Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

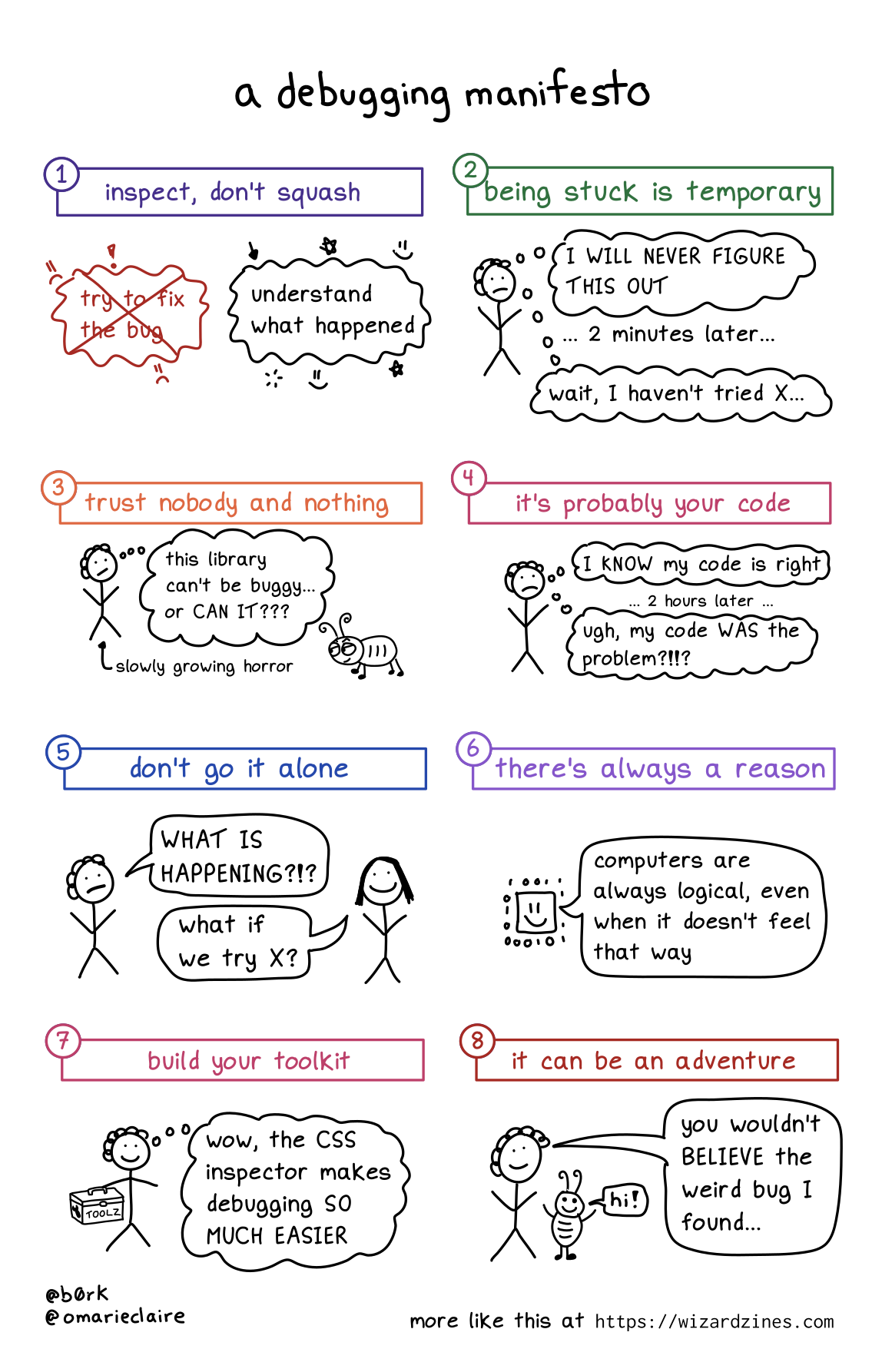

A debugging manifesto

Hello! I’ve been working on a zine about debugging for the last 6 months with my friend Marie, and one of the problems we ran into was figuring out how to explain the right attitude to take when debugging.

We ended up writing a short debugging manifesto to start the zine with, and I’m pretty happy with how it came out. Here it is as an image, and as text (with some extra explanations)

1. Inspect, don’t squash

When you run into a bug, the natural instinct is to try to fix it as fast as possible. And of course, sometimes that’s what you have to do – if the bug is causing a huge production incident, you have to mitigate it quickly before diving into figuring out the root cause.

But in my day to day debugging, I find that it’s generally more effective (and faster!) to leave the bug in place, figure out exactly what’s gone wrong, and then fix it after I’ve understood what happened.

Trying to fix it or add workarounds without fully understanding what happened usually ends up just leaving me more confused.

2. Being stuck is temporary

Sometimes I get really demoralized when debugging and it feels like I’ll NEVER make progress.

I have to remind myself that I’ve fixed a lot of bugs before, and I’ll probably fix this one too :)

3. Trust nobody and nothing

Sometimes bugs come from surprising sources! For example, in I think I found a Mac kernel bug? I describe how, the first time I tried to write a program for Mac OS, I had a bug in my program that was caused by a Mac OS kernel bug.

This was really surprising (usually the operating system is not at fault!!), but sometimes even normally-trustworthy sources are wrong. Even it’s a popular library, your operating system, the official documentation, or an extremely smart and competent coworker!

4. It’s probably your code

That said, almost all of the time the problem is not “there’s a bug in Mac OS”. I can only speak for myself, but 95% of the time something is going wrong with my program, it’s because I did something silly.

So it’s important to look for the problem in your own code first before trying to blame some external source.

5. Don’t go it alone

I’ve learned SO much by asking coworkers or friends for help with debugging. I think it’s one of the most fun ways to collaborate because you have a specific goal, and there are tons of opportunities to share information like:

- how to use a specific debugging tool (“here’s how to use GDB to inspect the memory here….”)

- how a computer thing works (“hey, can you explain CORS?”)

- similar past bugs (“I’ve seen this break in X way in the past, maybe it’s that?”)

6. There’s always a reason

This one kind of speaks for itself: sometimes it feels like things are just randomly breaking for no reason, but that’s never true.

Even if something truly weird is happening (like a hardware problem), that’s still a reason.

7. Build your toolkit

I’ve written a LOT about my love for debugging tools like tcpdump, strace, and more on this blog.

To fix bugs you need information about what your program is doing, and to get that information sometimes you need to learn a new tool.

Also, sometimes you need to build your own better tools, like by improving your test suite, pretty printing, etc.

8. It can be an adventure

As you probably know if you’re a regular reader of this blog, I love debugging and I’ve learned a lot from doing it. You get to learn something new! Sometimes you get a great war story to tell! What could be more fun?

I really think of debugging as an investment in my future knowledge – if something is breaking, it’s often because there’s something wrong in my mental model, and that’s an opportunity to learn and make sure that I know it for next time.

Of course, not all bugs are adventures (that off-by-one error I was debugging today certainly did not feel like a fun adventure). But I think it’s important to (as much as you can) reflect on your bugs and see what you can learn from them.

Tips for analyzing logs

Hello! I’ve been working on writing a zine about debugging for a while now (we’re getting close to finishing it!!!!), and one of the pages is about analyzing logs. I asked for some tips on Mastodon and got WAY more tips than could fit on the page, so I thought I’d write a quick blog post.

I’m going to talk about log analysis in the context of distributed systems debugging (you have a bunch of servers with different log files and you need to work out what happened) since that’s what I’m most familiar with.

search for the request’s ID

Often log lines will include a request ID. So searching for the request ID of a failed reques will show all the log lines for that request.

This is a GREAT way to cut things down, and it’s one of the first helpful tips I got about distributed systems debugging – I was staring at a bunch of graphs on a dashboard fruitlessly trying to find patterns, and a coworker gave me the advice (“julia, try looking at the logs for a failed request instead!”). That turned out to be WAY more effective in that case.

correlate between different systems

Sometimes one set of logs doesn’t have the information you need, but you can get that information from a different service’s logs about the same request.

If you’re lucky, they’ll both share a request ID.

More often, you’ll need to manually piece together context from clues and the timestamps of the request.

This is really annoying but I’ve found that often it’s worth it and gets me a key piece of information.

beware of time issues

If you’re trying to correlate events based on time, there are a couple of things to be aware of:

- sometimes the time in a logging system is based on the time the log was ingested, not the time that the event actually happened. Sometimes you have to write a date parser to get the actual time the event happened.

- different machines can have slightly skewed clocks

log lines for the same request can be very far apart

Especially if a request takes a long time (maybe it took 5 minutes because of a long timeout!), the log lines for the request might be much more spread out than you expected. You can accumulate many thousands of log lines in 5 minutes!

Searching for the request ID really helps with this – it makes it harder to accidentally miss a log entry with an important clue.

Also, log lines can occasionally get completely lost if a server dies.

build a timeline

Keeping all of the information straight in your head can get VERY confusing, so I find it helpful to keep a debugging document where I copy and paste bits of information.

This might include:

- key error messages

- links to relevant dashboards / log system searches

- pager alerts

- graphs

- human actions that were taken (“right before this message, we restarted the load balancer…”)

- my interpretation of various messages (“I think this was caused by…”)

reformat them into a table

Sometimes I’ll reformat the log lines to just print out the information I’m

interested in, to make it easier to scan. I’ve done this on the command line

with a simple awk command:

cat ... | awk '{print $5 - $8}'

but also with fancy log analysis tools (like Splunk) that let you make a table on the web

check that a “suspicious” error is actually new

Sometimes I’ll notice a suspicious error in the logs and think “OH THERE’S THE CULPRIT!!!“. But when I search for that message to make sure that it’s actually new, I’ll find out that this error actually happens constantly during normal operation, and that it’s completely unrelated to the (new) situation that I’m dealing with.

use the logs to make a graph

Some log analysis tools will let you turn your log lines into a graph to detect patterns.

You can also make a quick histogram with grep and sort. For example I’ve

often done something like:

grep -o (some regex) | sort | uniq -c | sort -n

to count how many of each line matching my regular expression there are

filter out irrelevant lines

You can remove irrelevant lines with grep like this:

cat file | grep -v THING1 | grep -v THING2 | grep -v THING3 | grep -v THING4

for the reply guys: yes, we all know you don’t need to use cat here :)

Or if your log system has some kind of query language, you can search for NOT THING1 AND NOT THING2 ...

find the first error

Often an error causes a huge cascade of related errors. Digging into the later errors can waste a lot of your time – you need to start by finding the first thing that triggered the error. Often you don’t need to understand the exact deals of why the 15th thing in the error cascade failed, you can just fix the original problem and move on.

scroll through the log really fast

If you already have an intuition for what log lines for this service should normally look like, sometimes scrolling through them really fast will reveal something that looks off.

turn the log level up (or down)

Sometimes turning up the log level will give you a key error message that explains everything.

But other times, you’ll get overwhelmed by a million irrelevant messages

because the log level is set to INFO, and you need to turn the log level down.

put it in a spreadsheet/database

I’ve never tried this myself, but a couple of people suggested copying parts of the logs into a spreadsheet (with the timestamp in a different column) to make it easier to filter / sort.

You could also put the data into SQLite or something (maybe with sqlite-utils?) if you want to be able to run SQL queries on your logs.

on generating good logs

A bunch of people also had thoughts on how to output easier-to-analyze logs. This is a bigger topic than a few bullet points but here are a few quick things:

- use a standard schema/format to make them easier to parse

- include a transaction ID/request ID, to make it easier to filter for all lines related to a single transaction/request

- include relevant information. For example, “ERROR: Invalid msg size” is less helpful than “ERROR: Invalid msg size. Msg-id 234, expected size 54, received size 0”.

- avoid logging personally identifiable information

- use a logging framework instead of using

printstatements (this helps you have things like log levels and a standard structure)

that’s all!

Let me know on Twitter/Mastodon if there’s anything I missed! I might edit this to add a couple more things.

A couple of Rust error messages

Hello!

I’ve been doing Advent of Code in Rust for the past couple of days, because I’ve never really gotten comfortable with the language and I thought doing some Advent of Code problems might help.

My solutions aren’t anything special, but because I’m trying to learn, I’ve been trying to take a slightly more rigorous approach than usual to compiler errors. Instead of just fixing the error and moving on, I’m trying to make sure that I actually understand what the error message means and what it’s telling me about how the language works.

My steps to do that are:

- fix the bug

- make a tiny standalone program reproducing the same compiler error

- think about it and try to explain it to myself to make sure I actually understand why that error happened

- ask for help if I still don’t understand

So here are a couple of compiler errors and my explanations to myself of why the error is happening.

Both of them are pretty basic Rust errors, but I had fun thinking about them today. I wrote this for an imagined audience of “people who know some Rust basics but are still pretty bad at Rust”, if there are any of you out there.

error 1: a borrowing error

Here’s some code (rust playground link):

fn inputs() -> Vec<(i32, i32)> {

return vec![(0, 0)];

}

fn main() {

let scores = inputs().iter().map(|(a, b)| {

a + b

});

println!("{}", scores.sum::<i32>());

}

And here’s the compiler error:

5 | let scores = inputs().iter().map(|(a, b)| {

| ^^^^^^^^ creates a temporary which is freed while still in use

6 | a + b

7 | });

| - temporary value is freed at the end of this statement

8 | println!("{}", scores.sum::<i32>());

| ------ borrow later used here

help: consider using a `let` binding to create a longer lived value

|

5 ~ let binding = inputs();

6 ~ let scores = binding.iter().map(|(a, b)| {

|

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0716`.

This is a pretty basic Rust error message about borrowing, but I’ve forgotten everything about Rust so I didn’t understand it.

There are 2 things I didn’t know / wasn’t thinking about here:

thing 1: Variables are semantically meaningful in Rust.

What I mean by that is that this code:

let scores = inputs().iter().map(|(a, b)| { ... };

does not do the same thing as if we factor out inputs() into a variable, in this code:

let input = inputs();

let scores = input.iter().map(|(a, b)| { ... };

If some memory is allocated and it isn’t in its own variable, then it’s freed

at the end of the expression (though there are some exceptions to this

apparently, see rustc --explain E0716 for more). But it does have its own

variable, then it’s kept around until the end of the block.

In the error message the Rust compiler actually suggests an explanation to read

(rustc --explain E0716), which explains all of this and more. I didn’t notice

it right away, but once I read it (and Googled a little), it really helped me.

thing 2:. Computations with iter() don’t happen right away.

This is something that I theoretically knew, but wasn’t thinking about how it might relate to compiler errors.

When I call .map(...), that doesn’t actually do the map right away – it

just sets up an iterator that can do actual calculation later, when we call

.sum().

This means that I need to keep around the memory from inputs(), because none

of the calculation has even happened yet!

error 2: summing an Iterator<()>

Here’s some code (rust playground link) (This isn’t the actual code I was debugging, but it’s the fastest way to demonstrate the error message)

fn main() {

vec![(), ()].iter().sum::<i32>();

}

This has a pretty obvious bug: You can’t sum a bunch of () (the empty type)

and get an i32 as a result. Here’s the compiler error, though:

2 | vec![(), ()].iter().sum::<i32>();

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ --- required by a bound introduced by this call

| |

| the trait `Sum<&()>` is not implemented for `i32`

This was very confusing to me – I’d expect to see an error saying something

like Sum is not implemented for Iterator<()>. But instead it says that Sum is

not implemented for i32. But I’m not trying to sum i32s! What’s going on?

What’s actually going on here is (thanks to some lovely people who helped me out!):

i32has a static method calledsum(iter: Iterator<i32>), that comes from theSumtrait. (defined here for integers)Iteratorhas asum()method that calls this static method oni32(defined here)- when I run

my_iter.sum(), it tries to calli32::sum(my_iter) - But

i32::sumisn’t defined forIterator<&()>! - The type parameter in

Sum(eg)Sum<&()>refers to the type of the iterator that’s being passed toi32::sum() - as a result, we get the error message

the trait Sum<&()> is not implemented for i32

I might not have gotten all the types/terms exactly right here, but I think that’s the gist of it.

This was a good reminder that sometimes methods (like sum() on Iterator are

defined in slightly indirect/counterintuitive ways and that you have to hunt

down the details of how it’s implemented to understand the compiler errors.

(my actual bug here was actually that I’d accidentally added an extra ; in my

code, which meant that I accidentally created an Iterator<()> instead of an

Iterator<i32>, and the confusing error message made it harder to figure out that

out)

Rust error messages are cool

I found these error messages pretty helpful, I especially really appreciated the --explain output on the borrowing error.

Making a DNS query in Ruby from scratch

Hello! A while back I wrote a post about how to write a toy DNS resolver in Go.

In that post I left out “how to generate and parse DNS queries” because I thought it was boring, but a few people pointed out that they did not know how to parse and generate DNS queries and they were interested in how to do it.

This made me curious – how much work is it do the DNS parsing? It turns out we can do it in a pretty nice 120-line Ruby program, which is not that bad.

So here’s a quick post on how to generate DNS queries and parse DNS responses! We’re going to do it in Ruby because I’m giving a talk at a Ruby conference soon, and this blog post is partly prep for that talk :). I’ve tried to keep it readable for folks who don’t know Ruby though, I’ve only used pretty basic Ruby code.

At the end we’re going to have a very simple toy Ruby version of dig that can

look up domain names like this:

$ ruby dig.rb example.com

example.com 20314 A 93.184.216.34

The whole thing is about 120 lines of code, so it’s not that much. (The final program is dig.rb if you want to skip the explanations and just read some code.) We won’t implement the “how a DNS resolver works” from the previous post because, well, we already did that. Let’s get into it!

Along the way I’m going to try to explain how you could figure out some of this stuff yourself if you were trying to figure out how DNS queries are formatted from scratch. Mostly that’s “poke around in Wireshark” and “read RFC 1035, the DNS RFC”.

step 1: open a UDP socket

We need to actually send our queries, so to do that we need to open a UDP

socket. We’ll send our queries to 8.8.8.8, Google’s DNS server.

Here’s the code to set up a UDP connection to 8.8.8.8, port 53 (the DNS port).

require 'socket'

sock = UDPSocket.new

sock.bind('0.0.0.0', 12345)

sock.connect('8.8.8.8', 53)

a quick note on UDP

I’m not going to say too much about UDP here, but I will say that the basic unit of computer networking is the “packet” (a packet is a string of bytes), and in this program we’re going to do the simplest possible thing you can do with a computer network – send 1 packet and receive 1 packet in response.

So UDP is a way to send packets in the simplest possible way.

It’s the most common way to send DNS queries, though you can also use TCP or DNS-over-HTTPS instead.

step 2: copy a DNS query from Wireshark

Next: let’s say we have no idea how DNS works but we want to send a working query as fast as possible. The easiest way to get a DNS query to play with and make sure our UDP connection is working is to just copy one that already works!

So that’s what we’re going to do, using Wireshark (an incredible packet analysis tool)

The steps I used to this are roughly:

- Open Wireshark and click ‘capture’

- Enter

udp.port == 53as a filter (in the search bar) - Run

ping example.comin my terminal (to generate a DNS query) - Click on the DNS query (“Standard query A example.com”)

- Right click on “Domain Name System (query”) in the bottom left pane

- Click ‘Copy’ -> ‘as a hex stream’

- Now I have “b96201000001000000000000076578616d706c6503636f6d0000010001” on my clipboard, to use in my Ruby program. Hooray!

step 3: decode the hex stream and send the DNS query

Now we can send our DNS query to 8.8.8.8! Here’s what that looks like: we just need to add 5 lines of code

hex_string = "b96201000001000000000000076578616d706c6503636f6d0000010001"

bytes = [hex_string].pack('H*')

sock.send(bytes, 0)

# get the reply

reply, _ = sock.recvfrom(1024)

puts reply.unpack('H*')

[hex_string].pack('H*') is translating our hex string into a byte string. At

this point we don’t really know what this data means but we’ll get there in a

second.

We can also take this opportunity to make sure our program is working and is sending valid data, using tcpdump. How I did that:

- Run

sudo tcpdump -ni any port 53 and host 8.8.8.8in a terminal tab - In a different terminal tab, run this Ruby program (

ruby dns-1.rb)

Here’s what the output looks like:

$ sudo tcpdump -ni any port 53 and host 8.8.8.8

08:50:28.287440 IP 192.168.1.174.12345 > 8.8.8.8.53: 47458+ A? example.com. (29)

08:50:28.312043 IP 8.8.8.8.53 > 192.168.1.174.12345: 47458 1/0/0 A 93.184.216.34 (45)

This is really good - we can see the DNS request (“what’s the IP for

example.com”) and the response (“it’s 93.184.216.34”). So everything is

working. Now we just need to, you know, figure out how to generate and decode this data ourselves.

step 4: learn a little about how DNS queries are formatted

Now that we have a DNS query for example.com, let’s learn about what it means.

Here’s our query, formatted as hex.

b96201000001000000000000076578616d706c6503636f6d0000010001

If you poke around in Wireshark, you’ll see that this query has 2 parts:

- The header (

b96201000001000000000000) - The question (

076578616d706c6503636f6d0000010001)

step 5: make the header

Our goal in this step is to generate the byte string

b96201000001000000000000, but with a Ruby function instead of hardcoding it.

So: the header is 12 bytes. What do those 12 bytes mean? If you look at Wireshark (or read RFC 1035), you’ll see that it’s 6 2-byte numbers concatenated together.

The 6 numbers correspond to the query ID, the flags, and then the number of questions, answer records, authoritative records, and additional records in the packet.

We don’t need to worry about what all those things are yet though – we just need to put in 6 numbers.

And luckily we know exactly which 6 numbers to put because our goal is to

literally generate the string b96201000001000000000000.

So here’s a function to make the header. (note: there’s no return because you don’t need to write return in Ruby if it’s the last line of the function)

def make_question_header(query_id)

# id, flags, num questions, num answers, num auth, num additional

[query_id, 0x0100, 0x0001, 0x0000, 0x0000, 0x0000].pack('nnnnnn')

end

This is very short because we’ve hardcoded everything except the query ID.

what’s nnnnnn?

You might be wondering what nnnnnn is in .pack('nnnnnn'). That’s a format

string telling .pack() how to convert that array of 6 numbers into a byte

string.

The documentation for .pack is here, and it says that n means

“represent it as “16-bit unsigned, network (big-endian) byte order”.

16 bits is the same as 2 bytes, and we need to use network byte order because this is computer networking. I’m not going to explain byte order right now (though I do have a comic attempting to explain it)

test the header code

Let’s quickly test that our make_question_header function works.

puts make_question_header(0xb962) == ["b96201000001000000000000"].pack("H*")

This prints out “true”, so we win and we can move on.

step 5: encode the domain name

Next we need to generate the question (“what’s the IP for example.com?“). This has 3 parts:

- the domain name (for example “example.com”)

- the query type (for example “A” is for “IPv4 Address”

- the query class (which is always the same, 1 is for IN is for INternet)

The hardest part of this is the domain name so let’s write a function to do that.

example.com is encoded in a DNS query, in hex, as 076578616d706c6503636f6d00. What does that mean?

Well, if we translate the bytes into ASCII, it looks like this:

076578616d706c6503636f6d00

7 e x a m p l e 3 c o m 0

So each segment (like example) has its length (like 7) in front of it.

Here’s the Ruby code to translate example.com into 7 e x a m p l e 3 c o m 0:

def encode_domain_name(domain)

domain

.split(".")

.map { |x| x.length.chr + x }

.join + "\0"

end

Other than that, to finish generating the question section we just need to append the type and class onto the end of the domain name.

step 6: write make_dns_query

Here’s the final function to make a DNS query:

def make_dns_query(domain, type)

query_id = rand(65535)

header = make_question_header(query_id)

question = encode_domain_name(domain) + [type, 1].pack('nn')

header + question

end

Here’s all the code we’ve written before in dns-2.rb –

it’s still only 29 lines.

now for the parsing

Now that we’ve managed to generate a DNS query, we get into the hard part: the parsing. Again, we’ll split this into a bunch of different

- parse a DNS header

- parse a DNS name

- parse a DNS record

The hardest part of this (maybe surprisingly) is going to be “parse a DNS name”.

step 7: parse the DNS header

Let’s start with the easiest part: the DNS header. We already talked about how it’s 6 numbers concatenated together.

So all we need to do is

- read the first 12 bytes

- convert that into an array of 6 numbers

- put those numbers in a class for convenience

Here’s the Ruby code to do that.

class DNSHeader

attr_reader :id, :flags, :num_questions, :num_answers, :num_auth, :num_additional

def initialize(buf)

hdr = buf.read(12)

@id, @flags, @num_questions, @num_answers, @num_auth, @num_additional = hdr.unpack('nnnnnn')

end

end

Quick Ruby note: attr_reader is a Ruby thing that means “make these instance

variables accessible as methods”. So you can call header.flags to look at the

@flags variable.

We can call this with DNSHeader(buf). Not so bad.

Let’s move on to the hardest part: parsing a domain name.

step 8: parse a domain name

First, let’s write a partial version.

def read_domain_name_wrong(buf)

domain = []

loop do

len = buf.read(1).unpack('C')[0]

break if len == 0

domain << buf.read(len)

end

domain.join('.')

end

This repeatedly reads 1 byte and then reads that length into a string until the length is 0.

This works great, for the first time we see a domain name (example.com) in our DNS response.

trouble with domain names: compression!

But the second time example.com appears, we run into trouble – in Wireshark,

it says that the domain is represented cryptically as just the 2 bytes c00c.

This is something called DNS compression and if we want to parse any DNS responses we’re going to have to implement it.

This is luckily not that hard. All c00c is saying is:

- The first 2 bits (

0b11.....) mean “DNS compression ahead!” - The remaining 14 bits are an integer. In this case that integer is

12(0x0c), so that means “go back to the 12th byte in the packet and use the domain name you find there”

If you want to read more about DNS compression, I found the explanation in the DNS RFC relatively readable.

step 9: implement DNS compression

So we need a more complicated version of our read_domain_name function

Here it is.

domain = []

loop do

len = buf.read(1).unpack('C')[0]

break if len == 0

if len & 0b11000000 == 0b11000000

# weird case: DNS compression!

second_byte = buf.read(1).unpack('C')[0]

offset = ((len & 0x3f) << 8) + second_byte

old_pos = buf.pos

buf.pos = offset

domain << read_domain_name(buf)

buf.pos = old_pos

break

else

# normal case

domain << buf.read(len)

end

end

domain.join('.')

Basically what’s happening is:

- if the first 2 bits are

0b11, we need to do DNS compression. Then:- read the second byte and do a little bit arithmetic to convert that into the offset

- save the current position in the buffer

- read the domain name at the offset we calculated

- restore our position in the buffer

This is kind of messy but it’s the most complicated part of parsing the DNS response, so we’re almost done!

a DNS compression exploit

Someone pointed out that a malicious actor could exploit this code by sending a

DNS response with a DNS compression entry that points to itself, so that

read_domain_name would end up in an infinite loop. I won’t update it (the

code is already complicated enough!) but a real DNS parser would be

smarter and deal with that. For example here’s the code that avoids infinite loops in miekg/dns

There are also probably other edge cases that would be problematic if this were a real DNS parser.

step 10: parse a DNS query

You might think “why do we need to parse a DNS query? This is the response!”. But every DNS response has the original query in it, so we need to parse it.

Here’s the code for parsing the DNS query.

class DNSQuery

attr_reader :domain, :type, :cls

def initialize(buf)

@domain = read_domain_name(buf)

@type, @cls = buf.read(4).unpack('nn')

end

end

There’s not very much to it: the type and class are 2 bytes each.

step 11: parse a DNS record

This is the exciting part – the DNS record is where our query data lives! The “rdata field” (“record data”) is where the IP address we’re going to get in response to our DNS query lives.

Here’s the code:

class DNSRecord

attr_reader :name, :type, :class, :ttl, :rdlength, :rdata

def initialize(buf)

@name = read_domain_name(buf)

@type, @class, @ttl, @rdlength = buf.read(10).unpack('nnNn')

@rdata = buf.read(@rdlength)

end

We also need to do a little work to make the rdata field human readable. The

meaning of the record data depends on the record type – for example for an

“A” record it’s a 4-byte IP address, for but a “CNAME” record it’s a domain

name.

So here’s some code to make the request data human readable:

def read_rdata(buf, length)

@type_name = TYPES[@type] || @type

if @type_name == "CNAME" or @type_name == "NS"

read_domain_name(buf)

elsif @type_name == "A"

buf.read(length).unpack('C*').join('.')

else

buf.read(length)

end

end

This function uses this TYPES hash to map the record type to a human-readable name:

TYPES = {

1 => "A",

2 => "NS",

5 => "CNAME",

# there are a lot more but we don't need them for this example

}

The most interesting part of read_rdata is probably the line buf.read(length).unpack('C*').join('.') – it’s saying “hey, an IP address is 4 bytes,

so convert it into an array of 4 numbers and then join those with “.“s”.

step 12: finish parsing the DNS response

Now we’re ready to parse the DNS response!

Here’s some code to do that:

class DNSResponse

attr_reader :header, :queries, :answers, :authorities, :additionals

def initialize(bytes)

buf = StringIO.new(bytes)

@header = DNSHeader.new(buf)

@queries = (1..@header.num_questions).map { DNSQuery.new(buf) }

@answers = (1..@header.num_answers).map { DNSRecord.new(buf) }

@authorities = (1..@header.num_auth).map { DNSRecord.new(buf) }

@additionals = (1..@header.num_additional).map { DNSRecord.new(buf) }

end

end

This mostly just calls the other functions we’ve written to parse the DNS response.

It uses this cute (1..@header.num_answers).map construction to create an

array of 2 DNS records if @header.num_answers is 2. (which is maybe a

little bit of Ruby magic but I think it’s kind of fun and hopefully isn’t too hard

to read)

We can integrate this code into our main function like this:

sock.send(make_dns_query("example.com", 1), 0) # 1 is "A", for IP address

reply, _ = sock.recvfrom(1024)

response = DNSResponse.new(reply) # parse the response!!!

puts response.answers[0]

Printing out the records looks awful though (it says something like

#<DNSRecord:0x00000001368e3118>). So we need to write some pretty printing

code to make it human readable.

step 13: pretty print our DNS records

We need to add a .to_s field to DNS records to make them have a nice string

representation. This is just a 1-line method in DNSRecord:

def to_s

"#{@name}\t\t#{@ttl}\t#{@type_name}\t#{@parsed_rdata}"

end

You also might notice that I left out the class field of the DNS record. That’s because it’s

always the same (IN for “internet”) so I felt it was redundant. Most DNS tools

(like real dig) will print out the class though.

and we’re done!

Here’s our final main function:

def main

# connect to google dns

sock = UDPSocket.new

sock.bind('0.0.0.0', 0)

sock.connect('8.8.8.8', 53)

# send query

domain = ARGV[0]

sock.send(make_dns_query(domain, 1), 0)

# receive & parse response

reply, _ = sock.recvfrom(1024)

response = DNSResponse.new(reply)

response.answers.each do |record|

puts record

end

I don’t think there’s too much to say about this – we connect, send a query, print out each of the answers, and exit. Success!

$ ruby dig.rb example.com

example.com 18608 A 93.184.216.34

You can see the final program as a gist here: dig.rb. You could add more features to it if you want, like

- pretty printing for other query types

- options to print out the “authority” and “additional” sections of the DNS response

- retries

- making sure that the DNS response we see is actually a response to the query we sent (the query ID has to match!

Also you can let me know on Twitter if I’ve made a mistake in this post somewhere – I wrote this pretty quickly so I probably got something wrong.

Why do domain names sometimes end with a dot?

Hello! When I was writing the zine How DNS Works

earlier this year, someone asked me – why do people sometimes put a dot at the

end of a domain name? For example, if you look up the IP for example.com by

running dig example.com, you’ll see this:

$ dig example.com

example.com. 5678 IN A 93.184.216.34

dig has put a . to the end of example.com – now it’s example.com.! What’s up with that?

Also, some DNS tools require domains to have a "." at the end: if you try to pass example.com to miekg/dns, like this, it’ll fail:

// trying to send this message will return an error

m := new(dns.Msg)

m.SetQuestion("example.com", dns.TypeA)

Originally I thought I knew the answer to this (“uh, the dot at the end means the domain is fully qualified?“). And that’s true – a fully qualified domain name is a domain with a “.” at the end!

But that doesn’t explain why dots at the end are useful or important.

in a DNS request/response, domain names don’t have a trailing “.”

I once (incorrectly) thought the answer to “why is there a dot at the end?” might be “In a DNS request/response, domain names have a “.” at the end, so we put it in to match what actually gets sent/received by your computer”. But that’s not true at all!

When a computer sends a DNS request or response, the domain names in it don’t have a trailing dot. Actually, the domain names don’t have any dots.

Instead, they’re encoded as a series of length/string pairs. For example,

the domain example.com is encoded as these 13 bytes:

7example3com0

So there are no dots at all. Instead, an ASCII domain name (like “example.com”) gets translated into the format used in a DNS request / response by various DNS software.

So let’s talk about one place where domain names are translated into DNS responses: zone files.

the trailing “.” in zone files

One way that some people manage DNS records for a domain is to create a text

file called a “zone file” and then configure some DNS server software (like nsd

or bind) to serve the DNS records specified in that zone file.

Here’s an imaginary zone file for example.com:

orange 300 IN A 1.2.3.4

fruit 300 IN CNAME orange

grape 3000 IN CNAME example.com.

In this zone file, anything that doesn’t end in a "." (like "orange") gets

.example.com added to it. So "orange" is shorthand for

"orange.example.com". The DNS server knows from its configuration that this

is a zone file for example.com, so it knows to automatically append

example.com at the end of any name that doesn’t end with a dot.

I assume the idea here is just to save typing – you could imagine writing this zone file by fully typing out all of the domain names:

orange.example.com. 300 IN A 1.2.3.4

fruit.example.com. 300 IN CNAME orange.example.com.

grape.example.com. 3000 IN CNAME example.com.

But that’s a lot of typing.

you don’t need zone files to use DNS

Even though the zone file format is defined in the official DNS RFC (RFC 1035), you don’t have to use zone files at all to use DNS. For example, AWS Route 53 doesn’t use zone files to store DNS records! Instead you create records through the web interface or API, and I assume they store records in some kind of database and not a bunch of text files.

Route 53 (like many other DNS tools) does support importing and exporting zone files though and it can be a good way to migrate records from one DNS provider to another.

the trailing “.” in dig

Now, let’s talk about dig’s output:

$ dig example.com

; <<>> DiG 9.18.1-1ubuntu1.1-Ubuntu <<>> +all example.com

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 10712

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 1, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 65494

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;example.com. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

example.com. 81239 IN A 93.184.216.34

One weird thing about this is that almost every line starts with a ;;. What’s

up with that? Well ; is the comment character in zone files!

So I think the reason that dig prints out its output in this weird way is so that if you wanted, you could just paste this into a zone file and have it work without any changes.

This also explains why there’s a . at the end of example.com. – zone files

require a trailing dot at the end of a domain name (because otherwise they’re

interpreted as being relative to the zone). So dig does too.

I really wish dig had a +human flag that printed out all of this information

in a more human readable way, but for now I’m too lazy to put in the work to

actually contribute code to do that (and I’m a pretty bad C programmer) so I’ll

just complain about it on my blog instead :)

the trailing "." in curl

Let’s talk about another case where the trailing "." shows up: curl!

One of the computers in my house is called “grapefruit”, and it’s running a

webserver. Here’s what happens if I run curl grapefruit:

$ curl grapefruit

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/strict.dtd">

<html>

<head>

It works! Cool. But what happens if I add a . at the end? Suddenly it doesn’t work:

$ curl grapefruit.

curl: (6) Could not resolve host: grapefruit.

What’s going on? To understand, we need to learn about search domains:

meet search domains

When I run curl grapefrult, how does that get translated into a DNS request?

You might think that my computer would send a request for the domain

grapefruit, right? But that’s not true.

Let’s use tcpdump to see what domain is actually being looked up:

$ sudo tcpdump -i any port 53

[...] A? grapefruit.lan. (32)

It’s actually sending a request for grapefruit.lan. What’s up with that?

Well, what’s going on is that:

- To look up

grapefruit,curlcalls a function calledgetaddrinfo getaddrinfolooks in a file on my computer called/etc/resolv.conf/etc/resolv.confcontains these 2 lines:nameserver 127.0.0.53 search lan

- Because it sees

search lan,getaddrinfoadds alanat the end ofgrapefruitand looks upgrapefruit.laninstead

when are search domains used?

Now we know something weird: that when we look up a domain, sometimes an extra

thing (like lan) will be added to the end. But when does that happen?

- If we put a

"."at the end of the domain (likecurl grapefruit., then search domains aren’t used - If the domain has an

"."inside it (likeexample.comhas a dot in it), then by default search domains aren’t used either. But this can be changed with configuration (see this blog post about ndots that talks about this more)

So now we know why curl grapefruit. has different results than curl grapefruit – it’s because one looks up the domain grapefruit. and the other one looks up grapefruit.lan.

how does my computer know what search domain to use?

When I connect to my router, it tells me that its search domain is lan with

DHCP – it’s the same way that my computer gets assigned an IP address.

so why do people put a dot at the end of domain names?

Now that we know about zone files and search domains, here’s why I think people like to put dots at the end of a domain name.

There are two contexts where domain names are modified and get something else added to the end:

- in a zone file for

example.com,grapefruitget translated tograpefruit.example.com - on my local network (with my computer configured to use the search domain

lan),grapefruitgets translated tograpefruit.lan

So because domain names can actually be translated to something else in some

cases, people like to put a "." at the end to communicate “THIS IS THE

DOMAIN NAME, NOTHING GETS ADDED AT THE END, THIS IS THE WHOLE THING”. Because

otherwise it can get confusing.

The technical term for “THIS IS THE WHOLE THING” is “fully qualified domain

name” or “FQDN”. So google.com. is a fully qualified domain name, and

google.com isn’t.

I always have to remind myself for the reasons for this because I rarely use

zone files or search domains, so I often feel like – “of course I mean

google.com and not google.com.something.else! Why would I mean anything

else?? That’s silly!”

But some people do use zone files and search domains (search domains are used in Kubernetes, for example!), so the “.” at the end is useful to make it 100% clear that nothing else should be added.

when to put a “.” at the end?

Here are a couple of quick notes about when to put a “.” at the end of your domain names:

Yes: when configuring DNS

It’s never bad to use fully qualified domain names when configuring DNS. You don’t always have to: a non-fully-qualified domain name will often work just fine as well, but I’ve never met a piece of DNS software that wouldn’t accept a fully qualified domain name.

And some DNS software requires it: right now the DNS server I use for jvns.ca

makes me put a "." at the end of domains names (for example in CNAME records)

and warns me otherwise it’ll append .jvns.ca to whatever I typed in. I don’t

agree with this design decision but it’s not a big deal, I just put a “.” at

the end.

No: in a browser

Confusingly, it often doesn’t work to put a "." at the end of a domain name in a

browser! For example, if I type https://twitter.com. into my browser, it

doesn’t work! It gives me a 404.

I think what’s going on here is that it’s setting the HTTP Host header to

Host: twitter.com. and the web server on the other end is expecting Host: twitter.com.

Similarly, https://jvns.ca. gives me an SSL error for some reason.

I think relative domain names used to be more common

One last thing: I think that “relative” domain names (like me using

grapefruit to refer to the other computer in my house, grapefruit.lan) used

to be more commonly used, because DNS was developed in the context of

universities or other big institutions which have big internal networks.

On the internet today, it seems like it’s more common to use “absolute” domain

names (like example.com).