Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Trying out spicy sections on here

This week I had some fun with <spicy-sections> , an experimental custom element that turns a bunch of headings and content into tabs. Or collapsibles. Or some combination of affordances, based on conditions you set.

Background

Introduced in Brian Kardell’s post Tabs in HTML?, the <spicy-sections> element is a concept from some folks in the Open UI Community Group. In this CG, we analyse UI components that are common in design systems and on the web. The goal is to find out which ones might be suitable additions to the platform, the HTML spec and browsers.

All design systems teams could come up with their own tabs and figure out semantics, accessibility, security and behaviours. But what if some (or all) of those things could be built into HTML, with browsers implementing smart defaults? A bit like the video element… as a developer you only need to feed it a video and some subtitles, and boom, your users can enjoy video. Maybe your specific website needs the play button to be pink or trigger confetti, but generally, there are quite a lot of websites where the default is just right.

The nice thing about platform defaults is also that it can be optimised for the platform that renders it: a select on iOS is different than a select on Microsoft Edge. They work well on these respective platforms. Yes, everyone would like more control over styling of selects, and Open UI is looking at that too (and yay, accent-color is a thing soon). But can we know which styles a given user needs as well as the platform can?

Why spicy sections?

Tabs are among the most frequently requested components. They are also tricky. Some of the considerations:

- meaning: tabs in your browser manage windows, tabs in a webpage manage, eh, sections? These are quite distinct.

- accessibility: with ARIA, there are at least two ways to do tabs (eg activate on focus or not?), and in some user tests I saw, users prefers ARIA-less tabs

- what about disabled tabs and user dismissable ones?

- overflow: what if not all tabs fit on the screen? scrollbars?

(The Tabs Research from Open UI CG has many more tab engineering considerations)

The overflow issue begs the question: does content displayed in tabs always belong in tabs, or might there be better controls in some situations? Maybe on small screens we need to get rid of the tabs and use collapsibles? (Maybe we need to ‘uncontrol’ them in specific cases, like print?)

This makes all the more sense if you consider tabs in web pages are really just a different way to display sections and their headings. Headings are tables of contents, after all. “Spicy sections”, then, would be a web platform feature that lets you display sections in different ways: linear, as is the default way to display sections now, as tabs or as collapsibles. You pick which based on constraints, and media queries are the way the spicy-sections demo defines those constraints.

Yes, <spicy-sections> is a demo, the element exists to explore ideas and start the conversation. Brian encourages you to share your thoughts:

Play with it. Build something useful. Ask questions, show us your uses, give us feedback about what you like or don’t. This will help us shape good and successful approaches and inform actual proposals.

As Brian says in his post: it is critical that web developers see these proposals way before they exist in browsers. So if you happen to be a front-end developer reading this… consider if you like this experiment, share your thoughts or questions, don’t feel shy to open a GitHub issue.

Four sections, but spicier

On this website I have a fairly boring page that lists some stuff I do as a freelancer: services. Each service has a h2 and a bit of content. I decided to use this for testing the spicy-sections element IRL.

To get it to work, I included SpicySections.js, a JavaScript class that defines a custom element. The element looks in your CSS for a definition of when you want which affordances. I went for this configuration:

- collapsibles when

max-width: 50em(my mobile state) matches - tabs when

min-width: 70emmatches - otherwise, just the headings and content as they are

I could set this in my CSS, using:

spicy-sections {

--const-mq-affordances:

[screen and (max-width: 50em) ] collapse |

[screen and (min-width: 70em) ] tab-bar;

}I rewrote my markup to have the following expected structure:

<spicy-sections>

<h2>Name of heading</h2>

<div>

content be here

</div>

… repeat the h2 and div for more sections

</spicy-sections>(also works with other headings; h1, h3, etc)

Note: this isn’t final syntax, it could be something else entirely, suggestions are welcomed.

Some overrides

After I had ensured my markup had the right shape, I included the SpiceSections JavaScript and I set my constraints in CSS, it worked very much as advertised. There were two things I tweaked.

Vertical tabs

With spicy-sections, you’re using headings as tab names. It seems my page has quite long headings. Horizontally, I didn’t have sufficient space, so I wanted mine to go vertical instead.

I got this to work by adding an extra affordance to the web component class, some code to set aria-orientation to vertical and a bit of CSS to make it work visually. I set white-space to normal and made spicy-sections a flex container in the row direction, for easy same height columns.

I could have done this all in CSS, except for aria-orientation, but I am unsure about the benefit of the attribute here: arrow keys for both orientations are supported by default.

Overriding a margin

In my website’s CSS, I have this line (don’t judge 😬):

*,

*::before,

*::after {

margin: 0;

padding: 0;

box-sizing: border-box;

}It somehow overwrote the right margin on the arrows that spicy-sections throws in for the collapsed view. No biggie, with CSS’s excellent cascading functionality this was easy to fix.

Nesting

I have also put some spicy-sections inside my spicy-sections: I have some ‘examples’ listed on the side on larger screens, it made sense to me to show them collapsed on smaller screens. This can be done with a combination of spicy-sections:

<spice-sections>

<h2>A section</h2>

<div>

<spicy-sections>

<h3>Oh my, I am nested!</h3>

<div/>

</spicy-sections>

</div>

…

</spicy-sections>

and this CSS:

.spicy-services-examples {

--const-mq-affordances:

[screen and (max-width: 50em) ] collapse;

}So basically, I only list one affordance and it only applies to “small screens”, or what that means on this site.

Thoughts

This is all a long winded way to say: I quite like the idea of conditionally changing the appearance of sections. I think it makes sense on the web, because our sites and apps are viewed on so many different screen types and sizes (screen spanning, anyone?). Horizontal tabs are probably not always the best affordance, other affordances make sense in some situations, so a mechanism to switch between them is useful.

The way the experimental component works happens to be very styleable. When I was implementing it on my site, I felt I could make everything look exactly the way I wanted it to look. The tabs are just h2 elements and you can do whatever you want to them, using the styling language we all know and love: CSS.

Reusing media query-like syntax for defining when to use which affordances is helpful. Folks who build responsive websites will be used to them already.

There are also some uncertainties that came to my mind:

- will people get it? Wrapping some content into a

spicy-sectionssections element fits well into the way I think about content on the web, I think about markup a lot, it matters to me. I fear it could feel weird to others, especially designers and developers who aren’t very concerned with markup, or who don’t see headings as tables of contents - is this easy to author in a CMS? In theory this would work well with any CMS content, it could be used with CMSes that exist today, because the markup that is required is “just” headings and content. There may be some trickery required to wrap the content underneath each heading into a

div, and the set of sections into the right element, but that should be minor. - are there other affordances that are not in the current proposal? Maybe something that automatically generated a table of contents kind of thing, like GitHub does for READMEs?

- could it confuse users that semantics and accessibility meta data (roles, states) can change based on constraints?

Wrapping up

Thanks for reading this write-up! If you like, please play with Brian’s demo on Codepen, perhaps use spicy-sections somewhere and give feedback if you have any.

Originally posted as Trying out spicy sections on here on Hidde's blog.

How AI is made matters, confirms “Atlas of AI”

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is often described as smart, efficient and superhuman. That sounds quite nice, but it leaves out a lot of details. In her book Atlas of AI, Kate Crawford maps out the power systems, impact on society and stakes that come with deploying AI. That’s important, because we, and the systems that affect us, increasingly rely on these technologies.

There are lots of worthwile pursuits in AI: we can make computers understand our speech, teach medical devices to recognise irregularities in scans and analyse financial transactions for fraud. But there is plenty of applications that may not actually contribute all that much, or are downward hostile if you consider what could go wrong. Systems deployed to surveil workers, filter resumes or drive cars (sorry) may not be worth their damage.

Natural resources and people

The impact of AI starts with the raw materials of machines, Crawford explains. Computers need chips and those require rare earth materials like tin. It’s easy to forget about that: mining such materials isn’t without consequences. It badly affects workers (and their conditions when working in mines), their direct environment (pollution) and the earth at large. Once the chips exist and machines run, there is also an environmental impact. The data centres that compute our data require enormous amounts of gas, water and electricity. One of the largest US data centres uses 1.7 million gallons of water per day, is just one of the many examples Crawford provides. When a company says ‘our product uses AI’, their product also uses these raw materials, these data centres and this energy.

Reassuringly, most big tech companies have very green ambitions, like powering 100% of their data centres with renewable energy. This is good. But when not all of the world’s energy is renewable, we’ve got to be sure there are good reasons for any energy that is used. We’ve got to focus on using less of it, and endlessly processing ginormous amounts of data does not help.

Input data and classification

Crawford also writes about the basic ingredient for AI and specifically machine learning: data. To teach machines about a thing, we need to show them examples of the thing. To produce AI, a company needs to collect data, ‘mine’ it, if you will. Data, like text messages, photos, audio or video. It is often collected without the consent of the people involved, like the people who are in the photos. Crawford warns us against ‘the unswerving belief that everything is data and is there for taking’ (AAI, 93).

There are exceptions, like Common Voice, a Mozilla project that aims to ‘teach machines how real people speak’ by asking people to ‘donate their voice’. The teaching machines part is not unlike other machine learning projects, but the data collection is. Common Voice data is not taken from some place, people provide it consentually and for the very purpose of training machines. This is uncommon (pardon the pun).

And then there is the issue of context. When images become data, context is considered irrelevant, it no longer matters. They serve to optimise technical performance and nothing else. This data is now seen as neutral, but, explains Crawford, it is not:

‘Even the largest trove of data cannot escape the fundamental slippages that occur when an infinitely complex world is simplified and sliced into categories’ (AAI, 98)

Taking data out of context also doesn’t remove all context. A data set could affect privacy in unexpected ways. Crawford discusses a set of data from taxi rides, that may have looked quite innocent and useful from the outset. What could go wrong? Well, from the data, researchers could deduce religions, home addresses and strip club visits.

Classification

Machine learning requires input data to be classified. This is a fire hydrant, that is a bicycle. Some firms pay people through Mechanical Turk… there are workers who spend all day describing images. Other companies demand the work to be done for free by users who want to login (hi recaptcha).

Perhaps more important than who does the work are the philosophical problems of classification. Is there a fixed set of categories? Does everything neatly fit in them? Such questions have boggled philosophers’ minds for, literally, millenia. It’s safe to say most would say no to either question. Yet, AI firms seem more confident. They have to, as classification of data is at the heart of how machine learning works.

The harm caused by classification problems depends on the subject, but it is widespread. Maybe the AI that was trained with some wrongly classified fire hydrants won’t cause too much trouble. But there are endlesss examples of AI exhibiting awful bias, including towards race and sexual orientation. Bias in AI has been seen as a bug to be fixed, but it should be seen as a problem of classification itself. ‘Classification is an act of power’, says Crawford (AAI, 127). The categories can be forgotten and invisible once their work in the model training phase is over, but their impact remains.

You can’t fix bias by merely diversifying a set of data, Crawford says:

‘The practice of classification is centralizing power: the power to decide which differences make a difference’ (AAI, 127)

Sometimes researchers measure the wrong thing, because are constrained by what they can measure. For example, it’s easy to measure skin colour, but it’s not the thing to measure if you’re after understanding something about race or ethnicity. It doesn’t work that way… ‘the affordances of the tools become the horizon of truth’, Crawford concludes.

Open data collections often show categories that reinforce racism and sexism, and that’s just the sets we can see. Is there a reason to assume the sets of Facebook and Google avoided these problem?

Emotion recognition and warfare

The last two chapters of “Atlas of AI” consider two of the scariest answers to ‘what could possibly go wrong?’: AI tech for emotion recognition and warfare.

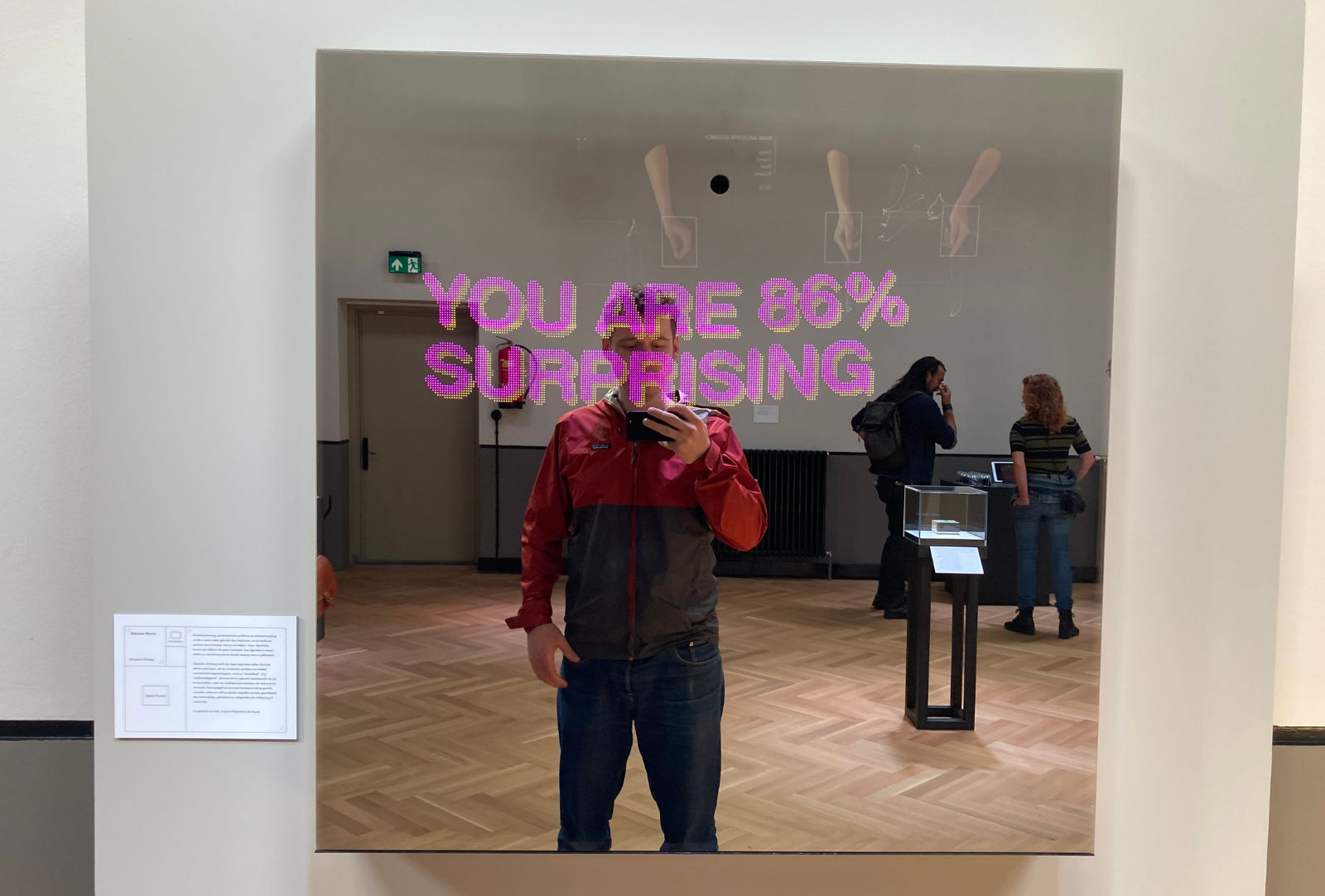

Me at The Glass Room in Leeuwarden in front of an art work about emotion recognition

Research in emotion recognition, Crawford writes, comes from a ‘desire to extract more information about people than they are willing to give’ (AAI, 153). It is already in use by HR departments to scan applicants and try and match their facial expressions to personality traits.

Can it work? Scientists including Paul Ekman tried to find out whether emotions are universal. Some were confident, but as of yet there is no consensus on which emotions exist and how they manifest (AAI, 172). Crawford explains there is growing critique doubting the very possibility that there is a clear enough relationship between facial expressions and emotional states (AAI, 174). It’s merely correlations, she says:

In many cases, emotion detection systems do not do what they claim. Rather than directly measuring people’s interior mental states, they merely statistically optimize correlations of certain physical characteristics among facial images (AAI, 177)

So, like with other AI systems, AI for emotion recognition relies on categorisation, which Crawford explained is flawed and an act of power, so it has many of the same problems:

[An analysis of the state of emotion recognition] returns us to the same problem we have seen repeated: the desire to oversimplify what is stubbornly complex, so that it can be easily computed, and packaged for the market.

And while this may work for companies selling AI systems, the end result is likely a lack of nuance:

AI systems are seeking to extract the mutable, private, divergent experiences of our corporeal selves, but the result is a cartoon sketch that cannot capture the nuances of emotional experience in the world.

Governments use AI for warfare, in the US the ‘Third Offset’ strategy includes leveraging Big Tech to create infrastructure of warfare (189). In “Project Maven”, the US Department of Defense paid Big Tech firms to analyse military data from outside the US, like drone footage, to build AI systems that could recognise ‘vehicles, buildings and humans‘ (AAI, 190)

Crawford describes a shift from debating whether to use AI in warfare at all, to, as former Google CEO Eric Schmidts said, whether AI would be able to ‘kill people correctly’ (AAI, 192)

‘Militarised forms of pattern detection’, Crawford explains, go beyond national interests when companies like Palantir sell their technology widely (eg local law enforcement and supermarket chains). They are focused not on enemies of the state, but ‘directed against civilians’. Machine learning based patten recognition tech is used to find ‘illegal’ immigrants to deport (‘illegal’, because no humans are illegal). In Europe, IBM was tasked to use data analysis to assign refugees a ‘terrorist score’, capturing the likelihood of them being a terrorist. This would be a bad idea if AI systems were 100% able to make such distinctions, and let’s be clear: they can never be. Because of the inevitability of bias and the very nature of categorisation. If even humans don’t universally agree about what constitutes a terorrist, and they don’t, how can any human categorisation we do successfully help teach machines?

When systems impact government decisions, they requires oversight, and there is very little of that, explains Crawford (AAI, 197). Without that, we risk making things worse, she says:

Inequity is not only deepened, but tech-washed, justified by the systems that appear immune to error yet are, in fact, intensifying the problems of overpolicing and racially biased surveillance

Summing up

Atlas of AI provides insight in what we give up when employing AI. There may be applications that are mostly helpful and little harmful, like language. There are applications that probably harm more than help, like emotion and warfare.

The book also reassures us that some things may not be as computable as they seem. Good categorisation is hard for humans and harder for machines. There is this fantastic tv show broadcasted on Dutch television called Zomergasten: a person of interest is interviewed for 3 hours straight on live television, and they bring in their favourite video fragments. YouTube may have state of the art machine learning powered recommendation engines, the suggestions these people bring often delight and surprise me more.

Above all, Atlas of AI will give you a fresh perspective that you can use when you read about the next thing AI is claimed to solve. Yes, the possibilities are promising. The features often cool. But we’ve got to keep our feet on the ground and assess AI technologies carefully.

The post How AI is made matters, confirms “Atlas of AI” was first posted on hiddedevries.nl blog | Reply via email

How AI is made matters, confirms “Atlas of AI”

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is often described as smart, efficient and superhuman. That sounds quite nice, but it leaves out a lot of details. In her book Atlas of AI, Kate Crawford maps out the power systems, impact on society and stakes that come with deploying AI. That’s important, because we, and the systems that affect us, increasingly rely on these technologies.

There are lots of worthwile pursuits in AI: we can make computers understand our speech, teach medical devices to recognise irregularities in scans and analyse financial transactions for fraud. But there is plenty of applications that may not actually contribute all that much, or are downward hostile if you consider what could go wrong. Systems deployed to surveil workers, filter resumes or drive cars (sorry) may not be worth their damage.

Natural resources and people

The impact of AI starts with the raw materials of machines, Crawford explains. Computers need chips and those require rare earth materials like tin. It’s easy to forget about that: mining such materials isn’t without consequences. It badly affects workers (and their conditions when working in mines), their direct environment (pollution) and the earth at large. Once the chips exist and machines run, there is also an environmental impact. The data centres that compute our data require enormous amounts of gas, water and electricity. One of the largest US data centres uses 1.7 million gallons of water per day, is just one of the many examples Crawford provides. When a company says ‘our product uses AI’, their product also uses these raw materials, these data centres and this energy.

Reassuringly, most big tech companies have very green ambitions, like powering 100% of their data centres with renewable energy. This is good. But when not all of the world’s energy is renewable, we’ve got to be sure there are good reasons for any energy that is used. We’ve got to focus on using less of it, and endlessly processing ginormous amounts of data does not help.

Input data and classification

Crawford also writes about the basic ingredient for AI and specifically machine learning: data. To teach machines about a thing, we need to show them examples of the thing. To produce AI, a company needs to collect data, ‘mine’ it, if you will. Data, like text messages, photos, audio or video. It is often collected without the consent of the people involved, like the people who are in the photos. Crawford warns us against ‘the unswerving belief that everything is data and is there for taking’ (AAI, 93).

There are exceptions, like Common Voice, a Mozilla project that aims to ‘teach machines how real people speak’ by asking people to ‘donate their voice’. The teaching machines part is not unlike other machine learning projects, but the data collection is. Common Voice data is not taken from some place, people provide it consentually and for the very purpose of training machines. This is uncommon (pardon the pun).

And then there is the issue of context. When images become data, context is considered irrelevant, it no longer matters. They serve to optimise technical performance and nothing else. This data is now seen as neutral, but, explains Crawford, it is not:

‘Even the largest trove of data cannot escape the fundamental slippages that occur when an infinitely complex world is simplified and sliced into categories’ (AAI, 98)

Taking data out of context also doesn’t remove all context. A data set could affect privacy in unexpected ways. Crawford discusses a set of data from taxi rides, that may have looked quite innocent and useful from the outset. What could go wrong? Well, from the data, researchers could deduce religions, home addresses and strip club visits.

Classification

Machine learning requires input data to be classified. This is a fire hydrant, that is a bicycle. Some firms pay people through Mechanical Turk… there are workers who spend all day describing images. Other companies demand the work to be done for free by users who want to login (hi recaptcha).

Perhaps more important than who does the work are the philosophical problems of classification. Is there a fixed set of categories? Does everything neatly fit in them? Such questions have boggled philosophers’ minds for, literally, millenia. It’s safe to say most would say no to either question. Yet, AI firms seem more confident. They have to, as classification of data is at the heart of how machine learning works.

The harm caused by classification problems depends on the subject, but it is widespread. Maybe the AI that was trained with some wrongly classified fire hydrants won’t cause too much trouble. But there are endlesss examples of AI exhibiting awful bias, including towards race and sexual orientation. Bias in AI has been seen as a bug to be fixed, but it should be seen as a problem of classification itself. ‘Classification is an act of power’, says Crawford (AAI, 127). The categories can be forgotten and invisible once their work in the model training phase is over, but their impact remains.

You can’t fix bias by merely diversifying a set of data, Crawford says:

‘The practice of classification is centralizing power: the power to decide which differences make a difference’ (AAI, 127)

Sometimes researchers measure the wrong thing, because are constrained by what they can measure. For example, it’s easy to measure skin colour, but it’s not the thing to measure if you’re after understanding something about race or ethnicity. It doesn’t work that way… ‘the affordances of the tools become the horizon of truth’, Crawford concludes.

Open data collections often show categories that reinforce racism and sexism, and that’s just the sets we can see. Is there a reason to assume the sets of Facebook and Google avoided these problem?

Emotion recognition and warfare

The last two chapters of “Atlas of AI” consider two of the scariest answers to ‘what could possibly go wrong?’: AI tech for emotion recognition and warfare.

Me at The Glass Room in Leeuwarden in front of an art work about emotion recognition

Research in emotion recognition, Crawford writes, comes from a ‘desire to extract more information about people than they are willing to give’ (AAI, 153). It is already in use by HR departments to scan applicants and try and match their facial expressions to personality traits.

Can it work? Scientists including Paul Ekman tried to find out whether emotions are universal. Some were confident, but as of yet there is no consensus on which emotions exist and how they manifest (AAI, 172). Crawford explains there is growing critique doubting the very possibility that there is a clear enough relationship between facial expressions and emotional states (AAI, 174). It’s merely correlations, she says:

In many cases, emotion detection systems do not do what they claim. Rather than directly measuring people’s interior mental states, they merely statistically optimize correlations of certain physical characteristics among facial images (AAI, 177)

So, like with other AI systems, AI for emotion recognition relies on categorisation, which Crawford explained is flawed and an act of power, so it has many of the same problems:

[An analysis of the state of emotion recognition] returns us to the same problem we have seen repeated: the desire to oversimplify what is stubbornly complex, so that it can be easily computed, and packaged for the market.

And while this may work for companies selling AI systems, the end result is likely a lack of nuance:

AI systems are seeking to extract the mutable, private, divergent experiences of our corporeal selves, but the result is a cartoon sketch that cannot capture the nuances of emotional experience in the world.

Governments use AI for warfare, in the US the ‘Third Offset’ strategy includes leveraging Big Tech to create infrastructure of warfare (189). In “Project Maven”, the US Department of Defense paid Big Tech firms to analyse military data from outside the US, like drone footage, to build AI systems that could recognise ‘vehicles, buildings and humans‘ (AAI, 190)

Crawford describes a shift from debating whether to use AI in warfare at all, to, as former Google CEO Eric Schmidts said, whether AI would be able to ‘kill people correctly’ (AAI, 192)

‘Militarised forms of pattern detection’, Crawford explains, go beyond national interests when companies like Palantir sell their technology widely (eg local law enforcement and supermarket chains). They are focused not on enemies of the state, but ‘directed against civilians’. Machine learning based patten recognition tech is used to find ‘illegal’ immigrants to deport (‘illegal’, because no humans are illegal). In Europe, IBM was tasked to use data analysis to assign refugees a ‘terrorist score’, capturing the likelihood of them being a terrorist. This would be a bad idea if AI systems were 100% able to make such distinctions, and let’s be clear: they can never be. Because of the inevitability of bias and the very nature of categorisation. If even humans don’t universally agree about what constitutes a terorrist, and they don’t, how can any human categorisation we do successfully help teach machines?

When systems impact government decisions, they requires oversight, and there is very little of that, explains Crawford (AAI, 197). Without that, we risk making things worse, she says:

Inequity is not only deepened, but tech-washed, justified by the systems that appear immune to error yet are, in fact, intensifying the problems of overpolicing and racially biased surveillance

Summing up

Atlas of AI provides insight in what we give up when employing AI. There may be applications that are mostly helpful and little harmful, like language. There are applications that probably harm more than help, like emotion and warfare.

The book also reassures us that some things may not be as computable as they seem. Good categorisation is hard for humans and harder for machines. There is this fantastic tv show broadcasted on Dutch television called Zomergasten: a person of interest is interviewed for 3 hours straight on live television, and they bring in their favourite video fragments. YouTube may have state of the art machine learning powered recommendation engines, the suggestions these people bring often delight and surprise me more.

Above all, Atlas of AI will give you a fresh perspective that you can use when you read about the next thing AI is claimed to solve. Yes, the possibilities are promising. The features often cool. But we’ve got to keep our feet on the ground and assess AI technologies carefully.

Originally posted as How AI is made matters, confirms “Atlas of AI” on Hidde's blog.

A case for accessibility statements in app stores

In Apple’s App Store and Google’s Play Store, apps can have certain bits of meta data. Categories, localisations, price, privacy policy URL… but where is the meta field for accessibility statements?

I’m more of a web person than an app person, but my clients sometimes need to publish statements about their apps. Accessibility is important to a large part of app users, showed Dutch web consultancy Q42: in over a million app users, they saw 43% use accessibility settings.

If app stores would have a field for accessibility statements, this would be good for users, organisations and developers, plus it highlights accessibility as something to compete on.

What is an accessibility statement?

An accessibility statement shows users that you care about accessibility and helps them understand what the expected level of accessibility is on your website or application (see also: Developing an Accessibility Statement).

Sites and apps that fall under EU Directive 2016/2102 (Article 7, section 1) require an accessibility statement, in a specific format. Other sites and apps can also benefit from some form of accessibility statement.

What is included in an accessibility statement?

In their accessibility statement, website or application creators declare whether their app is fully, partially or not accessible. If one of the latter two, they also list what the known issues are. Commonly, there is also information about when the website or application plans to address each issue.

Accessibility statements also include evidence of their accessibility claims. Usually this is a full WCAG conformance evaluation report, following a methodology like WCAG-EM. But accessibility does not equal WCAG conformance, you might say. This is true, it is ‘just’ a baseline. Yet, there is no other document with such a widely agreed baseline, so it is best to use this one.

Accessibility statements can also contain a feedback mechanism (they must, if published in a country that has implemented that EU Directive). Feedback mechanisms let people find out how to request content in a format that is accessible to them (e.g. can I have that untagged PDF as a Word document?), and where to report accessibility issues.

App stores have fields for privacy statements

Both the Apple App Store and the Google Play Store have a meta field available for privacy statements.

In Apple’s ecosystem it seems to be part of App Infos, in Google Play, developers can submit it through the Google Play Console.

Google does this, because they care about user privacy. They write in their Google Play Safety Section blog post:

At Google, we know that feeling safe online comes from using products that are secure by default, private by design, and give users control over their data.

It’s framed as letting developers showcase how well they do on privacy:

This new safety section will provide developers a simple way to showcase their app’s overall safety.

I, for one, applaud this effort. User privacy is super important and explaining privacy features is helpful. A standard way to do it helps users find this information more easily.

I would say we can apply the same thinking to accessibility. As mentioned earlier, app users require accessibility. It is likely they will want to find accessibility information easily. App developers and designers work hard on ensuring their app’s accessibility, so why not give them a way to showcase that too?

Why app stores need accessibility meta info

Accessibility meta info in app stores would be good for several reasons:

- helps users understand the accessibility of an application better, and learn easily and consistently about where to file accessibility bugs or request accessible versions

- helps organisations comply better with EU Directive 2016/2102, which says they should display an accessibility statement

- helps developers show their commitment

- renders accessibility as yet another aspect to compete on for application developers, because many consumers will use this to make purchasing decisions

Conclusion

App stores can be a helpful proxy between users and app creators. The vetting mechanisms and categorisations (try to) filter out low quality. They also make it easier for users to find what they need. This is why they provide filters for user-oriented features. If that’s great for privacy, it would be great for accessibility, too. Please, app store makers? 🙏

Thanks Peter and Matijs for feedback on an earlier draft. Thanks do not imply endorsements.

The post A case for accessibility statements in app stores was first posted on hiddedevries.nl blog | Reply via email

A case for accessibility statements in app stores

In Apple’s App Store and Google’s Play Store, apps can have certain bits of meta data. Categories, localisations, price, privacy policy URL… but where is the meta field for accessibility statements?

Update: on 13 May, Apple announced Accessibility Nutrition Labels 🎉:

Accessibility Nutrition Labels bring a new section to App Store product pages that will highlight accessibility features within apps and games. These labels give users a new way to learn if an app will be accessible to them before they download it, and give developers the opportunity to better inform and educate their users on features their app supports. This includes VoiceOver, Voice Control, Larger Text, Sufficient Contrast, Reduced Motion, captions, and more.

I’m more of a web person than an app person, but my clients sometimes need to publish statements about their apps. Accessibility is important to a large part of app users, showed Dutch web consultancy Q42: in over a million app users, they saw 43% use accessibility settings.

If app stores would have a field for accessibility statements, this would be good for users, organisations and developers, plus it highlights accessibility as something to compete on.

What is an accessibility statement?

An accessibility statement shows users that you care about accessibility and helps them understand what the expected level of accessibility is on your website or application (see also: Developing an Accessibility Statement).

Sites and apps that fall under EU Directive 2016/2102 (Article 7, section 1) require an accessibility statement, in a specific format. Other sites and apps can also benefit from some form of accessibility statement.

What is included in an accessibility statement?

In their accessibility statement, website or application creators declare whether their app is fully, partially or not accessible. If one of the latter two, they also list what the known issues are. Commonly, there is also information about when the website or application plans to address each issue.

Accessibility statements also include evidence of their accessibility claims. Usually this is a full WCAG conformance evaluation report, following a methodology like WCAG-EM. But accessibility does not equal WCAG conformance, you might say. This is true, it is ‘just’ a baseline. Yet, there is no other document with such a widely agreed baseline, so it is best to use this one.

Accessibility statements can also contain a feedback mechanism (they must, if published in a country that has implemented that EU Directive). Feedback mechanisms let people find out how to request content in a format that is accessible to them (e.g. can I have that untagged PDF as a Word document?), and where to report accessibility issues.

App stores have fields for privacy statements

Both the Apple App Store and the Google Play Store have a meta field available for privacy statements.

In Apple’s ecosystem it seems to be part of App Infos, in Google Play, developers can submit it through the Google Play Console.

Google does this, because they care about user privacy. They write in their Google Play Safety Section blog post:

At Google, we know that feeling safe online comes from using products that are secure by default, private by design, and give users control over their data.

It’s framed as letting developers showcase how well they do on privacy:

This new safety section will provide developers a simple way to showcase their app’s overall safety.

I, for one, applaud this effort. User privacy is super important and explaining privacy features is helpful. A standard way to do it helps users find this information more easily.

I would say we can apply the same thinking to accessibility. As mentioned earlier, app users require accessibility. It is likely they will want to find accessibility information easily. App developers and designers work hard on ensuring their app’s accessibility, so why not give them a way to showcase that too?

Why app stores need accessibility meta info

Accessibility meta info in app stores would be good for several reasons:

- helps users understand the accessibility of an application better, and learn easily and consistently about where to file accessibility bugs or request accessible versions

- helps organisations comply better with EU Directive 2016/2102, which says they should display an accessibility statement

- helps developers show their commitment

- renders accessibility as yet another aspect to compete on for application developers, because many consumers will use this to make purchasing decisions

Conclusion

App stores can be a helpful proxy between users and app creators. The vetting mechanisms and categorisations (try to) filter out low quality. They also make it easier for users to find what they need. This is why they provide filters for user-oriented features. If that’s great for privacy, it would be great for accessibility, too. Please, app store makers? 🙏

Originally posted as A case for accessibility statements in app stores on Hidde's blog.