Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

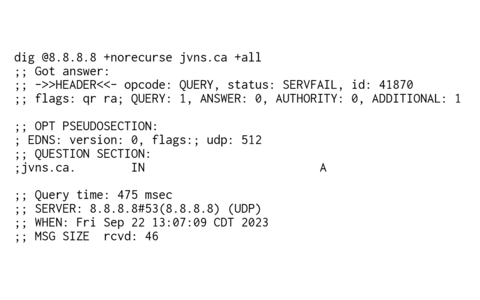

git rebase: what can go wrong?

Hello! While talking with folks about Git, I’ve been seeing a comment over and over to the effect of “I hate rebase”. People seemed to feel pretty strongly about this, and I was really surprised because I don’t run into a lot of problems with rebase and I use it all the time.

I’ve found that if many people have a very strong opinion that’s different from mine, usually it’s because they have different experiences around that thing from me.

So I asked on Mastodon:

today I’m thinking about the tradeoffs of using

git rebasea bit. I think the goal of rebase is to have a nice linear commit history, which is something I like.but what are the costs of using rebase? what problems has it caused for you in practice? I’m really only interested in specific bad experiences you’ve had here – not opinions or general statements like “rewriting history is bad”

I got a huge number of incredible answers to this, and I’m going to do my best to summarize them here. I’ll also mention solutions or workarounds to those problems in cases where I know of a solution. Here’s the list:

- fixing the same conflict repeatedly is annoying

- rebasing a lot of commits is hard

- undoing a rebase is hard

- force pushing to shared branches can cause lost work

- force pushing makes code reviews harder

- losing commit metadata

- more difficult reverts

- rebasing can break intermediate commits

- accidentally run git commit –amend instead of git rebase –continue

- splitting commits in an interactive rebase is hard

- complex rebases are hard

- rebasing long lived branches can be annoying

- rebase and commit discipline

- a “squash and merge” workflow

- miscellaneous problems

My goal with this isn’t to convince anyone that rebase is bad and you shouldn’t use it (I’m certainly going to keep using rebase!). But seeing all these problems made me want to be more cautious about recommending rebase to newcomers without explaining how to use it safely. It also makes me wonder if there’s an easier workflow for cleaning up your commit history that’s harder to accidentally mess up.

my git workflow assumptions

First, I know that people use a lot of different Git workflows. I’m going to be talking about the workflow I’m used to when working on a team, which is:

- the team uses a central Github/Gitlab repo to coordinate

- there’s one central

mainbranch. It’s protected from force pushes. - people write code in feature branches and make pull requests to

main - The web service is deployed from

mainevery time a pull request is merged. - the only way to make a change to

mainis by making a pull request on Github/Gitlab and merging it

This is not the only “correct” git workflow (it’s a very “we run a web service” workflow and open source project or desktop software with releases generally use a slightly different workflow). But it’s what I know so that’s what I’ll talk about.

two kinds of rebase

Also before we start: one big thing I noticed is that there were 2 different kinds of rebase that kept coming up, and only one of them requires you to deal with merge conflicts.

- rebasing on an ancestor, like

git rebase -i HEAD^^^^^^^to squash many small commits into one. As long as you’re just squashing commits, you’ll never have to resolve a merge conflict while doing this. - rebasing onto a branch that has diverged, like

git rebase main. This can cause merge conflicts.

I think it’s useful to make this distinction because sometimes I’m thinking about rebase type 1 (which is a lot less likely to cause problems), but people who are struggling with it are thinking about rebase type 2.

Now let’s move on to all the problems!

fixing the same conflict repeatedly is annoying

If you make many tiny commits, sometimes you end up in a hellish loop where you have to fix the same merge conflict 10 times. You can also end up fixing merge conflicts totally unnecessarily (like dealing with a merge conflict in code that a future commit deletes).

There are a few ways to make this better:

- first do a

git rebase -i HEAD^^^^^^^^^^^to squash all of the tiny commits into 1 big commit and then agit rebase mainto rebase onto a different branch. Then you only have to fix the conflicts once. - use

git rerereto automate repeatedly resolving the same merge conflicts (“rerere” stands for “reuse recorded resolution”, it’ll record your previous merge conflict resolutions and replay them). I’ve never tried this but I think you need to setgit config rerere.enabled trueand then it’ll automatically help you.

Also if I find myself resolving merge conflicts more than once in a rebase,

I’ll usually run git rebase --abort to stop it and then squash my commits into

one and try again.

rebasing a lot of commits is hard

Generally when I’m doing a rebase onto a different branch, I’m rebasing 1-2 commits. Maybe sometimes 5! Usually there are no conflicts and it works fine.

Some people described rebasing hundreds of commits by many different people onto a different branch. That sounds really difficult and I don’t envy that task.

undoing a rebase is hard

I heard from several people that when they were new to rebase, they messed up a rebase and permanently lost a week of work that they then had to redo.

The problem here is that undoing a rebase that went wrong is much more complicated

than undoing a merge that went wrong (you can undo a bad merge with something like git reset --hard HEAD^).

Many newcomers to rebase don’t even realize that undoing a rebase is even

possible, and I think it’s pretty easy to understand why.

That said, it is possible to undo a rebase that went wrong. Here’s an example of how to undo a rebase using git reflog.

step 1: Do a bad rebase (for example run git rebase -I HEAD^^^^^ and just delete 3 commits)

step 2: Run git reflog. You should see something like this:

ee244c4 (HEAD -> main) HEAD@{0}: rebase (finish): returning to refs/heads/main

ee244c4 (HEAD -> main) HEAD@{1}: rebase (pick): test

fdb8d73 HEAD@{2}: rebase (start): checkout HEAD^^^^^^^

ca7fe25 HEAD@{3}: commit: 16 bits by default

073bc72 HEAD@{4}: commit: only show tooltips on desktop

step 3: Find the entry immediately before rebase (start). In my case that’s ca7fe25

step 4: Run git reset --hard ca7fe25

A couple of other ways to undo a rebase:

- Apparently

@always refers to your current branch in git, so you can rungit reset --hard @{1}to reset your branch to its previous location. - Another solution folks mentioned that avoids having to use the reflog is to

make a “backup branch” with

git switch -c backupbefore rebasing, so you can easily get back to the old commit.

force pushing to shared branches can cause lost work

A few people mentioned the following situation:

- You’re collaborating on a branch with someone

- You push some changes

- They rebase the branch and run

git push --force(maybe by accident) - Now when you run

git pull, it’s a mess – you get the afatal: Need to specify how to reconcile divergent brancheserror - While trying to deal with the fallout you might lose some commits, especially if some of the people are involved aren’t very comfortable with git

This is an even worse situation than the “undoing a rebase is hard” situation because the missing commits might be split across many different people’s and the only worse thing than having to hunt through the reflog is multiple different people having to hunt through the reflog.

This has never happened to me because the only branch I’ve ever collaborated on

is main, and main has always been protected from force pushing (in my

experience the only way you can get something into main is through a pull

request). So I’ve never even really been in a situation where this could

happen. But I can definitely see how this would cause problems.

The main tools I know to avoid this are:

- don’t rebase on shared branches

- use

--force-with-leasewhen force pushing, to make sure that nobody else has pushed to the branch since your last fetch

Apparently the “since your last fetch” is important here – if you run git

fetch immediately before running git push --force-with-lease, the

--force-with-lease won’t protect you at all.

I was curious about why people would run git push --force on a shared branch. Some reasons people gave were:

- they’re working on a collaborative feature branch, and the feature branch needs to be rebased onto

main. The idea here is that you’re just really careful about coordinating the rebase so nothing gets lost. - as an open source maintainer, sometimes they need to rebase a contributor’s branch to fix a merge conflict

- they’re new to git, read some instructions online that suggested

git rebaseandgit push --forceas a solution, and followed them without understanding the consequences - they’re used to doing

git push --forceon a personal branch and ran it on a shared branch by accident

force pushing makes code reviews harder

The situation here is:

- You make a pull request on GitHub

- People leave some comments

- You update the code to address the comments, rebase to clean up your commits, and force push

- Now when the reviewer comes back, it’s hard for them to tell what you changed since the last time you saw it – all the commits show up as “new”.

One way to avoid this is to push new commits addressing the review comments, and then after the PR is approved do a rebase to reorganize everything.

I think some reviewers are more annoyed by this problem than others, it’s kind of a personal preference. Also this might be a Github-specific issue, other code review tools might have better tools for managing this.

losing commit metadata

If you’re rebasing to squash commits, you can lose important commit metadata

like Co-Authored-By. Also if you GPG sign your commits, rebase loses the

signatures.

There’s probably other commit metadata that you can lose that I’m not thinking of.

I haven’t run into this one so I’m not sure how to avoid it. I think GPG signing commits isn’t as popular as it used to be.

more difficult reverts

Someone mentioned that it’s important for them to be able to easily revert merging any branch (in case the branch broke something), and if the branch contains multiple commits and was merged with rebase, then you need to do multiple reverts to undo the commits.

In a merge workflow, I think you can revert merging any branch just by reverting the merge commit.

rebasing can break intermediate commits

If you’re trying to have a very clean commit history where the tests pass on every commit (very admirable!), rebasing can result in some intermediate commits that are broken and don’t pass the tests, even if the final commit passes the tests.

Apparently you can avoid this by using git rebase -x to run the test suite at

every step of the rebase and make sure that the tests are still passing. I’ve

never done that though.

accidentally run git commit --amend instead of git rebase --continue

A couple of people mentioned issues with running git commit --amend instead of git rebase --continue when resolving a merge conflict.

The reason this is confusing is that there are two reasons when you might want to edit files during a rebase:

- editing a commit (by using

editingit rebase -i), where you need to writegit commit --amendwhen you’re done - a merge conflict, where you need to run

git rebase --continuewhen you’re done

It’s very easy to get these two cases mixed up because they feel very similar. I think what goes wrong here is that you:

- Start a rebase

- Run into a merge conflict

- Resolve the merge conflict, and run

git add file.txt - Run

git commitbecause that’s what you’re used to doing after you rungit add - But you were supposed to run

git rebase --continue! Now you have a weird extra commit, and maybe it has the wrong commit message and/or author

splitting commits in an interactive rebase is hard

The whole point of rebase is to clean up your commit history, and combining

commits with rebase is pretty easy. But what if you want to split up a commit into 2

smaller commits? It’s not as easy, especially if the commit you want to split

is a few commits back! I actually don’t really know how to do it even though I

feel very comfortable with rebase. I’d probably just do git reset HEAD^^^ or

something and use git add -p to redo all my commits from scratch.

One person shared their workflow for splitting commits with rebase.

complex rebases are hard

If you try to do too many things in a single git rebase -i (reorder commits

AND combine commits AND modify a commit), it can get really confusing.

To avoid this, I personally prefer to only do 1 thing per rebase, and if I want to do 2 different things I’ll do 2 rebases.

rebasing long lived branches can be annoying

If your branch is long-lived (like for 1 month), having to rebase repeatedly gets painful. It might be easier to just do 1 merge at the end and only resolve the conflicts once.

The dream is to avoid this problem by not having long-lived branches but it doesn’t always work out that way in practice.

miscellaneous problems

A few more issues that I think are not that common:

- Stopping a rebase wrong: If you try to abort a rebase that’s going badly with

git reset --hardinstead ofgit rebase --abort, things will behave weirdly until you stop it properly - Weird interactions with merge commits: A couple of quotes about this: “If you rebase your working copy to keep a clean history for a branch, but the underlying project uses merges, the result can be ugly. If you do rebase -i HEAD~4 and the fourth commit back is a merge, you can see dozens of commits in the interactive editor.“, “I’ve learned the hard way to never rebase if I’ve merged anything from another branch”

rebase and commit discipline

I’ve seen a lot of people arguing about rebase. I’ve been thinking about why this is and I’ve noticed that people work at a few different levels of “commit discipline”:

- Literally anything goes, “wip”, “fix”, “idk”, “add thing”

- When you make a pull request (on github/gitlab), squash all of your crappy commits into a single commit with a reasonable message (usually the PR title)

- Atomic Beautiful Commits – every change is split into the appropriate number of commits, where each one has a nice commit message and where they all tell a story around the change you’re making

Often I think different people inside the same company have different levels of commit discipline, and I’ve seen people argue about this a lot. Personally I’m mostly a Level 2 person. I think Level 3 might be what people mean when they say “clean commit history”.

I think Level 1 and Level 2 are pretty easy to achieve without rebase – for

level 1, you don’t have to do anything, and for level 2, you can either press

“squash and merge” in github or run git switch main; git merge --squash mybranch on the command line.

But for Level 3, you either need rebase or some other tool (like GitUp) to help you organize your commits to tell a nice story.

I’ve been wondering if when people argue about whether people “should” use rebase or not, they’re really arguing about which minimum level of commit discipline should be required.

I think how this plays out also depends on how big the changes folks are making – if folks are usually making pretty small pull requests anyway, squashing them into 1 commit isn’t a big deal, but if you’re making a 6000-line change you probably want to split it up into multiple commits.

a “squash and merge” workflow

A couple of people mentioned using this workflow that doesn’t use rebase:

- make commits

- Run

git merge mainto merge main into the branch periodically (and fix conflicts if necessary) - When you’re done, use GitHub’s “squash and merge” feature (which is the

equivalent of running

git checkout main; git merge --squash mybranch) to squash all of the changes into 1 commit. This gets rid of all the “ugly” merge commits.

I originally thought this would make the log of commits on my branch too ugly,

but apparently git log main..mybranch will just show you the changes on your

branch, like this:

$ git log main..mybranch

756d4af (HEAD -> mybranch) Merge branch 'main' into mybranch

20106fd Merge branch 'main' into mybranch

d7da423 some commit on my branch

85a5d7d some other commit on my branch

Of course, the goal here isn’t to force people who have made beautiful atomic commits to squash their commits – it’s just to provide an easy option for folks to clean up a messy commit history (“add new feature; wip; wip; fix; fix; fix; fix; fix;“) without having to use rebase.

I’d be curious to hear about other people who use a workflow like this and if it works well.

there are more problems than I expected

I went into this really feeling like “rebase is fine, what could go wrong?” But many of these problems actually have happened to me in the past, it’s just that over the years I’ve learned how to avoid or fix all of them.

And I’ve never really seen anyone share best practices for rebase, other than “never force push to a shared branch”. All of these honestly make me a lot more reluctant to recommend using rebase.

To recap, I think these are my personal rebase rules I follow:

- stop a rebase if it’s going badly instead of letting it finish (with

git rebase --abort) - know how to use

git reflogto undo a bad rebase - don’t rebase a million tiny commits (instead do it in 2 steps:

git rebase -i HEAD^^^^and thengit rebase main) - don’t do more than one thing in a

git rebase -i. Keep it simple. - never force push to a shared branch

- never rebase commits that have already been pushed to

main

Thanks to Marco Rogers for encouraging me to think about the problems people have with rebase, and to everyone on Mastodon who helped with this.

Confusing git terminology

Hello! I’m slowly working on explaining git. One of my biggest problems is that after almost 15 years of using git, I’ve become very used to git’s idiosyncracies and it’s easy for me to forget what’s confusing about it.

So I asked people on Mastodon:

what git jargon do you find confusing? thinking of writing a blog post that explains some of git’s weirder terminology: “detached HEAD state”, “fast-forward”, “index/staging area/staged”, “ahead of ‘origin/main’ by 1 commit”, etc

I got a lot of GREAT answers and I’ll try to summarize some of them here. Here’s a list of the terms:

- HEAD and “heads”

- “detached HEAD state”

- “ours” and “theirs” while merging or rebasing

- “Your branch is up to date with ‘origin/main’”

- HEAD^, HEAD~ HEAD^^, HEAD~~, HEAD^2, HEAD~2

- .. and …

- “can be fast-forwarded”

- “reference”, “symbolic reference”

- refspecs

- “tree-ish”

- “index”, “staged”, “cached”

- “reset”, “revert”, “restore”

- “untracked files”, “remote-tracking branch”, “track remote branch”

- checkout

- reflog

- merge vs rebase vs cherry-pick

- rebase –onto

- commit

- more confusing terms

I’ve done my best to explain what’s going on with these terms, but they cover basically every single major feature of git which is definitely too much for a single blog post so it’s pretty patchy in some places.

HEAD and “heads”

A few people said they were confused by the terms HEAD and refs/heads/main,

because it sounds like it’s some complicated technical internal thing.

Here’s a quick summary:

- “heads” are “branches”. Internally in git, branches are stored in a directory called

.git/refs/heads. (technically the official git glossary says that the branch is all the commits on it and the head is just the most recent commit, but they’re 2 different ways to think about the same thing) HEADis the current branch. It’s stored in.git/HEAD.

I think that “a head is a branch, HEAD is the current branch” is a good

candidate for the weirdest terminology choice in git, but it’s definitely too

late for a clearer naming scheme so let’s move on.

There are some important exceptions to “HEAD is the current branch”, which we’ll talk about next.

“detached HEAD state”

You’ve probably seen this message:

$ git checkout v0.1

You are in 'detached HEAD' state. You can look around, make experimental

changes and commit them, and you can discard any commits you make in this

state without impacting any branches by switching back to a branch.

[...]

Here’s the deal with this message:

- In Git, usually you have a “current branch” checked out, for example

main. - The place the current branch is stored is called

HEAD. - Any new commits you make will get added to your current branch, and if you run

git merge other_branch, that will also affect your current branch - But

HEADdoesn’t have to be a branch! Instead it can be a commit ID. - Git calls this state (where HEAD is a commit ID instead of a branch) “detached HEAD state”

- For example, you can get into detached HEAD state by checking out a tag, because a tag isn’t a branch

- if you don’t have a current branch, a bunch of things break:

git pulldoesn’t work at all (since the whole point of it is to update your current branch)- neither does

git pushunless you use it in a special way git commit,git merge,git rebase, andgit cherry-pickdo still work, but they’ll leave you with “orphaned” commits that aren’t connected to any branch, so those commits will be hard to find

- You can get out of detached HEAD state by either creating a new branch or switching to an existing branch

“ours” and “theirs” while merging or rebasing

If you have a merge conflict, you can run git checkout --ours file.txt to pick the version of file.txt from the “ours” side. But which side is “ours” and which side is “theirs”?

I always find this confusing and I never use git checkout --ours because of

that, but I looked it up to see which is which.

For merges, here’s how it works: the current branch is “ours” and the branch you’re merging in is “theirs”, like this. Seems reasonable.

$ git checkout merge-into-ours # current branch is "ours"

$ git merge from-theirs # branch we're merging in is "theirs"

For rebases it’s the opposite – the current branch is “theirs” and the target branch we’re rebasing onto is “ours”, like this:

$ git checkout theirs # current branch is "theirs"

$ git rebase ours # branch we're rebasing onto is "ours"

I think the reason for this is that under the hood git rebase main is

repeatedly merging commits from the current branch into a copy of the main branch (you can

see what I mean by that in this weird shell script the implements git rebase using git merge. But I

still find it confusing.

This nice tiny site explains the “ours” and “theirs” terms.

A couple of people also mentioned that VSCode calls “ours”/“theirs” “current change”/“incoming change”, and that it’s confusing in the exact same way.

“Your branch is up to date with ‘origin/main’”

This message seems straightforward – it’s saying that your main branch is up

to date with the origin!

But it’s actually a little misleading. You might think that this means that

your main branch is up to date. It doesn’t. What it actually means is –

if you last ran git fetch or git pull 5 days ago, then your main branch

is up to date with all the changes as of 5 days ago.

So if you don’t realize that, it can give you a false sense of security.

I think git could theoretically give you a more useful message like “is up to

date with the origin’s main as of your last fetch 5 days ago” because the time

that the most recent fetch happened is stored in the reflog, but it doesn’t.

HEAD^, HEAD~ HEAD^^, HEAD~~, HEAD^2, HEAD~2

I’ve known for a long time that HEAD^ refers to the previous commit, but I’ve

been confused for a long time about the difference between HEAD~ and HEAD^.

I looked it up, and here’s how these relate to each other:

HEAD^andHEAD~are the same thing (1 commit ago)HEAD^^^andHEAD~~~andHEAD~3are the same thing (3 commits ago)HEAD^3refers the the third parent of a commit, and is different fromHEAD~3

This seems weird – why are HEAD~ and HEAD^ the same thing? And what’s the

“third parent”? Is that the same thing as the parent’s parent’s parent? (spoiler: it

isn’t) Let’s talk about it!

Most commits have only one parent. But merge commits have multiple parents –

they’re merging together 2 or more commits. In Git HEAD^ means “the parent of

the HEAD commit”. But what if HEAD is a merge commit? What does HEAD^ refer

to?

The answer is that HEAD^ refers to the the first parent of the merge,

HEAD^2 is the second parent, HEAD^3 is the third parent, etc.

But I guess they also wanted a way to refer to “3 commits ago”, so HEAD^3 is

the third parent of the current commit (which may have many parents if it’s a merge commit), and HEAD~3 is the parent’s parent’s

parent.

I think in the context of the merge commit ours/theirs discussion earlier, HEAD^ is “ours” and HEAD^2 is “theirs”.

.. and ...

Here are two commands:

git log main..testgit log main...test

What’s the difference between .. and ...? I never use these so I had to look it up in man git-range-diff. It seems like the answer is that in this case:

A - B main

\

C - D test

main..testis commits C and Dtest..mainis commit Bmain...testis commits B, C, and D

But it gets worse: apparently git diff also supports .. and ..., but

they do something completely different than they do with git log? I think the summary is:

git log test..mainshows changes onmainthat aren’t ontest, whereasgit log test...mainshows changes on both sides.git diff test..mainshowstestchanges andmainchanges (it diffsBandD) whereasgit diff test...maindiffsAandD(it only shows you the diff on one side).

this blog post talks about it a bit more.

“can be fast-forwarded”

Here’s a very common message you’ll see in git status:

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is behind 'origin/main' by 2 commits, and can be fast-forwarded.

(use "git pull" to update your local branch)

What does “fast-forwarded” mean? Basically it’s trying to say that the two branches look something like this: (newest commits are on the right)

main: A - B - C

origin/main: A - B - C - D - E

or visualized another way:

A - B - C - D - E (origin/main)

|

main

Here origin/main just has 2 extra commits that main doesn’t have, so it’s

easy to bring main up to date – we just need to add those 2 commits.

Literally nothing can possibly go wrong – there’s no possibility of merge

conflicts. A fast forward merge is a very good thing! It’s the easiest way to combine 2 branches.

After running git pull, you’ll end up this state:

main: A - B - C - D - E

origin/main: A - B - C - D - E

Here’s an example of a state which can’t be fast-forwarded.

A - B - C - X (main)

|

- - D - E (origin/main)

Here main has a commit that origin/main doesn’t have (X). So

you can’t do a fast forward. In that case, git status would say:

$ git status

Your branch and 'origin/main' have diverged,

and have 1 and 2 different commits each, respectively.

“reference”, “symbolic reference”

I’ve always found the term “reference” kind of confusing. There are at least 3 things that get called “references” in git

- branches and tags like

mainandv0.2 HEAD, which is the current branch- things like

HEAD^^^which git will resolve to a commit ID. Technically these are probably not “references”, I guess git calls them “revision parameters” but I’ve never used that term.

“symbolic reference” is a very weird term to me because personally I think the only

symbolic reference I’ve ever used is HEAD (the current branch), and HEAD

has a very central place in git (most of git’s core commands’ behaviour depends

on the value of HEAD), so I’m not sure what the point of having it as a

generic concept is.

refspecs

When you configure a git remote in .git/config, there’s this +refs/heads/main:refs/remotes/origin/main thing.

[remote "origin"]

url = git@github.com:jvns/pandas-cookbook

fetch = +refs/heads/main:refs/remotes/origin/main

I don’t really know what this means, I’ve always just used whatever the default

is when you do a git clone or git remote add, and I’ve never felt any

motivation to learn about it or change it from the default.

“tree-ish”

The man page for git checkout says:

git checkout [-f|--ours|--theirs|-m|--conflict=<style>] [<tree-ish>] [--] <pathspec>...

What’s tree-ish??? What git is trying to say here is when you run git checkout THING ., THING can be either:

- a commit ID (like

182cd3f) - a reference to a commit ID (like

mainorHEAD^^orv0.3.2) - a subdirectory inside a commit (like

main:./docs) - I think that’s it????

Personally I’ve never used the “directory inside a commit” thing and from my perspective “tree-ish” might as well just mean “commit or reference to commit”.

“index”, “staged”, “cached”

All of these refer to the exact same thing (the file .git/index, which is where your changes are staged when you run git add):

git diff --cachedgit rm --cachedgit diff --staged- the file

.git/index

Even though they all ultimately refer to the same file, there’s some variation in how those terms are used in practice:

- Apparently the flags

--indexand--cacheddo not generally mean the same thing. I have personally never used the--indexflag so I’m not going to get into it, but this blog post by Junio Hamano (git’s lead maintainer) explains all the gnarly details - the “index” lists untracked files (I guess for performance reasons) but you don’t usually think of the “staging area” as including untracked files”

“reset”, “revert”, “restore”

A bunch of people mentioned that “reset”, “revert” and “restore” are very similar words and it’s hard to differentiate them.

I think it’s made worse because

git reset --hardandgit restore .on their own do basically the same thing. (thoughgit reset --hard COMMITandgit restore --source COMMIT .are completely different from each other)- the respective man pages don’t give very helpful descriptions:

git reset: “Reset current HEAD to the specified state”git revert: “Revert some existing commits”git restore: “Restore working tree files”

Those short descriptions do give you a better sense for which noun is being affected (“current HEAD”, “some commits”, “working tree files”) but they assume you know what “reset”, “revert” and “restore” mean in this context.

Here are some short descriptions of what they each do:

git revert COMMIT: Create a new commit that’s the “opposite” of COMMIT on your current branch (if COMMIT added 3 lines, the new commit will delete those 3 lines)git reset --hard COMMIT: Force your current branch back to the state it was atCOMMIT, erasing any new changes sinceCOMMIT. Very dangerous operation.git restore --source=COMMIT PATH: Take all the files inPATHback to how they were atCOMMIT, without changing any other files or commit history.

“untracked files”, “remote-tracking branch”, “track remote branch”

Git uses the word “track” in 3 different related ways:

Untracked files:in the output ofgit status. This means those files aren’t managed by Git and won’t be included in commits.- a “remote tracking branch” like

origin/main. This is a local reference, and it’s the commit ID thatmainpointed to on the remoteoriginthe last time you rangit pullorgit fetch. - “branch foo set up to track remote branch bar from origin”

The “untracked files” and “remote tracking branch” thing is not too bad – they both use “track”, but the context is very different. No big deal. But I think the other two uses of “track” are actually quite confusing:

mainis a branch that tracks a remoteorigin/mainis a remote-tracking branch

But a “branch that tracks a remote” and a “remote-tracking branch” are different things in Git and the distinction is pretty important! Here’s a quick summary of the differences:

mainis a branch. You can make commits to it, merge into it, etc. It’s often configured to “track” the remotemainin.git/config, which means that you can usegit pullandgit pushto push/pull changes.origin/mainis not a branch. It’s a “remote-tracking branch”, which is not a kind of branch (I’m sorry). You can’t make commits to it. The only way you can update it is by runninggit pullorgit fetchto get the latest state ofmainfrom the remote.

I’d never really thought about this ambiguity before but I think it’s pretty easy to see why folks are confused by it.

checkout

Checkout does two totally unrelated things:

git checkout BRANCHswitches branchesgit checkout file.txtdiscards your unstaged changes tofile.txt

This is well known to be confusing and git has actually split those two

functions into git switch and git restore (though you can still use

checkout if, like me, you have 15 years of muscle memory around git checkout

that you don’t feel like unlearning)

Also personally after 15 years I still can’t remember the order of the

arguments to git checkout main file.txt for restoring the version of

file.txt from the main branch.

I think sometimes you need to pass -- to checkout as an argument somewhere

to help it figure out which argument is a branch and which ones are paths but I

never do that and I’m not sure when it’s needed.

reflog

Lots of people mentioning reading reflog as re-flog and not ref-log. I

won’t get deep into the reflog here because this post is REALLY long but:

- “reference” is an umbrella term git uses for branches, tags, and HEAD

- the reference log (“reflog”) gives you the history of everything a reference has ever pointed to

- It can help get you out of some VERY bad git situations, like if you accidentally delete an important branch

- I find it one of the most confusing parts of git’s UI and I try to avoid needing to use it.

merge vs rebase vs cherry-pick

A bunch of people mentioned being confused about the difference between merge and rebase and not understanding what the “base” in rebase was supposed to be.

I’ll try to summarize them very briefly here, but I don’t think these 1-line explanations are that useful because people structure their workflows around merge / rebase in pretty different ways and to really understand merge/rebase you need to understand the workflows. Also pictures really help. That could really be its whole own blog post though so I’m not going to get into it.

- merge creates a single new commit that merges the 2 branches

- rebase copies commits on the current branch to the target branch, one at a time.

- cherry-pick is similar to rebase, but with a totally different syntax (one big difference is that rebase copies commits FROM the current branch, cherry-pick copies commits TO the current branch)

rebase --onto

git rebase has an flag called onto. This has always seemed confusing to me

because the whole point of git rebase main is to rebase the current branch

onto main. So what’s the extra onto argument about?

I looked it up, and --onto definitely solves a problem that I’ve rarely/never

actually had, but I guess I’ll write down my understanding of it anyway.

A - B - C (main)

\

D - E - F - G (mybranch)

|

otherbranch

Imagine that for some reason I just want to move commits F and G to be

rebased on top of main. I think there’s probably some git workflow where this

comes up a lot.

Apparently you can run git rebase --onto main otherbranch mybranch to do

that. It seems impossible to me to remember the syntax for this (there are 3

different branch names involved, which for me is too many), but I heard about it from a

bunch of people so I guess it must be useful.

commit

Someone mentioned that they found it confusing that commit is used both as a verb and a noun in git.

for example:

- verb: “Remember to commit often”

- noun: “the most recent commit on

main“

My guess is that most folks get used to this relatively quickly, but this use of “commit” is different from how it’s used in SQL databases, where I think “commit” is just a verb (you “COMMIT” to end a transaction) and not a noun.

Also in git you can think of a Git commit in 3 different ways:

- a snapshot of the current state of every file

- a diff from the parent commit

- a history of every previous commit

None of those are wrong: different commands use commits in all of these ways.

For example git show treats a commit as a diff, git log treats it as a

history, and git restore treats it as a snapshot.

But git’s terminology doesn’t do much to help you understand in which sense a commit is being used by a given command.

more confusing terms

Here are a bunch more confusing terms. I don’t know what a lot of these mean.

things I don’t really understand myself:

- “the git pickaxe” (maybe this is

git log -Sandgit log -G, for searching the diffs of previous commits?) - submodules (all I know is that they don’t work the way I want them to work)

- “cone mode” in git sparse checkout (no idea what this is but someone mentioned it)

things that people mentioned finding confusing but that I left out of this post because it was already 3000 words:

- blob, tree

- the direction of “merge”

- “origin”, “upstream”, “downstream”

- that

pushandpullaren’t opposites - the relationship between

fetchandpull(pull = fetch + merge) - git porcelain

- subtrees

- worktrees

- the stash

- “master” or “main” (it sounds like it has a special meaning inside git but it doesn’t)

- when you need to use

origin main(likegit push origin main) vsorigin/main

github terms people mentioned being confused by:

- “pull request” (vs “merge request” in gitlab which folks seemed to think was clearer)

- what “squash and merge” and “rebase and merge” do (I’d never actually heard of

git merge --squashuntil yesterday, I thought “squash and merge” was a special github feature)

it’s genuinely “every git term”

I was surprised that basically every other core feature of git was mentioned by at least one person as being confusing in some way. I’d be interested in hearing more examples of confusing git terms that I missed too.

There’s another great post about this from 2012 called the most confusing git terminology. It talks more about how git’s terminology relates to CVS and Subversion’s terminology.

If I had to pick the 3 most confusing git terms, I think right now I’d pick:

- a

headis a branch,HEADis the current branch - “remote tracking branch” and “branch that tracks a remote” being different things

- how “index”, “staged”, “cached” all refer to the same thing

that’s all!

I learned a lot from writing this – I learned a few new facts about git, but more importantly I feel like I have a slightly better sense now for what someone might mean when they say that everything in git is confusing.

I really hadn’t thought about a lot of these issues before – like I’d never realized how “tracking” is used in such a weird way when discussing branches.

Also as usual I might have made some mistakes, especially since I ended up in a bunch of corners of git that I hadn’t visited before.

Also a very quick plug: I’m working on writing a zine about git, if you’re interested in getting an email when it comes out you can sign up to my very infrequent announcements mailing list.

translations of this post

Some miscellaneous git facts

I’ve been very slowly working on writing about how Git works. I thought I already knew Git pretty well, but as usual when I try to explain something I’ve been learning some new things.

None of these things feel super surprising in retrospect, but I hadn’t thought about them clearly before.

The facts are:

- the “index”, “staging area” and “–cached” are all the same thing

- the stash is a bunch of commits

- not all references are branches or tags

- merge commits aren’t empty

Let’s talk about them!

the “index”, “staging area” and “–cached” are all the same thing

When you run git add file.txt, and then git status, you’ll see something like this:

$ git add content/post/2023-10-20-some-miscellaneous-git-facts.markdown

$ git status

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

new file: content/post/2023-10-20-some-miscellaneous-git-facts.markdown

People usually call this “staging a file” or “adding a file to the staging area”.

When you stage a file with git add, behind the scenes git adds the file to its object

database (in .git/objects) and updates a file called .git/index to refer to

the newly added file.

This “staging area” actually gets referred to by 3 different names in Git. All

of these refer to the exact same thing (the file .git/index):

git diff --cachedgit diff --staged- the file

.git/index

I felt like I should have realized this earlier, but I didn’t, so there it is.

the stash is a bunch of commits

When I run git stash to stash my changes, I’ve always been a bit confused

about where those changes actually went. It turns out that when you run git

stash, git makes some commits with your changes and labels them with a reference

called stash (in .git/refs/stash).

Let’s stash this blog post and look at the log of the stash reference:

$ git log stash --oneline

6cb983fe (refs/stash) WIP on main: c6ee55ed wip

2ff2c273 index on main: c6ee55ed wip

... some more stuff

Now we can look at the commit 2ff2c273 to see what it contains:

$ git show 2ff2c273 --stat

commit 2ff2c273357c94a0087104f776a8dd28ee467769

Author: Julia Evans <julia@jvns.ca>

Date: Fri Oct 20 14:49:20 2023 -0400

index on main: c6ee55ed wip

content/post/2023-10-20-some-miscellaneous-git-facts.markdown | 40 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Unsurprisingly, it contains this blog post. Makes sense!

git stash actually creates 2 separate commits: one for the index, and one for

your changes that you haven’t staged yet. I found this kind of heartening

because I’ve been working on a tool to snapshot and restore the state of a git

repository (that I may or may not ever release) and I came up with a very

similar design, so that made me feel better about my choices.

Apparently older commits in the stash are stored in the reflog.

not all references are branches or tags

Git’s documentation often refers to “references” in a generic way that I find

a little confusing sometimes. Personally 99% of the time when I deal with

a “reference” in Git it’s a branch or HEAD and the other 1% of the time it’s a tag. I

actually didn’t know ANY examples of references that weren’t branches or tags or HEAD.

But now I know one example – the stash is a reference, and it’s not a branch or tag! So that’s cool.

Here are all the references in my blog’s git repository (other than HEAD):

$ find .git/refs -type f

.git/refs/heads/main

.git/refs/remotes/origin/HEAD

.git/refs/remotes/origin/main

.git/refs/stash

Some other references people mentioned in reponses to this post:

refs/notes/*, fromgit notesrefs/pull/123/head, and `refs/pull/123/headfor GitHub pull requests (which you can get withgit fetch origin refs/pull/123/merge)refs/bisect/*, fromgit bisect

merge commits aren’t empty

Here’s a toy git repo where I created two branches x and y, each with 1

file (x.txt and y.txt) and merged them. Let’s look at the merge commit.

$ git log --oneline

96a8afb (HEAD -> y) Merge branch 'x' into y

0931e45 y

1d8bd2d (x) x

If I run git show 96a8afb, the commit looks “empty”: there’s no diff!

git show 96a8afb

commit 96a8afbf776c2cebccf8ec0dba7c6c765ea5d987 (HEAD -> y)

Merge: 0931e45 1d8bd2d

Author: Julia Evans <julia@jvns.ca>

Date: Fri Oct 20 14:07:00 2023 -0400

Merge branch 'x' into y

But if I diff the merge commit against each of its two parent commits separately, you can see that of course there is a diff:

$ git diff 0931e45 96a8afb --stat

x.txt | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

$ git diff 1d8bd2d 96a8afb --stat

y.txt | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

It seems kind of obvious in retrospect that merge commits aren’t actually “empty” (they’re snapshots of the current state of the repo, just like any other commit), but I’d never thought about why they appear to be empty.

Apparently the reason that these merge diffs are empty is that merge diffs only show conflicts – if I instead create a repo

with a merge conflict (one branch added x and another branch added y to the

same file), and show the merge commit where I resolved the conflict, it looks

like this:

$ git show HEAD

commit 3bfe8311afa4da867426c0bf6343420217486594

Merge: 782b3d5 ac7046d

Author: Julia Evans <julia@jvns.ca>

Date: Fri Oct 20 15:29:06 2023 -0400

Merge branch 'x' into y

diff --cc file.txt

index 975fbec,587be6b..b680253

--- a/file.txt

+++ b/file.txt

@@@ -1,1 -1,1 +1,1 @@@

- y

-x

++z

It looks like this is trying to tell me that one branch added x, another

branch added y, and the merge commit resolved it by putting z instead. But

in the earlier example, there was no conflict, so Git didn’t display a diff at all.

(thanks to Jordi for telling me how merge diffs work)

that’s all!

I’ll keep this post short, maybe I’ll write another blog post with more git facts as I learn them.

New talk: Making Hard Things Easy

A few weeks ago I gave a keynote at Strange Loop called Making Hard Things Easy. It’s about why I think some things are hard to learn and ideas for how we can make them easier.

Here’s the video, as well as the slides and a transcript of (roughly) what I said in the talk.

the video

the transcript

I often give talks about things that I'm excited about, or that I think are really fun.

But today, I want to talk about something that I'm a little bit mad about, which is that sometimes things that seem like they should be basic take me 10 years or 20 years to learn, way longer than it seems like they should.

And sometimes this would feel kind of personal! This shouldn't be so hard for me! I should understand this already. It's been seven years!

And this "it's just me" attitude is often encouraged -- when I write about finding things hard to learn on the Internet, Internet strangers will sometimes tell me: "yeah, this is easy! You should get it already! Maybe you're just not very smart!"

But luckily I have a pretty big ego so I don't take the internet strangers too seriously. And I have a lot of patience so I'm willing to keep coming back to a topic I'm confused about. There were maybe four different things that were going wrong with DNS in my life and eventually I figured them all out.

So, hooray! I understood DNS! I win! But then I see some of my friends struggling with the exact same things.

They're wondering, hey, my DNS isn't working. Why not?

And it doesn't end. We're still having the same problems over and over and over again. And it's frustrating! It feels redundant! It makes me mad. Especially when friends take it personally, and they feel like "hey I should really understand this already".

Because everyone is going through this. From the sounds of recognition I hear, I think a lot of you have been through some of these same problems with DNS.

I started a little publishing company called Wizard Zines where --

(applause)

Wow. Where I write about some of these topics and try to demystify them.

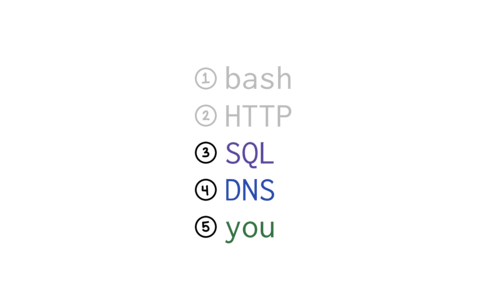

We're going to talk about bash, HTTP, SQL, and DNS.

For each of them, we're going to talk a little bit about:

a. what's so hard about it?

b. what are some things we can do to make it a little bit easier for each other?

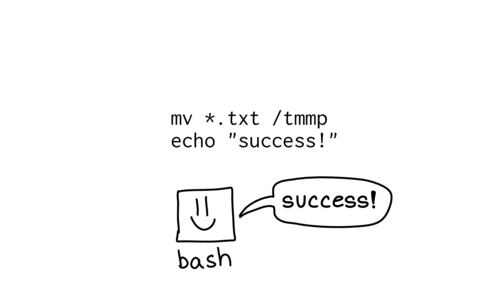

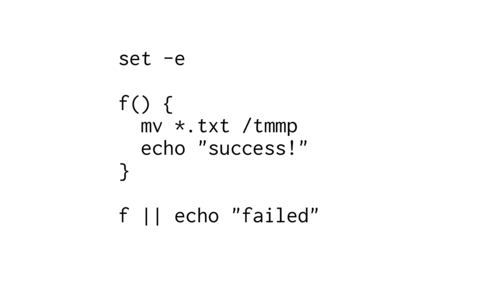

First, let's run this script, bad.sh:

mv ./*.txt /tmmpp echo "success!"

This moves a file and prints "success!". And with most of the programming languages that I use, if there's a problem, the program will stop.

[laughter from audience]

But I think a lot of you know from maybe sad experience that bash does not stop, right? It keeps going. And going... and sometimes very bad things happen to your computer in the process.

When I run this program, here's the output:

mv: cannot stat './*.txt': No such file or directory success!

It didn't stop after the failed mv.

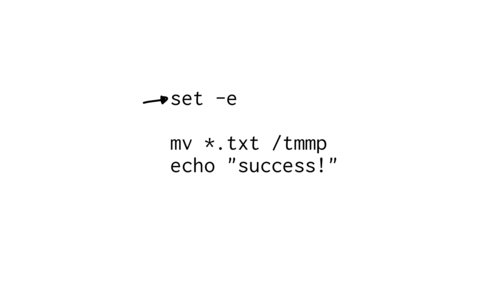

Eventually I learned that you can write set

-e at the top of your program, and that will make bash stop if

there's a problem.

When we run this new program with set -e at the top, here's the output:

mv: cannot stat './*.txt': No such file or directory

Here we've put our code in a function. And if the function fails, we want to echo "failed".

So use set -e at the beginning, and you might think everything should be okay.

But if we run it... this is the output we get

mv: cannot stat './*.txt': No such file or directory success

We get the "success" message again! It didn't stop, it just kept going. This is

because the "or" (|| echo "failed") globally disables set -e in the

function.

Which is certainly not what I wanted, and not what I would expect. But this is not a bug in bash, it's is the documented behavior.

And I think one reason this is tricky is a lot of us don't use bash very often. Maybe you write a bash script every six months and don't look at it again.

When you use a system very infrequently and it's full of a lot of weird trivia and gotchas, it's hard to use the system correctly.

But I would say this is factually untrue. How many of you are using bash?

A lot of us ARE using it! And it doesn't always work perfectly, but often it gets the job done.

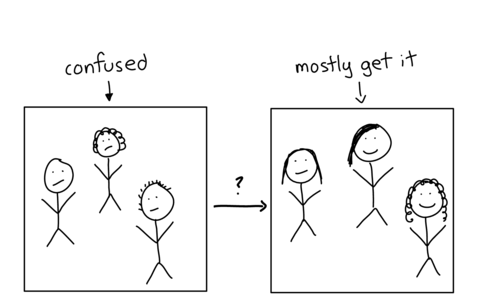

The way I think this is -- you have some people on the left in this diagram who are confused about bash, who think it seems awful and incomprehensible.

And some people on the right who know how to make the bash work for them, mostly.

So how do we move people from the left to the right, from being overwhelmed by a pile of impossible gotchas to being able to mostly use the system correctly?

And for bash, we have this incredible tool called shellcheck.

[ Applause ]

Yes! Shellcheck is amazing! And shellcheck knows a lot of things that can go wrong and can tell you "oh no, you don't want to do that. You're going to have a bad time."

I'm very grateful for shellcheck, it makes it much easier for me to write tiny bash scripts from time to time.

Now let's do a shellcheck demo!

$ shellcheck -o all bad-again.sh In bad-again.sh line 7: f || echo "failed!" ^-- SC2310 (info): This function is invoked in an || condition so set -e will be disabled. Invoke separately if failures should cause the script to exit.

Shellcheck gives us this

lovely error message. The message isn't completely obvious on its own (and this

check is only run if you invoke shellcheck with -o all). But

shellcheck tells you "hey, there's this problem, maybe you should be worried

about that".

And I think it's wonderful that all these tips live in this linter.

I'm not trying to tell you to write linters, though I think that some of you probably will write linters because this is that kind of crowd.

I've personally never written a linter, and I'm definitely not going to create something as cool as shellcheck!

But instead, the way I write linters is I tell people about shellcheck from time to time and then I feel a little like I invented shellcheck for those people. Because some people didn't know about the tool until I told them about it!

I didn't find out about shellcheck for a long time and I was kind of mad about it when I found out. I felt like -- excuse me? I could have been using shellcheck this whole time? I didn't need to remember all of this stuff in my brain?

So I think an incredible thing we can do is to reflect on the tools that we're using to reduce our cognitive load and all the things that we can't fit into our minds, and make sure our friends or coworkers know about them.

I also like to warn people about gotchas and some of the terrible things computers have done to me.

I think this is an incredibly valuable community service. The example I shared

about how set -e got disabled is something I learned from my

friend Jesse a few weeks ago.

They told me how this thing happened to them, and now I know and I don't have to go through it personally.

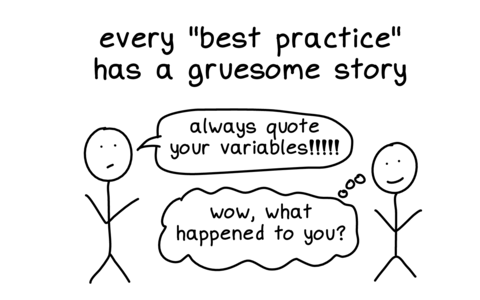

One way I see people kind of trying to share terrible things that their computers have done to them is by sharing "best practices".

But I really love to hear the stories behind the best practices!

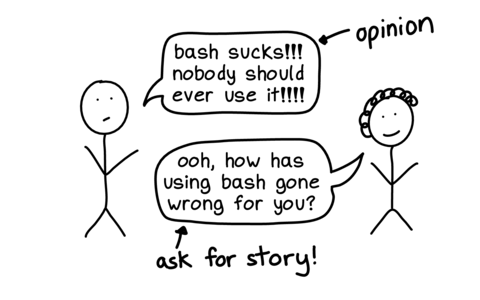

If someone has a strong opinion like "nobody should ever use bash", I want to hear about the story! What did bash do to you? I need to know.

The reason I prefer stories to best practices is if I know the story about how the bash hurt you, I can take that information and decide for myself how I want to proceed.

Maybe I feel like -- the computer did that to you? That's okay, I can deal with that problem, I don't mind.

Or I might instead feel like "oh no, I'm going to do the best practice you recommended, because I do not want that thing to happen to me".

These bash stories are a great example of that: my reaction to them is "okay, I'm going to keep using bash, I'll just use shellcheck and keep my bash scripts pretty simple". But other people see them and decide "wow, I never want to use bash for anything, that's awful, I hate it".

Different people have different reactions to the same stories and that's okay.

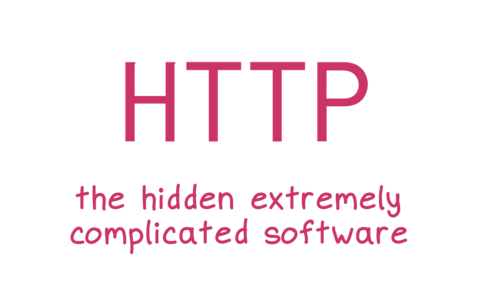

I was talking to Marco Rogers at some point, many years ago, and he mentioned some new developers he was working with were struggling with HTTP.

And at first, I was a little confused about this -- I didn't understand what was hard about HTTP.

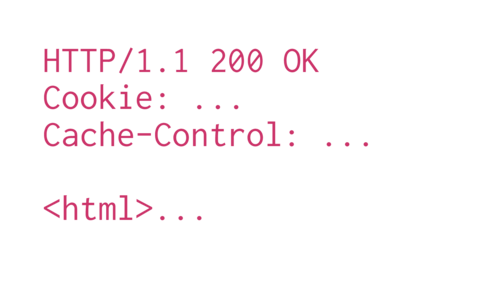

The way I was thinking about it at the time was that if you have an HTTP response, it has a few parts: a response code, some headers, and a body.

I felt like -- that's a pretty simple structure, what's the problem? But of course there was a problem, I just couldn't see what it was at first.

So, I talked to a friend who was newer to HTTP. And they asked "why does it matter what headers you set?"

And I said: "well, the browser..."

The browser!

Firefox is 20 million lines of code! It's been evolving since the '90s. There have been as I understand it, 1 million changes to the browser security model as people have discovered new and exciting exploits and the web has become a scarier and scarier place.

The browser is really a lot to understand.

One trick for understanding why a topic is hard is -- if the implementation if the thing involves 20 million lines of code, maybe that's why people are confused!

Though that 20 million lines of code also involves CSS and JS and many other things that aren't HTTP, but still.

Once I thought of it in terms of how complex a modern web browser is, it made so much more sense! Of course newcomers are confused about HTTP if you have to understand what the browser is doing!

Then my problem changed from "why is this hard?" to "how do I explain this at all?"

So how do we make it easier? How do we wrap our minds around this 20 million lines of code?

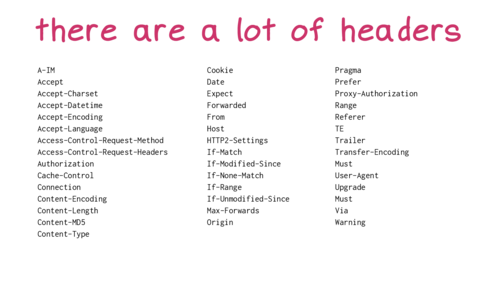

One way I think about this for HTTP is: here are some of the HTTP request headers. That's kind of a big list there are 43 headers there.

There are more unofficial headers too.

My brain does not contain all of those headers, I have no idea what most of them are.

When I think about trying to explain big topics, I think about -- what is actually in my brain, which only contains a normal human number of things?

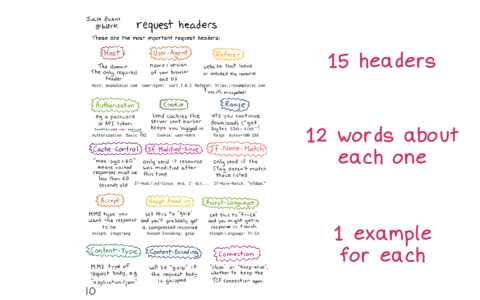

This is a comic I drew about HTTP request headers. You don't have to read the whole thing. This has 15 request headers.

I wrote that these are "the most important headers", but what I mean by "most important" here is that these are the ones that I know about and use. It's a subjective list.

I wrote about 12 words about each one, which I think is approximately the amount of information about each header that lives in my mind.

For example I know that you can set Accept-Encoding to gzip

and then you might get back a compressed response. That's all I know,

and that's usually all I need to know!

This very small set of information is working pretty well for me.

The general way I think about this trick is "turn a big list into a small list".

Turn the set of EVERY SINGLE THING into just the things I've personally used. I find it helps a lot.

Another example of this "turn a big list into a small list" trick is command line arguments.

I use a lot of command line tools, the number of arguments they have can be overwhelming, and I've written about them a fair amount over the years.

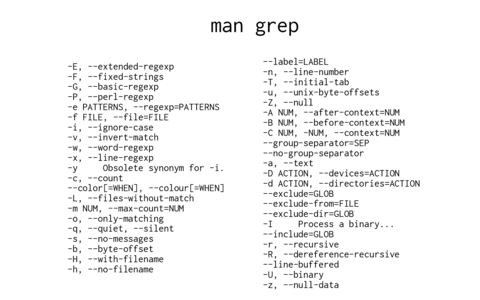

Here are all the flags for grep, from its man page. That's too much! I've been using grep for 20 years but I don't know what all that stuff is.

But when I look at the grep man page, this is what I see.

I think it's very helpful to newcomers when a more experienced person says "look, I've been using this system for a while, I know about 7 things about it, and here's what they are".

We're just pruning those lists down to a more human scale. And it can even help other more experienced people -- often someone else will know a slightly different set of 7 things from me.

But what about the stuff that doesn't fit in my brain?

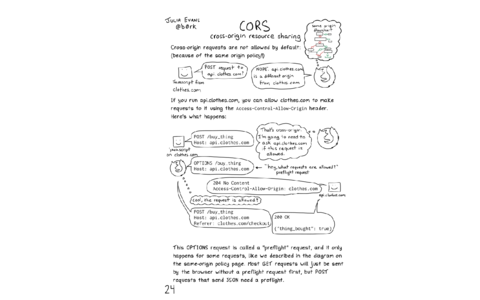

Because I have a few things about HTTP stored in my brain. But sometimes I need other information which is hard to remember, like maybe the exact details of how CORS works.

I often have trouble finding the right references.

For example I've been trying to learn CSS off and on for 20 years. I've made a lot of progress -- it's going well!

But only in the last 2 years or so I learned about this wonderful website called CSS Tricks.

And I felt kind of mad when I learned about CSS Tricks! Why didn't I know about this before? It would have helped me!

But anyway, I'm happy to know about CSS Tricks now. (though sadly they seem to have stopped publishing in April after the acquisition, I'm still happy the older posts are there)

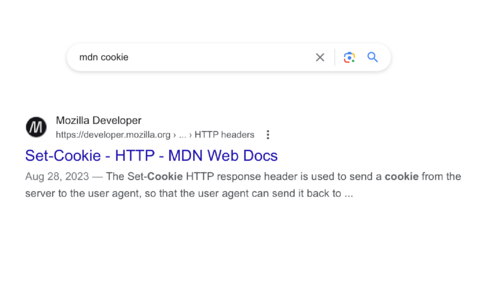

For HTTP, I think a lot of us use the Mozilla Developer Network.

Another HTTP reference I love is the official RFC, RFC 9110 (also 9111, 9112, 9113, 9114)

It's a new authoritative reference for HTTP and it was written just last

year, in 2022! They decided to organize all the information really nicely. So if you

want to know exactly what the Connection header does, you can look

it up.

This is not really my top reference. I'm usually on MDN. But I really appreciate that it's available.

So I love to share my favorite references.

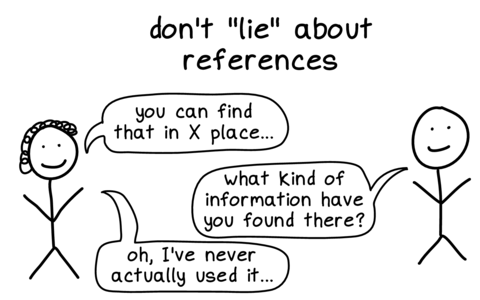

I do sometimes find it tempting to kind of lie about references. Not on purpose. But I'll see something on the internet, and I'll think it's kind of cool, and tell a friend about. But then my friend might ask me -- "when have you used this?" And I'll have to admit "oh, never, I just thought it seemed cool".

I think it's important to be honest about what the references that I'm actually using in real life are. Even if maybe the real references I use are a little "embarrassing", like maybe w3schools or something.

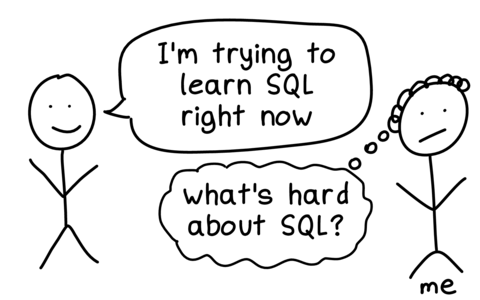

I started thinking about SQL because someone mentioned they're trying to learn SQL. I get most of my zine ideas that way, one person will make an offhand comment and I'll decide "ok, I'm going to spend 4 months writing about that". It's a weird process.

So I was wondering -- what's hard about SQL? What gets in the way of trying to learn that?

I want to say that when I'm confused about what's hard about something, that's a fact about me. It's not usually that the thing is easy, it's that I need to work on understanding what's hard about it. It's easy to forget when you've been using something for a while.

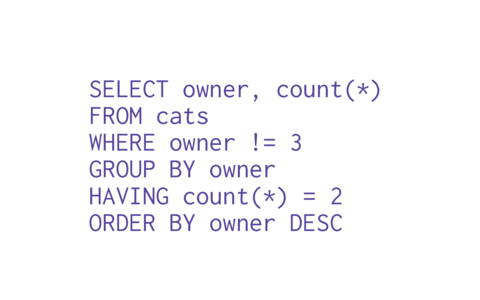

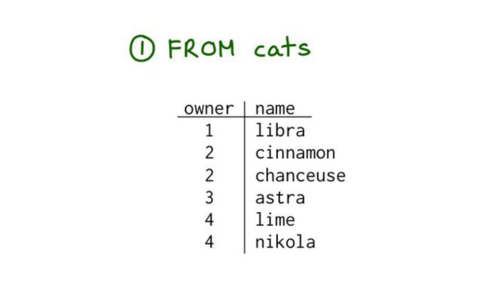

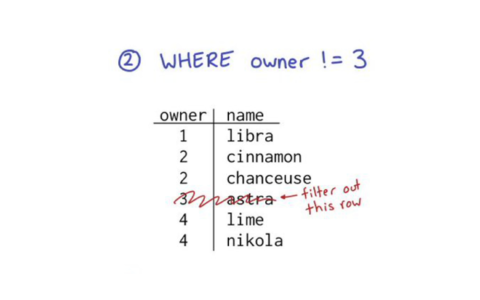

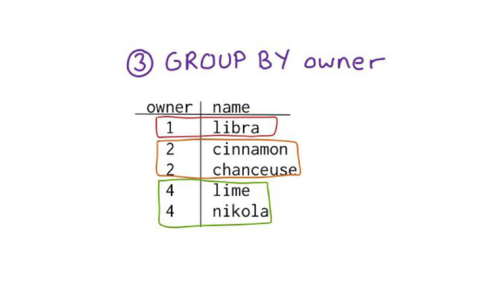

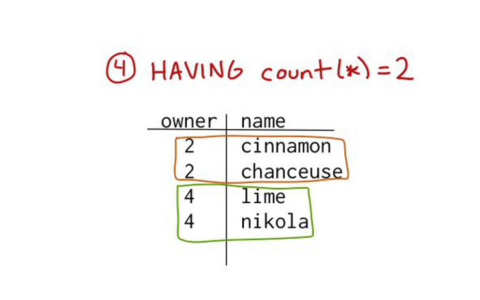

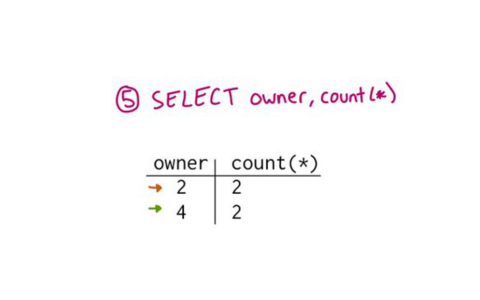

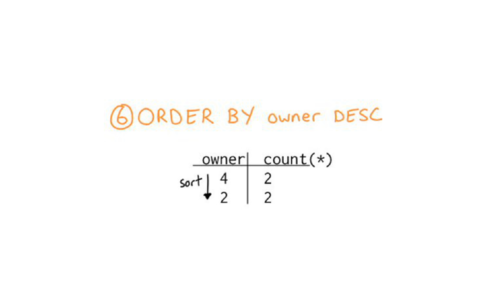

So, I was used to reading SQL queries. For example this made up query that tries to find people who own exactly two cats. It felt straightforward to me, SELECT, FROM, WHERE, GROUP BY.

But then I was talking to a friend about these queries who was new to SQL. And my friend asked -- what is this doing?

I thought, hmm, fair point.

And I think the point my friend was making was that the order that this SQL query is written in, is not the order that it actually happens in. It happens in a different order, and it's not immediately obvious what that is.

I like to think about: what does the computer do first? What actually happens first chronologically?

Computers actually do live in the same timeline as us. Things happen. Things happen in an order. So what happens first?

cats.

So, that's how I think about SQL. The way a query runs is first FROM, then WHERE, GROUP BY, HAVING, SELECT, ORDER BY, LIMIT.

At least conceptually. Real life databases have optimizations and it's more complicated than that. But this is the mental model that I use most of the time and it works for me. Everything is in the same order as you write it, except SELECT is fifth.

One is CORS, in HTTP.

This comic is way too small to read on the slide. But the idea is if you're making a cross-origin request in your browser, you can write down every communication that's happening between your browser and the server, in chronological order.

And I think writing down everything in chronological order makes it a lot easier to understand and more concrete.

"What happens in chronological order?" is a very straightforward structure, which is what I like about it. "What happens first?" feels like it should be easy to answer. But it's not!

I've found that it's actually very hard to know what our computers is doing, and it's a really fun question to explore.

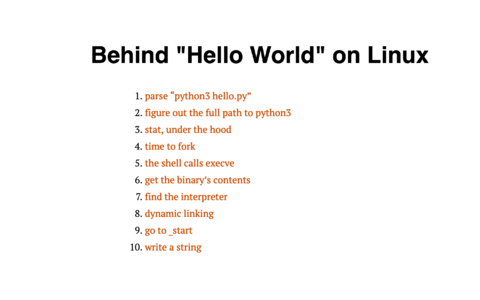

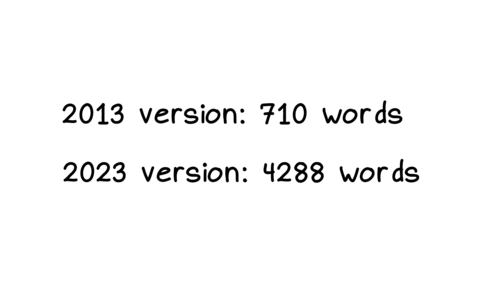

As an example of how this is hard: I wrote a blog post recently called "Behind Hello World on Linux". It's about what happens when you run "hello world" on a Linux computer. I wrote a bunch about it, and I was really happy with it.

But after I wrote the post, I thought -- haven't I written about this before? Maybe 10 years ago?

And sure enough, I'd tried to write a similar post 10 years before.

I think this is really cool. Because the 2013 version of this post was about 6 times shorter. This isn't because Linux is more complicated than it was 10 years ago -- I think everything in the 2023 post was probably also true in 2013. The 2013 post just has a lot less information in it.

The reason the 2023 post is longer is that I didn't know what was happening chronologically on my computer in 2013 very well, and in 2023 I know a lot more. Maybe in 2033 I'll know even more!

I think a lot of us -- like me in 2013 and honestly me now, often don't know the facts of what's happening on our computers. It's very hard, which is what makes it such a fun question to try and discuss.

I think it's cool that all of us have different knowledge about what is happening chronologically on our computers and we can all chip in to this conversation.

For example when I posted this blog post about Hello World on Linux, some people mentioned that they had a lot of thoughts about what happens exactly in your terminal, or more details about the filesystem, or about what's happening internally in the Python interpreter, or any number of things. You can go really deep.

I think it's just a really fun collaborative question.

I've seen "what happens chronologically?" work really well as an activity with coworkers, where you're ask: "when a request comes into this API endpoint we run, how does that work? What happens?"

What I've seen is that someone will understand some part of the system, like "X happens, then Y happens, then it goes over to the database and I have no idea how that works". And then someone else can chime in and say "ah, yes, with the database A B C happens, but then there's a queue and I don't know about that".

I think it's really fun to get together with people who have different specializations and try to make these little timelines of what the computers are doing. I've learned a lot from doing that with people.

Even though I struggled with DNS. Once I got figured it out, I felt like "dude, this is easy!". Even though it just took me 10 years to learn how it works.

But of course, DNS was pretty hard for me to learn. So -- why is that? Why did it take me so long?

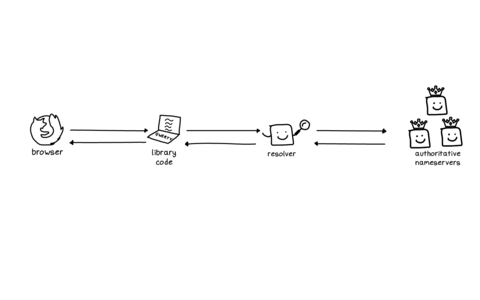

So, I have a little chart here of how I think about DNS.

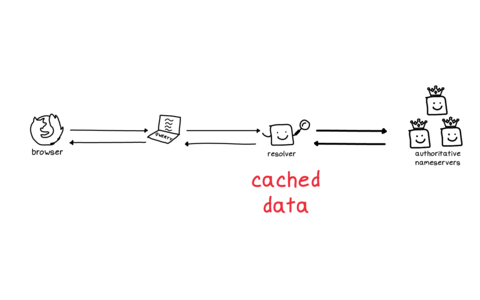

You have your browser on the left. And over on the right there's the authoritative nameservers, the source of truth of where the DNS records for a domain live.

In the middle, there's a function that you call and a cache. So you have browser, function, cache, source of truth.

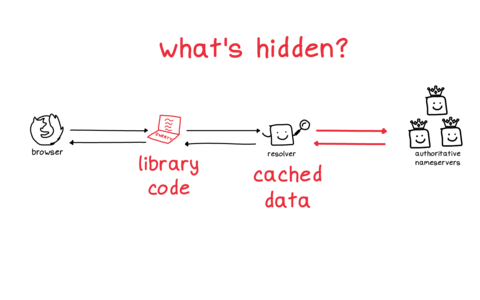

One problem is that there are a lot of things in this diagram that are totally hidden from you.

The library code that you're using where you make a DNS request -- there are a lot of different libraries you could be using, and it's not straightforward to figure out which one is being used. That was the source of some of my confusion.

There's a cache which has a bunch of cached data. That's invisible to you, you can't inspect it easily and you have no control over it. that

And there's a conversation between the cache and the source of truth, these two red arrows which also you can't see at all.

So this is kind of tough! How are you supposed to develop an intuition for a system when it's mostly things that are completely hidden from you? Feels like a lot to expect.

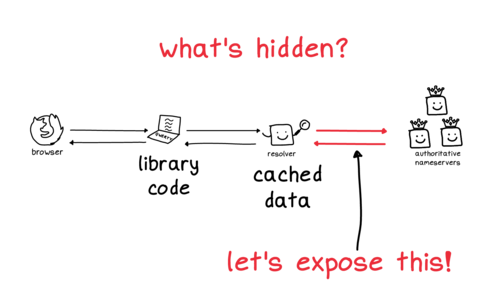

So: let's talk about these red arrows on the right.

We have our cache and then we have the source of truth. This conversation is normally hidden from you because you often don't control either of these servers. Usually they're too busy doing high-performance computing to report to you what they're doing.

But I thought: anyone can write an authoritative nameserver! In particular, I could write one that reports back every single message that it receives to its users. So, with my friend Marie, we wrote a little DNS server.

(demo of messwithdns.net)

This is called Mess With DNS. The idea is I have a domain name and you

can do whatever you want with it. We're going to make a DNS record called

strangeloop, and we're going to make a CNAME record pointing at

orange.jvns.ca, which is just a picture of an orange. Because I

like oranges.

And then over here, every time a request comes in from a resolver, this will -- this will report back what happened. So, if we click on this link, we can see -- a Canadian DNS resolver, which is apparently what my browser is configured to use, is requesting an IPv4 record and an IPv6 record, A and AAAA.

(at this point in the demo everyone in the audience starts visiting the link and it gets a bit chaotic, it's very funny)So the trick here is to find ways to show people parts of what the computer is doing that are normally hidden.

Another great example of showing things that are hidden is this website called float.exposed by Bartosz Ciechanowski who makes a lot of incredible visualizations.

So if you look at this 32-bit floating point number and click the "up" button on the significand, it'll show you the next floating point number, which is 2 more. And then as you make the number bigger and bigger (by increasing the exponent), you can see that the floating point numbers get further and further apart.

Anyway, this is not a talk about floating point. I could do an entire talk about this site and how we can use it to see how floating point works, but that's not this talk.

Another thing that makes DNS confusing is that it's a giant distributed system -- maybe you're confused because there are 5 million computers involved (really, more!). Most of which you have no control over, and some are doing not what they're supposed to do.

So that's another trick for understanding why things are hard, check to see if there are actually 5 million computers involved.

So what else is hard about DNS?

We've talked about how most of the system is hidden from you, and about how it's a big distributed system.

One of the hidden things I talked about was: the resolver has cached data, right? And you might be curious about whether a certain domain name is cached or not by your resolver right now.

Just to understand what's happening: am I getting this result because it was cached? What's the deal?

I said this was hidden, but there are a couple of ways to query a resolver to see what it has cached, and I want to show you one of them.

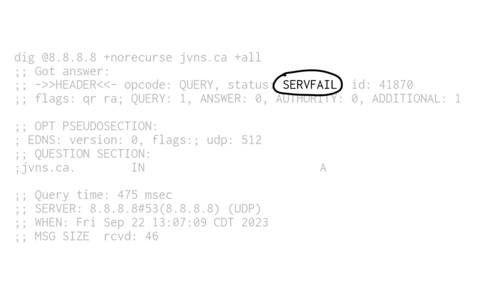

dig, and

it has a flag called +norecurse. You can use it to query a

resolver and ask it to only return results it already has cached.

With dig +norecurse jvns.ca, I'm kind of asking -- how popular is my website? Is it popular enough that someone has visited it in the last 5 minutes?

Because my records are not cached for that long, only for 5 minutes.

But when I look at this response, I feel like "please! What is all this?"

And when I show newcomers this output, they often respond by saying "wow, that's complicated, this DNS thing must be really complicated". But really this is just not a great output format, I think someone just made some relatively arbitrary choices about how to print this stuff out in the 90s and it's stayed that way ever since.

So a bad output format can mislead newcomers into thinking that something is more complicated than it actually is.

One of my favorite tricks, I call eraser eyes.

Because when I look at that output, I'm not looking at all of it, I'm just looking at a few things. My eyes are ignoring the rest of it.

When I look at the output, this is what I see: it says SERVFAIL.

That's the DNS response code.

Which as I understand it is a very unintuitive way of it saying, "I do not have that in my cache". So nobody has asked that resolver about my domain name in the last 5 minutes, which isn't very surprising.

I've learned so much from people doing a little demo of a tool, and showing how they use it and which parts of the output or UI they pay attention to, and which parts they ignore.

Becuase usually we ignore most of what's on our screens!

I really love to use dig even though it's a little hairy because

it has a lot of features (I don't know of another DNS debugging that supports this

+norecurse trick), it's everywhere, and it hasn't changed in a

long time. And I know if I learn its weird output format once I can know that

forever. Stability is really valuable to me.

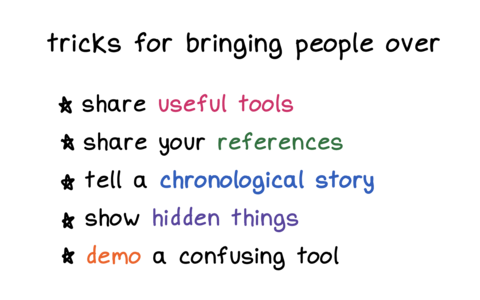

We've talked about some tricks I use to bring people over, like:

- sharing useful tools

- sharing references

- telling a chronological story of what happens on your computer

- turning a big list into a small list of the things you actually use

- showing the hidden things

- demoing a confusing tool and telling folks which parts I pay attention to

When I practiced this talk, I got some feedback from people saying "julia! I don't do those things! I don't have a blog, and I'm not going to start one!"

And it's true that most people are probably not going to start programming blogs.

But I really don't think you need to have a public presence on the internet to tell the people around you a little bit about how you use computers and how you understand them.

My experience is that a lot of people (who do not have blogs!) have helped me understand how computers work and have shared little pieces of their experience with computers with me.

I've learned a lot from my friends and my coworkers and honestly a lot of random strangers on the Internet too. I'm pretty sure some of you here today have helped me over the years, maybe on Twitter or Mastodon.

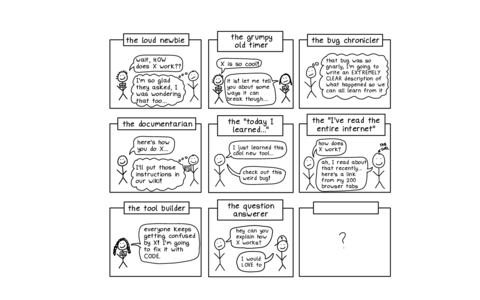

So I want to talk about some archetypes of helpful people

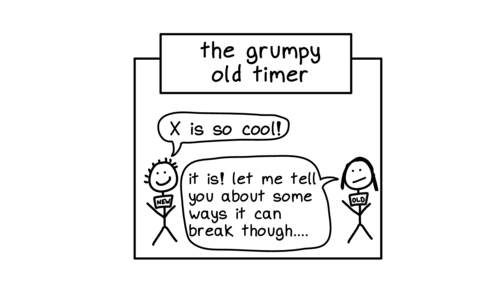

One kind of person who has really helped me is the grumpy old-timer. I'll say "this is so cool". And they'll reply yes, however, let me tell you some stories of how this has gone wrong in my life.

And those stories have sometimes helped spare me some suffering.

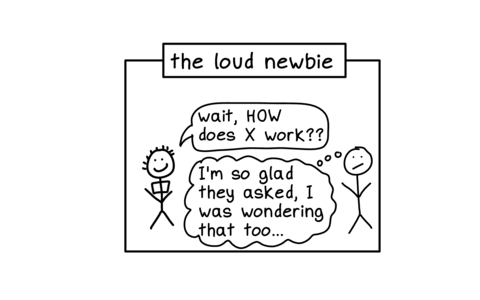

We have the loud newbie, who asks questions like "wait, how does that work?" And then everyone else feels relieved -- "oh, thank god. It's not just me."

I think it's especially valuable when the person who takes the "loud newbie" role is actually a pretty senior developer. Because when you're more secure in your position, it's easier to put yourself out there and say "uh, I don't get this" because nobody is going to judge you for that and think you're incompetent.

And then other people who feel more like they might be judged for not knowing something can ride along on your coattails.

Then we have the bug chronicler. Who decides "ok, that bug. This can never happen again".

"I'm gonna make sure we understand what happened. Because I want this to end now."

And much like when debugging a computer program, when you have a bug, you want to understand why the bug is happening if you're gonna fix it.

If we're all struggling with the same things together for the same reasons, if we can figure out what those reasons are, we can do a better job of fixing them.

- a giant pile of trivia and gotchas.

- or maybe there's 20 million lines of code somewhere.

- Maybe a big part of the system is being hidden from you.

- Maybe the tool's output is extremely confusing and no UI designer has ever worked on improving it

And that's all I have for you. Thank you.

I brought some zines to the conference, if you come to the signing later on you can get one.

some thanks

This was the last ever Strange Loop and I’m really grateful to Alex Miller and the whole organizing team for making such an incredible conference for so many years. Strange Loop accepted one of my first talks (you can be a kernel hacker) 9 years ago when I had almost no track record as a speaker so I owe a lot to them.

Thanks to Sumana for coming up with the idea for this talk, and to Marie, Danie, Kamal, Alyssa, and Maya for listening to rough drafts of it and helping make it better, and to Dolly, Jesse, and Marco for some of the conversations I mentioned.

Also after the conference Nick Fagerland wrote a nice post with thoughts on why git is hard in response to my “I don’t know why git is hard” comment and I really appreciated it. It had some new-to-me ideas and I’d love to read more analyses like that.

In a git repository, where do your files live?

Hello! I was talking to a friend about how git works today, and we got onto the

topic – where does git store your files? We know that it’s in your .git

directory, but where exactly in there are all the versions of your old files?

For example, this blog is in a git repository, and it contains a file called

content/post/2019-06-28-brag-doc.markdown. Where is that in my .git folder?

And where are the old versions of that file? Let’s investigate by writing some

very short Python programs.

git stores files in .git/objects

Every previous version of every file in your repository is in .git/objects.

For example, for this blog, .git/objects contains 2700 files.

$ find .git/objects/ -type f | wc -l

2761

note: .git/objects actually has more information than “every previous version

of every file in your repository”, but we’re not going to get into that just yet

Here’s a very short Python program

(find-git-object.py) that

finds out where any given file is stored in .git/objects.

import hashlib

import sys

def object_path(content):

header = f"blob {len(content)}\0"

data = header.encode() + content

digest = hashlib.sha1(data).hexdigest()

return f".git/objects/{digest[:2]}/{digest[2:]}"

with open(sys.argv[1], "rb") as f:

print(object_path(f.read()))

What this does is:

- read the contents of the file

- calculate a header (

blob 16673\0) and combine it with the contents - calculate the sha1 sum (

e33121a9af82dd99d6d706d037204251d41d54in this case) - translate that sha1 sum into a path (

.git/objects/e3/3121a9af82dd99d6d706d037204251d41d54)

We can run it like this:

$ python3 find-git-object.py content/post/2019-06-28-brag-doc.markdown

.git/objects/8a/e33121a9af82dd99d6d706d037204251d41d54

jargon: “content addressed storage”

The term for this storage strategy (where the filename of an object in the database is the same as the hash of the file’s contents) is “content addressed storage”.

One neat thing about content addressed storage is that if I have two files (or

50 files!) with the exact same contents, that doesn’t take up any extra space

in Git’s database – if the hash of the contents is aabbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbb, they’ll both be stored in .git/objects/aa/bbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbb.