booking

- Finally, someone recognised The Problem and tried to do something about it.

The arguments against

- The proposed solution only solved The Problem for some members. Others also spent evenings, weekends and day time.

- This would be weird for Fronteers volunteers that have to work together with the supplier (weirder than working with a caterer, hotels or venues).

- I suspected the proposed supplier would be hard to separate from the people behind the company, as they were former conference team members.

- Fronteers Conference is the product of years of volunteer effort. Can anyone ever earn any money from that? (This argument regards the caterers, hotels, travel agents etc as fundamentally different third parties, as they are not ran by former volunteers, which is both snarky to even mention and pretty much the case)

- I suspected this would completely change how Fronteers works and possibly cause volunteers to leave.

One last point is that others in Fronteers history who have also faced The Problem, are not going to be paid for their past efforts (this includes those who made this proposal). But this makes sense: none of these people acted as a separate supplier, and applying the new rules to volunteers retroactively would be overdoing it.

To get around of some of my concerns, I co-signed Arjan’s proposal which asked the board to investigate the intricacies around paying all active Fronteers volunteers (financially, legally, ethically, etc), i.e. those who spend a lot of time on Fronteers. If all active people were paid, there would be less weirdness. Unpaid people could still remain, and could feel happy to do a lot less work.

My personal context

To give you an idea of where I’m coming from, I would like to share some of my Fronteers history (feel free to skip ahead to the next section). After I was approached to volunteer at the first conference in 2008, I continued volunteering for every single conference until 2013. In the first few years I was a ‘runner’, in the last years I joined the actual team. I was given responsibilities like sponsorship, volunteers, marketing, visual design, speaker curation and even had the honour to be the chair in my last year.

I also took on other tasks within Fronteers: I briefly chaired the marketing and workshops teams, and after I joined the board in 2014, I became treasurer in 2015. The last year was one of my heaviest: I helped Fronteers transition to a new bookkeeper, organised the preparation of two sets of accounts (2014 and 2015), restarted the workshops team and organised four workshops, helped organising four meetups and kept in touch with various organisations for our new front-end community support program.

I’ve very much enjoyed (most of) this. I made many friends, had fun, learned loads and met many friendly Fronteers fans who appreciated the stuff Fronteers did for the community. Yet it did cost me a lot of time. Evenings, weekends, day time.

I resigned from the board immediately after the vote. I had spent about a week contemplating doing this in case of a vote in favour of the proposal. The reason? I accept the decision, but assumed the proposal would take time to work out, and foresaw a backlash that would take the board’s attention for a while. I decided that I did not want to spend my free time on dealing with the situation. I was looking forward to spending the last year of my 3 year board term organising workshops, meetups, community support and possibly the new website. The acceptance of both proposals radically changed the board’s priorities, and I could not see myself stay yet ignore that. I saw an early end as the best way to solve my Fronteers/life balance.

What now?

Both the proposal to hire a supplier and the proposal to investigate paying Fronteers volunteers were accepted at the members meeting. The vote happened and this is now the direction in which Fronteers is moving. The board and others (like Peter-Paul Koch) have constructively started thinking about how to carry out the proposals. This will be a complex task, because there are a lot of questions about the details and conditions.

The 2017 conference will be fine too. It’s going to be the tenth year of Fronteers! The idea is that a team of volunteers will be erected to organise the conference, and that they will be in charge of contracting Eventstack (and any details concerning that contract).

Personally, I committed to keep carrying out my treasurer tasks until the end of the year, including making sure the accounts for 2016 are prepared and transferring all I know to my successor. I will also continue chairing workshop team, and hope to organise many more workshops in the new year. After, I hope to get some new hobbies.

Update: from 1 April I have left the workshop team, I am now no longer involved with organising things for Fronteers

Originally posted as Leaving the Fronteers board: what happened on Hidde's blog.

Review: Inclusive Design Patterns

This week Heydon Pickerings’ Inclusive Design Patterns came out. As I was quite fond of his previous work, I insta-bought the ebook version (hard copy will be available from October).

The book does not (only) show you how to write front-end code in an accessible manner, it teaches you how to think like an inclusive designer. That is, a designer that considers the widest range of people possible. Heydon does go into the code involved, but that is mostly in support of the inclusive thinking he advocates.

It’s all about making things work for people

The book shows why creating accessible websites is not a ’bureaucratic box-ticking’ exercise (IDP, 121). It’s not just a matter of slapping on the right ARIA attributes, it is all about envisioning what would give people the best way to experience your site. Designing the best way for people to use your thing. If ARIA helps with that, fine. However, Heydon warns, never fix something with JS and ARIA if it could be done with HTML and CSS.

Inclusive design, says Heydon, has this as its object: ‘the user’s ability to actually get things done’ (IDP, 121; emphasis his). Throughout the book, it becomes apparent that making a product accessible is not a matter of always doing X or always doing Y. You have to always consider (and then test) what works best, has wide browser support and gives the best results.

Inclusive Design Patterns is full of interesting things, like how to use Schema to make search results for your site more accessible, what screen readers voices say and how to tweak that, and giving users feedback on form input with live regions. It contains many real world examples, like filter widgets and ‘Load more’ interactions. Clever ways of making things work. There really is something to be learned for everyone in this book. Highly recommended! (Buy the ebook)

Originally posted as Review: Inclusive Design Patterns on Hidde's blog.

Things I learned at From the Front 2016

This week I visited the 6th From the Front conference in Bologna, which this year was themed The Frontend Guide to Life, The Universe and Everything. It was my second time at the conference, having visited their first in 2012. Great to be back!

Below I share with you my takeaways from two days of From the Front. I have written a summary of each talk, occasionally mixed with personal opinion.

The Frontend Guide to Life, The Universe and Everything

The Frontend Guide to Life, The Universe and Everything

We can develop personally to deal with the enormous amount of change in the 2016 web

Lyza Danger Gardner talked about overchoice, ‘the idea of an overload of choice’. Having worked on the web since the nineties, she already worked on the web when tables were commonly used for layout and CSS was a novelty. Browsers improved very slowly. The complete opposite is now true: browsers take feedback very seriously. New features get added very quickly into the browsers that people use. This also means there is a lot to learn. When Lyza spent 6 weeks in the woods, six weeks without working on web stuff at all, she felt she had to relearn the trade. And this is from someone who has worked on the web for a very long time.

Having the feeling that everyone else is smarter or that it is all just too much and you want to quit the trade altogether, can make individual developers unhappy. “We really want change, yet change is killing us, too”, Lyza said. She explained how she made some personal choices in order to take back responsibility for her own happiness.

Its built-in robustness makes the web great for progressive enhancement

Jeremy Keith shared with us a story of how the web was invented. Its main virtue, he explained, is that it is deliberately dumb: it provides simple mechanisms to transmit packages (TCP/IP), mark up documents (HTML) and declare what they look like (CSS). Beyond these mechanisms, the web does not care. It does not care what you name things, or what protocols you build on top of it. Super powerful, right from the start. It is also designed to be robust; browsers will not throw errors if you forget to close your HTML element or use a CSS property that they do not recognise. Instead, they will parse what they can parse. JavaScript is a bit different, as it will throw errors when you make a syntax error. This difference lets us divide front-end tech in two categories: the resilient and declarative (HTML, CSS) and the fragile and imperative (JavaScript).

Jeremy noted some websites now rely on JavaScript, which is fragile, to display content. He then made a strong argument for progressive enhancement. His strategy is to (1) identify core functionality, (2) build this with the simplest tech and (3) enhance. If you get (1) and (2) right, you can go crazy in step (3) and use tech that does not necessarily have broad browser support, without witholding core functionality from people. Service Workers, WebGL, push notifications, anything! This approach can take more time if you are not used to it, but it is definitely possible, even on large scale corporate websites (some might say they would benefit the most).

We can make non-default things in HTML accessible to more users with ARIA, keyboard support and focus management

Léonie Watson explained how to make our web applications more accessible (slides). The important part is that everything in our web application exposes three things: their accessible name, their role and the state they are in. This is easy for things that already exist in the web platform, like links, buttons and form elements. Browsers already know their names, roles and states. In other words, default HTML elements are already accessible out of of the box.

It gets more complex when we want to use things that don’t exist as such. Tabs, for example. Léonie showed us how to mark up tab links and tab panels in a way that is most usable for users of assistive technologies, and explained how ARIA attributes can help here. She also showed how to build in keyboard support and manage focus.

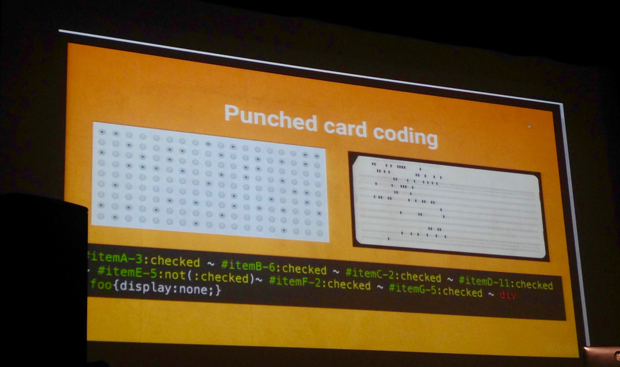

With radio buttons and checkboxes we can use logic to make HTML emails more interactive

Mark Robbins is an expert in interactive email HTML. He showed some perplexing techniques for making emails interactive. The trick: making extensive use of the ‘states’ that can be styled with CSS. Things like :hover, :active and :focus, but also :checked (a lot of that). By including a number of radio buttons / checkboxes (and nested labels for them), the document can have logic that can be targeted from CSS. For more advanced logic, a ‘punched card’ can be coded in radio buttons and allow for even more complex hiding and showing.

Using the above, Mark created galleries, interactive games, live shopping cards that can even update prices (using CSS counters), form validation, analytics that work by fetching background images based on :checked states and 3D views of products utilising CSS animations on 3D transforms. At the end of his talk, Mark revealed that even his slide deck was built as an HTML email: he had been presenting everything from Apple Mail. Mind. Blown. While Mark was talking I wondered about the accessibility of it all, and later I found his company has posted Accessibility in email and Accessibility in email part II.

All problems can be solved with CSS

Sara Soueidan showed us some of the work she had been doing on the upcoming redesign of Smashing Magazine. First, she talked about SVG and when to use or avoid it. She said that ‘not only should the image be a good candidate for SVG, the SVG should also be a good candidate for the image’: too many shadows/gradients/paths might mean a large file size and make an image less suitable for SVG (and more suitable for PNG). She also talked about scalable type: type can scale with the viewport when using vw/vh units, but then the need for minimum and maximum font sizes arises (font-size: calc(16px + 3vw can help here; 16px will work as your minimum size).

Some absolute highlights of Sara’s talk:

- she showed how a seemingly impossible article layout could be done with CSS

- she explained how she made whole blocks with links in them clickable while retaining the focus order she intended

- she talked us through building custom ordered lists with CSS counters

- she showed a method to do better underlines using text-shadow in the same colour as the background-colour.

This talk once more showed how incredibly flexible CSS is if used by smart people: everything is possible.

We should regularly reflect and listen to our gut feeling

Conference organiser Marc Thiele talked about the changes he had made in his life, recently and less recently, and the events in his life that triggered those changes. They lead to many good things, including his first Flashforum conferences years ago, and his current Düsseldorf/Berlin based conferences about the web in general. He explained that it is important to make time to reflect on the past and encourages the audience not to be afraid to make changes.

Apprenticeships can be a great thing for the web

Dan Mall ended the first day with a talk that strongly encouraged us to start an apprenticeship program within our companies. He shared his experiences with doing so in his own company. Apprenticeships encourage the best form of learning, he emphasised. They don’t just teach things you can learn in a school, they also teach people how to be a professional, act with customers and sell their services. They can decrease the gap between the best of our industry and people who have an interest in joining our industry. To take an apprentice does not have to be expensive or time consuming, Dan’s personal experience showed. Averages from 10 apprenticeships his company hosted, show a cost of about $7000 and a time investment of about 36 hours per apprentice (over a period of 9 months).

We can improve perceived performance by reducing passive phase waiting time

In his talk about the psychology of performance, Denys Mishunov said research showed that people who have to wait too long for specific things on your site, may end up disliking your entire brand for it. Reducing this waiting time and improving performance is not just about numbers, it is about experience as well. Denys discussed two phases in waiting, which he referred to as the active phase and the passive phase. Active waiting is waiting while your brain is still busy with other stuff, passive waiting is just waiting. A wait with an idle brain is perceived as a longer wait. Naturally, active waiting is a lot less frustrating, so a way to improve perceived performance is to make the passive phase shorter (even if that makes the active phase longer). In code, Denys explained, this can be done by taking advantage of resource hints (dns-prefetch, preconnect, prefetch, prerender and preload). In interaction design, it can be done by letting people do stuff while they wait, for example adding meta info to a photo that’s currently uploading.

Serving over HTTP/2 may the best thing you can do now to increase your site’s performance

Patrick Hamann explained to us why it would make sense from a performance point of view to start serving your websites over HTTP/2, given that we have already done other performance optimisations. Slow websites are often slow because of latency, and HTTP/2 fixes a large part of that. The major inefficiency of HTTP/1.1 is ‘head of line blocking’. HTTP/2 fixes this with its ‘multiplexing’ approach: bits of data that are called ‘streams’, of which multiple can go over one (!) TCP connection. A stream carries messages that are made up of frames, like its header and its actual data. Frames are binary, as opposed to data sent as plain text in HTTP/1.1. The advantage of that is that they can interleave, the disadvantage is that they are no longer human-readable. Streams can also have weights attached to them, and with HPACK their headers can be stored in referencable IDs so that they don’t need to be endlessly repeated. Special PUSH_PROMISE can inform the browser about resources it is going to send, saving requests.

To start using HTTP/2 you need HTTPS (Let’s Encrypt helps here) and a server that can handle HTTP/2 (many servers can now) and use its features. If you use CDNs, you also need to make sure they can do HTTP/2. Support is really getting there, and that means HTTP/2 is pretty much ready for adoption.

Voice User Interfaces are coming

Ben Sauer talked about user interfaces that are controlled by voice (VUI). Systems like Amazon Echo, Apple’s Siri and Microsoft’s Cortana. These companies are currently all heavily investing in voice technology and computers that are all around you all the time (‘ubiquitous computing’). They are also trying to normalise voice interactions, by showing their tech in social contexts, making it a lot less weird to be talking to your computer. With voice interfaces, Ben explained, apps will become more plain, or possibly invisible. The brand will likely be less invisible, too: if you ask your voice-based assistent what the name of a song is, you won’t go into a branded app interface, and you don’t need to know it uses the Shazam brand for it.

VUI still needs a lot of work, as it is not so good at large amounts of input, dealing with natural breaks in speech and working out fuzzier tasks. And then there is privacy, a huge issue in my opinion: a lot of VUI requires a microphone to be always listening (and this would be great for your ex or the police to listen in, too).

Your design system will thrive when you group modules by function and get their naming right

Alla Kholmatova did not try to convince us to come up with design systems for our sites, as every site already has one (paraphrasing her). A lot of her talk was about how to make it work better, through documentation and cross discipline collaboration. Integral to Alla’s approach is separation by function (not form): you try to figure out which things on your site have the same functional role, and group those together. Naming is incredibly important when working on the design of a site as a team: once something has a name and can be found under that name in a pattern library, it becomes a thing, it ‘comes into existence’ .

Alla shared five tips with us:

- Give your modules names that relate to the system, not to a specific page. Functional names (related to what something does) usually work better.

- You’ll likely have some modules that are generic and others that are specific. Let their naming reflect this. It’s okay if a specific thing is at some point changed to be a generic thing or vice versa.

- Name things collaboratively and make a point of always referring to the things by the names you’ve given them. This takes effort, but it is very helpful.

- Use names with personality, as they tend to stick better. You can use metaphors borrowed from other industries, or even from films. If names are not remembered by team members, you risk duplicate modules being created. Good names inspire other names, Alla said, and before you know it a family of names starts to grow.

- If it’s hard to come up with a name for a module, this may be a sign that there’s something not right about the module, you may need to go back to the drawing board.

Another interesting thing Alla shared is that at Future Learn, spacing in modules is part of their design system. They distinguish between types of modules: spacious, regular and ‘cosy’.

Finally, Alla recommended reading How to make sense of any mess by Abby Covert, and looking at the Visual Loudness Scale that Tom Osborne wrote about.

CSS Modules is a JS powered CSS pipeline that addresses concerns with the CSS language

Hugo Giraudel explained what CSS Modules are: a JS powered CSS pipeline that gives CSS namespacing, amongst other things. “CSS is broken”, Hugo said, because it has a global namespace, does not come with dependency management and has no mechanism to share configurations. CSS Modules lets you have all three, and can be plugged into various JS pipelines. Definitely a fascinating concept! It’s easiest to set up with Webpack, but can be used in Browserify or even Gulp. Hugo made a solid case for CSS Modules, however I personally strongly disagree with his premise: that CSS is broken and needs fixing. I admit CSS does not check all boxes that programming languages do, but I think that is because CSS is not a programming language (probably something for another blogpost).

Visual regression testing is most helpful when used on isolated components

Varya Stepanova showed us her approach to visual regression testing, the process of keeping track of visual differences between versions of your application. Instead of automatically testing whole pages, Varya said it is a lot more helpful to test isolated components. She demoed the Gulp plugin she built to do isolated visual regression testing. It uses PhantomJS to take screenshots (see on GitHub). Varya also explained the business value of having a component library with automated visual regression tests on each component: it makes the UI more stable and ultimately lets teams work faster.

If we want to do the good thing, we need to design features on websites with empathy

The last talk of day 2 was by Beth Dean. She shared her fascinating employment history with us, and explained how all these different things she did made her realise the importance of considering emotions in web design. “A lot of people live in a world that is not designed for them”, she said. Ill-considered design choices can give individual users of your site a terrible experience, for example when you send Mother’s Day marketing to someone who’s mother recently passed away. Part of the solution to this problem is to ensure that design teams are very diverse (in age, gender, ethnicity, etc). In addition, it is important for designers to be aware of any privilege they may have, and to have an attitude of empathy towards users.

Originally posted as Things I learned at From the Front 2016 on Hidde's blog.