Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

2021: Year in review

It’s the end of the year again! This was my second full year working for myself on wizard zines.

Here are some thoughts about what I’m working towards, a bunch of things I made this year, and a few ideas and questions about 2022.

made some progress on a “mission statement”

I think the two hardest things about working for myself are working alone and having to decide what to do.

This year I spent some time trying to figure out what I’m doing with wizard zines. This is hard for me because I work in a pretty intuitive way – I have some feelings about what’s important, and even though following my feelings usually turns out well, I can’t always explain what I’m trying to do.

Here are some thoughts about what I’m trying to do:

- I’m only interested in explaining “old” established technologies (HTTP, DNS, assembly, C, etc)

- I want to help people who are learning about these “old” things for the first time today (whether they’re new to programming or just new to the thing)

- I think it’s very important to learn through experimentation and actually using the thing

- There’s a lot of hidden knowledge about these “old” tools (what are they used for? what are the common mistakes? which parts can you ignore?). I want to make that knowledge easy to find.

There’s also something which I can’t quite articulate yet, which is that computers were “simpler” in the past, and that it’s still possible in 2022 to learn programming in a “simpler” way and cut through some of the chaos and churn in modern computing.

As stated this sounds unrealistic, because you do need to use a lot of more “complicated” stuff to get things done in a real programming job. Most people can’t avoid it! But understanding the “simple” core of how computers work really gives me a lot more confidence when dealing with all of the chaos. (“I don’t know what all this nonsense is but at the end of the day it’s all just assembly instructions and memory and system calls, I can figure this out”)

So I guess I want to figure out how to help other people move towards that confidence of “ok, I know how this computer stuff works, I can figure out any weird new nonsense you throw at me”. That seems ambitious and it might be unrealistic for a collection of a few zines and and blog posts and websites but it feels important to me.

educational websites!

This year I felt more excited about making websites than making zines and so I spent more time building websites than I did writing zines. I think this is because:

- the way I learn things is by doing, not by reading

- I feel really comfortable experimenting and breaking things on my computer, but I get the impression that not everyone feels the same level of comfort

- writing code is fun

I’m not going to write about each project at length here because I already wrote long blog posts about each one, but here’s a list of all of the educational websites I made this year (and one command line tool):

- mysteries.wizardzines.com (blog post), a choose-your-own-adventure debugging game

- nginx playground (blog post), where you can do nginx experiments

- mess with dns (blog post), where you can do DNS experiments. I built this one with Marie Claire LeBlanc Flanagan.

- dnspeep (blog post), a command line tool for spying on your DNS queries

- a simple dns lookup tool (blog post), a friendly website version of

dig - what happens behind the scenes when you make a DNS query, a friendly website version of

dig +trace - a sort of “linux challenges” site that I wrote about a lot but haven’t released yet

As you can tell, a lot of them are related to DNS :)

collaboration!

My biggest problem with working for myself is that it gets lonely sometimes, and in previous years I haven’t been very good at finding collaborators. This year I got to work with Marie on Mess With DNS. It was a lot more fun (and a lot easier!) than building it by myself would have been.

opened a print zine store!

I finally (after several years of struggling to figure it out) opened an online store that sells print versions of my zines in May.

Unlike my previous artisanal attempts where I did all the shipping myself (which was kind of fun but totally unsustainable), this time an amazing company called White Squirrel is handling the shipping.

Setting this up involved a lot of logistics (I just finished figuring out how to handle EU VAT for example), but now that it’s set up it doesn’t need too much ongoing attention except to answer occasional emails from people who run into shipping problems.

put all of my comics online!

I put all of my comics online in one place at https://wizardzines.com/comics. Here’s a blog post about that. I’m really happy about this and it’s amazing to be able to just link to any comic I want (like grep).

some partial zines!

I worked on a few zine ideas this year but did not finish any. Here are some bits and pieces that I wrote this year.

Some pages from a DNS zine draft:

- why updating DNS is slow

- the 4 types of DNS servers

- CNAME records

- DNS record types

- why we need DNS

- subdomains

- top-level domains

I also worked on a zine about debugging that I’ve been writing on and off since 2019. Here are some pages I wrote in this year’s attempt: (you can find more by searching for “debugging” at https://wizardzines.com/comics)

- track your progress

- guesses are often wrong

- why some bugs feel “impossible”

- make a minimal reproduction

- list what you’ve learned

- this flowchart

- “we think about debugging as a technical skill (and it absolutely is!!) but a

huge amount of it is managing your feelings so you don’t get discouraged and

being self-aware so you can recognize your incorrect assumptions” (this was just a tweet, not a comic)

I also wrote 3 pages about how things are represented in memory (hexadecimal, little-endian, bytes), but there’s a very long way to go on that project.

I got stuck writing these for the reason I usually get stuck finishing zines – I need to have a clear explanation in my mind of what the zine is about. The explanation looks something like “the reason many people struggle with TOPIC is because they don’t understand X, here’s what you need to know”. My first guess at what “X” is often wrong, and the farther I am away from learning the topic for the first time myself the more wrong I am.

But I have some thoughts about how to get unstuck, we’ll see what happens!

blog posts!

here are some of blog posts I wrote this year, by category:

“how things work”:

- The OSI model doesn’t map well to TCP/IP

- DNS “propagation” is actually caches expiring

- Quadratic algorithms are slow (and hashmaps are fast)

“how to use X tool”:

- What problems do people solve with strace?

- How to look at the stack with gdb

- Tools to Explore BGP

- Some notes on using esbuild

- Firecracker: Start a VM in less than a second

- Docker Compose: a nice way to set up a dev environment

meta-posts about learning and writing:

- Get better at programming by learning how things work

- Blog about what you’ve struggled with

- Patterns in confusing explanations

- Write good examples by starting with real code

- How to get useful answers to your questions

- Teaching by filling in knowledge gaps (this one was really helpful for me to write to articulate to myself what I’m trying to do)

debugging:

- Why bugs might feel “impossible”

- Debugging by starting a REPL at a breakpoint is fun

- Debugging a weird ‘file not found’ error

I’ve historically had a “never write anything negative” rule for this blog and I’m trying to back off that a little bit because it feels limiting. Specifically the posts on dns propagation, the osi model, and confusing explanations are a little more negative than what I would have written previously, and I think they’re better because of it.

Looking at this list, maybe I want to write more hands-on “how things work” / “how to use X tool” posts next year.

Also, I see people linking to Get your work recognized: write a brag document (from 2019) on Twitter all the time. I’m very happy it’s still helping people.

the business is doing well!

This past year I released a lot of free things and not as many things that cost money, but the business is doing well nonetheless and I’m happy about that.

All of the work in this post continues to be 100% funded by zine sales, which I’m grateful for.

things I might do in 2022

Here are some things I might do in 2022. I write these because it’s interesting to see at the end of the year which ones happened and which ones didn’t.

- keep working with other people.

- try to finish some zines

- make more websites where people can do computer experiments

- figure out where to take the computer mysteries project

- give a talk (I’ve taken 3 years off writing talks, but I have some ideas)

- try to understand what’s going on with this “mission statement”

some things I’m less likely to do, but that I’ve thought about:

- write an actual book (for example a book about computer networking)

- write some computer networking command line tools that are easier to use

- collaborate with someone to write a zine about a topic that I know almost nothing about (like databases)

- spend more (than 0) time reading papers about CS education

some questions

Here are some questions I have going into 2022.

- What’s the scope of the “zines” project? How many more do I want to write?

- What’s hard for developers about learning to use the Unix command line in 2021? What do I want to do about it?

- If I keep making these educational websites, how can/should I measure how much they’re used? (I’m thinking here about this paper by Philip Guo about python tutor’s design guidelines)

- Do any of my educational websites need to make money, or can I keep releasing them for free?

New tool: Mess with DNS!

Hello! I’ve been thinking about how to explain DNS a bunch in the last year.

I like to learn in a very hands-on way. And so when I write a zine, I often close the zine by saying something like “… and the best way to learn more about this is to play around and experiment!“.

So I built a site where you can do experiments with DNS called Mess With DNS. It has examples of experiments you can try, and you’ve very encouraged to come up with your own experiments.

In this post I’ll talk about why I made this, how it works, and give you probably more details than you want to know about how I built it (design, testing, security, writing an authoritative nameserver, live streaming updates, etc)

a screencast

Here’s a GIF screencast of what it looks like to use it:

it’s a real DNS server

First: Mess With DNS gives you a real subdomain, and it’s running a real DNS

server (the address is mess-with-dns1.wizardzines.com). The interesting thing about DNS

is that it’s a global system with many different computers interacting, and so

I wanted people to be able to actually see that system in action.

problems with experimenting with DNS

So, what makes it hard to experiment with DNS?

- You might not be comfortable creating test DNS records on your domain (or you might not even have a domain!)

- A lot of the DNS queries happening behind the scenes are invisible to you. This makes it harder to understand what’s going on.

- You might not know which experiments to do to get interesting/surprising results

Mess With DNS:

- Gives you a free subdomain you can use do to DNS experiments (like

ocean7.messwithdns.com) - Shows you a live stream of all DNS queries coming in for records on your subdomain (a “behind the scenes” view)

- Has a list of experiments to try (but you can and should do any experiment you want :) )

There are three kinds of experiments you can try in Mess With DNS: “weird” experiments, “useful” experiments, and “tutorial” experiments.

the “weird” experiments

When I experiment, I like to break things. I learn a lot more from seeing what happens when things go wrong than from things going right.

So when thinking about experiments, I thought about things that have gone wrong for me with DNS, like:

- negative DNS caching making me wait an HOUR for my website to work just because I visited the page by accident

- having to wait a long time for cached record expire

- different resolvers having different cached records, which meant I got different results

- pointing at the correct IP address, but having the server not recognize the

Hostheader

Instead of viewing these as frustrating, I thought – I’ll make these into an interesting experiment with no consequences, that people can learn from! So we built a section of “Weird Experiments” where you can intentionally cause some of these problems and see how they play out.

the “useful” and “tutorial” experiments

The “weird” experiments are the ones we spent the most time on, but there are also:

- “tutorial” experiments that walk you through setting some basic DNS records, if you’re newer to DNS or just to help you see how the site works

- “useful” experiments that let actual realistic DNS tasks (like setting up a website or email)

I think I’ll add more examples of “useful” experiments later.

the experiments have different results for different people

One thing we noticed in playtesting was that the “weird” experiments don’t have the same results for everyone, mostly because different people are using different DNS resolvers. For example, there’s a negative caching experiment called “Visit a domain before creating its DNS record”. And when I test that experiment, it works as described. But my friend who was using Cloudflare (1.1.1.1) as a DNS resolver got totally different results when he tried it!

I was stressed out by this at first – it would for sure be simpler for me if I knew that everyone has a consistent experience! But, thinking about it more, one of the basic facts about DNS is that people don’t have a consistent experience of it. So I think it’s better to just be honest about that reality.

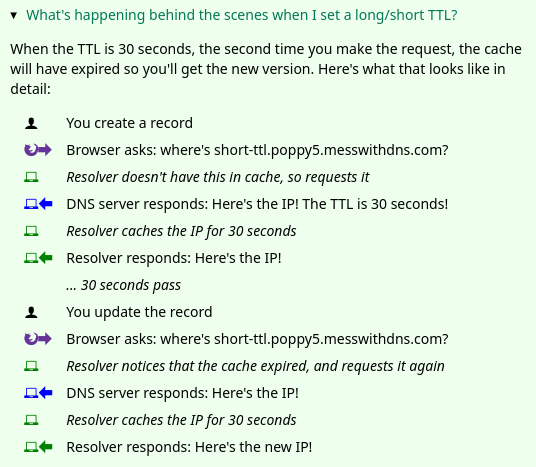

giving “behind the scenes” explanations

For some of the experiments, it’s not really obvious what’s happening behind the scenes and I wanted to provide explanations at the end.

I often make comic to show how different computers interact. But I didn’t feel like drawing a bunch of comics (it takes a long time, and they’re hard to edit).

So we came up with this format for showing how the different characters interact, using icons to identify each character. It looks like this:

Honestly I think this could probably be made clearer and I don’t love the design of the icons, but maybe I’ll improve it later :)

Okay, that’s everything I have to say about the experiments.

design is hard

Next, I want to talk about is the website’s design, which was a challenge for me.

I built this project with Marie Claire LeBlanc Flanagan, a friend of mine who’s a game designer and who thinks a lot about learning. We pair programmed on writing all the experiments, the design and the CSS.

I used to think that design is about how things look – that websites should look nice. But every time I talk to someone who’s better at design than me, the first question they always ask instead is “okay, how should this work?“. It’s all about functionality and clarity.

Of course, the site isn’t perfect – it could probably be more clear! But we definitely improved it along the way. So I want to talk about how we made the website more clear by doing user testing.

user testing is incredibly helpful

The way we did user testing was to observe a few people using the website and get them to narrate their thoughts out loud and see what’s confusing to them.

We did 5 of these tests (thanks so much to Kamal, Aaron, Ari, Anton, and Tom!). We came out of each test with like 50 bullet points of notes and possible things to change, and then we needed to distill them into actual changes to make. Here are 3 things we improved because of the user testing:

1. the sidebar

One thing we noticed was – we had this sidebar with experiments people could try. It looked like this, and I originally thought it was okay.

But in the user testing, we saw that people kept getting confused and lost in the sidebar. I really didn’t know how to improve it, but luckily Marie is better at this than me and we came up with a different design that better isolates the information about each experiment. Here’s a gif:

Also, everything in that gif implemented in pure CSS with a <details> tag which I

thought was cool. (here’s the codepen I learned this from)

2. the terminology

Another thing we learned in user experience testing was that a lot of people were confused about the DNS terms we were using like “A record” or “resolver”. So we wrote a short DNS dictionary to try to help with that a bit.

3. the instructions

Originally, in the instructions I’d written something like

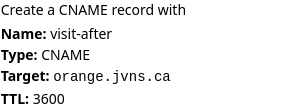

Create a CNAME record that points visit-after.fox3.messwithdns.com at orange.jvns.ca with a TTL of 3600

In the playtesting, we noticed that people took a long time to parse that sentence and translate it into which fields they needed to fill in. So we changed the instructions to look like this instead:

That feels a lot clearer to me.

That’s all I’ll say about the design, let’s move on to the implementation.

frontend test automation is amazing

Even though it’s pretty small, this is a bigger Javascript project than I’ve done previously. Usually my testing strategy for Javascript is “write a bunch of terrible untested code, manually test it, hope for the best”.

But when taking that approach this time, I kept breaking the site and I got a familiar feeling of “JULIA, you need to write TESTS, come on, this is ridiculous”.

I know about frontend test automation frameworks like Selenium, but I hadn’t used them for ages. I asked Tom what I should use, he suggested Playwright, so I used that and it worked great.

All of the Playwright tests are integration tests which is really helpful – even though it’s a frontend testing framework, the integration tests have helped me find a bunch of bugs on the backend too.

Here’s an example of one of my tests, that makes sure that when I make a DNS request to the backend it appears in the frontend. (This one broke just the other day when I was refactoring the backend!)

test('empty dns request gets streamed', async ({ page }) => {

await page.goto('http://localhost:8080')

await page.click('#start-experimenting');

const subdomain = await getSubdomain(page);

const fullName = 'asdf.' + subdomain + '.messwithdns.com.'

await getIp(fullName);

await expect(page.locator('.request-name')).toHaveText(fullName);

await expect(page.locator('.request-host')).toHaveText('localhost.lan.');

await expect(page.locator('.request-response')).toContainText('Code: NXDOMAIN');

});

I won’t really explain the details but hopefully that gives you a basic idea. These tests are still a little flaky for reasons I don’t quite understand, but I think maybe that’s normal with frontend automation? I’ve found them pretty easy to write, pretty reliable, and super useful.

Okay, now let’s move to talking about the backend, which was more in my comfort zone. This was fun to build and there were a bunch of things I thought were interesting.

I’ve put a snapshot of the backend’s code on GitHub if you want to read it.

the authoritative DNS server

I needed to write an authoritative DNS server, and I took my usual approach when trying to do something I haven’t done before:

- start with an empty program that does almost nothing (copied from How to write a DNS server in Go)

- read 0 documentation and just start implementing stuff

- see what breaks

- Begrudgingly read a little bit of documentation to fix things that break

I used this wonderful DNS library https://github.com/miekg/dns which I used previously for the backend of https://dns-lookup.jvns.ca/.

Here’s what my main ServeDNS function looks like, with some error handling and logging removed:

func (handle *handler) ServeDNS(w dns.ResponseWriter, request *dns.Msg) {

// look up records in the database

msg := dnsResponse(handle.db, request)

w.WriteMsg(msg)

// Save the request to the database and send it to any clients who have a websocket open

remote_addr := w.RemoteAddr().(*net.UDPAddr).IP

LogRequest(handle.db, r, msg, remote_addr, lookupHost(handle.ipRanges, remote_addr))

}

following the DNS RFCs? not exactly

I think I’m doing a pretty bad job of following the DNS RFCs. Basically my algorithm for which records to return is:

for which DNS response code to return:

- return

NXDOMAINif I don’t have any records for a name, andNOERRORif I do have a record - return a

REFUSEDerror if someone requests a name that doesn’t end with.messwithdns.com. - return

SERVFAILif I run into some kind of error like not being able to connect to the database

for which queries to return:

- if I have a

CNAMErecord for a name, then return it no matter what query type is requested - if I get a

HTTPSquery, return any A/AAAA records I have. (I’m doing this because it’s what Cloudflare seems to do and I get a lot of HTTPS DNS queries, I spent a few minutes trying to read the IETF draft about what HTTPS queries are and I couldn’t really understand it so I gave up) - otherwise just return any records that match the requested type

Hopefully that’s close enough that it won’t cause any major problems. I think

there are some rules I’m not following, like if there’s already an A record

for a name I’m not supposed to let people set a CNAME record. But I’m lazy so

I did not implement that.

I did find this test suite for an authoritative DNS server which I might spend more time looking through later.

live streaming the requests with websockets and Go channels

I wanted people to be able to livestream all requests coming in for their domain. When I was first thinking about how this works, I started googling things like “firebase” and “google pubsub” and “redis” and other pub/sub or streaming systems. I started implementing it this way but then I was having trouble getting it to work and I thought… wait… I don’t want to deal with a separate service!

So instead I wrote 60ish lines of code using Go channels (stream.go). Basically every time someone opens a websocket, I create a Go channel and store it in a map. Then whenever a DNS request comes in, I can just send it to all the channels that are waiting for requests.

This seems to work great. Originally I was using SSE (server side events) instead of websockets, but for some reason it wasn’t working on one friend’s computer so I switched to websockets and that seems more reliable.

tradeoff: no distributed systems, but slower response times

Implementing my pub/sub system with Go channels means that both the DNS server and the HTTP server need to live in a single process, and so I can’t run multiple DNS servers.

Right now the single process is in Virginia, so that means the HTTP API and DNS responses are going to be slower if you’re in Tokyo or something. I decided this was okay because it’s an educational site – it’s ok if it’s a little slow!

And this means I don’t need to deal with any distributed systems, which is amazing. Distributed systems are very annoying.

The static files for the frontend are distributed though: I put the site behind a CDN which should help make everything feel faster.

finding out who owns IP addresses with an ASN database

When a DNS requests comes in, it comes from an IP address. I wanted to tell users who owns that IP address (Google? Cloudflare? their ISP?). The obvious way is to do a reverse DNS lookup. But what if that doesn’t work?

I started out by using an API to look up the owner of an IP. This worked great, but then, similarly to with the pub/sub question, I thoought – why rely on an external service? I bet I can do this myself without taking a dependency on an API that might go down.

So I googled “asn database download”, and I found this free IP to ASN database which lists every IP address and who it belongs to.

Then I just needed to implement a binary search (well, technically it was mostly Github Copilot that implemented a binary search, I just fixed the bugs), and I could look up the owner of any IP super quickly.

So the IP address lookup code does a reverse DNS lookup and then falls back to the ASN database.

some notes on picking a database

I started out using planetscale because they have a free tier and I love free tiers.

But then I realized that my application is very write-heavy (I do a database write every time a DNS request comes in!!), and their free tier only allows 10 million writes per month. Which seemed like a lot initially, but I’d already gotten 100,000 DNS queries while it was only me using the service, and suddenly 10 million really wasn’t feeling like that much.

So I switched to using a small Postgres instance with a 10GB volume. I think that should be a reasonable amount of disk space because even though I store a lot of requests, I don’t actually need to store the requests for that long – I could easily clear out old requests every hour and it probably wouldn’t make a difference.

The data volume is attached to a stateless machine running Postgres that I can easily upgrade to give it more CPU/RAM if I need to.

I’m also excited about using Postgres because my partner Kamal has a lot more experience using Postgres than me so I can ask him questions.

let’s talk about security

Like with the nginx playground, I

had some security concerns. When I started building the project, I set it up so

that anybody could set any DNS record on any subdomain of messwithdns.com.

This felt a little scary to me, though I couldn’t put my finger on exactly why

initially.

Then I implemented Github OAuth, but that felt kind of bad too – logging in adds friction! Not everyone has a GitHub account!

Eventually I chatted with Kamal about it and we decided I was concerned about 3 things:

- Accidental collisions where 2 people get assigned the same subdomain and get confused

- People trying to create phishing subdomains

- I wanted people to get short, easy-to-type in domains

So I wrote a simple login function that:

- Generates a random subdomain like

ocean8that’s never been used before - Saves

ocean8to a database table so nobody else can take it - Sends a secure cookie to the client (using

gorilla/securecookie) - Then the user (you!) can make any changes you want to

ocean8.messwithdns.com.

Also the website’s domain (https://messwithdns.net)

is hosted on a different domain entirely than the domain where users can set

records (which is https://messwithdns.com). So that means that if someone somehow does set a record on messwithdns.com at least it won’t take the site down.

some static IP addresses

One more quick note about the experiments: I wanted to have some IP addresses people could use in their experiment if they wanted. So I set up two static IPv4 addresses: orange.jvns.ca and purple.jvns.ca. They show a picture of an orange and some grapes respectively, so you can easily see which is which.

It’s important that each one has a dedicated IP address because they’ll be accessed using a bunch of different domains, so I couldn’t use the domain name to decide how to route the request.

that’s all

I hope this project helps some of you understand DNS better, and I’d love to hear about any problems you run into. Again, the site is at https://messwithdns.net and you can report problems on GitHub.

DNS "propagation" is actually caches expiring

Hello! Yesterday I tweeted this:

I feel like the term "DNS propagation" is misleading, like you're not actually waiting for DNS records to "propagate", you're waiting for cached records to expire

— 🔎Julia Evans🔍 (@b0rk) December 5, 2021

and I want to talk about it a little more. This came up because I was showing a friend a demo of how DNS caching works last week, and he realized that what was happening in the demo didn’t line up with his mental model of how DNS worked. He immediately brought this up and adjusted his mental model (“oh, DNS records are pulled, not pushed!“). But this it got me thinking – why did my very smart and experienced friend have an inaccurate mental model for how DNS works in the first place?

First – I’m very tired of posts that complain about how people are “wrong” about how a given piece of technology works without explaining why it’s helpful to be “right”. So here’s why I like knowing how DNS works.

having a correct mental model for DNS helps me make updates faster

A common piece of advice I see for handling DNS updates is “wait 24-48 hours”. But I am very impatient, and I do NOT want to wait 48 hours! But if I want to confidently ignore this advice (and I really do!!!), then I have to actually understand how DNS works.

And it is possible to ignore this “24-48 hours” advice sometimes! It even turns out that in some cases (like when creating a record for a new name that didn’t have any records before), you don’t need to wait for DNS updates at all! It’s the best.

And of course, knowing how DNS works makes me much more confident debugging DNS problems when things go wrong, which always feels good.

Now that I’ve hopefully made a case for why this is interesting to understand, let’s talk about how DNS updates work!

DNS is pull, not push

When you make a DNS request (for example when you type google.com in your

browser), you make a request to a DNS resolver, like 8.8.8.8.

When you create a DNS record for a domain, you set the DNS record on an authoritative nameserver.

There are 2 ways you could imagine this working:

- When an authoritative nameserver gets an update for a DNS record, it immediately starts pushing updates to every resolver it knows about (false)

- The authoritative nameserver never pushes updates, it just replies with the current record when it receives a query (true)

In fact, if you create a DNS record, it’s possible that no DNS resolver will ever know about it! For example, I just created a record for a subdomain of jvns.ca that I will not tell you. Nobody will ever make a DNS query for that subdomain (I’m not going to make one, and you can’t because I didn’t tell you what it is!), so no resolver knows about it.

new DNS records are actually available instantly

I just created a TXT record at newrecord.jvns.ca with the content “i’m a new

record”. Then a few seconds later, I went to

https://www.whatsmydns.net/#TXT/newrecord.jvns.ca

to see where that DNS record was available. And it was immediately available

everywhere in the world, even though only 10 seconds had passed. No wait!

This is how CDNs work too – if you request a new resource that hasn’t be requested before, you’ll get it right away.

why DNS updates take time: caching

But when you update a DNS record, it is slow! So why is that, if records

don’t need time to get pushed out? Well, DNS resolvers like 8.8.8.8 cache DNS

records.

And if those cached records are still valid, they’ll never request a new record! So a DNS update doesn’t fully take effect until all cached versions of that record have expired. When people say “we’re waiting for DNS to propagate”, what they actually mean is “we’re waiting for cached records to expire”.

You might think that if you have a record where the TTL is 60, resolvers will cache it for 60 seconds, so you just need to wait 60 seconds for the change to be applied. But that would be too easy! So let’s talk about a few reasons that caches could take a longer time to expire (like an hour or a day).

slow update reason 1: some resolvers ignore TTLs

We said before that for a DNS update to fully take effect, all cached versions of that record need to expire. In theory, the TTL (“time to live”) on the record determines how long resolvers cache your record before. But that would be too easy :(

Instead, very rudely, some resolvers will ignore your TTL and just cache your record for as long as you feel like! Like 24 hours!

So your DNS records updates might take more time to take effect than you’d expect from the TTL.

slow update reason 2: negative DNS caching

If you query for a DNS record that doesn’t exist, your resolver might cache the absence of that record. This has happened to me a lot of times and it’s always super frustrating – here’s how it goes:

- I visit

something.mydomain.combefore creating the DNS record - I create the record

- Then I visit it again. But it doesn’t work for a long time!!! Except after some mysterious amount of time it suddenly starts working?? Why???

One day recently I decided to actually find out why this was happening, found a Stack Overflow answer talking about it, and of course the answer is in a DNS RFC! The RFC for negative caching says that the TTL for negative caching is “the minimum of the MINIMUM field of the SOA record and the TTL of the SOA itself”.

Let’s see what that is for subdomains of jvns.ca:

$ dig soa jvns.ca

jvns.ca. 3600 IN SOA art.ns.cloudflare.com. dns.cloudflare.com. 2264245811 10000 2400 604800 3600

It’s the minimum of the SOA TTL (3600) and the last number in the SOA record’s value (3600). So negative caching will happen for an hour. And sure enough, the last time I caused this problem for myself, I waited an hour and everything worked! Hooray!

While testing this, I noticed that Cloudflare’s resolver (1.1.1.1) doesn’t seem to do negative DNS caching, but my ISP’s resolver does. Weird!

slow update reason 3: browser and OS caching

DNS resolvers aren’t the only place DNS records are cached – your browser and OS might also be caching DNS records!

For example, in Firefox I sometimes need to press Ctrl+Shift+R to force reload a page after a DNS change, even if the TTL has expired and there’s a new record available. So Firefox seems to cache a little more aggressively than my DNS resolver does.

slow update reason 4: nameserver records are cached for a long time

Just making changes to DNS records is normally relatively fast, as long as you have a short TTL. But changing your domain’s nameservers can take more time. This is because to change your nameservers, 2 things have to happen:

- Your registrar has to tell your TLD’s nameservers about the new nameservers for your domain (I don’t know exactly how long this takes or why it takes time, but it’s not instant!)

- Resolvers have cached records for your nameserver, and those records need to expire. The TTL on those records is usually something like 1 day, so this can easily take a day.

For example, I just changed the nameservers for a domain I don’t use 5 minutes ago, and step 1 isn’t even done yet!

DNS resolvers are a bit like CDNs

If you already know how content delivery networks work, here’s an analogy! The way DNS resolver caching works is similar to how CDN caching work in a couple of ways:

- they both have an origin server (for DNS, the authoritative name server, for CDNs, the HTTP origin)

- they both expire their caches at some point (for DNS, when the TTL expires or maybe later if that’s the resolver’s policy, and for CDNs based on the HTTP

Cache-Controlheader, or whatever the CDN’s policy is)

There are differences too – for example, CDNs usually have a way to purge records (which is VERY useful), and DNS often don’t. Though 8.8.8.8 seems to have a “flush cache” feature. And CDNs are much more centralized. DNS resolvers are much more difficult to work with because there are thousands of different DNS resolvers run by different organizations and running different software and there’s no way to control what they do directly.

the term “DNS propagation” feels misleading to me

I feel like the widespread use of the term “DNS propagation” is a little… misleading? I’m not going to pretend to have a better term, but the reason that so many people have an incorrect mental model of how DNS works isn’t because they’re dumb – the “propagation” terminology we use to talk about why DNS updates are slow implies an incorrect mental model! No wonder people are confused!

For most programmers, “there are a bunch of cached records you have no control over and you need to wait for them to expire” is a pretty normal and approachable concept! We deal with caching all the time, and we all know why it’s frustrating to deal with. So it seems to me like if we used a term that’s more accurate, people would default to a more correct model of how DNS works.

Of course, I’m not sure that the term “DNS propagation” is why people like my friend end up with an incorrect mental model for how DNS works. That’s a strong statement and I don’t have a lot of evidence for it! But I did get quite a few of responses to my original tweet saying that just that 1 sentence (“you’re not actually waiting for DNS records to “propagate”, you’re waiting for cached records to expire”) cleared up some confusion for them.

And I’m definitely not the first person to think that the term “propagation” is misleading. A couple of examples:

- DNS propagation does not exist

- this DNS propagation checker says on its homepage “While technically DNS does not propagate, this is the term that people have become familiar with…”

okay, DNS records actually do “propagate”.

Okay, so if DNS record don’t “propagate”, why do we use the term “DNS propagation?“. There must be a reason, right? Well, I posted on twitter about this actually, and a few people mentioned that DNS records actually do get “pushed out”. But pushing out these changes is pretty fast and it’s not why DNS updates are slow.

My understanding of this is that:

- If you run a big authoritative DNS server, you want to run it globally so that people can get DNS responses quickly no matter where they are in the world

- When there’s an update, it needs to get synced to all the other authoritative servers globally, and that syncing takes time

But this delay isn’t what people are referring to when they talk about “DNS propagation”. My guess is that in the vast majority of cases, this propagation delay is at most a couple of minutes. I’ve never actually seen this delay happening in practice when I’ve set a DNS record.

And when people talk about “DNS propagation”, they’re basically always talking about waiting for cached records to expire, which can easily take hours or days.

maybe we use the term “propagation” for historical reasons?

In the 90s, maybe DNS records really did take multiple hours to get “propagated” and pushed out, and so it was more accurate to use the term “propagation” to describe why you needed to wait? And maybe that’s why we still use the term “propagation” to talk about the reason for DNS delays? I have no idea how DNS worked in the 90s though.

this terminology is probably here to stay

I’m not trying to say here that people should stop using the term “DNS propagation” to talk about waiting for cached records to expire. I’m probably going to keep using it sometimes – it’s a very widely used term that a lot of people recognize! And if everyone in the conversation already has an accurate understanding of how DNS works, using the term “DNS propagation” of course isn’t going to suddenly make people forget how DNS actually works :)

But I do think it’s important to recognize when terms we use are potentially misleading. I think I’m going to be more careful about using it in the future, especially when explaining DNS to people who don’t have a good understanding of it yet.

that’s all!

I hope that this helps make DNS less mysterious to some of you!

Thanks to Aditya, Taylor, and Hazem for their comments on a draft of this post

How to use dig

Hello! I talked to a couple of friends recently who mentioned they wished they knew

how to use dig to make DNS queries, so here’s a quick blog post about it.

When I first started using dig I found it a bit intimidating – there are so

many options! I’m going to leave out most of dig’s options in this post and just

talk about the ones I actually use.

Also I learned recently that you can set up a .digrc configuration file to make its output

easier to read and it makes it SO MUCH nicer to use.

I also drew a zine page about dig a few years ago, but I wanted to write this post to include a bit more information.

2 types of dig arguments: query and formatting

There are 2 main types of arguments you can pass to dig:

- arguments that tell dig what DNS query to make

- arguments that tell dig how to format the response

First, let’s go through the query options.

the main query options

The 3 things you usually want to control about a DNS query are:

- the name (like

jvns.ca). The default is a query for the empty name (.). - the DNS query type (like

AorCNAME). The default isA. - the server to send the query to (like

8.8.8.8). The default is what’s in/etc/resolv.conf.

The format for these is:

dig @server type name

Here are a couple of examples:

dig @8.8.8.8 jvns.caqueries Google’s public DNS server (8.8.8.8) forjvns.ca.dig ns jvns.camakes an query with typeNSforjvns.ca

-x: make a reverse DNS query

One other query option I use occasionally is -x, to make a reverse DNS query. Here’s what the output looks like.

$ dig -x 172.217.13.174

174.13.217.172.in-addr.arpa. 72888 IN PTR yul03s04-in-f14.1e100.net.

-x isn’t magic – dig -x 172.217.13.174 just makes a PTR query for

174.13.217.172.in-addr.arpa.. Here’s how to make exact the same reverse DNS query

without using -x.

$ dig ptr 174.13.217.172.in-addr.arpa.

174.13.217.172.in-addr.arpa. 72888 IN PTR yul03s04-in-f14.1e100.net.

I always use -x though because it’s less typing.

options for formatting the response

Now, let’s talk about arguments you can use to format the response.

I’ve found that the way dig formats DNS responses by default is pretty

overwhelming to beginners. Here’s what the output looks like:

; <<>> DiG 9.16.20 <<>> -r jvns.ca

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 28629

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 1, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 4096

; COOKIE: d87fc3022c0604d60100000061ab74857110b908b274494d (good)

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;jvns.ca. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

jvns.ca. 276 IN A 172.64.80.1

;; Query time: 9 msec

;; SERVER: 192.168.1.1#53(192.168.1.1)

;; WHEN: Sat Dec 04 09:00:37 EST 2021

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 80

If you’re not used to reading this, it might take you a while to sift through it and find the IP address you’re looking for.

And most of the time, you’re only interested in one line of this response (jvns.ca. 276 IN A 172.64.80.1).

Here are my 2 favourite ways to make dig’s output more manageable.

way 1: +noall +answer

This tells dig to just print what’s in the “Answer” section of the DNS response. Here’s an example of querying for the NS records for google.com.

$ dig +noall +answer ns google.com

google.com. 158564 IN NS ns4.google.com.

google.com. 158564 IN NS ns1.google.com.

google.com. 158564 IN NS ns2.google.com.

google.com. 158564 IN NS ns3.google.com.

The format here is:

NAME TTL TYPE CONTENT

google.com 158564 IN NS ns3.google.com.

By the way: if you’ve ever wondered what IN means, it’s the “query class” and

stands for “internet”. It’s basically just a relic from the 80s and 90s when

there were other networks competing with the internet like “chaosnet”.

way 2: +short

This is like dig +noall +answer, but even shorter – it just shows the

content of each record. For example:

$ dig +short ns google.com

ns2.google.com.

ns1.google.com.

ns4.google.com.

ns3.google.com.

you can put formatting options in digrc

If you don’t like dig’s default format (I don’t!), you can tell it

to use a different format by default by creating a .digrc file in your home

directory.

I really like the +noall +answer format, so I put +noall +answer in my

~/.digrc. Here’s what it looks like for me when I run dig jvns.ca using that

configuration file.

$ dig jvns.ca

jvns.ca. 255 IN A 172.64.80.1

So much easier to read!

And if I want to go back to the long format with all of the output (which I do sometimes, usually because I want to look at the records in the Authority section of the response), I can get a long answer again by running:

$ dig +all jvns.ca

dig +trace

The last dig option that I use is +trace. dig +trace mimics what a DNS

resolver does when it looks up a domain – it starts at the root nameservers,

and then queries the next level of nameservers (like .com), and so on until it reaches the authoritative nameserver for the domain.

So it’ll make about 30 DNS queries. (I checked using tcpdump, it seems to make 2 queries to get A/AAAA records for each of the root nameservers so that’s already 26 queries. I’m not really sure why it does this because it should already have those IPs hardcoded, but it does.)

I find this mostly useful for understanding how DNS works though, I don’t think that I’ve used it to solve a problem.

why dig?

Even though there are simpler tools to make DNS queries (like dog and host),

I find myself sticking with dig.

What I like about dig is actually the same thing I don’t like about dig – it shows a lot of detail!

I know that if I run dig +all, it’ll show me all of the sections of the DNS

response. For example, let’s query one of the root nameservers for jvns.ca.

The response has 3 sections I might care about – Answer, Authority, and Additional.

$ dig @h.root-servers.net. jvns.ca +all

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 18229

;; flags: qr rd; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 0, AUTHORITY: 4, ADDITIONAL: 9

;; WARNING: recursion requested but not available

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 1232

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;jvns.ca. IN A

;; AUTHORITY SECTION:

ca. 172800 IN NS c.ca-servers.ca.

ca. 172800 IN NS j.ca-servers.ca.

ca. 172800 IN NS x.ca-servers.ca.

ca. 172800 IN NS any.ca-servers.ca.

;; ADDITIONAL SECTION:

c.ca-servers.ca. 172800 IN A 185.159.196.2

j.ca-servers.ca. 172800 IN A 198.182.167.1

x.ca-servers.ca. 172800 IN A 199.253.250.68

any.ca-servers.ca. 172800 IN A 199.4.144.2

c.ca-servers.ca. 172800 IN AAAA 2620:10a:8053::2

j.ca-servers.ca. 172800 IN AAAA 2001:500:83::1

x.ca-servers.ca. 172800 IN AAAA 2620:10a:80ba::68

any.ca-servers.ca. 172800 IN AAAA 2001:500:a7::2

;; Query time: 103 msec

;; SERVER: 198.97.190.53#53(198.97.190.53)

;; WHEN: Sat Dec 04 11:23:32 EST 2021

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 289

dog also shows the records in the “additional” section , but it’s not super explicit about

which is which (I guess the + means it’s in the additional section?). It

doesn’t seem to show the records in the “Authority” section.

$ dog @h.root-servers.net. jvns.ca

NS ca. 2d0h00m00s A "c.ca-servers.ca."

NS ca. 2d0h00m00s A "j.ca-servers.ca."

NS ca. 2d0h00m00s A "x.ca-servers.ca."

NS ca. 2d0h00m00s A "any.ca-servers.ca."

A c.ca-servers.ca. 2d0h00m00s + 185.159.196.2

A j.ca-servers.ca. 2d0h00m00s + 198.182.167.1

A x.ca-servers.ca. 2d0h00m00s + 199.253.250.68

A any.ca-servers.ca. 2d0h00m00s + 199.4.144.2

AAAA c.ca-servers.ca. 2d0h00m00s + 2620:10a:8053::2

AAAA j.ca-servers.ca. 2d0h00m00s + 2001:500:83::1

AAAA x.ca-servers.ca. 2d0h00m00s + 2620:10a:80ba::68

AAAA any.ca-servers.ca. 2d0h00m00s + 2001:500:a7::2

And host seems to only show the records in the “answer” section (in this case no records)

$ host jvns.ca h.root-servers.net

Using domain server:

Name: h.root-servers.net

Address: 198.97.190.53#53

Aliases:

Anyway, I think that these simpler DNS tools are great (I even made my own simple web DNS tool) and you should

absolutely use them if you find them easier but that’s why I stick with dig.

drill’s output format seems very similar to dig’s though, and maybe drill

is better! I haven’t really tried it.

that’s all!

I only learned about .digrc recently and I love using it so much, so I hope

it helps some of you spend less time sorting though dig output!

Someone on Twitter pointed out that it would be nice if there were a way to

tell dig to show a short version of the response which also included the

response’s status (like NOERROR, NXDOMAIN, SERVFAIL, etc), and I agree! I

couldn’t find an option in the man page that does that though.

Debugging a weird 'file not found' error

Yesterday I ran into a weird error where I ran a program and got the error “file not found” even though the program I was running existed. It’s something I’ve run into before, but every time I’m very surprised and confused by it (what do you MEAN file not found, the file is RIGHT THERE???!!??)

So let’s talk about what happened and why!

the error

Let’s start by showing the error message I got. I had a Go program called serve.go, and I was trying to bundle it into a Docker container with this Dockerfile:

FROM golang:1.17 AS go

ADD ./serve.go /app/serve.go

WORKDIR /app

RUN go build serve.go

FROM alpine:3.14

COPY --from=go /app/serve /app/serve

COPY ./static /app/static

WORKDIR /app/static

CMD ["/app/serve"]

This Dockerfile

- Builds the Go program

- Copies the binary into an Alpine container

Pretty simple. Seems like it should work, right?

But when I try to run /app/serve, this happens:

$ docker build .

$ docker run -it broken-container:latest /app/serve

standard_init_linux.go:228: exec user process caused: no such file or directory

But the file definitely does exist:

$ docker run -it broken-container:latest ls -l /app/serve

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 6220237 Nov 16 13:27 /app/serve

So what’s going on?

idea 1: permissions

At first I thought “hmm, maybe the permissions are wrong?”. But this can’t be the problem, because:

- permission problems don’t result in a “no such file or directory” error

- in any case when we ran

ls -l, we saw that the file was executable

(I’m including this even though it’s “obviously” wrong just because I have a lot of wrong thoughts when debugging, it’s part of the process :) )

idea 2: strace

Then I decided to use strace, as always. Let’s see what stracing /app/serve/ looks like

$ docker run -it broken-container:latest /bin/sh

$ /app/static # apk add strace

(apk output omitted)

$ /app/static # strace /app/serve

execve("/app/serve", ["/app/serve"], 0x7ffdd08edd50 /* 6 vars */) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

strace: exec: No such file or directory

+++ exited with 1 +++

This is not that helpful, it just says “No such file or directory” again. But

at least we know that the error is being thrown right away when we run the

evecve system call, so that’s good.

Interestingly though, this is different from what happens when we try to strace a nonexistent binary:

$ strace /app/asdf

strace: Can't stat '/app/asdf': No such file or directory

idea 3: google “enoent but file exists execve”

I vaguely remembered that there was some reason you could get an ENOENT error

when executing a program even if the file did exist, so I googled it. This led me

to this stack overflow answer

which said, very helpfully:

When execve() returns the error ENOENT, it can mean more than one thing:

1. the program doesn’t exist;

2. the program itself exists, but it requires an “interpreter” that doesn’t exist.

ELF executables can request to be loaded by another program, in a way very similar to#!/bin/somethingin shell scripts.

That answer says that we can find the interpreter with readelf -l $PROGRAM | grep interpreter. So let’s do that!

step 4: use readelf

I didn’t have readelf installed in the container and I wasn’t sure how to

install it, so I ran mount to get the path to the container’s filesystem and

then ran readelf from the host using that overlay directory.

(as an aside: this is kind of a weird way to do this, but as a result of writing a containers zine I’m used to doing weird things with containers and I think doing weird things is fun, so this way just seemed fastest to me at the time. That trick won’t work if you’re on a Mac though, it only works on Linux)

$ mount | grep docker

overlay on /var/lib/docker/overlay2/1ed587b302af7d3182135d02257f261fd491b7acf4648736d4c72f8382ecba0d/merged type overlay (rw,relatime,lowerdir=/var/lib/docker/overlay2/l/326ILTM2UXMVY64V7JFPCSDSKG:/var/lib/docker/overlay2/l/MGGPR357UOZZWXH3SH2AYHJL3E:/var/lib/docker/overlay2/l/EEEKSBSQ6VHGJ77YF224TBVMNV:/var/lib/docker/overlay2/l/RVKU36SQ3PXEQAGBRKSQRZFDGY,upperdir=/var/lib/docker/overlay2/1ed587b302af7d3182135d02257f261fd491b7acf4648736d4c72f8382ecba0d/diff,workdir=/var/lib/docker/overlay2/1ed587b302af7d3182135d02257f261fd491b7acf4648736d4c72f8382ecba0d/work,index=off)

$ # (then I copy and paste the "merged" directory from the output)

$ readelf -l /var/lib/docker/overlay2/1ed587b302af7d3182135d02257f261fd491b7acf4648736d4c72f8382ecba0d/merged/app/serve | grep interp

[Requesting program interpreter: /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2]

01 .interp

03 .text .plt .interp .note.go.buildid

Okay, so the interpreter is /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2.

And sure enough, that file doesn’t exist inside our Alpine container

$ docker run -it broken-container:latest ls /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2

step 5: victory!

Then I googled a little more and found out that there’s a golang:alpine

container that’s meant for doing Go builds targeted to be run in Alpine.

I switched to doing my build in the golang:alpine container and that fixed

everything.

question: why is my Go binary dynamically linked?

The problem was with the program’s interpreter. But I remembered that only dynamically linked programs have interpreters, which is a bit weird – I expected my Go binary to be statically linked! What’s going on with that?

First, I double checked that the Go binary was actually dynamically linked using file and ldd: (ldd lists the dependencies of a dynamically linked executable! it’s very useful!)

(I’m using the docker overlay filesystem to get at the binary inside the container again)

$ file /var/lib/docker/overlay2/1ed587b302af7d3182135d02257f261fd491b7acf4648736d4c72f8382ecba0d/merged/app/serve

/var/lib/docker/overlay2/1ed587b302af7d3182135d02257f261fd491b7acf4648736d4c72f8382ecba0d/merged/app/serve:

ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked,

interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, Go

BuildID=vd_DJvcyItRi4Q2RD0WL/z8P4ulttr6F6njfqx8CI/_odQWaUTR2e38bdHlD0-/ikjsOjlMbEOhj2qXv5AE,

not stripped

$ ldd /var/lib/docker/overlay2/1ed587b302af7d3182135d02257f261fd491b7acf4648736d4c72f8382ecba0d/merged/app/serve

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffe095a6000)

libpthread.so.0 => /usr/lib/libpthread.so.0 (0x00007f565a265000)

libc.so.6 => /usr/lib/libc.so.6 (0x00007f565a099000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 => /usr/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007f565a2b4000)

Now that I know it’s dynamically linked, it’s not that surprising that it didn’t work on a different system than it was compiled on.

Some Googling tells me that I can get Go to produce a statically linked binary by setting CGO_ENABLED=0. Let’s see if that works.

$ # first let's build it without that flag

$ go build serve.go

$ file ./serve

./serve: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, Go BuildID=UGBmnMfFsuwMky4-k2Mt/RaNGsMI79eYC4-dcIiP4/J7v5rNGo3sNiJqdgNR12/eR_7mqqrsil_Lr6vt-rP, not stripped

$ ldd ./serve

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007fff679a6000)

libpthread.so.0 => /usr/lib/libpthread.so.0 (0x00007f659cb61000)

libc.so.6 => /usr/lib/libc.so.6 (0x00007f659c995000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 => /usr/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007f659cbb0000)

$ # and now with the CGO_ENABLED_0 flag

$ env CGO_ENABLED=0 go build serve.go

$ file ./serve

./serve: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), statically linked, Go BuildID=Kq392IB01ShfNVP5TugF/2q5hN74m5eLgfuzTZzR-/EatgRjlx5YYbpcroiE9q/0Fg3zUxJKY3lbsZ9Ufda, not stripped

$ ldd ./serve

not a dynamic executable

It works! I checked, and that’s an alternative way to fix this bug – if I just set the

CGO_ENABLED=0 environment variable in my build container, then I can build a

static binary and I don’t need to switch to the golang:alpine container for my builds. I

kind of like that fix better.

And statically linking in this case doesn’t even produce a bigger binary (for some reason it seems to produce a slightly smaller binary?? I don’t know why that is)

I still don’t understand why it’s using cgo here, I ran env | grep CGO and I

definitely don’t have CGO_ENABLED=1 set in my environment, but I

don’t feel like solving that mystery right now.

that was a fun bug!

I thought this bug was a nice way to see how you can run into problems when compiling a dynamically linked executable on one platform and running it on another one! And to learn about the fact that ELF files have an interpreter!

I’ve run into this “file not found” error a couple of times, and it feels kind of mind bending because it initially seems impossible (BUT THE FILE IS THERE!!! I SEE IT!!!). I hope this helps someone be less confused if you run into it!