Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Some tiny personal programs I've written

I was talking to a friend last summer about what resources might be helpful for folks learning to program. My friend said they thought some people might benefit from a list of small and fun programming projects – the kind of thing you can do in an evening or weekend.

So let’s talk about that! I like to write small programs that have some marginal utility in my life. Kind of like this:

- ah! A minor problem in my life!

- I know, I bet I can solve this problem with CODE. YAY.

- 4 hours of happy programming ensues

This isn’t always the most practical (many of the problems I’ve solved with programming could have been solved in less time in other ways), but as long as your goal is actually to have fun programming and your programs don’t hurt anyone else, I think this is a great approach :)

So here are a few examples of small personal programming projects I’ve done. I’m not going to talk about “learning projects” where my goal was to learn something specific because I’ve already written a billion blog posts about that.

These are more about just doing something fun with no specific learning goal.

a theatre festival didn’t have a calendar

The local Fringe Festival had a bunch of shows, but there was no place I could see a calendar all one one page. So I wrote a Python script to scrape their website and generate a calendar. Here’s the code and the output.

printing out covers for tiny books

I saw a TikTok video recently where someone made miniature physical versions of the ebooks they read. I decided to try it out, so I needed to print tiny versions of a bunch of book covers. I could have resized all of them manually, but I decided to do it with programming instead.

So I wrote a little bit of HTML and CSS (tinybooks.html), converted it to a PDF, and printed it out.

getting my scanner to work better

This is barely “programming”, but I needed to scan a bunch of documents for a

family member, and I didn’t like the available software. So I wrote a tiny shell script wrapper for scanimage to

make the process simpler. This one actually helped me a lot and I still use it when

scanning.

getting a vaccine appointment

When the second COVID vaccine doses opened up, all of the slots were full. It turned out that the website’s backend had an API, so I wrote a script to poll the API every 60 seconds or so and watch for cancellations and notify me so that I could get an earlier appointment.

This didn’t turn out to be necessary (more appointments opened up pretty soon anyway and there were enough for everyone), but it was fun.

In general I try to be careful when using APIs like this in a way the developers didn’t intend to avoid overloading the site.

looking at housing market data

We were thinking of buying a condo a few years ago and I was mad that I couldn’t get any information about historical prices, so I wrote an iPython notebook that queried the API of a local real estate website to scrape some information and calculate some statistics like price per square foot over time.

I don’t think this actually helped us at all with buying a condo but it was fun.

(“using the API of local services” seems to be an ongoing theme, one of my favourite things is to use secret undocumented APIs where you need to copy your cookies out of the browser to get access to them)

crossword business cards

in 2013, I thought it might be fun to have a business card that was a crossword with some of my interests. So I wrote general software to generate crosswords from a text file. I’m pretty sure never printed the business cards but it was fun to write.

generating envelopes

I was mailing some zines a while ago, and I decided I wanted to print custom labels on every envelope – sort of a “mail merge” situation. So I wrote a Python program to go through all of the mailing address and generate some HTML and CSS. Then I turned the HTML/CSS into a PDF and printed the envelopes. This worked great.

investigating dice rolling patterns

A friend showed me a dice rolling game where you roll a bunch of dice and add up the values. I mentioned that if you roll enough dice and add up all the values, at some point it gets a lot less “random”.

But then I wanted to see exactly how much less random it gets. So I wrote a tiny program to roll 2500 dice and add up the resulting sums a bunch of times to see how it works. (presumably you could calculate the same thing with math, but it’s easier with code)

This was so little code I’ll just inline it here. (it’s Python). Here’s [the output](https://gist.github.com/jvns/e4a35ca2bad90c1a0fcaf578a803b456

import random

def roll():

return sum(random.randint(1, 6) for i in range(2500))

while True:

print(roll())

getting drawings into the Notability app

I was using an app called Squid to do drawing, and I was switching to Notability and wanted to get my old drawings into Notability. So I reverse engineered the Notability file format.

I don’t think this was ultimately that useful (I ultimately ended up switching to a different drawing app which had a real SVG import), but I had fun.

turning off retweets

This is a slightly less tiny project (it took more than one day), but I decided I didn’t want to see retweets on Twitter anymore so I wrote a small website so I could turn off retweets.

I really love tiny projects

All of these examples are more recent, but I think that when I was starting to learn to program tiny low-stakes projects like this really helped me. I love that

- they’re just for me (if it goes wrong, it doesn’t matter!)

- I can finish them in an evening or weekend (it’s not a Huge Giant Thing hanging over my head)

- if it works, there’s some tangible output in my life (like some envelopes or miniature books or a schedule a business card or a better Twitter experience)

Some things about getaddrinfo that surprised me

Hello! Here are some things you may or may not have noticed about DNS:

- when you resolve a DNS name in a Python program, it checks

/etc/hosts, but when you usedig, it doesn’t. - switching Linux distributions can sometimes change how your DNS works, for example if you use Alpine Linux instead of Ubuntu it can cause problems.

- Mac OS has DNS caching, but Linux doesn’t necessarily unless you use

systemd-resolvedor something

To understand all of these, we need to learn about a function called

getaddrinfo which is responsible for doing DNS lookups.

There are a bunch of surprising-to-me things about getaddrinfo, and once I

learned about them, it explained a bunch of the confusing DNS behaviour I’d

seen in the past.

where does getaddrinfo come from?

getaddrinfo is part of a library called libc which is the standard C

library. There are at least 3 versions of libc:

- glibc (GNU libc)

- musl libc

- the Mac OS version of libc (I don’t know if this has a name)

There are definitely more (I assume FreeBSD and OpenBSD each have their own version for example), but those are the 3 I know about.

Each of those have their own version of getaddrinfo.

not all programs use getaddrinfo for DNS

The first thing I found surprising is that getaddrinfo is very widely used

but not universally used.

Every program has basically 2 options:

- use

getaddrinfo. I think that Python, Ruby, and Node usegetaddrinfo, as well as Go sometimes. Probably many more languages too but I did not have the time to go hunting through every language’s DNS library. - use a custom DNS resolver function. Examples of this:

- dig. I think this is because dig needs more control over the DNS query

than

getaddrinfosupports so it implements its own DNS logic. - Go also has a pure-Go DNS resolver if you don’t want to use CGo

- There’s a Ruby gem with a custom DNS resolver that you can use to replace

getaddrinfo. getaddrinfodoesn’t support DNS over HTTPS, so I assume that browsers that use DoH are not usinggetaddrinfofor those DNS lookups- probably lots more that I’m not aware of

- dig. I think this is because dig needs more control over the DNS query

than

you’ll sometimes see getaddrinfo in your DNS error messages

Because getaddrinfo is so widely used, you’ll often see it in error messages related to DNS.

For example if I run this Python program which looks up nonexistent domain name:

import requests

requests.get("http://xyxqqx.com")

I get this error message:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/usr/lib/python3.10/site-packages/urllib3/connection.py", line 174, in _new_conn

conn = connection.create_connection(

File "/usr/lib/python3.10/site-packages/urllib3/util/connection.py", line 72, in create_connection

for res in socket.getaddrinfo(host, port, family, socket.SOCK_STREAM):

File "/usr/lib/python3.10/socket.py", line 955, in getaddrinfo

for res in _socket.getaddrinfo(host, port, family, type, proto, flags):

socket.gaierror: [Errno -2] Name or service not known

I think socket.getaddrinfo is calling libc getaddrinfo somewhere under the

hood, though I did not read all of the source code to check.

Before you learn what getaddrinfo is, it’s not at all obvious that

socket.gaierror: [Errno -2] Name or service not known means “that domain

doesn’t exist”. It doesn’t even say the words “DNS” or “domain” in it

anywhere!

getaddrinfo on Mac doesn’t use /etc/resolv.conf

I used to use a Mac for work, and I always felt vaguely unsettled by DNS on Mac. I could tell that something was different from how it worked on my Linux machine, but I couldn’t figure out what it was.

I still don’t totally understand this and it’s hard for me to investigate because I don’t currently have access to a Mac but here’s what I’ve gathered so far.

On Linux systems, getaddrinfo decides which DNS resolver to talk to using a

file called /etc/resolv.conf. (there’s apparently some additional

complexity with /etc/nsswitch.conf but I have never looked at

/etc/nsswitch.conf so I’m going to ignore it).

For example, this is the contents of my /etc/resolv.conf right now:

# Generated by NetworkManager

nameserver 192.168.1.1

nameserver fd13:d987:748a::1

This means that to make DNS queries, getaddrinfo makes a request to

192.168.1.1 on port 53. That’s my router’s DNS resolver.

I assumed this was getaddrinfo on Mac also just used /etc/resolv.conf but I was wrong.

Instead, getaddrinfo makes a request to a program called mDNSResponder

which is a Mac thing.

I don’t know much about mDNSResponder except that it does DNS caching and

that apparently you can clear the cache with dscacheutil. This explains one

of the mysteries at the beginning of the post – why Macs have DNS caching and

Linux machines don’t always.

musl libc getaddrinfo is different from glibc’s version

You might think ok, Mac OS getaddrinfo is different, but the two versions of

getaddrinfo in glibc and musl libc must be mostly the same, right?

But they have some pretty significant differences. The main difference I know about is that musl libc does not support TCP DNS. I couldn’t find anything in the documentation about it but it’s mentioned in this tweet)

I talked a bit more about this TCP DNS thing in ways DNS can break.

Some more differences:

- the way search domains (in

/etc/resolv.conf) are handled is slightly different (discussed here) - this post mentions that musl doesn’t support nsswitch.conf. I have never used nsswitch.conf and I’m not sure why it’s useful but I think there are reasons I don’t know about.

more weird things: nscd?

When looking up getaddrinfo I also found this interesting post about getaddrinfo from James Fisher that

straces glibc getaddrinfo and discovers that apparently calls some

program called nscd which is supposed to do DNS caching. That blog post

describes nscd as “unstable” and “badly designed” and it’s not clear to me how

widely used it is.

I don’t know anything about nscd but I checked and apparently it’s on my computer. I tried it out and this is what happened:

$ nscd

child exited with status 4

My impression is that people who want to do DNS caching on Linux are more

likely to use a DNS forwarder like dnsmasq or systemd-resolved instead of

something like nscd – that’s what I’ve seen in the past.

that’s all!

When I first learned about all of this I found it really surprising that such a widely used library function has such different behaviour on different platforms.

I mean, it makes sense that the people who built Mac OS would want to handle

DNS caching in a different way than it’s handled on Linux, so it’s reasonable

that they implemented getaddrinfo differently. And it makes sense that some

programs choose not to use getaddrinfo to make DNS queries.

But it definitely makes DNS a bit more difficult to reason about.

Things that used to be hard and are now easy

Hello! I was talking to some friends the other day about the types of conference talks we enjoyed.

One category we came up with was “you know this thing that used to be super hard? Turns out now it’s WAY EASIER and maybe you can do it now!“.

So I asked on Twitter about programming things that used to be hard and are now easy

Here are some of the answers I got. Not all of them are equally “easy”, but I found reading the list really fun and it gave me some ideas for things to learn. Maybe it’ll give you some ideas too.

- SSL certificates, with Let’s Encrypt

- Concurrency, with async/await (in several languages)

- Centering in CSS, with flexbox/grid

- Building fast programs, with Go

- Image recognition, with transfer learning (someone pointed out that the joke in this XKCD doesn’t make sense anymore)

- Building cross-platform GUIs, with Electron

- VPNs, with Wireguard

- Running your own code inside the Linux kernel, with eBPF

- Cross-compilation (Go and Rust ship with cross-compilation support out of the box)

- Configuring cloud infrastructure, with Terraform

- Setting up a dev environment, with Docker

- Sharing memory safely with threads, with Rust

Things that involve hosted services:

- CI/CD, with GitHub Actions/CircleCI/GitLab etc

- Making useful websites by only writing frontend code, with a variety of “serverless” backend services

- Training neural networks, with Colab

- Deploying a website to a server, with Netlify/Heroku etc

- Running a database, with hosted services like RDS

- Realtime web applications, with Firebase

- Image recognition, with hosted ML services like Teachable Machine

Things that I haven’t done myself but that sound cool:

- Cryptography, with opinionated crypto primitives like libsodium

- Live updates to web pages pushed by the web server, with LiveView/Hotwire

- Embedded programming, with MicroPython

- Building videogames, with Roblox / Unity

- Writing code that runs on GPU in the browser (maybe with Unity?)

- Building IDE tooling with LSP (the language server protocol)

- Interactive theorem provers (not sure with what)

- NLP, with HuggingFace

- Parsing, with PEG or parser combinator libraries

- ESP microcontrollers

- Batch data processing, with Spark

Language specific things people mentioned:

- Rust, with non-lexical lifetimes

- IE support for CSS/JS

what else?

I’d love more examples of things that have become easier over the years.

The multiple meanings of "nameserver" and "DNS resolver"

I’m working on a zine about DNS right now, so I’ve been thinking about DNS terminology a lot more than a normal person. Here’s something slightly confusing I’ve noticed about DNS terminology!

Two of the most common DNS server terms (“nameserver” and “DNS resolver”) have different meanings depending on the situation.

Now this isn’t a problem if you already understand how DNS works – I can easily figure out what type of “nameserver” is being discussed based on context.

But it can be a problem if you’re trying to learn how DNS works and you don’t realize that those words might refer to different things depending on the context – it’s confusing! So I’m going to explain the different possible meanings and how to figure out which meaning is intended.

the 2 meanings of “nameserver”

There are 2 types of nameservers, and which one the term “nameserver” means depends on the context.

Meaning 1: “authoritative” nameservers

When you update the DNS records for a domain, those records are stored on a server called an authoritative nameserver.

This is what “nameserver” means in the context of a specific domain. Here are a few examples:

- “Connect a domain you already own to Wix by changing its name servers.”

- “Almost all domains rely on multiple nameservers to increase reliability: if one nameserver goes down or is unavailable, DNS queries can go to another one.”

- “You can update the nameserver records yourself by following the steps your domain registrar may provide in the help content at their website”

Meaning 2. “recursive” nameservers, also known as “DNS resolvers”

These servers cache DNS records. Your browser doesn’t make a request to an authoritative nameserver directly. Instead it makes a request to a DNS resolver (aka recursive nameserver) which figures out what the right authoritative nameserver to talk to is, gets the record, and caches the result.

This is what “nameserver” means in the context of you browsing the internet. (“your computer’s nameservers”). Here are a few examples:

- “Changing nameservers can be a pain on some devices and require multiple clicks through a user interface. On Windows 10, for example…”

- “Are your DNS nameservers impeding your Internet experience? NEW RELEASE adds nameservers 1.1.1.1, 1.0.0.1 and 9.9.9.9”

- “Configure your network settings to use the IP addresses 8.8.8.8 and 8.8.4.4 as your DNS servers”

I prefer to use the term “DNS resolver” even though it has 2 meanings because it’s much more commonly used than “recursive nameserver”.

meanings of “DNS resolver”

A DNS resolver can either be a library or a server. (I’m sorry, I know I said that a DNS resolver is a server earlier. But sometimes it’s a library.)

Meaning 1a: “stub resolver” (library version)

A “stub resolver” is something (it can be either a library or a DNS server) which doesn’t know how to resolve DNS names itself, it’s just in charge of forwarding DNS queries to the “real” DNS resolver. Let’s talk about stub resolvers that are libraries first.

For example, the getaddrinfo function from libc doesn’t know how to look up

DNS records itself, it just knows to look in /etc/resolv.conf and forward the

query to whatever DNS server(s) it finds there.

How you can tell if this is what’s meant: if it’s part of your computer’s operating system and/or if it’s a library, it’s a stub resolver.

Examples of this meaning of “DNS resolver”:

- “The resolver is a set of routines in the C library that provide access to the Internet Domain Name System (DNS)”

- “These are the DNS servers used to resolve web addresses. You can list up to three, and the resolver tries each of them, one by one, until it finds one that works.”

- “If the command succeeds, you will receive the following message “Successfully flushed the DNS Resolver Cache.“”

Meaning 1b: “stub resolver” (server version)

Stub resolvers aren’t always libraries though, like systemd-resolved and

dnsmasq are stub resolvers but they’re servers. Your router might be running

dnsmasq.

This is also known as a “DNS forwarder”.

How you can tell if this is what’s meant: if your router is running it or it’s part of your OS, it’s probably a stub resolver.

Meaning 2: a recursive nameserver (a server)

A “recursive nameserver” (like we talked about before) is a server that knows how to find the authoritative nameservers for a domain. This is the kind of DNS resolver I was talking about in this A toy DNS resolver post a couple of weeks ago (though mine wasn’t a server).

How to tell if this is what’s meant: if it’s unbound, bind, 8.8.8.8,

1.1.1.1, or run by your ISP, then it’s a recursive nameserver.

Examples of this meaning of “DNS resolver”:

- “The DNS Resolver in pfSense® software utilizes unbound, which is a validating, recursive, caching DNS resolver…”

- “We invite you to try Google Public DNS as your primary or secondary DNS resolver…”

- “I work for a reasonably large mobile service provider and we are in the process of implementing our own DNS resolver…”

the most popular DNS server words

I also did a quick unscientific survey of which terms to refer to DNS servers were the most common by counting Google results. Here’s what I found:

- dns server: 8,000,000

- nameserver: 4,200,000

- dns resolver: 933,000

- public DNS server: 204,000

- root nameserver: 42,000

- recursive resolver: 38,500

- stub resolver: 26,100

- authoritative nameserver: 17,000

- dns resolution service: 9,450

- TLD nameserver: 7,500

- dns recursor: 5,300

- recursive nameserver: 5,060

Basically what this tells me is that by a pretty big margin, the most popular words used when talking about DNS serves are “nameserver”, and “DNS resolver”.

The more specific terms like “recursive nameserver”, “authoritative nameserver”, and “stub resolver” are much less common.

that’s all!

I hope this helps some folks understand what these words mean! The terminology is a bit messier than I’d like, but it seems better to me to explain it than to use less-ambiguous language that isn’t as commonly used in practice.

A toy DNS resolver

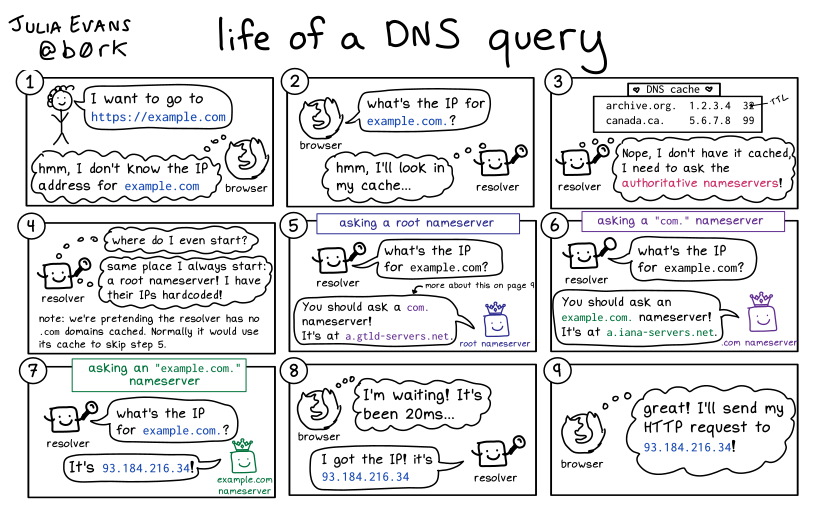

Hello! I wrote a comic last week called “life of a DNS query” that explains how DNS resolvers work.

In this post, I want to explain how DNS resolvers work in a different way –

with a short Go program that does the same thing described in the comic.

The main function (resolve) is actually just 20 lines, including comments.

I usually find it easier to understand things work when they come in the form of programs that I can run and modify and poke at, so hopefully this program will be helpful to some of you.

The program is here: https://github.com/jvns/tiny-resolver/blob/main/resolve.go

what’s a DNS resolver?

When your browser needs to make a DNS query, it asks a DNS resolvers. When they start, DNS resolvers don’t know any DNS records (except the IP addresses of the root nameservers). But they do know how to find DNS records for you.

Here’s the “life of a DNS query” comic, which explains how DNS resolvers find DNS records for you.

we’ll use a library for parsing DNS packets.

I’m not going to write this completely from scratch – I think parsing DNS packets is really interesting, but it’s definitely more than 80 lines of code, and I find that it kind of distracts from the algorithm.

I really recommend writing a toy DNS resolver that actually does the parsing of DNS packets if you want to learn about binary protocols though, it’s really fun and it’s a totally doable to get something basic working in a weekend.

So I’ve used https://github.com/miekg/dns for creating and parsing the DNS packets.

DNS responses contain 4 sections

You might think of DNS queries as just being a question and an answer (“what’s

the IP for example.com? it’s 93.184.216.34!). But actually DNS responses

contain 4 sections, and we need to use all 4 sections to write our DNS

resolver. So let’s explain what they are.

Here’s the Msg struct from the miekg/dns library, which lists the sections.

type Msg struct {

MsgHdr

Compress bool `json:"-"` // If true, the message will be compressed when converted to wire format.

Question []Question // Holds the RR(s) of the question section.

Answer []RR // Holds the RR(s) of the answer section.

Ns []RR // Holds the RR(s) of the authority section.

Extra []RR // Holds the RR(s) of the additional section.

}

Section 1: Question. This is the section you use when you’re creating a

query. There’s not much to it – it just has a query name (like jvns.ca.), a

type (like A, but encoded as an integer), and a class (which is always the

same these days, “internet”).

Here’s what the Question struct miekg/dns looks like:

type Question struct {

Name string `dns:"cdomain-name"` // "cdomain-name" specifies encoding (and may be compressed)

Qtype uint16

Qclass uint16

}

Section 2: Answer. When you make a request like this:

$ dig +short google.com

93.184.216.34

the IP address 93.184.216.34 comes from the Answer section.

The Answer, Authority, and Additional sections all contain DNS records. Different types of records have different formats, but they all contain a name, type, class, and TTL

Here’s what the shared header looks like in miekg/dns:

type RR_Header struct {

Name string `dns:"cdomain-name"`

Rrtype uint16

Class uint16

Ttl uint32

Rdlength uint16 // Length of data after header.

}

“RR” stands for “Resource Record”.

Section 3: Authority. When a nameserver redirects you to another server

(“ask a.iana-servers.net instead!“), this is the section it uses. miekg/dns

calls this section Ns instead of Authority, I guess because it contains

NS records.

Here’s an example of an record in the Authority section of a DNS response.

$ dig +noall +authority @h.root-servers.net example.com

com. 172800 IN NS a.gtld-servers.net.

com. 172800 IN NS b.gtld-servers.net.

The Authority section can also contain SOA records but that’s not relevant to this post so I’m not going to talk about that.

Section 4: Additional. This is where “glue records” live. What’s a glue record? Well, basically when a nameserver redirects you to another server, often it’ll include the IP address of that server as well.

Here are the glue records from the same query above.

$ dig +noall +additional @h.root-servers.net example.com

a.gtld-servers.net. 172800 IN A 192.5.6.30

b.gtld-servers.net. 172800 IN A 192.33.14.30

There are other things in the Additional section as well, not just glue records, but they’re not relevant to this blog post so I’m not going to talk about them.

the basic resolve function is pretty short

Now that we’ve talked about the different sections in a DNS response, I can explain the resolver code.

Let’s jump into the main function for resolving a name to an IP address.

name here is a domain name, like example.com.`

func resolve(name string) net.IP {

// We always start with a root nameserver

nameserver := net.ParseIP("198.41.0.4")

for {

reply := dnsQuery(name, nameserver)

if ip := getAnswer(reply); ip != nil { // look in the "Answer" section

// Best case: we get an answer to our query and we're done

return ip

} else if nsIP := getGlue(reply); nsIP != nil { // look in the "Additional" section

// Second best: we get a "glue record" with the *IP address* of

// another nameserver to query

nameserver = nsIP

} else if domain := getNS(reply); domain != "" { // look in the "Authority" section

// Third best: we get the *domain name* of another nameserver to

// query, which we can look up the IP for

nameserver = resolve(domain)

} else {

// If there's no A record we just panic, this is not a very good

// resolver :)

panic("something went wrong")

}

}

}

Here’s what that resolve function is doing:

1. We start with the root nameserver

2. Then we do a loop:

a. Query the nameserver and parse the response

a. Look in the “Answer” section for a response. If we find one, we’re done

a. Look in the “Additional” section for a glue record. If we find one, use that as the nameserver for the next query

a. Look in the “Authority” section for a nameserver domain. If we find one, look up its IP and then use that IP as the nameserver for the next query

That’s basically the whole program. There are a few helper functions to get records out of the DNS response and to make DNS queries but I don’t think they’re that interesting so I won’t explain them.

the output

The resolver prints out all DNS queries it made, and the record it used to figure out what query to make it next.

It prints out dig -r @SERVER DOMAIN for each query even though it’s not

actually using dig to make the query because I liked being able to run

the same query myself from the command line to see the response myself, for

debugging purposes.

-r just means “ignore what’s in .digrc”, it’s there because I have some

options in my .digrc (+noall +answer) that I wanted to disable when

debugging.

Let’s look at 3 examples of the output.

example 1: jvns.ca

$ go run resolve.go jvns.ca.

dig -r @198.41.0.4 jvns.ca.

any.ca-servers.ca. 172800 IN A 199.4.144.2

dig -r @199.4.144.2 jvns.ca.

jvns.ca. 86400 IN NS art.ns.cloudflare.com.

dig -r @198.41.0.4 art.ns.cloudflare.com.

a.gtld-servers.net. 172800 IN A 192.5.6.30

dig -r @192.5.6.30 art.ns.cloudflare.com.

ns3.cloudflare.com. 172800 IN A 162.159.0.33

dig -r @162.159.0.33 art.ns.cloudflare.com.

art.ns.cloudflare.com. 900 IN A 173.245.59.102

dig -r @173.245.59.102 jvns.ca.

jvns.ca. 256 IN A 172.64.80.1

We can see it had to make 6 DNS queries, 3 to look up jvns.ca and 3 to look up jvns.ca’s nameserver, art.ns.cloudflare.com

example 2: archive.org

$ go run resolve.go archive.org.

dig -r @198.41.0.4 archive.org.

a0.org.afilias-nst.info. 172800 IN A 199.19.56.1

dig -r @199.19.56.1 archive.org.

ns1.archive.org. 86400 IN A 208.70.31.236

dig -r @208.70.31.236 archive.org.

archive.org. 300 IN A 207.241.224.2

Result: 207.241.224.2

This one only had to make 3 DNS queries. This is because there was a glue

record available for archive.org’s nameserver (ns1.archive.org.).

example 3: www.maths.ox.ac.uk

One last example: let’s look up www.maths.ox.ac.uk. There’s a reason for this one, I promise!

dig -r @198.41.0.4 www.maths.ox.ac.uk.

dns1.nic.uk. 172800 IN A 213.248.216.1

dig -r @213.248.216.1 www.maths.ox.ac.uk.

ac.uk. 172800 IN NS ns0.ja.net.

dig -r @198.41.0.4 ns0.ja.net.

e.gtld-servers.net. 172800 IN A 192.12.94.30

dig -r @192.12.94.30 ns0.ja.net.

ns0.ja.net. 172800 IN A 128.86.1.20

dig -r @128.86.1.20 ns0.ja.net.

ns0.ja.net. 86400 IN A 128.86.1.20

dig -r @128.86.1.20 www.maths.ox.ac.uk.

ns2.ja.net. 86400 IN A 193.63.105.17

dig -r @193.63.105.17 www.maths.ox.ac.uk.

www.maths.ox.ac.uk. 300 IN A 129.67.184.128

Result: 129.67.184.128

This makes 7 DNS queries, which is more than jvns.ca, which only needed

6. Why does it make 7 DNS queries instead of 6?

Well, it’s because there are 4 nameservers involved in resolving www.maths.ox.ac.uk instead of 3. They are:

- the

.nameserver - the

uk.nameserver - the

ac.uk.nameserver - the

ox.ac.uk.nameserver

You could even imagine there being a 5th one (a maths.ox.ac.uk. nameserver), but there isn’t in this case.

jvns.ca only involves 3 nameservers:

- the

.nameserver - the

ca.nameserver - the

jvns.ca.nameserver

real DNS resolvers actually make more queries than this

When my resolver resolves reddit.com., it only makes 3 DNS queries.

$ go run resolve.go reddit.com.

dig -r @198.41.0.4 reddit.com.

e.gtld-servers.net. 172800 IN A 192.12.94.30

dig -r @192.12.94.30 reddit.com.

ns-378.awsdns-47.com. 172800 IN A 205.251.193.122

dig -r @205.251.193.122 reddit.com.

reddit.com. 300 IN A 151.101.129.140

Result: 151.101.129.140

But when unbound (the actual DNS resolver that I have running on my laptop)

resolves reddit.com, it makes more DNS queries. I captured them with tcpdump

to see what they were.

This tcpdump output might be a little illegible because well, that’s how

tcpdump is, but hopefully it makes some sense.

Unbound skips the first step, because it has the address of the com.

nameserver cached. Then the next 2 queries unbound makes are exactly the

same as my tiny Go resolver, except that it sends its first query to

k.gtld-servers.net instead of e.gtld-servers.net:

12:38:35.479222 wlp3s0 Out IP pomegranate.19946 > k.gtld-servers.net.domain: 51686% [1au] A? reddit.com. (39)

12:38:35.757033 wlp3s0 Out IP pomegranate.29111 > ns-378.awsdns-47.com.domain: 8859% [1au] A? reddit.com. (39)

But then it keeps making DNS queries, even after it’s done resolving reddit.com:

12:38:35.757033 wlp3s0 Out IP pomegranate.29111 > ns-378.awsdns-47.com.domain: 8859% [1au] A? reddit.com. (39)

12:38:35.757396 wlp3s0 Out IP pomegranate.31913 > ns-1775.awsdns-29.co.uk.domain: 54236% [1au] A? ns-378.awsdns-47.com. (49)

12:38:35.757761 wlp3s0 Out IP pomegranate.62059 > g.gtld-servers.net.domain: 28793% [1au] A? awsdns-05.net. (42)

12:38:35.757955 wlp3s0 Out IP pomegranate.34743 > b0.org.afilias-nst.org.domain: 24975% [1au] A? awsdns-00.org. (42)

12:38:35.758051 wlp3s0 Out IP pomegranate.8977 > a0.org.afilias-nst.info.domain: 53387% [1au] A? awsdns-00.org. (42)

12:38:35.758285 wlp3s0 Out IP pomegranate.11376 > j.gtld-servers.net.domain: 41181% [1au] A? awsdns-05.net. (42)

12:38:35.775497 wlp3s0 In IP ns-378.awsdns-47.com.domain > pomegranate.29111: 8859*-$ 4/4/1 A 151.101.1.140, A 151.101.129.140, A 151.101.65.140, A 151.101.193.140 (240)

12:38:35.775948 lo In IP localhost.domain > localhost.34429: 4033 4/0/1 A 151.101.1.140, A 151.101.129.140, A 151.101.65.140, A 151.101.193.140 (103)

# now it's done -- it returned its DNS response!

# but it keeps making queries about reddit.com's nameservers...

12:38:35.843811 wlp3s0 Out IP pomegranate.44738 > ns-706.awsdns-24.net.domain: 14817% [1au] A? ns-1029.awsdns-00.org. (50)

12:38:35.845563 wlp3s0 Out IP pomegranate.55655 > ns-1027.awsdns-00.org.domain: 3120% [1au] A? ns-1029.awsdns-00.org. (50)

12:38:36.017618 wlp3s0 Out IP pomegranate.53397 > ns-775.awsdns-32.net.domain: 32671% [1au] A? ns-557.awsdns-05.net. (49)

12:38:36.045151 wlp3s0 Out IP pomegranate.40525 > ns-454.awsdns-56.com.domain: 20823% [1au] A? ns-557.awsdns-05.net. (49)

So that’s kind of interesting. I guess it makes sense that unbound would want to cache more nameserver addresses in case it needs them in the future. Or maybe that’s what the DNS specification says to do?

is this a “recursive” program?

DNS resolvers are often called “recursive nameservers”. I’ve stopped using that

terminology myself in explanations, but as far as I can tell, this is because

the resolve function is often a recursive function.

And the resolve function I wrote is definitely recursive! But I ran this

program on 500 different domains, and these are the number of times it

recursed:

- Sometimes 0 times (the function never calls itself)

- Sometimes 1 time (the function calls itself once, to look up the IP address of one nameserver)

- Very rarely 2 times (like for example to resolve

abc.net.au.right now it needs to look upr.au., theneur2.akam.net.thenabc.net.au.) - So far, never 3 times

Maybe there’s a domain that this function would recurse more than 2 times on, but I don’t know.

You definitely could write this program in a way that recurses more, by replacing the loop with more recursion. And then it would recurse 3 or 6 or 7 or 9 times, depending on the domain. But to me the loop feels easier to read so I wrote it with a loop instead.

a bash version of this resolver

I wanted to see if it was possible to write a DNS resolver in 10-15 lines of bash, similarly to this short “run a container” script

The program I came up with was kind of too long in the end (it’s about 36 lines), but here it is anyway. It uses the exact same algorithm as the Go program.

https://github.com/jvns/tiny-resolver/blob/main/resolver.sh

The bash version is even more janky and uses grep in very questionable ways

but it did resolve every domain I tried which is cool.

It actually helped me write the Go resolver (which I actually started back in November but got stuck on) because bash’s limitations forced me to simplify the design and simplifying it fixed a bug I was running into.

how is this different from a “real” DNS resolver?

Obviously this is only 80 lines so there are a lot of differences between this an a “real” DNS resolver. Here are a few:

- it only handles A records, not other record types

- specifically it doesn’t handle CNAME records (though you can easily add CNAME support with just another 12 lines of code)

- it always only returns one A record even if there are more

- it has absolutely no ability to handle errors like “there were no A records” (the Go program just panics)

- the way it handles the glue records is a bit sketchy, probably it should check that they match the nameservers in the “Authority” section or something. It seems to work though.

- DNS resolvers are usually servers, this is a command line program

- it doesn’t validate DNSSEC or whatever

- it doesn’t do caching

- it doesn’t try a different nameserver if one of the domain’s nameservers isn’t working and times out the DNS query

- like we mentioned above, unbound seems to look up the addresses of all the nameservers for a domain

- probably there are other bugs and ways it violates the DNS spec that I don’t know about

tiny versions of real programs are fun

As usual I always learn something from writing tiny versions of real programs. I’ve written this program before but I think this version is better than the first version I wrote.

In 2020 I ran a 2-day workshop with my friend Allison called “Domain Name

Saturday” where all the participants wrote DNS resolvers. Basically the idea

was that you implement the algorithm described in this post, as well as the

binary parsing pieces that the miekg/dns library handles here. At some point

I want to write up that workshop so that other people could run it, because it

was really fun.

One question I still have is – are there domains where the resolve function

would recurse 3 times or more on? Obviously you could manufacture such a domain

by making it intentionally have to go through a bunch of hoops, but.. do they

exist in the real world?