Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Review: New Frontiers in Web Design

Last week I had the chance to read New Frontiers in Web Design, the latest in the series of Smashing Books. It just came out and is full of interesting knowledge for people who work on the web in 2018. From CSS custom properties to advanced service workers to bringing personality back to the web.

What’s it about?

Let’s dive right into it. The book consists of 10 chapters, all about different subjects.

Design systems

No elephants in the room were avoided in this chapter about design systems. I loved reading what Laura Elizabeth said about the idea some have of design systems: that they are somehow quite trivial. Creating, promoting and maintaining design systems isn’t simple, and Laura brilliantly shows this. The list of questions to answer for management is very useful.

Accessibility in SPAs

Marcy Sutton writes about the accessibility of Single Page Applications. She shows common pitfalls and how to avoid them. Marcy also goes into managing focus, focusless announcements and when to use which. Later in the chapter she explains how to do automated tests and what they can test for.

Grid Layout in production

In this chapter, Rachel Andrew talks about Grid Layout in the real world. She explains most if not all of the cool things Grids let you do, and explains what one can do about fallbacks using Grid Layout’s built-in scenarios (‘new layout knows about old layout’).

Custom Properties in CSS

Mike Riethmuller contributed a chapter about Custom Properties. I learned various things, like that the var() function takes a fallback value, and that you could use calc() to give unitless custom property values a unit. His examples of writing way fewer CSS rules, by updating values, not which property is being used, are an invitation to go and use this stuff now.

Service Workers

Lyza D. Gardner’s chapter about Advanced Service Workers is great: it is advanced, but explains basic concepts, too. That made it easier to follow along. It reminds of how hard caching can be, and contains some nifty tricks, like giving your Service Worker an ID, that you can use when cleaning out old caches. The chapter also does a great job explaining push notifications and background sync.

Loading resources

‘Loading resources on the web is hard’, concludes Yoav Weiss in his chapter about loading our websites faster. He talks about how websites load and discusses a wide variety of strategies to optimise loading. Both old school classics and fancy new features. One interesting reminder early in this chapter is that HTML is progressive, which makes it load faster than anything as browsers can start processing it when only part of it was downloaded.

Designing conversations

Adrian Zumbrunnen explains what’s important when designing a bot to talk to, and behaving human-like is one of those things, he says. It made me think about how human customer service often offers a robot-like experience, in that their agents strictly stick to their scripts. If we design conversations with bots to be more human, will all conversations end up being very similar?

Chatbots and virtual assistents

Continuing from designing conversations, the next chapter is about engineering them. Greg Nudelman talks about creating plugins for voice assistants as well as standalone bots. As an engineer, I found it a fascinating insight in how this stuff works. As a citizen slash consumer, I would dislike any services that replace their friendly and smart humans with statistical analysis. That may be just me.

Cross reality

Cross reality is the umbrella term for virtual, augmented and mixed reality. In this chapter Ada Rose Cannon explains how to create scenes in browsers, using web standards and some libraries that abstract them. She also goes into improving rendering performance and there’s a useful list of things she wished she had known when she began.

Making it more personal

The last chapter in the book is written by Mr Smashing himself. Vitaly Friedman tells us all about how to put more personality into our work. Earlier this year, I saw him talk about the same at ICONS in Amsterdam. Vitaly encourages us all to create more interesting things. The theme resonates a lot with me. Yes, we need more things that are visually interesting and different. We also need more things that have well considered UI patterns, that ‘exceed expectations’, as Vitaly writes.

My thoughts

Reading this book feels a bit like going to a good conference. There is lots of variety, plenty to learn and you get away with stuff to try out on your project when you get back to work.

There is also lots of variety within each chapter. I felt some chapters covered too much, they could have been more concise. The upside is that you get a lot of content for your money, so there’s that.

One other thing that could be improved is the way references work: footnotes contain just (shortened) URLs, which obfuscates their original address. It may be just me, but I like seeing the name of the author and the name of the post/page being cited, to connect dots quicker.

If a majority of the covered subjects piques your interest, don’t hesitate to buy Smashing Book #6. There will be plenty of new things to learn. Regarding the physical book: I have not seen it yet, but going by the tweets, the hardcover edition is beautiful, so that is one to consider.

Originally posted as Review: New Frontiers in Web Design on Hidde's blog.

#HackOnMDN

This weekend I joined a bunch of web developers, tech writers, web standards lovegods and other friendly folks in London, to work on accessibility documentation for MDN, Mozilla’s platform for learning about web development.

I had a brilliant time, meeting familiar faces from social media IRL and catching up with others. Not only did I learn lots about nails and stools (thanks Seren and Estelle), it was also great to be amongst like-minded people to overhear deeply technical accessibility discussions between people who already wrote about accessibility when I wasn’t even born yet.

Photo: Bruce Lawson, with a hipster filter added, as we were in Shoreditch

Photo: Bruce Lawson, with a hipster filter added, as we were in Shoreditch

On the first day we got to know each other and picked projects to work on. While others looked at adding screenreader compatibility data and documenting WAI-ARIA better, I teamed up with Seren, Eva and Glenda to improve and add accessibility information on MDN pages that were about non-accessibility topics.

What I liked about that particular project, is that it exposes accessibility knowledge to people who are not necessarily looking for it. If you want to know how order works in CSS, you get some information about how it affects screenreader users for free. I’m optimistic. I believe most developers will do the right thing for their users. As long as they have the information on what the right thing looks like in code, design, strategy, testing, et cetera.

After lunch a lot of us gave lightning talks! Eva talked about the problems of automatically translating content and making technical videos available with captions, and Michiel did a great TED-style talk on when to use ARIA. It was just one slide.

Although MDN is a developer network, there are pages for many others. So on the second day I worked on revamping the page Accessibility information for UI/UX designers. It was fairly outdated, so it felt sensible to replace it with more hands-on advice.

On the last day I continued work on that page and did a PR to improve icon accessibility. I also gave a short lightning talk entitled “Making password managers play ball with your login form”, which is also a blog post on this site.

Photo: Bruce Lawson

Photo: Bruce Lawson

Others in the room did great work on getting screen reader compatibility data onto MDN, adding ARIA reference pages, cleaning up docs, modernising Spanish content, updating the WCAG reference with 2.1 content and improving MDN’s tooltips. There were also very informative lightning talks about focus styles, display properties and semantics, WCAG 2.1 and beyond (Silver) and accessible syntax highlighting.

It’s been a great three days. I’ve thoroughly enjoyed both doing contributions to MDN, as well as meeting and learning from like-minded people. And I’m proud we got so much done!

Originally posted as #HackOnMDN on Hidde's blog.

Overlapping skills in front-end development

Last week a poll about CSS did the rounds with a question about the cascade. It got me thinking about CSS and overlapping skills in front-end development.

Is the cascade more complex than other concepts?

The question was, given two class selectors applied to two elements which had the order of classes as their only difference, what they would look like. Many respondents got it wrong. CSS nerds replied that the question was fairly basic, JS nerds replied CSS is shit. Ok, that was likely a troll. There were also sentiments like ‘you don’t get web development if you don’t understand the cascade’ or ‘you don’t get web development if you do like doing CSS’. Oh oh, social media… why am I on it?

Before continuing, I do want to defend CSS. It is a pretty smart and well-considered language. It is not a programming language by design. Concepts like the cascade are complex, but they aid the simplicity of the language, which was an important design principle.

Admittedly, it takes time to grasp such concepts before you can take full advantage of them. But isn’t that the case for most concepts in web development? Component lifecycle hooks, accessibility trees, dockerisation, OIDC, Lambda functions, writing mode agnostic (logical) properties, Content-Security Policies, DNS entries, git rebase… they all make complex-to-understand things available in simple-to-use ways. About many of these, I was frustated at first, but happy and excited ever after.

CSS may (seem to) miss some of the determinism, scoping and typing that many programmming languages offer, but I believe it is precisely the lack of those sorts of things that makes it extremely accessible to learn and use. It is by design that you can’t know what you HTML will look like. And we’re able to use JavaScript to add such features ourselves, if our codebase or team is of a size that requires them.

Overlapping skills

As people who make websites, we all specialise in different things. They often overlap. Some of us are markup nerds, server side rendering nerds, svg nerds, sysadmin nerds, security nerds, network nerds, Grid Layout nerds, webfonts nerds… most are a combination of many of these things. Some of us aren’t even nerds. It’s all good. In my view, it is unlikely any person overlaps with all the things, although there are people who get dangerously close.

If I learned anything from reading the comments, besides ‘don’t read the comments’, it is this: I need to remind myself that we can all learn so much from each other, because skills overlap. That requires not a ‘X is shit’ attitude, but a ‘how does X work?’ one.

Originally posted as Overlapping skills in front-end development on Hidde's blog.

Heading structures are tables of contents

The heading structure of a web page is like its table of contents. It gives people who can’t see your page a way to navigate it without reading everything.

To be clear, by ‘heading structure’ in this post, I mean the heading elements in your HTML: <h1> to <h6> . These elements can be strongly intertwined with what they look like, but for our purposes it is the markup that matters.

The best analogy I’ve been able to come up with for heading structures, is the feature in Microsoft Word that lets users generate a table of contents automatically. It is used a lot by all kinds of people, in all kinds of environments (in long corporate documents, but also in academia). If you’ve set document headings correctly, it lists all sections and subsections. It even remembers, and updates, which page they are on.

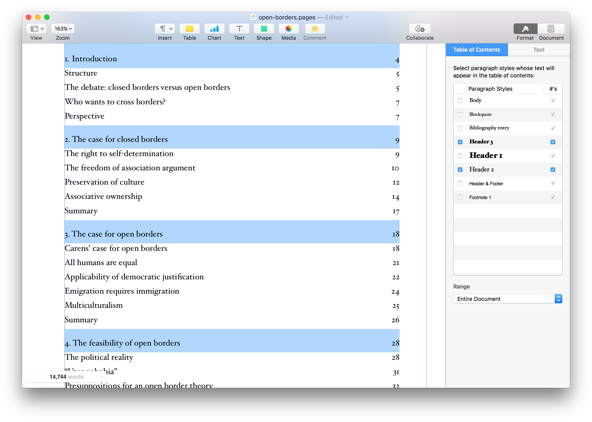

Example of the automagic table of contents feature in Pages. It even lets you select which heading levels to include!

Example of the automagic table of contents feature in Pages. It even lets you select which heading levels to include!

All websites have this too, as a similar feature is built into most screenreaders. In VoiceOver, for example, users can press a button to see a list of all headings and use this to navigate a page. In fact, this is a common way for screenreader users to get around your page without reading everything.

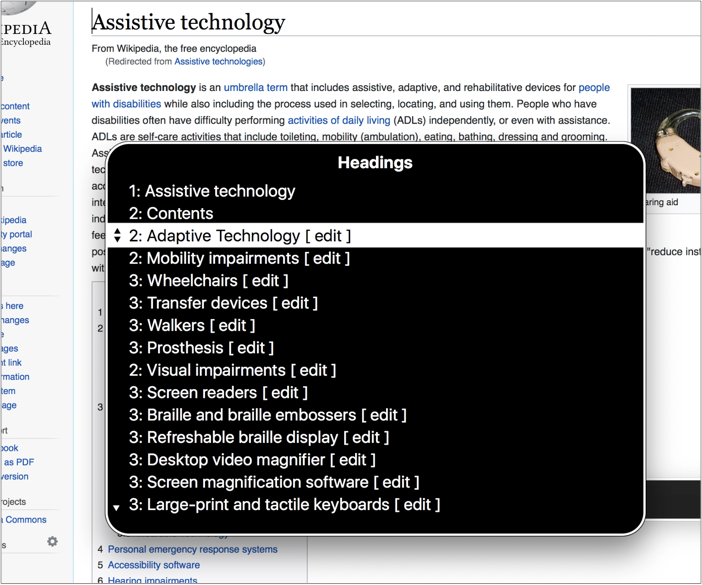

The headings feature in action on Wikipedia. Note that Wikipedia also lists the headings explicitly, with section numbering.

The headings feature in action on Wikipedia. Note that Wikipedia also lists the headings explicitly, with section numbering.

Only use headings to identify sections

To let users get the best navigate-by-headings experience, only use heading elements for content that actually identifies a section. Ask ‘would this be useful in my table of contents?’, and if the answer is no, best choose a different HTML element. This way, only table of contents material makes it into your heading structure.

For this reason, by the way, I recommend to avoid having headings be part of user generated content (as in: content added not by content specialist, but by users of your site). If you offer Markdown for comments, for example, headings in those comments could mess with the usability of your heading structure.

If you choose something to be a header, make sure it describes the section underneath it. This can be hard to get right, you might have great puns in your headings, or maybe they were written by a SEO expert.

Visually hidden headings

Not all sections have headings, often the visual design makes it clear that something is a distinct piece of content. That’s great, but it doesn’t have to stop a section from also showing up in your table of contents. Hidden headings to the rescue!

A hidden heading is one that is ‘visually hidden’, this is content that is not visual on screen, but it exists in your markup and screenreaders can use it:

<h2 class="visually-hidden">Contact information</h2>

<!-- some content that looks visually a lot like contact

information, with icons and a receptionist stock

photo that makes it all very obvious-->(More about CSS to visually hide)

The heading goes into your virtual table of contents, but it is not visible on screen.

Note that visible headings are much preferred to hidden headings. There are two problems in particular with hidden headings:

- Like with other hidden content, it can easily be forgotten about by your future self or the next team member. Hidden content that is not up to date with the visible content is unhelpful, so it is a bit of a risk.

- Serving slightly different content may cause confusing conversations, for example if an AT user and a sighted user discuss a page and only one of them knows that there is a heading.

‘Don’t skip heading levels’

Although WCAG 2 does not explicitly forbid skipping heading levels, and this is controversial, I would say it is best not to skip heading levels.

If a contract has clause 2.4.2, it would be weird for there not to be a 2.4 — the former is a subclause of the latter. It would be weird for the subclause to exist without the main clause.

The most common reason why people skip headings is for styling purposes: they want the style that comes with a certain heading and that happens to be the wrong level for structural purposes. There are two strategies to avoid this:

- have agreement across the team about how heading levels work

- use

.h1,.h2,.h3classes, so that you can have correct heading levels, but style them however you like

The former is what I prefer, on many levels, but if it is a choice between weird CSS and happy users, that’s an easy one to make.

Automatically correct headings

The outline algorithm mentioned in HTML specifications is a clever idea in theory. It would let you use any headings you’d like within a section of content; the browser would take care of assigning the correct levels. Browsers would determine these levels by looking at ‘sectioning elements’. A sectioning element would open a new section, browsers would assume sections in sections to be subsections, and headings within them lower level headings.

There is no browser implementing the outline algorithm in a way that the above works. One could theoretically have automated heading levels with clever React components. I like that idea, although I would hesitate adding it into my codebases. That leaves us with manually choosing plain old headings level, from 1 to 6.

Conclusion

Heading structures give screenreader users and others a table of contents for our sites. By being conscious of that, we can make better choices about heading levels and their contents.

Originally posted as Heading structures are tables of contents on Hidde's blog.

Let's serve everyone good-looking content

In Benjamin’s poll, the second most voted reason to avoid Grid Layout was supporting Internet Explorer users. I think it all depends on how we want to support users. Of any browser. Warning: opinions ahead.

What lack of Grid Layout means

Let’s look at what a browser that does not support Grid Layout actually means.

What it is not

To be very clear, let’s all agree this is not the case:

- Browsers that support Grid Layout: users see a great layout

- Browsers that don’t support Grid Layout: users see a blank page

That would be bad. Luckily, it is not that bad. CSS comes with a cascade, which includes the mechanism that the values of style rules are always set to something. Rules have a default value, which is usually what browsers will apply for you. It can be overridden by a website’s stylesheet, which in turn can also be overridden by user stylesheets. Because of the design of CSS, properties always compute to some value.

What it is

When turning an element on the page into a grid, we apply display: grid to it. At that point, it becomes a grid container and we can apply grid properties to it (and its children). If we set display: grid in an unsupported browser, the element will simply not become a grid container, and it will not get any of the grid properties you set applied. The display property will be whatever it was, usually inline or block, different elements have different defaults.

A little sideline: per spec, if you use floats (or clear), they will be ignored on children of grid containers. This is great for fallbacks.

Without Grid Layout, you still get your content, typography, imagery, colours, shadows, all of that. It will likely be displayed in a linear fashion, so it will be more or less like most mobile views. That is a perfectly ok starting point and it is good-looking content that we can serve to everyone.

Serving users good-looking content

I think our goal, rather than supporting specific browsers or specific CSS properties, should always be this: to serve users good-looking content and usable interfaces that are on-brand. I think good-looking and usable do not depend on how griddy your layout is. On-brand might, though. Some brand design guidelines come with specific grids that content needs to be layed out in. But aren’t we already used to stretching such guidelines, building responsive interfaces that work across viewports? Shouldn’t we let go, because we cannot control a user’s browser?

If for some small proportion of our users, we let go of the specific grid we created with grid layout, that will not hurt them. Likely not without any fallback, but definitely not with a simple fallback based on floats, inline-block or maybe flex and/or feature queries. But keep it simple. As Jeremy Keith wrote:

You could jump through hoops to try to get your grid layout working in IE11, […] but at that point, the amount of effort you’re putting in negates the time-saving benefits of using CSS grid in the first place.

I don’t think we owe it to any users to make it all exactly the same. Therefore we can get away with keeping fallbacks very simple. My hypothesis: users don’t mind, they’ve come for the content.

If users don’t mind, that leaves us with team members, bosses and clients. In my ideal world we should convince each other, and with that I mean visual designers, product owners, brand people, developers, that it is ok for our lay-out not to look the same everywhere. Because serving good-looking content everywhere is more important than same grids everywhere. We already do this across devices of different sizes. For responsive design, we’ve already accepted this inevitability. This whole thing is a communication issue, more than a technical issue.

Save costs and sanity

If we succeed in the communication part, we can spend less time on fallbacks, now and in the future (I’m not saying no time, we want good-looking content). An example: that mixin we created to automatically fallback grid to flex to inline-block might look like a great piece of engineering now, it may later become a piece of hard to comprehend code. Solving the communication issue instead of the technical one, will save time in initial development costs and help prevent technical debt.

Originally posted as Let's serve everyone good-looking content on Hidde's blog.