Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

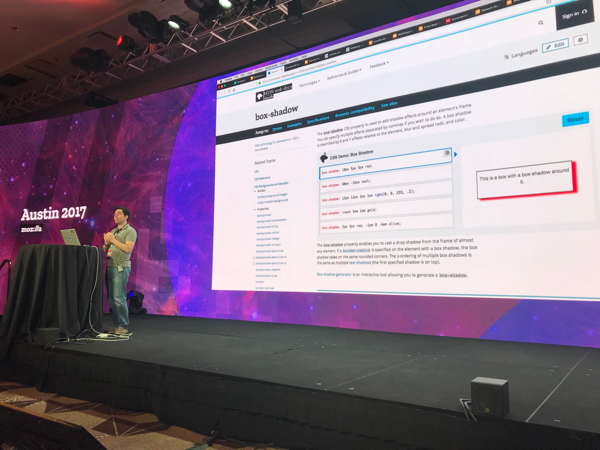

#yallhands

Last week I was at Mozilla’s All Hands in Austin, Texas (hence the hashtag). All Hands is an all company event where the people who work for Mozilla come together in one city. Staff, but also prominent volunteers, contributors and community leaders. It’s all about sharing experiences and meeting people.

It was my first All Hands, and the first time for me to meet any of the people I have worked with for the past six-ish weeks. The week went by faster than I could have imagined. I had been warned for this. Beforehand, I had heard great things about the event, but, wow, it was incredible! So many people met, so many productive sessions had, so many stickers acquired and various American foods tried.

Throughout the week I was in many meetings in various settings with colleagues from Open Innovation, as well as with the IT department whom we collaborate with for identity and access management work (the IAM project). We made plans, shared ideas, talked about planning and discussed our processes. Tons of things that are easier to do in person. For me personally, it was great to learn that and how our daily work fits in the broader Open Innovation and Mozilla goals.

Below, I’ve provided a couple of links to projects and ideas for y’all.

Plenaries

A plenary session opened the week, featuring most of the people leading Mozilla, including CEO Chris Beard and Executive Chairwoman Mitchell Baker. There was a lot to celebrate about 2017 for Mozilla. The launch of Firefox Quantum which had been years in the making, projects like Common Voice that want to facilitate machine learning of voices for all, the programming language Rust that gained a lot of momentum and an MDN that is supported by all major browser vendors. All these initiatives are means to support Mozilla’s mission: to have a web that puts people first and empowers, rather than one that facilitates harassment, walled gardens, fake news and digital exclusion. Sillicon Valley isn’t necessarily society’s friend. These are things that need fixing. Katharina Borchert explained that, as these fixes need an answer that goes beyond technology, Mozilla has set up a policy team. Mozilla focuses on five issues in particular.

![]() “Even mainstream media are noticing”

“Even mainstream media are noticing”

Throughout the week I learned about lots of different projects that clearly work towards this mission. I picked up lots of dots and it was great to see how well they all connected. For example, later in the day, I attended the Mozilla Foundation’s plenary session. Some of the Mozilla fellows presented their work on things like Net Neutrality, the Internet Health Report and privacy. All things that help fix what’s currently broken on the web.

Electives

On Wednesday afternoon I attend various electives: sessions open to anyone, focused on a specific subject. There was a lot of good stuff to choose from, I ended up going to the ones about the Photon Design System, WHATWG and a design system approach to Mozilla’s websites.

Photon Design System

Photon is the design system used by the people who build Firefox. It was created because browser engineers and designers wanted it, to make it easier to have the same look and feel across the browser, on all the platforms it works on. Currently it is ‘just’ a website that documents the design choices, but the team are looking in turning the style guide into a living style guide. In a fun post-it note exercise we looked at the pros and cons of Design Tokens. They are design decisions abstracted into JSON files, so that they can be reused. In CSS or Sass, but also in design software like Sketch. This setup can create an application agnostic approach to documenting design, because the tokens are easily shareable between platforms and people.

It was fun to think about Design Tokens

It was fun to think about Design Tokens

WHATWG

At the session of standards community WHATWG, I learned about their recent changes to dealing with intellectual property rights and what they mean for contributing. The new IPR agreement and way of working was developed together with all major browser vendors: Apple, Google, Microsoft and Mozilla. They all have representatives in the Steering Group. Spec contributors of all of those companies now contribute to the Living Standard/WHATWG-version of specs like HTML, rather than the W3C version (as GitHub activity shows). The session was quite positive and people seemed eager to work together with others including W3C, and minimise confusion for developers and browser implementors.

From wagile to agile with mozilla.org

Craig Cook, front-end developer at mozilla.org held an elective about design systems. Mozilla has hundreds of websites, some quite old and some brand new. Many of those have been developed in a process that started as agile but quickly became waterfall, something he ironically referred to as wagile. Design systems can help here, because if multiple sites make use of one design system, it is only that system that needs updating rather than individual sites. That would really offer the flexibility in process that wagile lacked. Other than process it will likely improve user experience, as human brains are good at pattern recognition, having reusable patterns leverages that. As someone who works on some Mozilla sites now and in 2018, I look forward to seeing the design system flourish.

Lightning talks

I also attended a number of lightning talks. Some facts from those:

- you can have sourcemaps for Web Assembly (wasm) compiled Rust code in the browser, which can make wasm debugging as straightforward as JavaScript debugging

- user testing showed that action-oriented users of MDN are better served with a live preview CSS editor.

- the RNNoise project teaches computers to reduce noise with recurrent neural networks

- incremental Rust compilation is coming, which will make things a lot faster

- Web of Things is a horizontal stack and open source approach to Internet of Things, for which Mozilla submitted the Web Things API spec

- there is talk about a Rust-powered version of Ember

- Common Voice aims to create an open source data set that can be used by anyony who wants to teach machines about recognising voices; it has collected as much as 500 hours worth of speech data

CSS editor in MDN

CSS editor in MDN

This week has given me a lot of energy, despite the inevitable shortage of sleep. It has been a lot of fun to be part of this. It was refreshing to meet this super global community, with different countries and cultures represented. I am looking forward to Q1 of 2018, and the work that lies ahead. Because executing things is even more fun than planning them!

Originally posted as #yallhands on Hidde's blog.

What to use Grid Layout for? Some ideas.

If you have learned how to use Grid Layout, you might wonder what to use it for. In this post, I will give some use cases where I think Grid will excel.

In the last two weeks I gave two workshops on CSS layout techniques. Heavily inspired by Jen Simmons’s remarkable Grid Layout experiments, I picked three posters that Wim Crouwel designed. Crouwel is a graphic designer that has been making use of grids for a long time, including for all the characters in his New Alphabet typeface. His work is iconic and I was quite excited to see some of it could easily be built for the web using CSS Grid Layout.

I liked how working on non-real world examples played out, as the focus was really on applying all those different properties, rather than writing production-ready code. Old posters are great to try this stuff out on.

After the workshop, Michael asked me what we can use Grid Layout for in the real world, if not for recreating iconic posters from the history of graphic design. I talked to others about this and found various people weren’t sure what to use Grid Layout for in actual websites for clients.

I’m sure we can use it for a lot more than recreating old posters. There definitely are good use cases, so I thought I would make a list of where I believe Grid can help us create cool stuff.

Use cases

To show what’s on offer

Grids are perfect for showcasing things, inspire visitors, communicate to them what kind of stuff we have on offer, in a very broad way.

We can do these things with old-school layout methods. However, using CSS Grids they can look more exciting, it is trivial to make some things appear more prominently than others and it is easier to have the browser deal cleverly and responsively with content differences.

- For an online supermarket: a listing of products with prices, reduced prices, product names

- For a library: a page with reviews of the five books that have recently come out and have great reviews.

- For an airport: an overview of the tax-free shopping available

- For a railway company: a selection of exciting holiday destinations, weekends away, day trips

These are all listing pages that want to inspire people to find stuff, whether it be groceries or books. They can benefit from things only Grid offers.

For one-pagers with a lot of different sections

Many front-end developers will have had to code them if they worked on marketing sites in the past five years: one-page websites in which every section is quite different. They often have lively designs. Lots of differences between sections makes it hard to code systematically.

With Grid Layout you can keep the markup of these sections nice and plain and choose a sensible and consistent source order, while still allowing yourself to go wild creatively on each section.

To display a schedule

We can use grids to display information about what’s happening at a given event, conference. Note that proper markup will be extra important here, as for accessibility reasons we want to make sure the content makes sense without its Grid Layout.

For embedded layouts that fill the entire screen

If you’re building an interface that is supposed to go full screen on some physical product, Grid Layout might be quite a helpful way to distribute space.

A while ago, I built an interface for a Dutch department store that would be used by the cashier when you pay. It had things like your products on and stuff about loyalty card usage. This kind of interface runs full screen in some sort of embedded browser.

Some use cases:

- your digital tv interface

- the self-check-in screen in an airport

- the screen you see when you return books at the library

- a screen that shows information on the next train

With a grid that is based on viewport units (vw/vh) and/or fractions, space distribution and alignment may get a lot easier. (I have to admit, in my case the screen ran a browser that was almost identical to IE7 and the system’s output gave me only tables to work with).

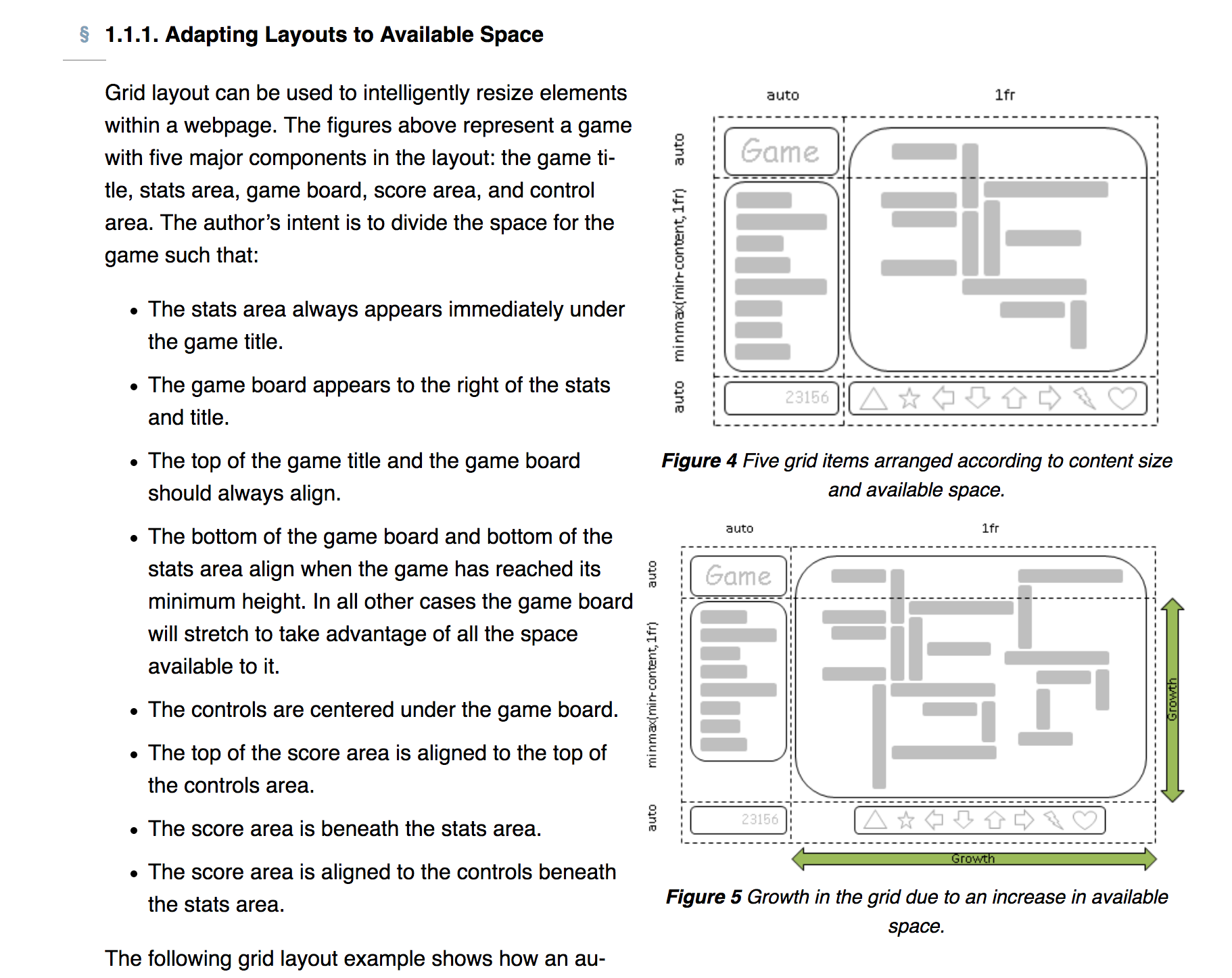

The Grid Layout Spec has an example of a game that always fits on your screen. The required markup/CSS is ridiculously little.

The Grid Layout Spec has an example of a game that always fits on your screen. The required markup/CSS is ridiculously little.

An example

Imagine we have a grid with cards in it for a supermarket’s weekly offers.

All offers take one spot in the grid using autoplacement. However, some offers are more prominent, and we could make them use two rows:

.offer {

// regular offer code goes her

}

.offer--prominent {

grid-row: span 2;

}I don’t work at a supermarket’s marketing department, so my knowledge of its possible marketing strategies is lacking, but maybe there are other offers. Perhaps one that will expire after this week. This is people’s last chance, so we make it use three columns and two rows.

.offer--last-chance {

grid-row: span 2;

grid-column: span 3;

}This is stuff that is trivial in a Grid Layout and impossible to do so easily and flexibly using traditional methods like display: inline-block;. For those of us who have used floats, inline-block and even tables to do lay-out, using Grid Layout may be a bit of a mental shift. I suspect this applies a lot less to people who learn CSS layout today, as they will start in a reality where the new stuff already exists.

Conclusion

There are plenty of uses cases where Grid Layout would be a sensible implementation choice. I have listed some examples above, but I am sure there are more — please leave a comment or tweet if you have found other ideas.

Originally posted as What to use Grid Layout for? Some ideas. on Hidde's blog.

The web is ready for great graphic design

There was a time when front-end developers would frown upon (former) print designers that designed for the web. At their usage of ‘perfect’ yet unrealistic content, and their creative ideas that were impossible to build with web tech. If this frowning since has scared print designers away from web design, I hope that they return in 2018. New CSS possibilities are ending the unrealistic content problem and the generic layout problem. It’s a great time to build layouts in CSS!

Problems solved

The unrealistic content problem

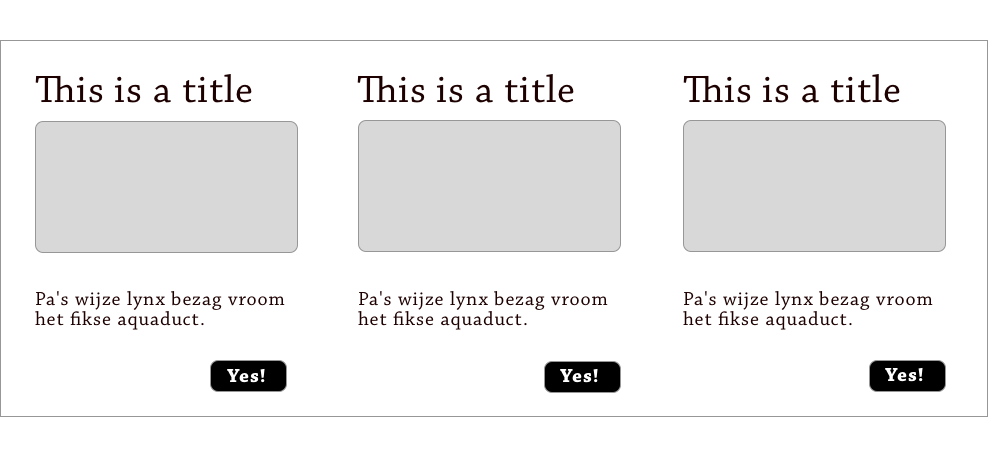

It is now not as common, but I’ve still seen it happen in the past few years. A designer presents a design. The content lines up beautifully, because it is picked to fit perfectly. Headlines that only ever need one line, that sort of thing. It can result in beautiful and balanced visual design. But it doesn’t take many years of front-end experience to know that such designs risk breakage as soon as the template is hooked up to a CMS. The content is updated, and boom, it no longer fits. With new or real content, either the design loses some of its tidiness, or the CMS is set up to force character constraints on content. That leaves the design tidy, but the content inflexible.

When content for one of the blocks changes, it will not be trivial to line up

When content for one of the blocks changes, it will not be trivial to line up

Most of these problems have to do with keeping things the same height and doing advanced alignment. These are both requirements that are super easy to do on paper and in design software. Easy to do when making a static comp. I guess. But CSS never had tools for doing this flexibly and with unknown content (table layout excepted).

In the CSS Layout workshop I ran for Fronteers last week, I tried to emphasise that recent updates to CSS mean that the above is soon (or now, actually) no longer an issue. CSS Grid Layout (and flexbox, to some extent) will let us have our cake and eat it, too. We can make things line up or be the same height in a whim, regardless of content. We get flexible units like ch and fr that make it easier to line things up in a way that was always quite sensible, but never quite feasible. Unrealistic content, then, is less of a problem, as we have actual alignment options, rather than CSS trickery.

The defensive design problem

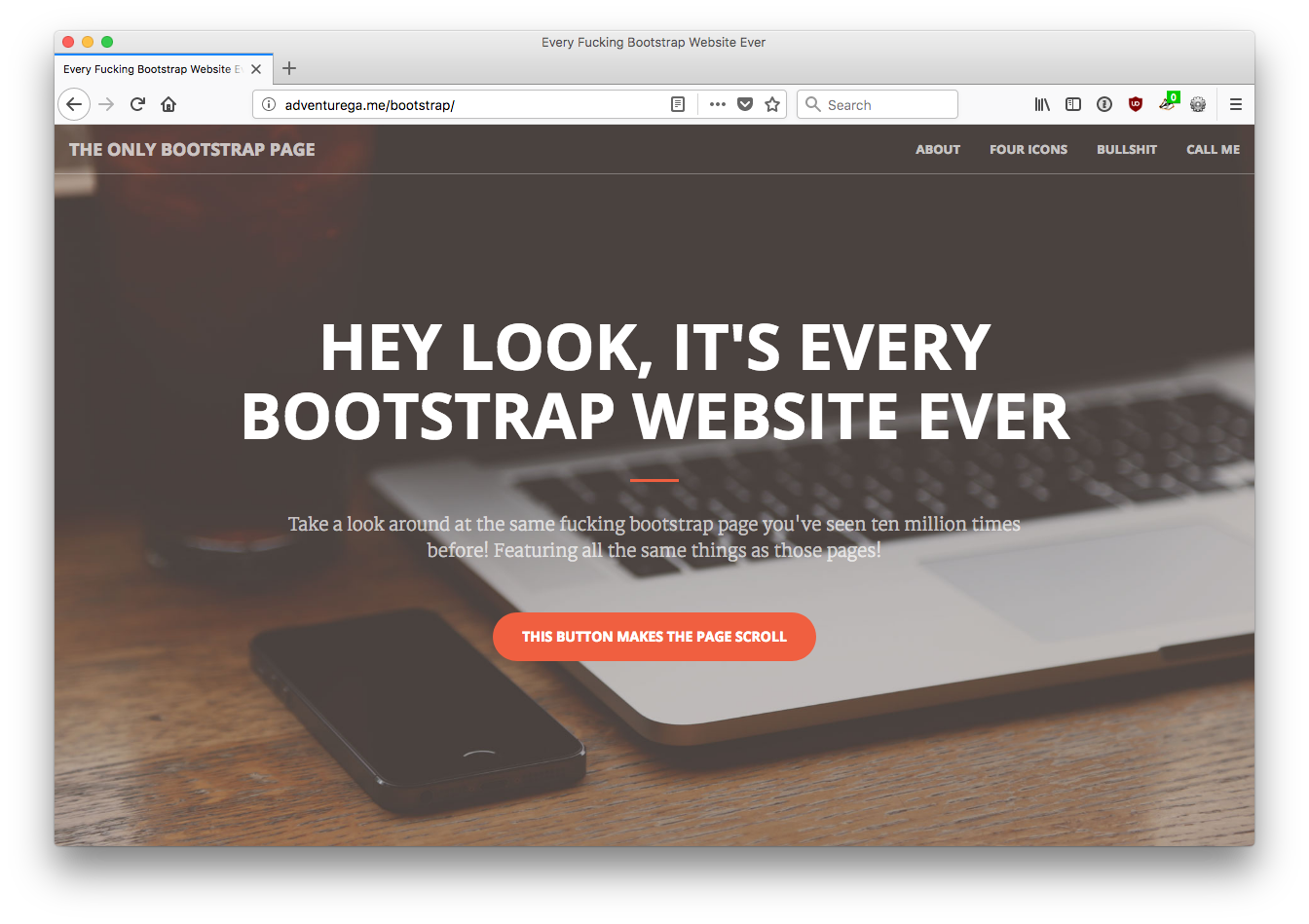

Every so often, contracting for agencies, the designer of a new website would come to me and ask ‘What kind of layout framework are you using? What’s the grid, are we doing Bootstrap or Foundation?’ Sometimes the agency had already listed one of these as a requirement during recruitment. I often found that the in-house developers were used to dictating these kinds of things. Lucky bastards! The reason is probably practical: when producing website after website, it makes sense for a team to start optimising things and have one way of doing grids. When working with contractors, it is useful if that one way is a broadly used open source framework. But it also seems oddly out of order: it can be a lot like solving problems before you have them.

The thing with CSS layout frameworks is that there is a fixed amount of stuff they can do. The things that are generic enough to make it into the framework. They speed up things, and are super helpful for prototyping and even creating production sites. But they don’t just create a generic way of working. They also create a generic look of websites. I’m not the first to conclude that.

Defensively designed websites tend to look the same

Defensively designed websites tend to look the same

Web design with CSS frameworks in mind is, I think, to design defensively. The approach gives a lot of certainty about whether something can be built, which leads to happiness throughout the team, including product owners.

2018 may be the year that we no longer need to design defensively. Because Grid Layout is here. By ‘here’, I mean in our users’ browsers. In The Netherlands, on average 85% of users use browsers with full or partial (IE11) Grid Layout support.

With CSS Grid Layout, we no longer need frameworks, CSS now is the framework. This is great, we can now solve problems when we have them. With something that is a web standard.

New challenges

There are new challenges, too. The stuff Grid (and flexbox, to some extent) does, can be unexpected to those who have not mastered the spec. That’s probably most of us. They have documented Grid’s behaviour exceptionally well there, but it is perhaps only in real life designs that we will get a feeling of how it all works. For instance, what autoplacement does and how to leverage features like minmax and min-content to get our designs exactly how we want them.

Letting it go

Grid Layout has a lot of ‘leave it to the browser’ kinds of settings. Rather than ‘make this thing 400px wide’, you set things like ‘make it fit roughly between 40 and 60 characters’. More than ever, it is clear that CSS isn’t about exactly specifying what we want.

John Allsopp famously discussed this in A Dao of Web Design, over 17 years ago. He talks about “to suggest the appearance of a page, not to control the appearance of a page”. For this, he says we need to let “go of control”:

It is the nature of the web to be flexible, and it should be our role as designers and developers to embrace this flexibility, and produce pages which, by being flexible, are accessible to all. The journey begins by letting go of control, and becoming flexible.

(Emphasis mine).

“Letting go of control” is about letting the browser decide based on our hints. Browsers are good at this. They have all the knowledge: what device they’re running on, how much space is available, what fonts are available, which settings the user has set, et cetera. But it isn’t necessarily something all web teams like to do, I found.

Communicating flexibility

Even if we as CSS developers have mastered the spec, we still need to be able to communicate and explain the consequences of our code to designers, product owners and stakeholders. This is key. It requires us to explain stuff to the rest of our team. Results that struck us as unexpected will likely strike them even more.

Historically, we’ve seen a lot of website owners like the idea of their websites looking exactly the same everywhere. But it is now clear to most that this is no longer feasible. The case for flexibility has become lots stronger in our current multi-device reality. The internet is on so many devices: fridges, cars and watches with browsers now exist. This reality has powered the responsive design argument, and think it can power the flexible layout argument, too.

Conclusion

So, yes, the web is ready for great graphic design. The flexibility it was invented with has recently flourished with the surge of responsive web design. We now have CSS layout methods that let us embrace flexibility and they have good browser support. Cool experiments are done with CSS Grid Layout.

The case for using flexible layout methods will require clear communication between front-end developers and the rest of the team, as well as in-depth knowledge of these new lay-out tools. But I think we can do this. We’ve done it before with responsive web design, and we can do it again!

Originally posted as The web is ready for great graphic design on Hidde's blog.

New challenges

This month is my last at Wigo4IT, and I’m excited to start new projects at Mozilla and the Dutch Ministry of Internal Affairs.

Leaving Wigo4IT

For years, I’ve wanted to work on front-end code for the public sector, inspired by the awesome user-centered design work that the Government Digital Service (GDS) have done in the UK. While I lived there, I wasn’t in London, the closest I got to the GDS was working for Nomensa and sitting near a team that did a GDS project.

Back in the Netherlands, I was quite excited when Informaat, a user experience agency, approached me and asked me for a project they did for local government. Long story short: I spent a bit of last year and a large part of this year contracting for them at Wigo4IT. Wigo4IT is a cooperation of the four largest Dutch municipalities, who work together on software related to social welfare.

I worked on a portal where people can apply for income support. The role of our front-end team was to build a responsive component library that can be used to create WCAG 2.0 compliant pages. The project was full of challenges related to web forms, front-end pattern libraries and theming. It was also a lot of fun to advocate for accessibility as part of the project, and my first time to have the JAWS screen reader software available to test on. I learned a lot about differences between the public and private sector, on many levels.

New challenges

Mozilla

As of next month, I will join Mozilla for a couple of months as a freelance front-end developer. I will be working for the Participation Systems team, the team that has as its goal to make it easier and more effective to contribute to Mozilla projects for all. I am incredibly excited (and slightly scared) about getting the chance to work with some brilliant minds.

Government

I have also recently started to work on two projects for the Dutch Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations together with Atticus: one to apply a redesign to a set of government data related websites, and another one related to accessibility guidelines conformance statements. I love this, because this is the Ministry where a lot of the official Dutch accessibility information and guidelines are published.

CSS Workshops

Lastly, this year I will also be giving my first workshop (organised by Fronteers). Two times, in fact. It’s going to be about modern CSS Layout, including flexbox and CSS Grid Layout. I hope I’ll convince the attendees that those who haven’t yet can now safely abandon Bootstrap for layout, and that we can have lots of fun exploring and using new layout-related properties and thinking.

Originally posted as New challenges on Hidde's blog.

Web Components as compositions of native elements

I wrote a post about Web Components about two years ago, wondering what kind we would need, if any. More companies have recently started adopting web components. I’m starting to get more excited about them, and think they can be very helpful to encapsulate compositions of elements.

Please note: this isn’t a recommendation for ‘switching to Web Components’, at the time of writing browser support is weak and the ‘components without libraries’ is not reality yet. I’m only exploring the theoretical argument.

We have all the elements we need…

At university, I learned something about Conway’s Game of Life: it can do super complex things with only four simple rules. It has been used to implement things as spectacular as Boolean logic, a clock and a Turing Machine. Similarly, I have always thought the small set of existing HTML tags is enough to build interfaces suitable for anything. From your local grocer to rocket science (for most websites, with some exceptions). We have all the elements we need.

Glider Gun in Game of Life (source)

Glider Gun in Game of Life (source)

To have the capability of creating one’s own elements seemed like fun to me, but unnecessarily complicated. At first sight, it seemed puzzling to me: how many companies are there with the resources to implement Web Components and implement them well (fast, usable and accessible)? Two problems still stand out to me: the need for polyfilling and the fact that going custom means having to provide custom usability and accessibility.

Web Components require polyfilling

To get Web Components working in most browsers, we need to use some sort of polyfill or framework. This puts our problems on users. Maybe they don’t have a fantastic connection or a brand new device. To put it bluntly, they might now experience issues they would not have had to experience if it weren’t for our custom element usage.

Custom makes usability and accessibility harder

Custom elements are custom, so browsers and device don’t ‘know’ what they are for. This means:

- they can’t provide a perfect UI that seamlessly matches the platform (as they do for native elements like

select), which could result in reduced usability - they can’t give assistive technology information about semantics, which could result in reduced accessibility

When the (Shadow) elements inside a web component are native elements, part of this problem goes away, as for those native elements, browsers would likely have perfect UIs and good exposure to assistive technologies.

…but we don’t have all the compositions of elements

Maybe providing new “primitive” HTML elements isn’t the point of Web Components. Although the basic building blocks are there, we often combine basic elements. We combine them to create our own things, our own components, patterns, modules or widgets. We may have all the required elements, we don’t have all the required compositions of elements.

Components are often that: compositions of existing elements, complemented with JavaScript and CSS to make a New Thing. The question is: do we want to encapsulate our New Things, so that they are actual, separate things?

We do this without Web Components, too. In front-end pattern libraries, each pattern often has its own folder, its own CSS file and its own scripts. In React or Vue, developers often blend markup, style and behaviour together in one piece of JavaScript.

A web standards way to compositions of elements

In recent years, the web standard gods have worked on lots of new stuff that allow developers to have more access to and influence on the web platform. And more control. Numerous new APIs have been released to give developers access to stuff that only the OS could access, like location and Bluetooth, and to stuff that only browsers could access, like stylesheets and the network. Getting access to the set of elements that exist, and being able to extend that, makes sense in that bigger picture.

Web Components provide a component model to web standards, so that we can stop using complex tools. Yup, less or no external tooling is part of the argument for web components.

With components that are part of web standards, we need less reliance on frameworks, says Alex Russell in his post Bedrock:

We observed that most of what the current libraries and frameworks are doing is just trying to create their own “widgets” and that most of these new UI controls had a semantic they’d like to describe in a pretty high-level way, an implementation for drawing the current state, and the need to parent other widgets or live in a hierarchy of widgets.

In that 2012 (!) article, he observes that creating widgets becomes the core of what modern web development looks like:

Let that picture sink in: at 180KB of JS on average, script isn’t some helper that gives meaning to pages in the breech, it is the meaning of the page. Dress it up all you like, but that’s where this is going.

So, creation of components, widgets, modules, reusable patterns for user interfaces on the web is commonplace — most web teams do it in some way or another. Frameworks provide ways to do this, but Web Components provide a standardised way to do this. See also: Web Components, the long way.

The bright side

I think the decision to go all Web Components shouldn’t be taken lightly, as many organisations may not have the problems they solve, but there are definitely upsides to them. The future for web components is looking quite bright.

Accessibility

Native elements do a great job at having accessibility built in, i.e. if you use a select you can be quite sure most of your users will be able to select stuff with them, even if they use assistive technologies to access your site, even if they have colour blindness. At the point of usage, you don’t need to worry (much) about how accessible it will be.

If you build your own component now, you will likely use some JavaScript to make accessibility provisions. There’s some risk they get lost when being copy/pasted. With Web Components, those provisions are not in the markup, they are an integral part of the component. They will be there every time you use the component’s terse syntax.

Even better, if the Accessibility Object Model becomes a thing in browsers and Web Components are better implemented, we can set accessibility properties and states directly in JavaScript.

Real encapsulation

With custom elements, you can have scope in HTML and CSS, not just in JavaScript.

IMHO, this is a solution for a problem that is not a problem, but I realise people disagree about this. The advantage of this solution is that you never need to worry about where you use a component, as it will have exactly the styles you’ve applied to it. Personally, I will probably still take advantage of CSS’s cascade.

Conclusion

And that’s what I’d like to end this with: the pre web component web is not going to go anywhere. If your website is not extremely complicated, it still makes lots of sense to just write HTML, CSS and JavaScript, keep things simple and stay away from custom elements and Shadow DOM. Peruse that cascade, do some simple DOM scripting, leverage all that built-in usability and accessibility, and be done with it.

If you have quite a complex codebase that is componentised through a framework like React, it would make sense to look at Web Components, the web standards way to build encapsulated components. In the future, when they are supported across the board. That isn’t the case at this time, so for now, they are still just theoretical awesomeness.

Update 24 October: removed parts that suggested I was recommending Web Component usage today; added a note at the top to clarify.

Originally posted as Web Components as compositions of native elements on Hidde's blog.