Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Migrating Mess With DNS to use PowerDNS

About 3 years ago, I announced Mess With DNS in this blog post, a playground where you can learn how DNS works by messing around and creating records.

I wasn’t very careful with the DNS implementation though (to quote the release blog post: “following the DNS RFCs? not exactly”), and people started reporting problems that eventually I decided that I wanted to fix.

the problems

Some of the problems people have reported were:

- domain names with underscores weren’t allowed, even though they should be

- If there was a CNAME record for a domain name, it allowed you to create other records for that domain name, even if it shouldn’t

- you could create 2 different CNAME records for the same domain name, which shouldn’t be allowed

- no support for the SVCB or HTTPS record types, which seemed a little complex to implement

- no support for upgrading from UDP to TCP for big responses

And there are certainly more issues that nobody got around to reporting, for example that if you added an NS record for a subdomain to delegate it, Mess With DNS wouldn’t handle the delegation properly.

the solution: PowerDNS

I wasn’t sure how to fix these problems for a long time – technically I could have started addressing them individually, but it felt like there were a million edge cases and I’d never get there.

But then one day I was chatting with someone else who was working on a DNS server and they said they were using PowerDNS: an open source DNS server with an HTTP API!

This seemed like an obvious solution to my problems – I could just swap out my own crappy DNS implementation for PowerDNS.

There were a couple of challenges I ran into when setting up PowerDNS that I’ll talk about here. I really don’t do a lot of web development and I think I’ve never built a website that depends on a relatively complex API before, so it was a bit of a learning experience.

challenge 1: getting every query made to the DNS server

One of the main things Mess With DNS does is give you a live view of every DNS query it receives for your subdomain, using a websocket. To make this work, it needs to intercept every DNS query before they it gets sent to the PowerDNS DNS server:

There were 2 options I could think of for how to intercept the DNS queries:

- dnstap:

dnsdist(a DNS load balancer from the PowerDNS project) has support for logging all DNS queries it receives using dnstap, so I could put dnsdist in front of PowerDNS and then log queries that way - Have my Go server listen on port 53 and proxy the queries myself

I originally implemented option #1, but for some reason there was a 1 second delay before every query got logged. I couldn’t figure out why, so I implemented my own very simple proxy instead.

challenge 2: should the frontend have direct access to the PowerDNS API?

The frontend used to have a lot of DNS logic in it – it converted emoji domain

names to ASCII using punycode, had a lookup table to convert numeric DNS query

types (like 1) to their human-readable names (like A), did a little bit of

validation, and more.

Originally I considered keeping this pattern and just giving the frontend (more or less) direct access to the PowerDNS API to create and delete, but writing even more complex code in Javascript didn’t feel that appealing to me – I don’t really know how to write tests in Javascript and it seemed like it wouldn’t end well.

So I decided to take all of the DNS logic out of the frontend and write a new DNS API for managing records, shaped something like this:

GET /recordsDELETE /records/<ID>DELETE /records/(delete all records for a user)POST /records/(create record)POST /records/<ID>(update record)

This meant that I could actually write tests for my code, since the backend is in Go and I do know how to write tests in Go.

what I learned: it’s okay for an API to duplicate information

I had this idea that APIs shouldn’t return duplicate information – for example if I get a DNS record, it should only include a given piece of information once.

But I ran into a problem with that idea when displaying MX records: an MX record has 2 fields, “preference”, and “mail server”. And I needed to display that information in 2 different ways on the frontend:

- In a form, where “Preference” and “Mail Server” are 2 different form fields (like

10andmail.example.com) - In a summary view, where I wanted to just show the record (

10 mail.example.com)

This is kind of a small problem, but it came up in a few different places.

I talked to my friend Marco Rogers about this, and based on some advice from him I realized that I could return the same information in the API in 2 different ways! Then the frontend just has to display it. So I started just returning duplicate information in the API, something like this:

{

values: {'Preference': 10, 'Server': 'mail.example.com'},

content: '10 mail.example.com',

...

}

I ended up using this pattern in a couple of other places where I needed to display the same information in 2 different ways and it was SO much easier.

I think what I learned from this is that if I’m making an API that isn’t intended for external use (there are no users of this API other than the frontend!), I can tailor it very specifically to the frontend’s needs and that’s okay.

challenge 3: what’s a record’s ID?

In Mess With DNS (and I think in most DNS user interfaces!), you create, add, and delete records.

But that’s not how the PowerDNS API works. In PowerDNS, you create a zone, which is made of record sets. Records don’t have any ID in the API at all.

I ended up solving this by generate a fake ID for each records which is made of:

- its name

- its type

- and its content (base64-encoded)

For example one record’s ID is brooch225.messwithdns.com.|NS|bnMxLm1lc3N3aXRoZG5zLmNvbS4=

Then I can search through the zone and find the appropriate record to update it.

This means that if you update a record then its ID will change which isn’t usually what I want in an ID, but that seems fine.

challenge 4: making clear error messages

I think the error messages that the PowerDNS API returns aren’t really intended to be shown to end users, for example:

Name 'new\032site.island358.messwithdns.com.' contains unsupported characters(this error encodes the space as\032, which is a bit disorienting if you don’t know that the space character is 32 in ASCII)RRset test.pear5.messwithdns.com. IN CNAME: Conflicts with pre-existing RRset(this talks about RRsets, which aren’t a concept that the Mess With DNS UI has at all)Record orange.beryl5.messwithdns.com./A '1.2.3.4$': Parsing record content (try 'pdnsutil check-zone'): unable to parse IP address, strange character: $(mentions “pdnsutil”, a utility which Mess With DNS’s users don’t have access to in this context)

I ended up handling this in two ways:

- Do some initial basic validation of values that users enter (like IP addresses), so I can just return errors like

Invalid IPv4 address: "1.2.3.4$ - If that goes well, send the request to PowerDNS and if we get an error back, then do some hacky translation of those messages to make them clearer.

Sometimes users will still get errors from PowerDNS directly, but I added some logging of all the errors that users see, so hopefully I can review them and add extra translations if there are other common errors that come up.

I think what I learned from this is that if I’m building a user-facing application on top of an API, I need to be pretty thoughtful about how I resurface those errors to users.

challenge 5: setting up SQLite

Previously Mess With DNS was using a Postgres database. This was problematic

because I only gave the Postgres machine 256MB of RAM, which meant that the

database got OOM killed almost every single day. I never really worked out

exactly why it got OOM killed every day, but that’s how it was. I spent some

time trying to tune Postgres’ memory usage by setting the max connections /

work-mem / maintenance-work-mem and it helped a bit but didn’t solve the

problem.

So for this refactor I decided to use SQLite instead, because the website doesn’t really get that much traffic. There are some choices involved with using SQLite, and I decided to:

- Run

db.SetMaxOpenConns(1)to make sure that we only open 1 connection to the database at a time, to preventSQLITE_BUSYerrors from two threads trying to access the database at the same time (just setting WAL mode didn’t work) - Use separate databases for each of the 3 tables (users, records, and requests) to reduce contention. This maybe isn’t really necessary, but there was no reason I needed the tables to be in the same database so I figured I’d set up separate databases to be safe.

- Use the cgo-free modernc.org/sqlite, which translates SQLite’s source code to Go. I might switch to a more “normal” sqlite implementation instead at some point and use cgo though. I think the main reason I prefer to avoid cgo is that cgo has landed me with difficult-to-debug errors in the past.

- use WAL mode

I still haven’t set up backups, though I don’t think my Postgres database had backups either. I think I’m unlikely to use litestream for backups – Mess With DNS is very far from a critical application, and I think daily backups that I could recover from in case of a disaster are more than good enough.

challenge 6: upgrading Vue & managing forms

This has nothing to do with PowerDNS but I decided to upgrade Vue.js from version 2 to 3 as part of this refresh. The main problem with that is that the form validation library I was using (FormKit) completely changed its API between Vue 2 and Vue 3, so I decided to just stop using it instead of learning the new API.

I ended up switching to some form validation tools that are built into the

browser like required and oninvalid (here’s the code).

I think it could use some of improvement, I still don’t understand forms very well.

challenge 7: managing state in the frontend

This also has nothing to do with PowerDNS, but when modifying the frontend I realized that my state management in the frontend was a mess – in every place where I made an API request to the backend, I had to try to remember to add a “refresh records” call after that in every place that I’d modified the state and I wasn’t always consistent about it.

With some more advice from Marco, I ended up implementing a single global state management store which stores all the state for the application, and which lets me create/update/delete records.

Then my components can just call store.createRecord(record), and the store

will automatically resynchronize all of the state as needed.

challenge 8: sequencing the project

This project ended up having several steps because I reworked the whole integration between the frontend and the backend. I ended up splitting it into a few different phases:

- Upgrade Vue from v2 to v3

- Make the state management store

- Implement a different backend API, move a lot of DNS logic out of the frontend, and add tests for the backend

- Integrate PowerDNS

I made sure that the website was (more or less) 100% working and then deployed it in between phases, so that the amount of changes I was managing at a time stayed somewhat under control.

the new website is up now!

I released the upgraded website a few days ago and it seems to work! The PowerDNS API has been great to work on top of, and I’m relieved that there’s a whole class of problems that I now don’t have to think about at all, other than potentially trying to make the error messages from PowerDNS a little clearer. Using PowerDNS has fixed a lot of the DNS issues that folks have reported in the last few years and it feels great.

If you run into problems with the new Mess With DNS I’d love to hear about them here.

Go structs are copied on assignment (and other things about Go I'd missed)

I’ve been writing Go pretty casually for years – the backends for all of my playgrounds (nginx, dns, memory, more DNS) are written in Go, but many of those projects are just a few hundred lines and I don’t come back to those codebases much.

I thought I more or less understood the basics of the language, but this week I’ve been writing a lot more Go than usual while working on some upgrades to Mess with DNS, and ran into a bug that revealed I was missing a very basic concept!

Then I posted about this on Mastodon and someone linked me to this very cool site (and book) called 100 Go Mistakes and How To Avoid Them by Teiva Harsanyi. It just came out in 2022 so it’s relatively new.

I decided to read through the site to see what else I was missing, and found a couple of other misconceptions I had about Go. I’ll talk about some of the mistakes that jumped out to me the most, but really the whole 100 Go Mistakes site is great and I’d recommend reading it.

Here’s the initial mistake that started me on this journey:

mistake 1: not understanding that structs are copied on assignment

Let’s say we have a struct:

type Thing struct {

Name string

}

and this code:

thing := Thing{"record"}

other_thing := thing

other_thing.Name = "banana"

fmt.Println(thing)

This prints “record” and not “banana” (play.go.dev link), because thing is copied when you

assign it to other_thing.

the problem this caused me: ranges

The bug I spent 2 hours of my life debugging last week was effectively this code (play.go.dev link):

type Thing struct {

Name string

}

func findThing(things []Thing, name string) *Thing {

for _, thing := range things {

if thing.Name == name {

return &thing

}

}

return nil

}

func main() {

things := []Thing{Thing{"record"}, Thing{"banana"}}

thing := findThing(things, "record")

thing.Name = "gramaphone"

fmt.Println(things)

}

This prints out [{record} {banana}] – because findThing returned a copy, we didn’t change the name in the original array.

This mistake is #30 in 100 Go Mistakes.

I fixed the bug by changing it to something like this (play.go.dev link), which returns a reference to the item in the array we’re looking for instead of a copy.

func findThing(things []Thing, name string) *Thing {

for i := range things {

if things[i].Name == name {

return &things[i]

}

}

return nil

}

why didn’t I realize this?

When I learned that I was mistaken about how assignment worked in Go I was really taken aback, like – it’s such a basic fact about the language works! If I was wrong about that then what ELSE am I wrong about in Go????

My best guess for what happened is:

- I’ve heard for my whole life that when you define a function, you need to think about whether its arguments are passed by reference or by value

- So I’d thought about this in Go, and I knew that if you pass a struct as a value to a function, it gets copied – if you want to pass a reference then you have to pass a pointer

- But somehow it never occurred to me that you need to think about the same

thing for assignments, perhaps because in most of the other languages I

use (Python, JS, Java) I think everything is a reference anyway. Except for

in Rust, where you do have values that you make copies of but I think most of the time I had to run

.clone()explicitly. (though apparently structs will be automatically copied on assignment if the struct implements theCopytrait) - Also obviously I just don’t write that much Go so I guess it’s never come up.

mistake 2: side effects appending slices (#25)

When you subset a slice with x[2:3], the original slice and the sub-slice

share the same backing array, so if you append to the new slice, it can

unintentionally change the old slice:

For example, this code prints [1 2 3 555 5] (code on play.go.dev)

x := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

y := x[2:3]

y = append(y, 555)

fmt.Println(x)

I don’t think this has ever actually happened to me, but it’s alarming and I’m very happy to know about it.

Apparently you can avoid this problem by changing y := x[2:3] to y := x[2:3:3], which restricts the new slice’s capacity so that appending to it

will re-allocate a new slice. Here’s some code on play.go.dev that does that.

mistake 3: not understanding the different types of method receivers (#42)

This one isn’t a “mistake” exactly, but it’s been a source of confusion for me and it’s pretty simple so I’m glad to have it cleared up.

In Go you can declare methods in 2 different ways:

func (t Thing) Function()(a “value receiver”)func (t *Thing) Function()(a “pointer receiver”)

My understanding now is that basically:

- If you want the method to mutate the struct

t, you need a pointer receiver. - If you want to make sure the method doesn’t mutate the struct

t, use a value receiver.

Explanation #42 has a bunch of other interesting details though. There’s definitely still something I’m missing about value vs pointer receivers (I got a compile error related to them a couple of times in the last week that I still don’t understand), but hopefully I’ll run into that error again soon and I can figure it out.

more interesting things I noticed

Some more notes from 100 Go Mistakes:

- apparently you can name the outputs of your function (#43), though that can have issues (#44) and I’m not sure I want to

- apparently you can put tests in a different package (#90) to ensure that you only use the package’s public interfaces, which seems really useful

- there are a lots of notes about how to use contexts, channels, goroutines, mutexes, sync.WaitGroup, etc. I’m sure I have something to learn about all of those but today is not the day I’m going to learn them.

Also there are some things that have tripped me up in the past, like:

- forgetting the return statement after replying to an HTTP request (#80)

- not realizing the httptest package exists (#88)

this “100 common mistakes” format is great

I really appreciated this “100 common mistakes” format – it made it really easy for me to skim through the mistakes and very quickly mentally classify them into:

- yep, I know that

- not interested in that one right now

- WOW WAIT I DID NOT KNOW THAT, THAT IS VERY USEFUL!!!!

It looks like “100 Common Mistakes” is a series of books from Manning and they also have “100 Java Mistakes” and an upcoming “100 SQL Server Mistakes”.

Also I enjoyed what I’ve read of Effective Python by Brett Slatkin, which has a similar “here are a bunch of short Python style tips” structure where you can quickly skim it and take what’s useful to you. There’s also Effective C++, Effective Java, and probably more.

some other Go resources

other resources I’ve appreciated:

- Go by example for basic syntax

- go.dev/play

- obviously https://pkg.go.dev for documentation about literally everything

- staticcheck seems like a useful linter – for example I just started using it to tell me when I’ve forgotten to handle an error

- apparently golangci-lint includes a bunch of different linters

Entering text in the terminal is complicated

The other day I asked what folks on Mastodon find confusing about working in the terminal, and one thing that stood out to me was “editing a command you already typed in”.

This really resonated with me: even though entering some text and editing it is

a very “basic” task, it took me maybe 15 years of using the terminal every

single day to get used to using Ctrl+A to go to the beginning of the line (or

Ctrl+E for the end – I think I used Home/End instead).

So let’s talk about why entering text might be hard! I’ll also share a few tips that I wish I’d learned earlier.

it’s very inconsistent between programs

A big part of what makes entering text in the terminal hard is the inconsistency between how different programs handle entering text. For example:

- some programs (

cat,nc,git commit --interactive, etc) don’t support using arrow keys at all: if you press arrow keys, you’ll just see^[[D^[[D^[[C^[[C^ - many programs (like

irb,python3on a Linux machine and many many more) use thereadlinelibrary, which gives you a lot of basic functionality (history, arrow keys, etc) - some programs (like

/usr/bin/python3on my Mac) do support very basic features like arrow keys, but not other features likeCtrl+leftor reverse searching withCtrl+R - some programs (like the

fishshell oripython3ormicroorvim) have their own fancy system for accepting input which is totally custom

So there’s a lot of variation! Let’s talk about each of those a little more.

mode 1: the baseline

First, there’s “the baseline” – what happens if a program just accepts text by

calling fgets() or whatever and doing absolutely nothing else to provide a

nicer experience. Here’s what using these tools typically looks for me – If I

start the version of dash installed on

my machine (a pretty minimal shell) press the left arrow keys, it just prints

^[[D to the terminal.

$ ls l-^[[D^[[D^[[D

At first it doesn’t seem like all of these “baseline” tools have much in common, but there are actually a few features that you get for free just from your terminal, without the program needing to do anything special at all.

The things you get for free are:

- typing in text, obviously

- backspace

Ctrl+W, to delete the previous wordCtrl+U, to delete the whole line- a few other things unrelated to text editing (like

Ctrl+Cto interrupt the process,Ctrl+Zto suspend, etc)

This is not great, but it means that if you want to delete a word you

generally can do it with Ctrl+W instead of pressing backspace 15 times, even

if you’re in an environment which is offering you absolutely zero features.

You can get a list of all the ctrl codes that your terminal supports with stty -a.

mode 2: tools that use readline

The next group is tools that use readline! Readline is a GNU library to make entering text more pleasant, and it’s very widely used.

My favourite readline keyboard shortcuts are:

Ctrl+E(orEnd) to go to the end of the lineCtrl+A(orHome) to go to the beginning of the lineCtrl+left/right arrowto go back/forward 1 word- up arrow to go back to the previous command

Ctrl+Rto search your history

And you can use Ctrl+W / Ctrl+U from the “baseline” list, though Ctrl+U

deletes from the cursor to the beginning of the line instead of deleting the

whole line. I think Ctrl+W might also have a slightly different definition of

what a “word” is.

There are a lot more (here’s a full list), but those are the only ones that I personally use.

The bash shell is probably the most famous readline user (when you use

Ctrl+R to search your history in bash, that feature actually comes from

readline), but there are TONS of programs that use it – for example psql,

irb, python3, etc.

tip: you can make ANYTHING use readline with rlwrap

One of my absolute favourite things is that if you have a program like nc

without readline support, you can just run rlwrap nc to turn it into a

program with readline support!

This is incredible and makes a lot of tools that are borderline unusable MUCH more pleasant to use. You can even apparently set up rlwrap to include your own custom autocompletions, though I’ve never tried that.

some reasons tools might not use readline

I think reasons tools might not use readline might include:

- the program is very simple (like

catornc) and maybe the maintainers don’t want to bring in a relatively large dependency - license reasons, if the program’s license is not GPL-compatible – readline is GPL-licensed, not LGPL

- only a very small part of the program is interactive, and maybe readline

support isn’t seen as important. For example

githas a few interactive features (likegit add -p), but not very many, and usually you’re just typing a single character likeyorn– most of the time you need to really type something significant in git, it’ll drop you into a text editor instead.

For example idris2 says they don’t use readline

to keep dependencies minimal and suggest using rlwrap to get better

interactive features.

how to know if you’re using readline

The simplest test I can think of is to press Ctrl+R, and if you see:

(reverse-i-search)`':

then you’re probably using readline. This obviously isn’t a guarantee (some

other library could use the term reverse-i-search too!), but I don’t know of

another system that uses that specific term to refer to searching history.

the readline keybindings come from Emacs

Because I’m a vim user, It took me a very long time to understand where these

keybindings come from (why Ctrl+A to go to the beginning of a line??? so

weird!)

My understanding is these keybindings actually come from Emacs – Ctrl+A and

Ctrl+E do the same thing in Emacs as they do in Readline and I assume the

other keyboard shortcuts mostly do as well, though I tried out Ctrl+W and

Ctrl+U in Emacs and they don’t do the same thing as they do in the terminal

so I guess there are some differences.

There’s some more history of the Readline project here.

mode 3: another input library (like libedit)

On my Mac laptop, /usr/bin/python3 is in a weird middle ground where it

supports some readline features (for example the arrow keys), but not the

other ones. For example when I press Ctrl+left arrow, it prints out ;5D,

like this:

$ python3

>>> importt subprocess;5D

Folks on Mastodon helped me figure out that this is because in the default

Python install on Mac OS, the Python readline module is actually backed by

libedit, which is a similar library which has fewer features, presumably

because Readline is GPL licensed.

Here’s how I was eventually able to figure out that Python was using libedit on my system:

$ python3 -c "import readline; print(readline.__doc__)"

Importing this module enables command line editing using libedit readline.

Generally Python uses readline though if you install it on Linux or through Homebrew. It’s just that the specific version that Apple includes on their systems doesn’t have readline. Also Python 3.13 is going to remove the readline dependency in favour of a custom library, so “Python uses readline” won’t be true in the future.

I assume that there are more programs on my Mac that use libedit but I haven’t looked into it.

mode 4: something custom

The last group of programs is programs that have their own custom (and sometimes much fancier!) system for editing text. This includes:

- most terminal text editors (nano, micro, vim, emacs, etc)

- some shells (like fish), for example it seems like fish supports

Ctrl+Zfor undo when typing in a command. Zsh’s line editor is called zle. - some REPLs (like

ipython), for example IPython uses the prompt_toolkit library instead of readline - lots of other programs (like

atuin)

Some features you might see are:

- better autocomplete which is more customized to the tool

- nicer history management (for example with syntax highlighting) than the default you get from readline

- more keyboard shortcuts

custom input systems are often readline-inspired

I went looking at how Atuin (a wonderful tool for searching your shell history that I started using recently) handles text input. Looking at the code and some of the discussion around it, their implementation is custom but it’s inspired by readline, which makes sense to me – a lot of users are used to those keybindings, and it’s convenient for them to work even though atuin doesn’t use readline.

prompt_toolkit (the library IPython uses) is similar – it actually supports a lot of options (including vi-like keybindings), but the default is to support the readline-style keybindings.

This is like how you see a lot of programs which support very basic vim

keybindings (like j for down and k for up). For example Fastmail supports

j and k even though most of its other keybindings don’t have much

relationship to vim.

I assume that most “readline-inspired” custom input systems have various subtle incompatibilities with readline, but this doesn’t really bother me at all personally because I’m extremely ignorant of most of readline’s features. I only use maybe 5 keyboard shortcuts, so as long as they support the 5 basic commands I know (which they always do!) I feel pretty comfortable. And usually these custom systems have much better autocomplete than you’d get from just using readline, so generally I prefer them over readline.

lots of shells support vi keybindings

Bash, zsh, and fish all have a “vi mode” for entering text. In a very unscientific poll I ran on Mastodon, 12% of people said they use it, so it seems pretty popular.

Readline also has a “vi mode” (which is how Bash’s support for it works), so by extension lots of other programs have it too.

I’ve always thought that vi mode seems really cool, but for some reason even though I’m a vim user it’s never stuck for me.

understanding what situation you’re in really helps

I’ve spent a lot of my life being confused about why a command line application I was using wasn’t behaving the way I wanted, and it feels good to be able to more or less understand what’s going on.

I think this is roughly my mental flowchart when I’m entering text at a command line prompt:

- Do the arrow keys not work? Probably there’s no input system at all, but at

least I can use

Ctrl+WandCtrl+U, and I canrlwrapthe tool if I want more features. - Does

Ctrl+Rprintreverse-i-search? Probably it’s readline, so I can use all of the readline shortcuts I’m used to, and I know I can get some basic history and press up arrow to get the previous command. - Does

Ctrl+Rdo something else? This is probably some custom input library: it’ll probably act more or less like readline, and I can check the documentation if I really want to know how it works.

Being able to diagnose what’s going on like this makes the command line feel a more predictable and less chaotic.

some things this post left out

There are lots more complications related to entering text that we didn’t talk about at all here, like:

- issues related to ssh / tmux / etc

- the

TERMenvironment variable - how different terminals (gnome terminal, iTerm, xterm, etc) have different kinds of support for copying/pasting text

- unicode

- probably a lot more

Reasons to use your shell's job control

Hello! Today someone on Mastodon asked about job control (fg, bg, Ctrl+z,

wait, etc). It made me think about how I don’t use my shell’s job

control interactively very often: usually I prefer to just open a new terminal

tab if I want to run multiple terminal programs, or use tmux if it’s over ssh.

But I was curious about whether other people used job control more often than me.

So I asked on Mastodon for reasons people use job control. There were a lot of great responses, and it even made me want to consider using job control a little more!

In this post I’m only going to talk about using job control interactively (not in scripts) – the post is already long enough just talking about interactive use.

what’s job control?

First: what’s job control? Well – in a terminal, your processes can be in one of 3 states:

- in the foreground. This is the normal state when you start a process.

- in the background. This is what happens when you run

some_process &: the process is still running, but you can’t interact with it anymore unless you bring it back to the foreground. - stopped. This is what happens when you start a process and then press

Ctrl+Z. This pauses the process: it won’t keep using the CPU, but you can restart it if you want.

“Job control” is a set of commands for seeing which processes are running in a terminal and moving processes between these 3 states

how to use job control

fgbrings a process to the foreground. It works on both stopped processes and background processes. For example, if you start a background process withcat < /dev/zero &, you can bring it back to the foreground by runningfgbgrestarts a stopped process and puts it in the background.- Pressing

Ctrl+zstops the current foreground process. jobslists all processes that are active in your terminalkillsends a signal (likeSIGKILL) to a job (this is the shell builtinkill, not/bin/kill)disownremoves the job from the list of running jobs, so that it doesn’t get killed when you close the terminalwaitwaits for all background processes to complete. I only use this in scripts though.- apparently in bash/zsh you can also just type

%2instead offg %2

I might have forgotten some other job control commands but I think those are all the ones I’ve ever used.

You can also give fg or bg a specific job to foreground/background. For example if I see this in the output of jobs:

$ jobs

Job Group State Command

1 3161 running cat < /dev/zero &

2 3264 stopped nvim -w ~/.vimkeys $argv

then I can foreground nvim with fg %2. You can also kill it with kill -9 %2, or just kill %2 if you want to be more gentle.

how is kill %2 implemented?

I was curious about how kill %2 works – does %2 just get replaced with the

PID of the relevant process when you run the command, the way environment

variables are? Some quick experimentation shows that it isn’t:

$ echo kill %2

kill %2

$ type kill

kill is a function with definition

# Defined in /nix/store/vicfrai6lhnl8xw6azq5dzaizx56gw4m-fish-3.7.0/share/fish/config.fish

So kill is a fish builtin that knows how to interpret %2. Looking at

the source code (which is very easy in fish!), it uses jobs -p %2 to expand %2

into a PID, and then runs the regular kill command.

on differences between shells

Job control is implemented by your shell. I use fish, but my sense is that the basics of job control work pretty similarly in bash, fish, and zsh.

There are definitely some shells which don’t have job control at all, but I’ve only used bash/fish/zsh so I don’t know much about that.

Now let’s get into a few reasons people use job control!

reason 1: kill a command that’s not responding to Ctrl+C

I run into processes that don’t respond to Ctrl+C pretty regularly, and it’s

always a little annoying – I usually switch terminal tabs to find and kill and

the process. A bunch of people pointed out that you can do this in a faster way

using job control!

How to do this: Press Ctrl+Z, then kill %1 (or the appropriate job number

if there’s more than one stopped/background job, which you can get from

jobs). You can also kill -9 if it’s really not responding.

reason 2: background a GUI app so it’s not using up a terminal tab

Sometimes I start a GUI program from the command line (for example with

wireshark some_file.pcap), forget to start it in the background, and don’t want it eating up my terminal tab.

How to do this:

- move the GUI program to the background by pressing

Ctrl+Zand then runningbg. - you can also run

disownto remove it from the list of jobs, to make sure that the GUI program won’t get closed when you close your terminal tab.

Personally I try to avoid starting GUI programs from the terminal if possible

because I don’t like how their stdout pollutes my terminal (on a Mac I use

open -a Wireshark instead because I find it works better but sometimes you

don’t have another choice.

reason 2.5: accidentally started a long-running job without tmux

This is basically the same as the GUI app thing – you can move the job to the background and disown it.

I was also curious about if there are ways to redirect a process’s output to a file after it’s already started. A quick search turned up this Linux-only tool which is based on nelhage’s reptyr (which lets you for example move a process that you started outside of tmux to tmux) but I haven’t tried either of those.

reason 3: running a command while using vim

A lot of people mentioned that if they want to quickly test something while

editing code in vim or another terminal editor, they like to use Ctrl+Z

to stop vim, run the command, and then run fg to go back to their editor.

You can also use this to check the output of a command that you ran before

starting vim.

I’ve never gotten in the habit of this, probably because I mostly use a GUI version of vim. I feel like I’d also be likely to switch terminal tabs and end up wondering “wait… where did I put my editor???” and have to go searching for it.

reason 4: preferring interleaved output

A few people said that they prefer to the output of all of their commands being interleaved in the terminal. This really surprised me because I usually think of having the output of lots of different commands interleaved as being a bad thing, but one person said that they like to do this with tcpdump specifically and I think that actually sounds extremely useful. Here’s what it looks like:

# start tcpdump

$ sudo tcpdump -ni any port 1234 &

tcpdump: data link type PKTAP

tcpdump: verbose output suppressed, use -v[v]... for full protocol decode

listening on any, link-type PKTAP (Apple DLT_PKTAP), snapshot length 524288 bytes

# run curl

$ curl google.com:1234

13:13:29.881018 IP 192.168.1.173.49626 > 142.251.41.78.1234: Flags [S], seq 613574185, win 65535, options [mss 1460,nop,wscale 6,nop,nop,TS val 2730440518 ecr 0,sackOK,eol], length 0

13:13:30.881963 IP 192.168.1.173.49626 > 142.251.41.78.1234: Flags [S], seq 613574185, win 65535, options [mss 1460,nop,wscale 6,nop,nop,TS val 2730441519 ecr 0,sackOK,eol], length 0

13:13:31.882587 IP 192.168.1.173.49626 > 142.251.41.78.1234: Flags [S], seq 613574185, win 65535, options [mss 1460,nop,wscale 6,nop,nop,TS val 2730442520 ecr 0,sackOK,eol], length 0

# when you're done, kill the tcpdump in the background

$ kill %1

I think it’s really nice here that you can see the output of tcpdump inline in your terminal – when I’m using tcpdump I’m always switching back and forth and I always get confused trying to match up the timestamps, so keeping everything in one terminal seems like it might be a lot clearer. I’m going to try it.

reason 5: suspend a CPU-hungry program

One person said that sometimes they’re running a very CPU-intensive program,

for example converting a video with ffmpeg, and they need to use the CPU for

something else, but don’t want to lose the work that ffmpeg already did.

You can do this by pressing Ctrl+Z to pause the process, and then run fg

when you want to start it again.

reason 6: you accidentally ran Ctrl+Z

Many people replied that they didn’t use job control intentionally, but

that they sometimes accidentally ran Ctrl+Z, which stopped whatever program was

running, so they needed to learn how to use fg to bring it back to the

foreground.

The were also some mentions of accidentally running Ctrl+S too (which stops

your terminal and I think can be undone with Ctrl+Q). My terminal totally

ignores Ctrl+S so I guess I’m safe from that one though.

reason 7: already set up a bunch of environment variables

Some folks mentioned that they already set up a bunch of environment variables that they need to run various commands, so it’s easier to use job control to run multiple commands in the same terminal than to redo that work in another tab.

reason 8: it’s your only option

Probably the most obvious reason to use job control to manage multiple processes is “because you have to” – maybe you’re in single-user mode, or on a very restricted computer, or SSH’d into a machine that doesn’t have tmux or screen and you don’t want to create multiple SSH sessions.

reason 9: some people just like it better

Some people also said that they just don’t like using terminal tabs: for instance a few folks mentioned that they prefer to be able to see all of their terminals on the screen at the same time, so they’d rather have 4 terminals on the screen and then use job control if they need to run more than 4 programs.

I learned a few new tricks!

I think my two main takeaways from thos post is I’ll probably try out job control a little more for:

- killing processes that don’t respond to Ctrl+C

- running

tcpdumpin the background with whatever network command I’m running, so I can see both of their output in the same place

New zine: How Git Works!

Hello! I’ve been writing about git on here nonstop for months, and the git zine is FINALLY done! It came out on Friday!

You can get it for $12 here: https://wizardzines.com/zines/git, or get an 14-pack of all my zines here.

Here’s the cover:

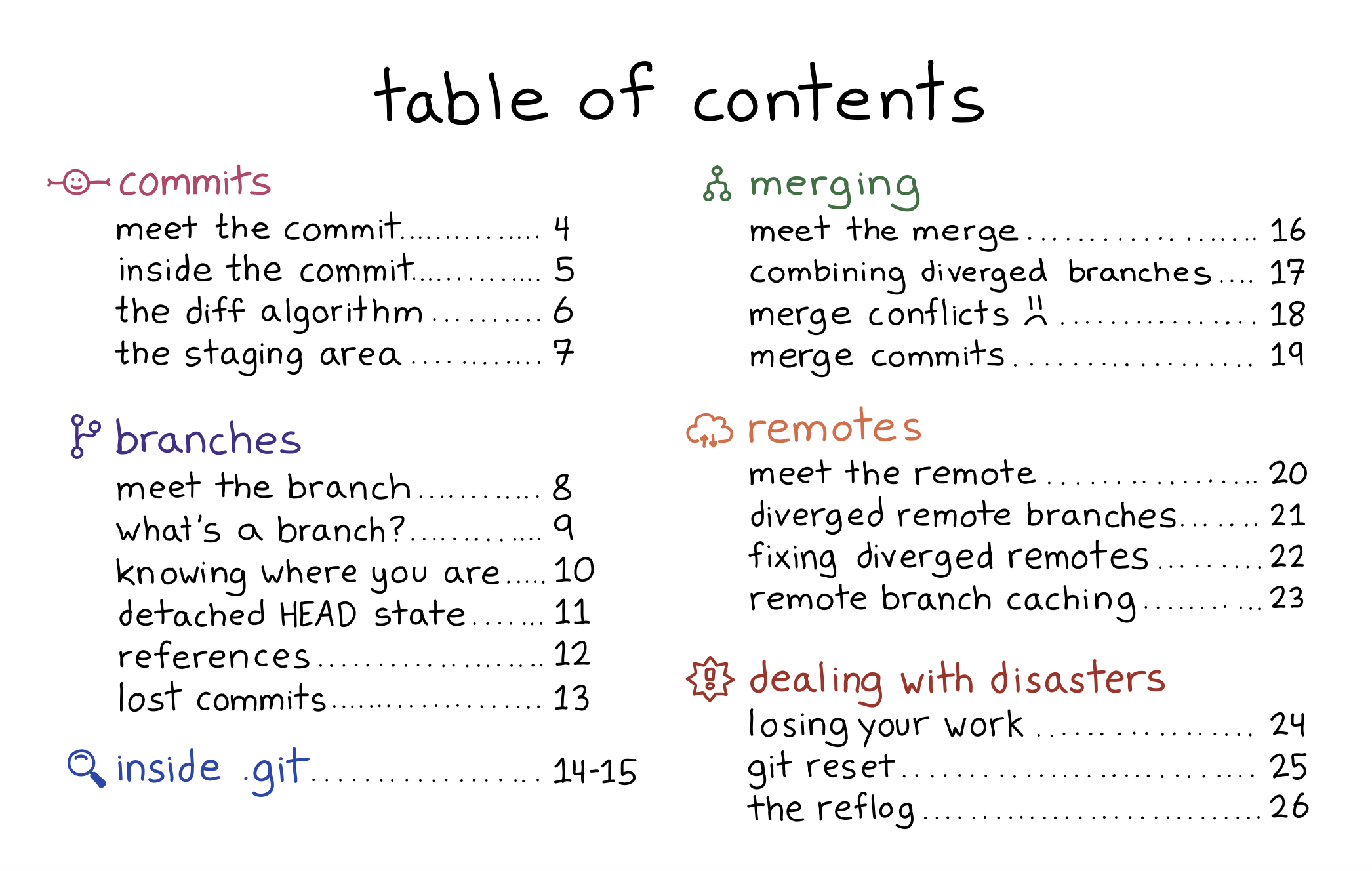

the table of contents

Here’s the table of contents:

who is this zine for?

I wrote this zine for people who have been using git for years and are still afraid of it. As always – I think it sucks to be afraid of the tools that you use in your work every day! I want folks to feel confident using git.

My goals are:

- To explain how some parts of git that initially seem scary (like “detached HEAD state”) are pretty straightforward to deal with once you understand what’s going on

- To show some parts of git you probably should be careful around. For example, the stash is one of the places in git where it’s easiest to lose your work in a way that’s incredibly annoying to recover form, and I avoid using it heavily because of that.

- To clear up a few common misconceptions about how the core parts of git (like commits, branches, and merging) work

what’s the difference between this and Oh Shit, Git!

You might be wondering – Julia! You already have a zine about git! What’s going on? Oh Shit, Git! is a set of tricks for fixing git messes. “How Git Works” explains how Git actually works.

Also, Oh Shit, Git! is the amazing Katie Sylor Miller’s concept: we made it into a zine because I was such a huge fan of her work on it.

I think they go really well together.

what’s so confusing about git, anyway?

This zine was really hard for me to write because when I started writing it, I’d been using git pretty confidently for 10 years. I had no real memory of what it was like to struggle with git.

But thanks to a huge amount of help from Marie as well as everyone who talked to me about git on Mastodon, eventually I was able to see that there are a lot of things about git that are counterintuitive, misleading, or just plain confusing. These include:

- confusing terminology (for example “fast-forward”, “reference”, or “remote-tracking branch”)

- misleading messages (for example how

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'doesn’t necessary mean that your branch is up to date with themainbranch on the origin) - uninformative output (for example how I STILL can’t reliably figure out which code comes from which branch when I’m looking at a merge conflict)

- a lack of guidance around handling diverged branches (for example how when you run

git pulland your branch has diverged from the origin, it doesn’t give you great guidance how to handle the situation) - inconsistent behaviour (for example how git’s reflogs are almost always append-only, EXCEPT for the stash, where git will delete entries when you run

git stash drop)

The more I heard from people how about how confusing they find git, the more it became clear that git really does not make it easy to figure out what its internal logic is just by using it.

handling git’s weirdnesses becomes pretty routine

The previous section made git sound really bad, like “how can anyone possibly use this thing?”.

But my experience is that after I learned what git actually means by all of its

weird error messages, dealing with it became pretty routine! I’ll see an

error: failed to push some refs to 'github.com:jvns/wizard-zines-site',

realize “oh right, probably a coworker made some changes to main since I last

ran git pull”, run git pull --rebase to incorporate their changes, and move

on with my day. The whole thing takes about 10 seconds.

Or if I see a You are in 'detached HEAD' state warning, I’ll just make sure

to run git checkout mybranch before continuing to write code. No big deal.

For me (and for a lot of folks I talk to about git!), dealing with git’s weird language can become so normal that you totally forget why anybody would even find it weird.

a little bit of internals

One of my biggest questions when writing this zine was how much to focus on

what’s in the .git directory. We ended up deciding to include a couple of

pages about internals (“inside .git”, pages 14-15), but otherwise focus more on

git’s behaviour when you use it and why sometimes git behaves in unexpected

ways.

This is partly because there are lots of great guides to git’s internals out there already (1, 2), and partly because I think even if you have read one of these guides to git’s internals, it isn’t totally obvious how to connect that information to what you actually see in git’s user interface.

For example: it’s easy to find documentation about remotes in git – for example this page says:

Remote-tracking branches […] remind you where the branches in your remote repositories were the last time you connected to them.

But even if you’ve read that, you might not realize that the statement Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'" in git status doesn’t necessarily

mean that you’re actually up to date with the remote main branch.

So in general in the zine we focus on the behaviour you see in Git’s UI, and then explain how that relates to what’s happening internally in Git.

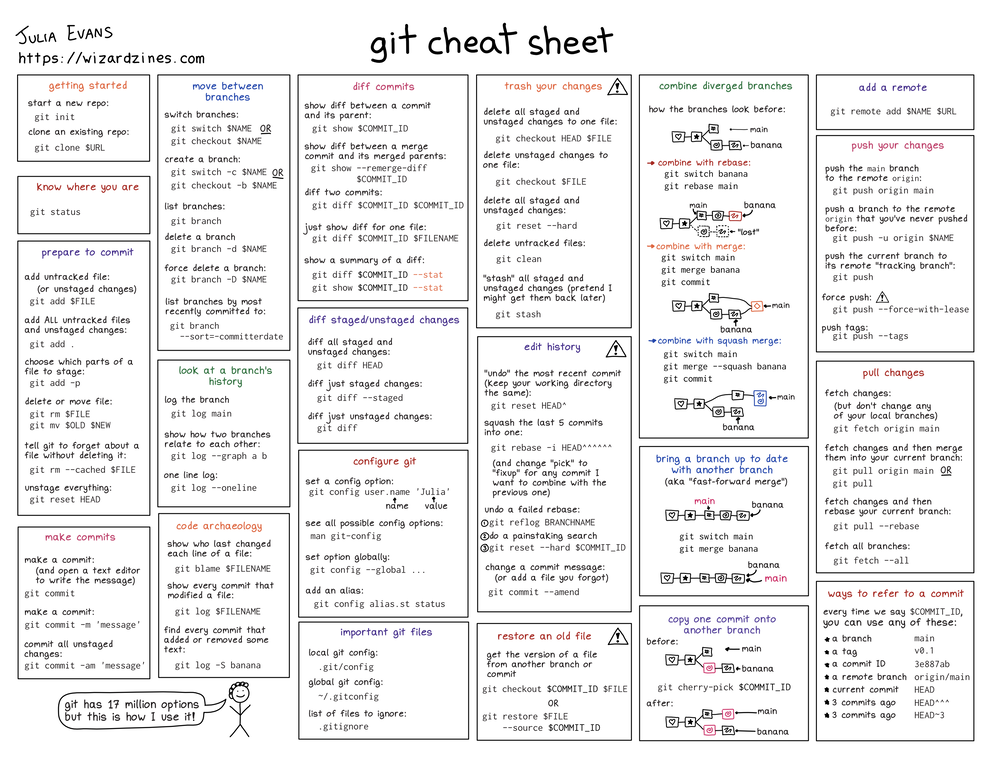

the cheat sheet

The zine also comes with a free printable cheat sheet: (click to get a PDF version)

it comes with an HTML transcript!

The zine also comes with an HTML transcript, to (hopefully) make it easier to read on a screen reader! Our Operations Manager, Lee, transcribed all of the pages and wrote image descriptions. I’d love feedback about the experience of reading the zine on a screen reader if you try it.

I really do love git

I’ve been pretty critical about git in this post, but I only write zines about technologies I love, and git is no exception.

Some reasons I love git:

- it’s fast!

- it’s backwards compatible! I learned how to use it 10 years ago and everything I learned then is still true

- there’s tons of great free Git hosting available out there (GitHub! Gitlab! a million more!), so I can easily back up all my code

- simple workflows are REALLY simple (if I’m working on a project on my own, I

can just run

git commit -am 'whatever'andgit pushover and over again and it works perfectly) - Almost every internal file in git is a pretty simple text file (or has a version which is a text file), which makes me feel like I can always understand exactly what’s going on under the hood if I want to.

I hope this zine helps some of you love it too.

people who helped with this zine

I don’t make these zines by myself!

I worked with Marie Claire LeBlanc Flanagan every morning for 8 months to write clear explanations of git.

The cover is by Vladimir Kašiković, Gersande La Flèche did copy editing, James Coglan (of the great Building Git) did technical review, our Operations Manager Lee did the transcription as well as a million other things, my partner Kamal read the zine and told me which parts were off (as he always does), and I had a million great conversations with Marco Rogers about git.

And finally, I want to thank all the beta readers! There were 66 this time which is a record! They left hundreds of comments about what was confusing, what they learned, and which of my jokes were funny. It’s always hard to hear from beta readers that a page I thought made sense is actually extremely confusing, and fixing those problems before the final version makes the zine so much better.

get the zine

Here are some links to get the zine again:

- get How Git Works

- get an 14-pack of all my zines here.

As always, you can get either a PDF version to print at home or a print version shipped to your house. The only caveat is print orders will ship in July – I need to wait for orders to come in to get an idea of how many I should print before sending it to the printer.

thank you

As always: if you’ve bought zines in the past, thank you for all your support over the years. And thanks to all of you (1000+ people!!!) who have already bought the zine in the first 3 days. It’s already set a record for most zines sold in a single day and I’ve been really blown away.