Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Using less memory to look up IP addresses in Mess With DNS

I’ve been having problems for the last 3 years or so where Mess With DNS periodically runs out of memory and gets OOM killed.

This hasn’t been a big priority for me: usually it just goes down for a few minutes while it restarts, and it only happens once a day at most, so I’ve just been ignoring. But last week it started actually causing a problem so I decided to look into it.

This was kind of winding road where I learned a lot so here’s a table of contents:

- there’s about 100MB of memory available

- the problem: OOM killing the backup script

- attempt 1: use SQLite

- attempt 2: use a trie

- attempt 3: make my array use less memory

there’s about 100MB of memory available

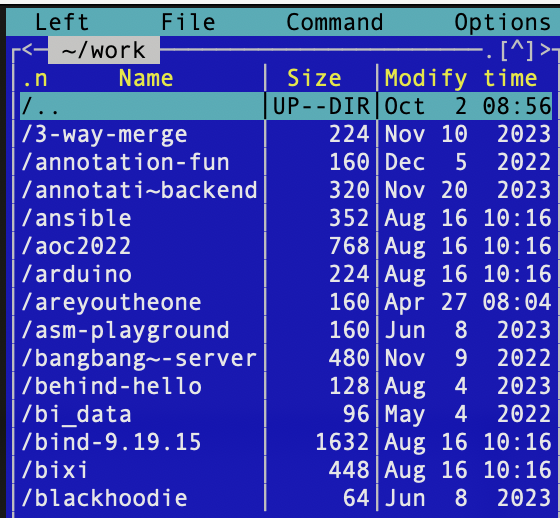

I run Mess With DNS on a VM without about 465MB of RAM, which according to

ps aux (the RSS column) is split up something like:

- 100MB for PowerDNS

- 200MB for Mess With DNS

- 40MB for hallpass

That leaves about 110MB of memory free.

A while back I set GOMEMLIMIT to 250MB to try to make sure the garbage collector ran if Mess With DNS used more than 250MB of memory, and I think this helped but it didn’t solve everything.

the problem: OOM killing the backup script

A few weeks ago I started backing up Mess With DNS’s database for the first time using restic.

This has been working okay, but since Mess With DNS operates without much extra

memory I think restic sometimes needed more memory than was available on the

system, and so the backup script sometimes got OOM killed.

This was a problem because

- backups might be corrupted sometimes

- more importantly, restic takes out a lock when it runs, and so I’d have to manually do an unlock if I wanted the backups to continue working. Doing manual work like this is the #1 thing I try to avoid with all my web services (who has time for that!) so I really wanted to do something about it.

There’s probably more than one solution to this, but I decided to try to make Mess With DNS use less memory so that there was more available memory on the system, mostly because it seemed like a fun problem to try to solve.

what’s using memory: IP addresses

I’d run a memory profile of Mess With DNS a bunch of times in the past, so I knew exactly what was using most of Mess With DNS’s memory: IP addresses.

When it starts, Mess With DNS loads this database where you can look up the

ASN of every IP address into memory, so that when it

receives a DNS query it can take the source IP address like 74.125.16.248 and

tell you that IP address belongs to GOOGLE.

This database by itself used about 117MB of memory, and a simple du told me

that was too much – the original text files were only 37MB!

$ du -sh *.tsv

26M ip2asn-v4.tsv

11M ip2asn-v6.tsv

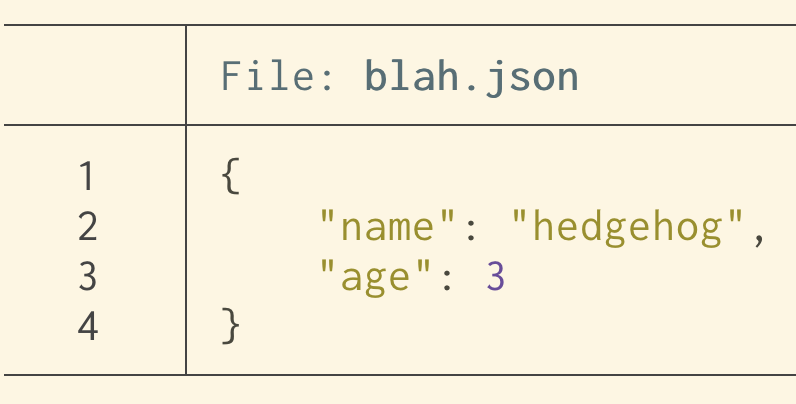

The way it worked originally is that I had an array of these:

type IPRange struct {

StartIP net.IP

EndIP net.IP

Num int

Name string

Country string

}

and I searched through it with a binary search to figure out if any of the ranges contained the IP I was looking for. Basically the simplest possible thing and it’s super fast, my machine can do about 9 million lookups per second.

attempt 1: use SQLite

I’ve been using SQLite recently, so my first thought was – maybe I can store all of this data on disk in an SQLite database, give the tables an index, and that’ll use less memory.

So I:

- wrote a quick Python script using sqlite-utils to import the TSV files into an SQLite database

- adjusted my code to select from the database instead

This did solve the initial memory goal (after a GC it now hardly used any memory at all because the table was on disk!), though I’m not sure how much GC churn this solution would cause if we needed to do a lot of queries at once. I did a quick memory profile and it seemed to allocate about 1KB of memory per lookup.

Let’s talk about the issues I ran into with using SQLite though.

problem: how to store IPv6 addresses

SQLite doesn’t have support for big integers and IPv6 addresses are 128 bits,

so I decided to store them as text. I think BLOB might have been better, I

originally thought BLOBs couldn’t be compared but the sqlite docs say they can.

I ended up with this schema:

CREATE TABLE ipv4_ranges (

start_ip INTEGER NOT NULL,

end_ip INTEGER NOT NULL,

asn INTEGER NOT NULL,

country TEXT NOT NULL,

name TEXT NOT NULL

);

CREATE TABLE ipv6_ranges (

start_ip TEXT NOT NULL,

end_ip TEXT NOT NULL,

asn INTEGER,

country TEXT,

name TEXT

);

CREATE INDEX idx_ipv4_ranges_start_ip ON ipv4_ranges (start_ip);

CREATE INDEX idx_ipv6_ranges_start_ip ON ipv6_ranges (start_ip);

CREATE INDEX idx_ipv4_ranges_end_ip ON ipv4_ranges (end_ip);

CREATE INDEX idx_ipv6_ranges_end_ip ON ipv6_ranges (end_ip);

Also I learned that Python has an ipaddress module, so I could use

ipaddress.ip_address(s).exploded to make sure that the IPv6 addresses were

expanded so that a string comparison would compare them properly.

problem: it’s 500x slower

I ran a quick microbenchmark, something like this. It printed out that it could look up 17,000 IPv6 addresses per second, and similarly for IPv4 addresses.

This was pretty discouraging – being able to look up 17k addresses per section is kind of fine (Mess With DNS does not get a lot of traffic), but I compared it to the original binary search code and the original code could do 9 million per second.

ips := []net.IP{}

count := 20000

for i := 0; i < count; i++ {

// create a random IPv6 address

bytes := randomBytes()

ip := net.IP(bytes[:])

ips = append(ips, ip)

}

now := time.Now()

success := 0

for _, ip := range ips {

_, err := ranges.FindASN(ip)

if err == nil {

success++

}

}

fmt.Println(success)

elapsed := time.Since(now)

fmt.Println("number per second", float64(count)/elapsed.Seconds())

time for EXPLAIN QUERY PLAN

I’d never really done an EXPLAIN in sqlite, so I thought it would be a fun opportunity to see what the query plan was doing.

sqlite> explain query plan select * from ipv6_ranges where '2607:f8b0:4006:0824:0000:0000:0000:200e' BETWEEN start_ip and end_ip;

QUERY PLAN

`--SEARCH ipv6_ranges USING INDEX idx_ipv6_ranges_end_ip (end_ip>?)

It looks like it’s just using the end_ip index and not the start_ip index,

so maybe it makes sense that it’s slower than the binary search.

I tried to figure out if there was a way to make SQLite use both indexes, but I couldn’t find one and maybe it knows best anyway.

At this point I gave up on the SQLite solution, I didn’t love that it was slower and also it’s a lot more complex than just doing a binary search. I felt like I’d rather keep something much more similar to the binary search.

A few things I tried with SQLite that did not cause it to use both indexes:

- using a compound index instead of two separate indexes

- running

ANALYZE - using

INTERSECTto intersect the results ofstart_ip < ?and? < end_ip. This did make it use both indexes, but it also seemed to make the query literally 1000x slower, probably because it needed to create the results of both subqueries in memory and intersect them.

attempt 2: use a trie

My next idea was to use a trie, because I had some vague idea that maybe a trie would use less memory, and I found this library called ipaddress-go that lets you look up IP addresses using a trie.

I tried using it here’s the code, but I think I was doing something wildly wrong because, compared to my naive array + binary search:

- it used WAY more memory (800MB to store just the IPv4 addresses)

- it was a lot slower to do the lookups (it could do only 100K/second instead of 9 million/second)

I’m not really sure what went wrong here but I gave up on this approach and decided to just try to make my array use less memory and stick to a simple binary search.

some notes on memory profiling

One thing I learned about memory profiling is that you can use runtime

package to see how much memory is currently allocated in the program. That’s

how I got all the memory numbers in this post. Here’s the code:

func memusage() {

runtime.GC()

var m runtime.MemStats

runtime.ReadMemStats(&m)

fmt.Printf("Alloc = %v MiB\n", m.Alloc/1024/1024)

// write mem.prof

f, err := os.Create("mem.prof")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

pprof.WriteHeapProfile(f)

f.Close()

}

Also I learned that if you use pprof to analyze a heap profile there are two

ways to analyze it: you can pass either --alloc-space or --inuse-space to

go tool pprof. I don’t know how I didn’t realize this before but

alloc-space will tell you about everything that was allocated, and

inuse-space will just include memory that’s currently in use.

Anyway I ran go tool pprof -pdf --inuse_space mem.prof > mem.pdf a lot. Also

every time I use pprof I find myself referring to my own intro to pprof, it’s probably

the blog post I wrote that I use the most often. I should add --alloc-space

and --inuse-space to it.

attempt 3: make my array use less memory

I was storing my ip2asn entries like this:

type IPRange struct {

StartIP net.IP

EndIP net.IP

Num int

Name string

Country string

}

I had 3 ideas for ways to improve this:

- There was a lot of repetition of

Nameand theCountry, because a lot of IP ranges belong to the same ASN net.IPis an[]byteunder the hood, which felt like it involved an unnecessary pointer, was there a way to inline it into the struct?- Maybe I didn’t need both the start IP and the end IP, often the ranges were consecutive so maybe I could rearrange things so that I only had the start IP

idea 3.1: deduplicate the Name and Country

I figured I could store the ASN info in an array, and then just store the index

into the array in my IPRange struct. Here are the structs so you can see what

I mean:

type IPRange struct {

StartIP netip.Addr

EndIP netip.Addr

ASN uint32

Idx uint32

}

type ASNInfo struct {

Country string

Name string

}

type ASNPool struct {

asns []ASNInfo

lookup map[ASNInfo]uint32

}

This worked! It brought memory usage from 117MB to 65MB – a 50MB savings. I felt good about this.

Here’s all of the code for that part.

how big are ASNs?

As an aside – I’m storing the ASN in a uint32, is that right? I looked in the ip2asn

file and the biggest one seems to be 401307, though there are a few lines that

say 4294901931 which is much bigger, but also are just inside the range of a

uint32. So I can definitely use a uint32.

59.101.179.0 59.101.179.255 4294901931 Unknown AS4294901931

idea 3.2: use netip.Addr instead of net.IP

It turns out that I’m not the only one who felt that net.IP was using an

unnecessary amount of memory – in 2021 the folks at Tailscale released a new

IP address library for Go which solves this and many other issues. They wrote a great blog post about it.

I discovered (to my delight) that not only does this new IP address library exist and do exactly what I want, it’s also now in the Go

standard library as netip.Addr. Switching to netip.Addr was

very easy and saved another 20MB of memory, bringing us to 46MB.

I didn’t try my third idea (remove the end IP from the struct) because I’d already been programming for long enough on a Saturday morning and I was happy with my progress.

It’s always such a great feeling when I think “hey, I don’t like this, there must be a better way” and then immediately discover that someone has already made the exact thing I want, thought about it a lot more than me, and implemented it much better than I would have.

all of this was messier in real life

Even though I tried to explain this in a simple linear way “I tried X, then I tried Y, then I tried Z”, that’s kind of a lie – I always try to take my actual debugging process (total chaos) and make it seem more linear and understandable because the reality is just too annoying to write down. It’s more like:

- try sqlite

- try a trie

- second guess everything that I concluded about sqlite, go back and look at the results again

- wait what about indexes

- very very belatedly realize that I can use

runtimeto check how much memory everything is using, start doing that - look at the trie again, maybe I misunderstood everything

- give up and go back to binary search

- look at all of the numbers for tries/sqlite again to make sure I didn’t misunderstand

A note on using 512MB of memory

Someone asked why I don’t just give the VM more memory. I could very easily afford to pay for a VM with 1GB of memory, but I feel like 512MB really should be enough (and really that 256MB should be enough!) so I’d rather stay inside that constraint. It’s kind of a fun puzzle.

a few ideas from the replies

Folks had a lot of good ideas I hadn’t thought of. Recording them as inspiration if I feel like having another Fun Performance Day at some point.

- Try Go’s unique package for the

ASNPool. Someone tried this and it uses more memory, probably because Go’s pointers are 64 bits - Try compiling with

GOARCH=386to use 32-bit pointers to sace space (maybe in combination with usingunique!) - It should be possible to store all of the IPv6 addresses in just 64 bits, because only the first 64 bits of the address are public

- Interpolation search might be faster than binary search since IP addresses are numeric

- Try the MaxMind db format with mmdbwriter or mmdbctl

- Tailscale’s art routing table package

the result: saved 70MB of memory!

I deployed the new version and now Mess With DNS is using less memory! Hooray!

A few other notes:

- lookups are a little slower – in my microbenchmark they went from 9 million lookups/second to 6 million, maybe because I added a little indirection. Using less memory and a little more CPU seemed like a good tradeoff though.

- it’s still using more memory than the raw text files do (46MB vs 37MB), I guess pointers take up space and that’s okay.

I’m honestly not sure if this will solve all my memory problems, probably not! But I had fun, I learned a few things about SQLite, I still don’t know what to think about tries, and it made me love binary search even more than I already did.

Some notes on upgrading Hugo

Warning: this is a post about very boring yakshaving, probably only of interest to people who are trying to upgrade Hugo from a very old version to a new version. But what are blogs for if not documenting one’s very boring yakshaves from time to time?

So yesterday I decided to try to upgrade Hugo. There’s no real reason to do this – I’ve been using Hugo version 0.40 to generate this blog since 2018, it works fine, and I don’t have any problems with it. But I thought – maybe it won’t be as hard as I think, and I kind of like a tedious computer task sometimes!

I thought I’d document what I learned along the way in case it’s useful to anyone else doing this very specific migration. I upgraded from Hugo v0.40 (from 2018) to v0.135 (from 2024).

Here are most of the changes I had to make:

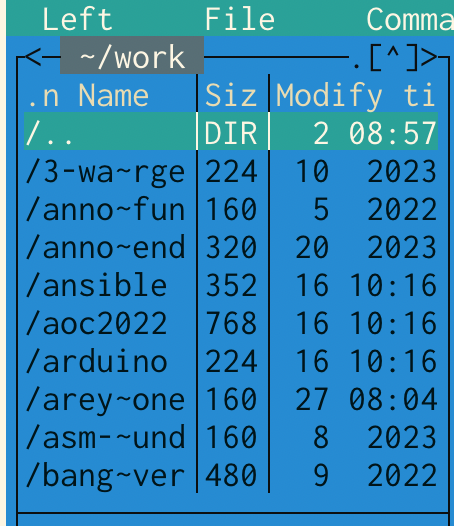

change 1: template "theme/partials/thing.html is now partial thing.html

I had to replace a bunch of instances of {{ template "theme/partials/header.html" . }} with {{ partial "header.html" . }}.

This happened in v0.42:

We have now virtualized the filesystems for project and theme files. This makes everything simpler, faster and more powerful. But it also means that template lookups on the form {{ template “theme/partials/pagination.html” . }} will not work anymore. That syntax has never been documented, so it’s not expected to be in wide use.

change 2: .Data.Pages is now site.RegularPages

This seems to be discussed in the release notes for 0.57.2

I just needed to replace .Data.Pages with site.RegularPages in the template on the homepage as well as in my RSS feed template.

change 3: .Next and .Prev got flipped

I had this comment in the part of my theme where I link to the next/previous blog post:

“next” and “previous” in hugo apparently mean the opposite of what I’d think they’d mean intuitively. I’d expect “next” to mean “in the future” and “previous” to mean “in the past” but it’s the opposite

It looks they changed this in ad705aac064 so that “next” actually is in the future and “prev” actually is in the past. I definitely find the new behaviour more intuitive.

downloading the Hugo changelogs with a script

Figuring out why/when all of these changes happened was a little difficult. I ended up hacking together a bash script to download all of the changelogs from github as text files, which I could then grep to try to figure out what happened. It turns out it’s pretty easy to get all of the changelogs from the GitHub API.

So far everything was not so bad – there was also a change around taxonomies that’s I can’t quite explain, but it was all pretty manageable, but then we got to the really tough one: the markdown renderer.

change 4: the markdown renderer (blackfriday -> goldmark)

The blackfriday markdown renderer (which was previously the default) was removed in v0.100.0. This seems pretty reasonable:

It has been deprecated for a long time, its v1 version is not maintained anymore, and there are many known issues. Goldmark should be a mature replacement by now.

Fixing all my Markdown changes was a huge pain – I ended up having to update 80 different Markdown files (out of 700) so that they would render properly, and I’m not totally sure

why bother switching renderers?

The obvious question here is – why bother even trying to upgrade Hugo at all if I have to switch Markdown renderers? My old site was running totally fine and I think it wasn’t necessarily a good use of time, but the one reason I think it might be useful in the future is that the new renderer (goldmark) uses the CommonMark markdown standard, which I’m hoping will be somewhat more futureproof. So maybe I won’t have to go through this again? We’ll see.

Also it turned out that the new Goldmark renderer does fix some problems I had (but didn’t know that I had) with smart quotes and how lists/blockquotes interact.

finding all the Markdown problems: the process

The hard part of this Markdown change was even figuring out what changed. Almost all of the problems (including #2 and #3 above) just silently broke the site, they didn’t cause any errors or anything. So I had to diff the HTML to hunt them down.

Here’s what I ended up doing:

- Generate the site with the old version, put it in

public_old - Generate the new version, put it in

public - Diff every single HTML file in

public/andpublic_oldwith this diff.sh script and put the results in adiffs/folder - Run variations on

find diffs -type f | xargs cat | grep -C 5 '(31m|32m)' | less -rover and over again to look at every single change until I found something that seemed wrong - Update the Markdown to fix the problem

- Repeat until everything seemed okay

(the grep 31m|32m thing is searching for red/green text in the diff)

This was very time consuming but it was a little bit fun for some reason so I kept doing it until it seemed like nothing too horrible was left.

the new markdown rules

Here’s a list of every type of Markdown change I had to make. It’s very possible these are all extremely specific to me but it took me a long time to figure them all out so maybe this will be helpful to one other person who finds this in the future.

4.1: mixing HTML and markdown

This doesn’t work anymore (it doesn’t expand the link):

<small>

[a link](https://example.com)

</small>

I need to do this instead:

<small>

[a link](https://example.com)

</small>

This works too:

<small> [a link](https://example.com) </small>

4.2: << is changed into «

I didn’t want this so I needed to configure:

markup:

goldmark:

extensions:

typographer:

leftAngleQuote: '<<'

rightAngleQuote: '>>'

4.3: nested lists sometimes need 4 space indents

This doesn’t render as a nested list anymore if I only indent by 2 spaces, I need to put 4 spaces.

1. a

* b

* c

2. b

The problem is that the amount of indent needed depends on the size of the list markers. Here’s a reference in CommonMark for this.

4.4: blockquotes inside lists work better

Previously the > quote here didn’t render as a blockquote, and with the new renderer it does.

* something

> quote

* something else

I found a bunch of Markdown that had been kind of broken (which I hadn’t noticed) that works better with the new renderer, and this is an example of that.

Lists inside blockquotes also seem to work better.

4.5: headings inside lists

Previously this didn’t render as a heading, but now it does. So I needed to

replace the # with #.

* # passengers: 20

4.6: + or 1) at the beginning of the line makes it a list

I had something which looked like this:

`1 / (1

+ exp(-1)) = 0.73`

With Blackfriday it rendered like this:

<p><code>1 / (1

+ exp(-1)) = 0.73</code></p>

and with Goldmark it rendered like this:

<p>`1 / (1</p>

<ul>

<li>exp(-1)) = 0.73`</li>

</ul>

Same thing if there was an accidental 1) at the beginning of a line, like in this Markdown snippet

I set up a small Hadoop cluster (1 master, 2 workers, replication set to

1) on

To fix this I just had to rewrap the line so that the + wasn’t the first character.

The Markdown is formatted this way because I wrap my Markdown to 80 characters a lot and the wrapping isn’t very context sensitive.

4.7: no more smart quotes in code blocks

There were a bunch of places where the old renderer (Blackfriday) was doing

unwanted things in code blocks like replacing ... with … or replacing

quotes with smart quotes. I hadn’t realized this was happening and I was very

happy to have it fixed.

4.8: better quote management

The way this gets rendered got better:

"Oh, *interesting*!"

- old: “Oh, interesting!“

- new: “Oh, interesting!”

Before there were two left smart quotes, now the quotes match.

4.9: images are no longer wrapped in a p tag

Previously if I had an image like this:

<img src="https://jvns.ca/images/rustboot1.png">

it would get wrapped in a <p> tag, now it doesn’t anymore. I dealt with this

just by adding a margin-bottom: 0.75em to images in the CSS, hopefully

that’ll make them display well enough.

4.10: <br> is now wrapped in a p tag

Previously this wouldn’t get wrapped in a p tag, but now it seems to:

<br><br>

I just gave up on fixing this though and resigned myself to maybe having some extra space in some cases. Maybe I’ll try to fix it later if I feel like another yakshave.

4.11: some more goldmark settings

I also needed to

- turn off code highlighting (because it wasn’t working properly and I didn’t have it before anyway)

- use the old “blackfriday” method to generate heading IDs so they didn’t change

- allow raw HTML in my markdown

Here’s what I needed to add to my config.yaml to do all that:

markup:

highlight:

codeFences: false

goldmark:

renderer:

unsafe: true

parser:

autoHeadingIDType: blackfriday

Maybe I’ll try to get syntax highlighting working one day, who knows. I might prefer having it off though.

a little script to compare blackfriday and goldmark

I also wrote a little program to compare the Blackfriday and Goldmark output for various markdown snippets, here it is in a gist.

It’s not really configured the exact same way Blackfriday and Goldmark were in my Hugo versions, but it was still helpful to have to help me understand what was going on.

a quick note on maintaining themes

My approach to themes in Hugo has been:

- pay someone to make a nice design for the site (for example wizardzines.com was designed by Melody Starling)

- use a totally custom theme

- commit that theme to the same Github repo as the site

So I just need to edit the theme files to fix any problems. Also I wrote a lot of the theme myself so I’m pretty familiar with how it works.

Relying on someone else to keep a theme updated feels kind of scary to me, I think if I were using a third-party theme I’d just copy the code into my site’s github repo and then maintain it myself.

which static site generators have better backwards compatibility?

I asked on Mastodon if anyone had used a static site generator with good backwards compatibility.

The main answers seemed to be Jekyll and 11ty. Several people said they’d been using Jekyll for 10 years without any issues, and 11ty says it has stability as a core goal.

I think a big factor in how appealing Jekyll/11ty are is how easy it is for you to maintain a working Ruby / Node environment on your computer: part of the reason I stopped using Jekyll was that I got tired of having to maintain a working Ruby installation. But I imagine this wouldn’t be a problem for a Ruby or Node developer.

Several people said that they don’t build their Jekyll site locally at all – they just use GitHub Pages to build it.

that’s it!

Overall I’ve been happy with Hugo – I started using it because it had fast build times and it was a static binary, and both of those things are still extremely useful to me. I might have spent 10 hours on this upgrade, but I’ve probably spent 1000+ hours writing blog posts without thinking about Hugo at all so that seems like an extremely reasonable ratio.

I find it hard to be too mad about the backwards incompatible changes, most of

them were quite a long time ago, Hugo does a great job of making their old

releases available so you can use the old release if you want, and the most

difficult one is removing support for the blackfriday Markdown renderer in

favour of using something CommonMark-compliant which seems pretty reasonable to

me even if it is a huge pain.

But it did take a long time and I don’t think I’d particularly recommend moving 700 blog posts to a new Markdown renderer unless you’re really in the mood for a lot of computer suffering for some reason.

The new renderer did fix a bunch of problems so I think overall it might be a good thing, even if I’ll have to remember to make 2 changes to how I write Markdown (4.1 and 4.3).

Also I’m still using Hugo 0.54 for https://wizardzines.com so maybe these notes will be useful to Future Me if I ever feel like upgrading Hugo for that site.

Hopefully I didn’t break too many things on the blog by doing this, let me know if you see anything broken!

Terminal colours are tricky

Yesterday I was thinking about how long it took me to get a colorscheme in my terminal that I was mostly happy with (SO MANY YEARS), and it made me wonder what about terminal colours made it so hard.

So I asked people on Mastodon what problems they’ve run into with colours in the terminal, and I got a ton of interesting responses! Let’s talk about some of the problems and a few possible ways to fix them.

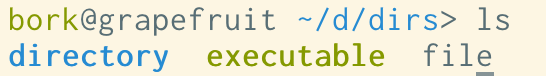

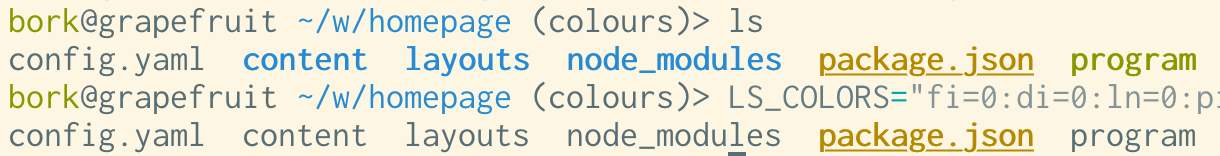

problem 1: blue on black

One of the top complaints was “blue on black is hard to read”. Here’s an

example of that: if I open Terminal.app, set the background to black, and run

ls, the directories are displayed in a blue that isn’t that easy to read:

To understand why we’re seeing this blue, let’s talk about ANSI colours!

the 16 ANSI colours

Your terminal has 16 numbered colours – black, red, green, yellow, blue, magenta, cyan, white, and “bright” version of each of those.

Programs can use them by printing out an “ANSI escape code” – for example if you want to see each of the 16 colours in your terminal, you can run this Python program:

def color(num, text):

return f"\033[38;5;{num}m{text}\033[0m"

for i in range(16):

print(color(i, f"number {i:02}"))

what are the ANSI colours?

This made me wonder – if blue is colour number 5, who decides what hex color that should correspond to?

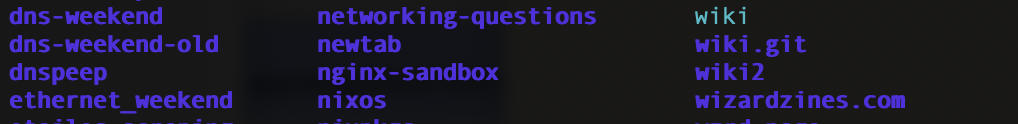

The answer seems to be “there’s no standard, terminal emulators just choose colours and it’s not very consistent”. Here’s a screenshot of a table from Wikipedia, where you can see that there’s a lot of variation:

problem 1.5: bright yellow on white

Bright yellow on white is even worse than blue on black, here’s what I get in a terminal with the default settings:

That’s almost impossible to read (and some other colours like light green cause similar issues), so let’s talk about solutions!

two ways to reconfigure your colours

If you’re annoyed by these colour contrast issues (or maybe you just think the default ANSI colours are ugly), you might think – well, I’ll just choose a different “blue” and pick something I like better!

There are two ways you can do this:

Way 1: Configure your terminal emulator: I think most modern terminal emulators have a way to reconfigure the colours, and some of them even come with some preinstalled themes that you might like better than the defaults.

Way 2: Run a shell script: There are ANSI escape codes that you can print

out to tell your terminal emulator to reconfigure its colours. Here’s a shell script that does that,

from the base16-shell project.

You can see that it has a few different conventions for changing the colours –

I guess different terminal emulators have different escape codes for changing

their colour palette, and so the script is trying to pick the right style of

escape code based on the TERM environment variable.

what are the pros and cons of the 2 ways of configuring your colours?

I prefer to use the “shell script” method, because:

- if I switch terminal emulators for some reason, I don’t need to a different configuration system, my colours still Just Work

- I use base16-shell with base16-vim to make my vim colours match my terminal colours, which is convenient

some advantages of configuring colours in your terminal emulator:

- if you use a popular terminal emulator, there are probably a lot more nice terminal themes out there that you can choose from

- not all terminal emulators support the “shell script method”, and even if they do, the results can be a little inconsistent

This is what my shell has looked like for probably the last 5 years (using the

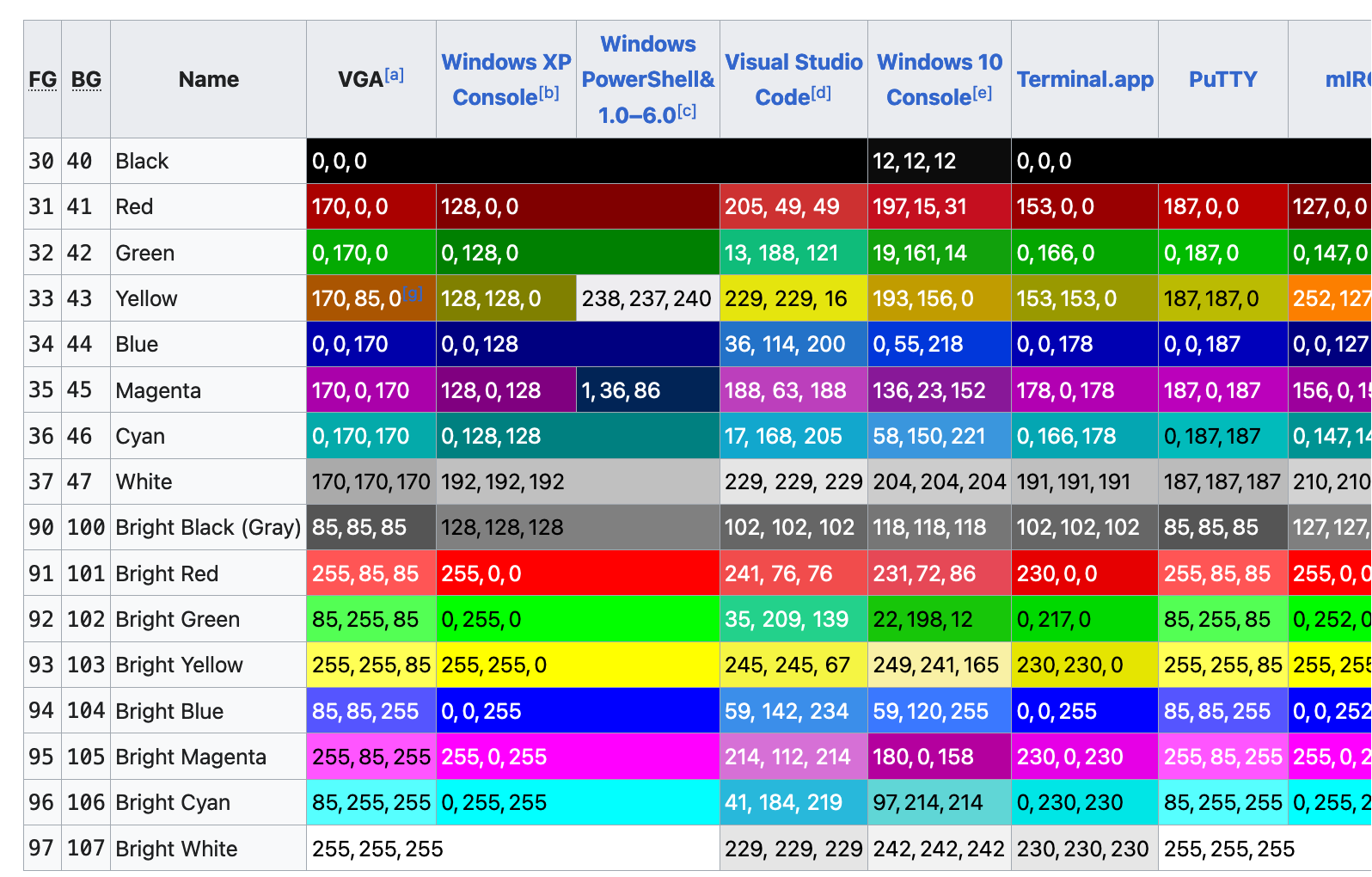

solarized light base16 theme), and I’m pretty happy with it. Here’s htop:

Okay, so let’s say you’ve found a terminal colorscheme that you like. What else can go wrong?

problem 2: programs using 256 colours

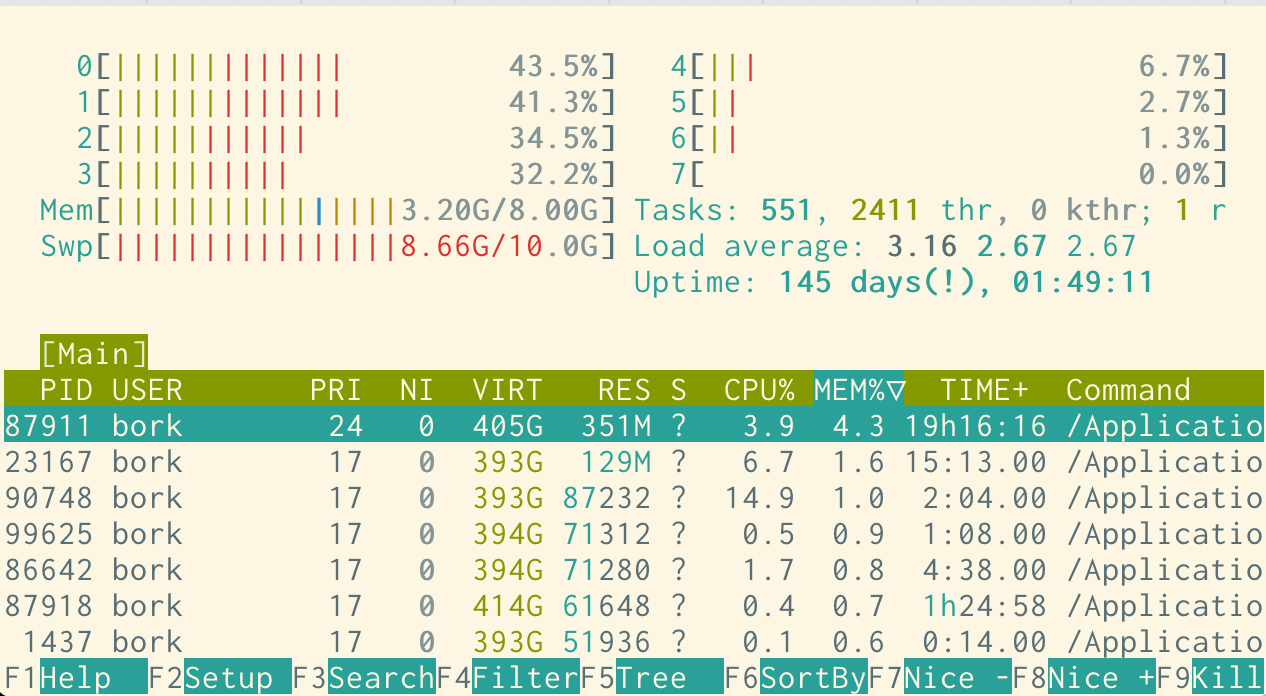

Here’s what some output of fd, a find alternative, looks like in my

colorscheme:

The contrast is pretty bad here, and I definitely don’t have that lime green in my normal colorscheme. What’s going on?

We can see what color codes fd is using using the unbuffer program to

capture its output including the color codes:

$ unbuffer fd . > out

$ vim out

^[[38;5;48mbad-again.sh^[[0m

^[[38;5;48mbad.sh^[[0m

^[[38;5;48mbetter.sh^[[0m

out

^[[38;5;48 means “set the foreground color to color 48”. Terminals don’t

only have 16 colours – many terminals these days actually have 3 ways of

specifying colours:

- the 16 ANSI colours we already talked about

- an extended set of 256 colours

- a further extended set of 24-bit hex colours, like

#ffea03

So fd is using one of the colours from the extended 256-color set. bat (a

cat alternative) does something similar – here’s what it looks like by

default in my terminal.

This looks fine though and it really seems like it’s trying to work well with a variety of terminal themes.

some newer tools seem to have theme support

I think it’s interesting that some of these newer terminal tools (fd, cat,

delta, and probably more) have support for arbitrary custom themes. I guess

the downside of this approach is that the default theme might clash with your

terminal’s background, but the upside is that it gives you a lot more control

over theming the tool’s output than just choosing 16 ANSI colours.

I don’t really use bat, but if I did I’d probably use bat --theme ansi to

just use the ANSI colours that I have set in my normal terminal colorscheme.

problem 3: the grays in Solarized

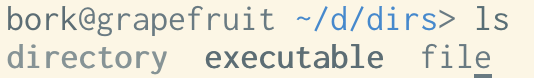

A bunch of people on Mastodon mentioned a specific issue with grays in the Solarized theme: when I list a directory, the base16 Solarized Light theme looks like this:

but iTerm’s default Solarized Light theme looks like this:

This is because in the iTerm theme (which is the original Solarized design), colors 9-14 (the “bright blue”, “bright

red”, etc) are mapped to a series of grays, and when I run ls, it’s trying to

use those “bright” colours to color my directories and executables.

My best guess for why the original Solarized theme is designed this way is to make the grays available to the vim Solarized colorscheme.

I’m pretty sure I prefer the modified base16 version I use where the “bright” colours are actually colours instead of all being shades of gray though. (I didn’t actually realize the version I was using wasn’t the “original” Solarized theme until I wrote this post)

In any case I really love Solarized and I’m very happy it exists so that I can use a modified version of it.

problem 4: a vim theme that doesn’t match the terminal background

If I my vim theme has a different background colour than my terminal theme, I get this ugly border, like this:

This one is a pretty minor issue though and I think making your terminal background match your vim background is pretty straightforward.

problem 5: programs setting a background color

A few people mentioned problems with terminal applications setting an unwanted background colour, so let’s look at an example of that.

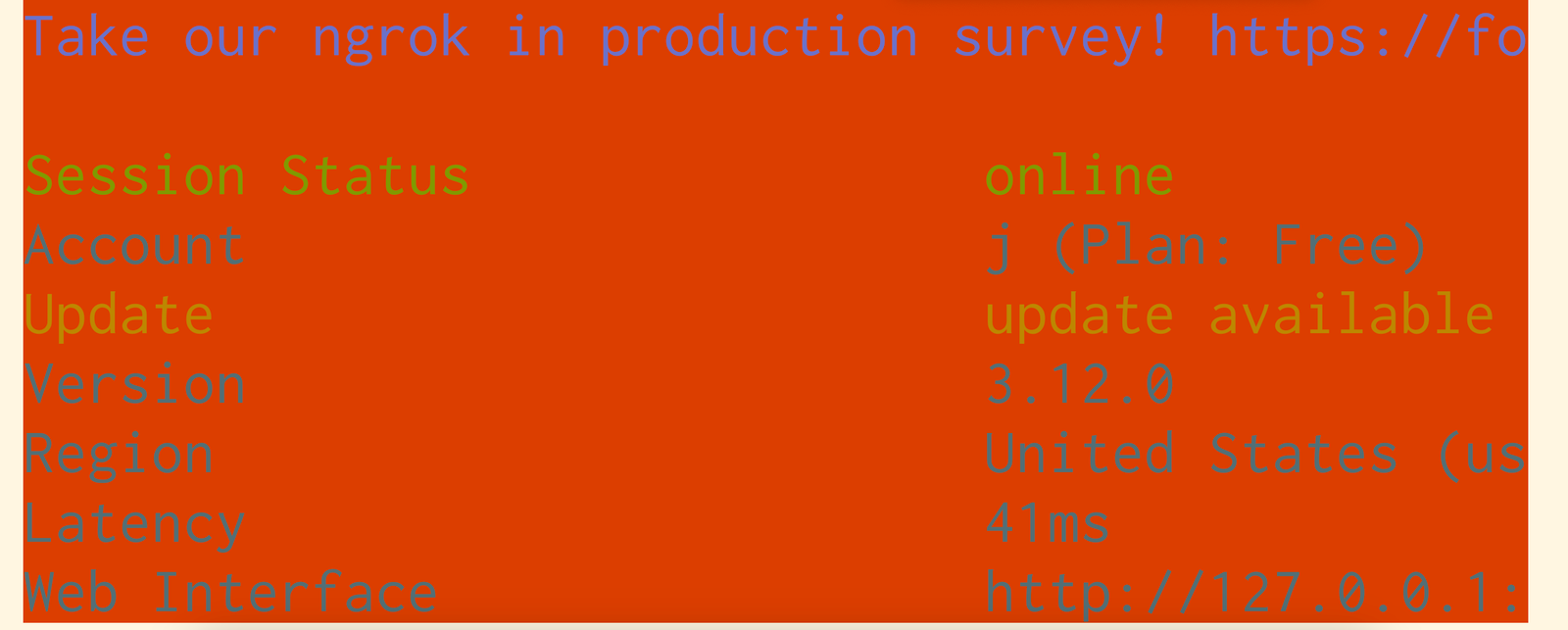

Here ngrok has set the background to color #16 (“black”), but the

base16-shell script I use sets color 16 to be bright orange, so I get this,

which is pretty bad:

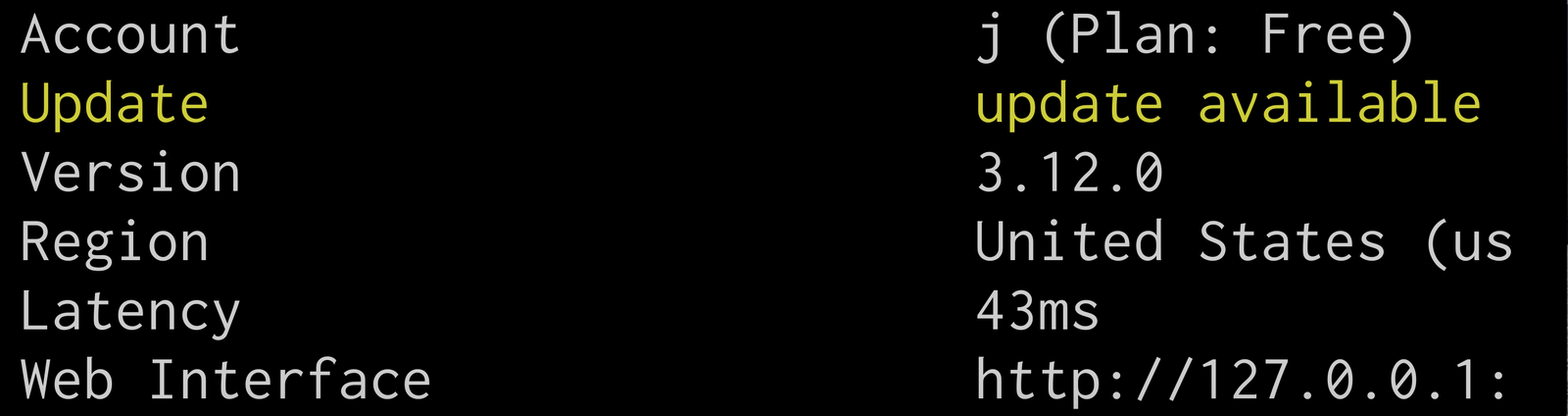

I think the intention is for ngrok to look something like this:

I think base16-shell sets color #16 to orange (instead of black)

so that it can provide extra colours for use by base16-vim.

This feels reasonable to me – I use base16-vim in the terminal, so I guess I’m

using that feature and it’s probably more important to me than ngrok (which I

rarely use) behaving a bit weirdly.

This particular issue is a maybe obscure clash between ngrok and my colorschem, but I think this kind of clash is pretty common when a program sets an ANSI background color that the user has remapped for some reason.

a nice solution to contrast issues: “minimum contrast”

A bunch of terminals (iTerm2, tabby, kitty’s text_fg_override_threshold, and folks tell me also Ghostty and Windows Terminal) have a “minimum contrast” feature that will automatically adjust colours to make sure they have enough contrast.

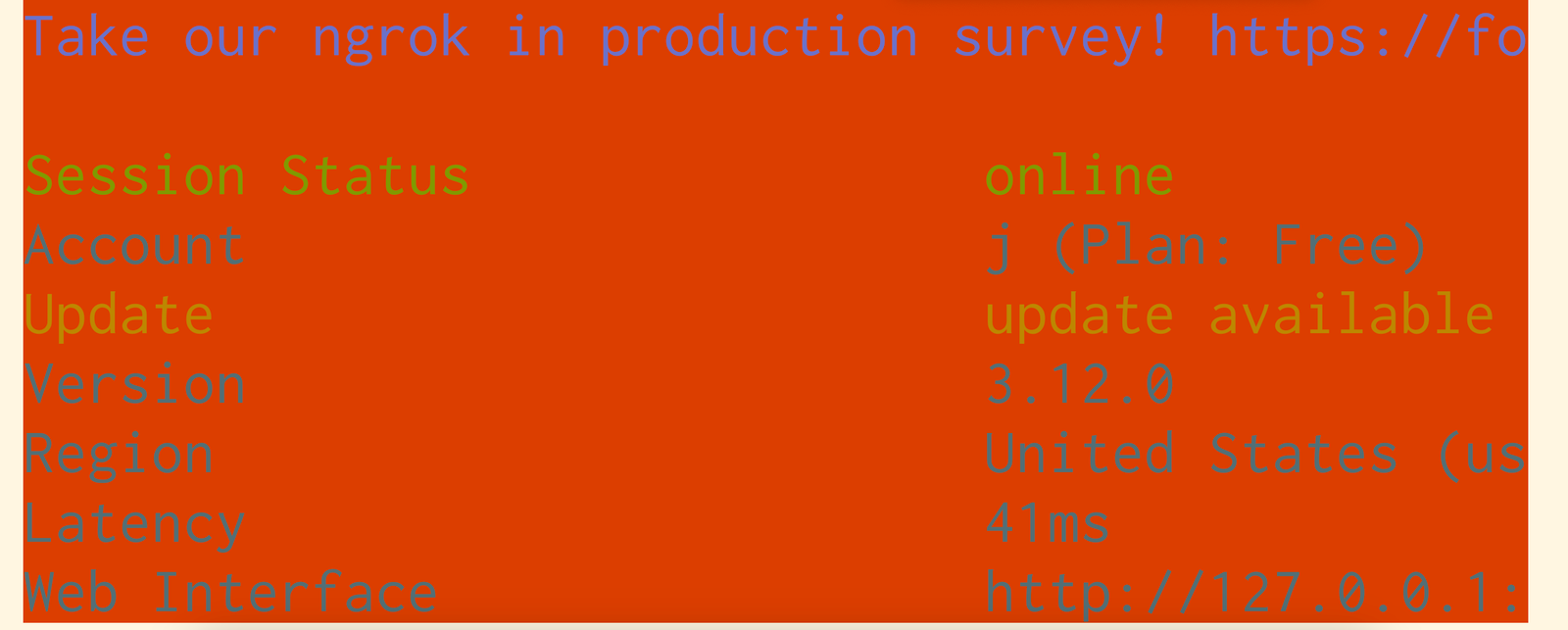

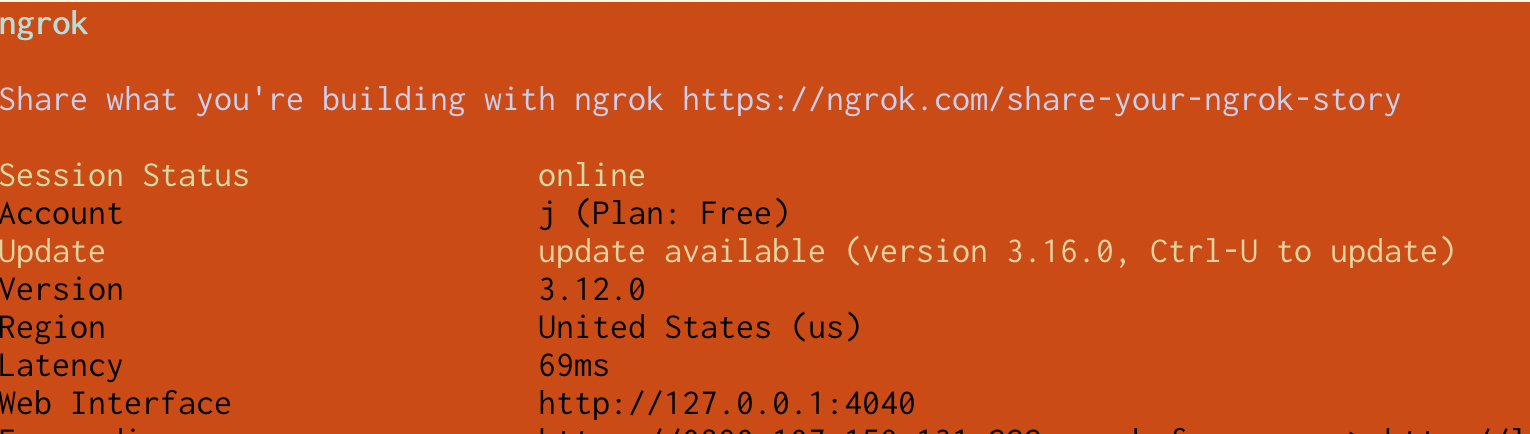

Here’s an example from iTerm. This ngrok accident from before has pretty bad contrast, I find it pretty difficult to read:

With “minimum contrast” set to 40 in iTerm, it looks like this instead:

I didn’t have minimum contrast turned on before but I just turned it on today because it makes such a big difference when something goes wrong with colours in the terminal.

problem 6: TERM being set to the wrong thing

A few people mentioned that they’ll SSH into a system that doesn’t support the

TERM environment variable that they have set locally, and then the colours

won’t work.

I think the way TERM works is that systems have a terminfo database, so if

the value of the TERM environment variable isn’t in the system’s terminfo

database, then it won’t know how to output colours for that terminal. I don’t

know too much about terminfo, but someone linked me to this terminfo rant that talks about a few other

issues with terminfo.

I don’t have a system on hand to reproduce this one so I can’t say for sure how

to fix it, but this stackoverflow question

suggests running something like TERM=xterm ssh instead of ssh.

problem 7: picking “good” colours is hard

A couple of problems people mentioned with designing / finding terminal colorschemes:

- some folks are colorblind and have trouble finding an appropriate colorscheme

- accidentally making the background color too close to the cursor or selection color, so they’re hard to find

- generally finding colours that work with every program is a struggle (for example you can see me having a problem with this with ngrok above!)

problem 8: making nethack/mc look right

Another problem people mentioned is using a program like nethack or midnight commander which you might expect to have a specific colourscheme based on the default ANSI terminal colours.

For example, midnight commander has a really specific classic look:

But in my Solarized theme, midnight commander looks like this:

The Solarized version feels like it could be disorienting if you’re very used to the “classic” look.

One solution Simon Tatham mentioned to this is using some palette customization ANSI codes (like the ones base16 uses that I talked about earlier) to change the color palette right before starting the program, for example remapping yellow to a brighter yellow before starting Nethack so that the yellow characters look better.

problem 9: commands disabling colours when writing to a pipe

If I run fd | less, I see something like this, with the colours disabled.

In general I find this useful – if I pipe a command to grep, I don’t want it

to print out all those color escape codes, I just want the plain text. But what if you want to see the colours?

To see the colours, you can run unbuffer fd | less -r! I just learned about

unbuffer recently and I think it’s really cool, unbuffer opens a tty for the

command to write to so that it thinks it’s writing to a TTY. It also fixes

issues with programs buffering their output when writing to a pipe, which is

why it’s called unbuffer.

Here’s what the output of unbuffer fd | less -r looks like for me:

Also some commands (including fd) support a --color=always flag which will

force them to always print out the colours.

problem 10: unwanted colour in ls and other commands

Some people mentioned that they don’t want ls to use colour at all, perhaps

because ls uses blue, it’s hard to read on black, and maybe they don’t feel like

customizing their terminal’s colourscheme to make the blue more readable or

just don’t find the use of colour helpful.

Some possible solutions to this one:

- you can run

ls --color=never, which is probably easiest - you can also set

LS_COLORSto customize the colours used byls. I think some other programs other thanlssupport theLS_COLORSenvironment variable too. - also some programs support setting

NO_COLOR=true(there’s a list here)

Here’s an example of running LS_COLORS="fi=0:di=0:ln=0:pi=0:so=0:bd=0:cd=0:or=0:ex=0" ls:

problem 11: the colours in vim

I used to have a lot of problems with configuring my colours in vim – I’d set up my terminal colours in a way that I thought was okay, and then I’d start vim and it would just be a disaster.

I think what was going on here is that today, there are two ways to set up a vim colorscheme in the terminal:

- using your ANSI terminal colours – you tell vim which ANSI colour number to use for the background, for functions, etc.

- using 24-bit hex colours – instead of ANSI terminal colours, the vim colorscheme can use hex codes like #faea99 directly

20 years ago when I started using vim, terminals with 24-bit hex color support were a lot less common (or maybe they didn’t exist at all), and vim certainly didn’t have support for using 24-bit colour in the terminal. From some quick searching through git, it looks like vim added support for 24-bit colour in 2016 – just 8 years ago!

So to get colours to work properly in vim before 2016, you needed to synchronize

your terminal colorscheme and your vim colorscheme. Here’s what that looked like,

the colorscheme needed to map the vim color classes like cterm05 to ANSI colour numbers.

But in 2024, the story is really different! Vim (and Neovim, which I use now)

support 24-bit colours, and as of Neovim 0.10 (released in May 2024), the

termguicolors setting (which tells Vim to use 24-bit hex colours for

colorschemes) is turned on by default in any terminal with 24-bit

color support.

So this “you need to synchronize your terminal colorscheme and your vim colorscheme” problem is not an issue anymore for me in 2024, since I don’t plan to use terminals without 24-bit color support in the future.

The biggest consequence for me of this whole thing is that I don’t need base16

to set colors 16-21 to weird stuff anymore to integrate with vim – I can just

use a terminal theme and a vim theme, and as long as the two themes use similar

colours (so it’s not jarring for me to switch between them) there’s no problem.

I think I can just remove those parts from my base16 shell script and totally

avoid the problem with ngrok and the weird orange background I talked about

above.

some more problems I left out

I think there are a lot of issues around the intersection of multiple programs, like using some combination tmux/ssh/vim that I couldn’t figure out how to reproduce well enough to talk about them. Also I’m sure I missed a lot of other things too.

base16 has really worked for me

I’ve personally had a lot of success with using

base16-shell with

base16-vim – I just need to add a couple of lines to my

fish config to set it up (+ a few .vimrc lines) and then I can move on and

accept any remaining problems that that doesn’t solve.

I don’t think base16 is for everyone though, some limitations I’m aware of with base16 that might make it not work for you:

- it comes with a limited set of builtin themes and you might not like any of them

- the Solarized base16 theme (and maybe all of the themes?) sets the “bright” ANSI colours to be exactly the same as the normal colours, which might cause a problem if you’re relying on the “bright” colours to be different from the regular ones

- it sets colours 16-21 in order to give the vim colorschemes from

base16-vimaccess to more colours, which might not be relevant if you always use a terminal with 24-bit color support, and can cause problems like the ngrok issue above - also the way it sets colours 16-21 could be a problem in terminals that don’t have 256-color support, like the linux framebuffer terminal

Apparently there’s a community fork of base16 called tinted-theming, which I haven’t looked into much yet.

some other colorscheme tools

Just one so far but I’ll link more if people tell me about them:

- rootloops.sh for generating colorschemes (and “let’s create a terminal color scheme”)

- Some popular colorschemes (according to people I asked on Mastodon): catpuccin, Monokai, Gruvbox, Dracula, Modus (a high contrast theme), Tokyo Night, Nord, Rosé Pine

okay, that was a lot

We talked about a lot in this post and while I think learning about all these details is kind of fun if I’m in the mood to do a deep dive, I find it SO FRUSTRATING to deal with it when I just want my colours to work! Being surprised by unreadable text and having to find a workaround is just not my idea of a good day.

Personally I’m a zero-configuration kind of person and it’s not that appealing to me to have to put together a lot of custom configuration just to make my colours in the terminal look acceptable. I’d much rather just have some reasonable defaults that I don’t have to change.

minimum contrast seems like an amazing feature

My one big takeaway from writing this was to turn on “minimum contrast” in my terminal, I think it’s going to fix most of the occasional accidental unreadable text issues I run into and I’m pretty excited about it.

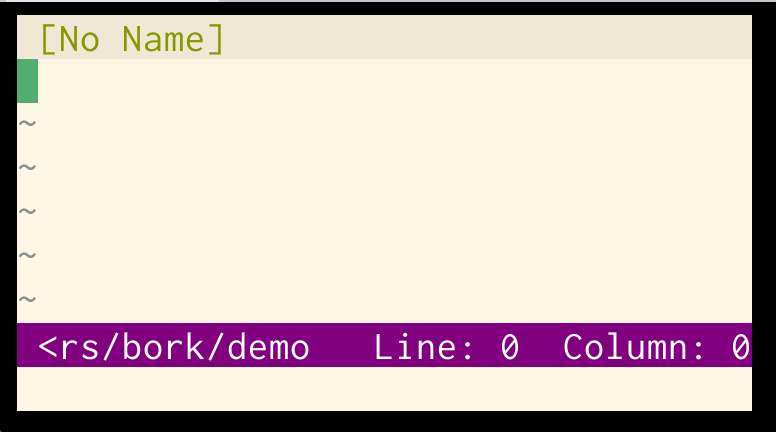

Some Go web dev notes

I spent a lot of time in the past couple of weeks working on a website in Go that may or may not ever see the light of day, but I learned a couple of things along the way I wanted to write down. Here they are:

go 1.22 now has better routing

I’ve never felt motivated to learn any of the Go routing libraries (gorilla/mux, chi, etc), so I’ve been doing all my routing by hand, like this.

// DELETE /records:

case r.Method == "DELETE" && n == 1 && p[0] == "records":

if !requireLogin(username, r.URL.Path, r, w) {

return

}

deleteAllRecords(ctx, username, rs, w, r)

// POST /records/<ID>

case r.Method == "POST" && n == 2 && p[0] == "records" && len(p[1]) > 0:

if !requireLogin(username, r.URL.Path, r, w) {

return

}

updateRecord(ctx, username, p[1], rs, w, r)

But apparently as of Go 1.22, Go now has better support for routing in the standard library, so that code can be rewritten something like this:

mux.HandleFunc("DELETE /records/", app.deleteAllRecords)

mux.HandleFunc("POST /records/{record_id}", app.updateRecord)

Though it would also need a login middleware, so maybe something more like

this, with a requireLogin middleware.

mux.Handle("DELETE /records/", requireLogin(http.HandlerFunc(app.deleteAllRecords)))

a gotcha with the built-in router: redirects with trailing slashes

One annoying gotcha I ran into was: if I make a route for /records/, then a

request for /records will be redirected to /records/.

I ran into an issue with this where sending a POST request to /records

redirected to a GET request for /records/, which broke the POST request

because it removed the request body. Thankfully Xe Iaso wrote a blog post about the exact same issue which made it

easier to debug.

I think the solution to this is just to use API endpoints like POST /records

instead of POST /records/, which seems like a more normal design anyway.

sqlc automatically generates code for my db queries

I got a little bit tired of writing so much boilerplate for my SQL queries, but I didn’t really feel like learning an ORM, because I know what SQL queries I want to write, and I didn’t feel like learning the ORM’s conventions for translating things into SQL queries.

But then I found sqlc, which will compile a query like this:

-- name: GetVariant :one

SELECT *

FROM variants

WHERE id = ?;

into Go code like this:

const getVariant = `-- name: GetVariant :one

SELECT id, created_at, updated_at, disabled, product_name, variant_name

FROM variants

WHERE id = ?

`

func (q *Queries) GetVariant(ctx context.Context, id int64) (Variant, error) {

row := q.db.QueryRowContext(ctx, getVariant, id)

var i Variant

err := row.Scan(

&i.ID,

&i.CreatedAt,

&i.UpdatedAt,

&i.Disabled,

&i.ProductName,

&i.VariantName,

)

return i, err

}

What I like about this is that if I’m ever unsure about what Go code to write for a given SQL query, I can just write the query I want, read the generated function and it’ll tell me exactly what to do to call it. It feels much easier to me than trying to dig through the ORM’s documentation to figure out how to construct the SQL query I want.

Reading Brandur’s sqlc notes from 2024 also gave me some confidence that this is a workable path for my tiny programs. That post gives a really helpful example of how to conditionally update fields in a table using CASE statements (for example if you have a table with 20 columns and you only want to update 3 of them).

sqlite tips

Someone on Mastodon linked me to this post called Optimizing sqlite for servers. My projects are small and I’m not so concerned about performance, but my main takeaways were:

- have a dedicated object for writing to the database, and run

db.SetMaxOpenConns(1)on it. I learned the hard way that if I don’t do this then I’ll getSQLITE_BUSYerrors from two threads trying to write to the db at the same time. - if I want to make reads faster, I could have 2 separate db objects, one for writing and one for reading

There are a more tips in that post that seem useful (like “COUNT queries are slow” and “Use STRICT tables”), but I haven’t done those yet.

Also sometimes if I have two tables where I know I’ll never need to do a JOIN

beteween them, I’ll just put them in separate databases so that I can connect

to them independently.

Go 1.19 introduced a way to set a GC memory limit

I run all of my Go projects in VMs with relatively little memory, like 256MB or 512MB. I ran into an issue where my application kept getting OOM killed and it was confusing – did I have a memory leak? What?

After some Googling, I realized that maybe I didn’t have a memory leak, maybe I just needed to reconfigure the garbage collector! It turns out that by default (according to A Guide to the Go Garbage Collector), Go’s garbage collector will let the application allocate memory up to 2x the current heap size.

Mess With DNS’s base heap size is around 170MB and the amount of memory free on the VM is around 160MB right now, so if its memory doubled, it’ll get OOM killed.

In Go 1.19, they added a way to tell Go “hey, if the application starts using this much memory, run a GC”. So I set the GC memory limit to 250MB and it seems to have resulted in the application getting OOM killed less often:

export GOMEMLIMIT=250MiB

some reasons I like making websites in Go

I’ve been making tiny websites (like the nginx playground) in Go on and off for the last 4 years or so and it’s really been working for me. I think I like it because:

- there’s just 1 static binary, all I need to do to deploy it is copy the binary. If there are static files I can just embed them in the binary with embed.

- there’s a built-in webserver that’s okay to use in production, so I don’t need to configure WSGI or whatever to get it to work. I can just put it behind Caddy or run it on fly.io or whatever.

- Go’s toolchain is very easy to install, I can just do

apt-get install golang-goor whatever and then ago buildwill build my project - it feels like there’s very little to remember to start sending HTTP responses

– basically all there is are functions like

Serve(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request)which read the request and send a response. If I need to remember some detail of how exactly that’s accomplished, I just have to read the function! - also

net/httpis in the standard library, so you can start making websites without installing any libraries at all. I really appreciate this one. - Go is a pretty systems-y language, so if I need to run an

ioctlor something that’s easy to do

In general everything about it feels like it makes projects easy to work on for 5 days, abandon for 2 years, and then get back into writing code without a lot of problems.

For contrast, I’ve tried to learn Rails a couple of times and I really want to love Rails – I’ve made a couple of toy websites in Rails and it’s always felt like a really magical experience. But ultimately when I come back to those projects I can’t remember how anything works and I just end up giving up. It feels easier to me to come back to my Go projects that are full of a lot of repetitive boilerplate, because at least I can read the code and figure out how it works.

things I haven’t figured out yet

some things I haven’t done much of yet in Go:

- rendering HTML templates: usually my Go servers are just APIs and I make the

frontend a single-page app with Vue. I’ve used

html/templatea lot in Hugo (which I’ve used for this blog for the last 8 years) but I’m still not sure how I feel about it. - I’ve never made a real login system, usually my servers don’t have users at all.

- I’ve never tried to implement CSRF

In general I’m not sure how to implement security-sensitive features so I don’t start projects which need login/CSRF/etc. I imagine this is where a framework would help.

it’s cool to see the new features Go has been adding

Both of the Go features I mentioned in this post (GOMEMLIMIT and the routing)

are new in the last couple of years and I didn’t notice when they came out. It

makes me think I should pay closer attention to the release notes for new Go

versions.

Reasons I still love the fish shell

I wrote about how much I love fish in this blog post from 2017 and, 7 years of using it every day later, I’ve found even more reasons to love it. So I thought I’d write a new post with both the old reasons I loved it and some reasons.

This came up today because I was trying to figure out why my terminal doesn’t break anymore when I cat a binary to my terminal, the answer was “fish fixes the terminal!”, and I just thought that was really nice.

1. no configuration

In 10 years of using fish I have never found a single thing I wanted to configure. It just works the way I want. My fish config file just has:

- environment variables

- aliases (

alias ls eza,alias vim nvim, etc) - the occasional

direnv hook fish | sourceto integrate a tool like direnv - a script I run to set up my terminal colours

I’ve been told that configuring things in fish is really easy if you ever do want to configure something though.

2. autosuggestions from my shell history

My absolute favourite thing about fish is that I type, it’ll automatically suggest (in light grey) a matching command that I ran recently. I can press the right arrow key to accept the completion, or keep typing to ignore it.

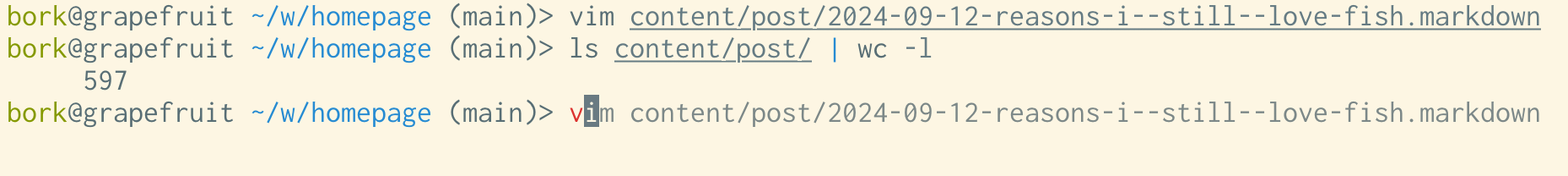

Here’s what that looks like. In this example I just typed the “v” key and it guessed that I want to run the previous vim command again.

2.5 “smart” shell autosuggestions

One of my favourite subtle autocomplete features is how fish handles autocompleting commands that contain paths in them. For example, if I run:

$ ls blah.txt

that command will only be autocompleted in directories that contain blah.txt – it won’t show up in a different directory. (here’s a short comment about how it works)

As an example, if in this directory I type bash scripts/, it’ll only suggest

history commands including files that actually exist in my blog’s scripts

folder, and not the dozens of other irrelevant scripts/ commands I’ve run in

other folders.

I didn’t understand exactly how this worked until last week, it just felt like fish was magically able to suggest the right commands. It still feels a little like magic and I love it.

3. pasting multiline commands

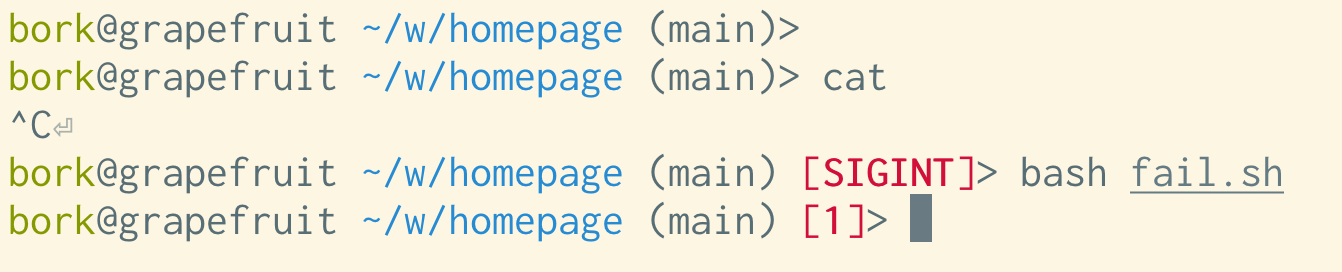

If I copy and paste multiple lines, bash will run them all, like this:

[bork@grapefruit linux-playground (main)]$ echo hi

hi

[bork@grapefruit linux-playground (main)]$ touch blah

[bork@grapefruit linux-playground (main)]$ echo hi

hi

This is a bit alarming – what if I didn’t actually want to run all those commands?

Fish will paste them all at a single prompt, so that I can press Enter if I actually want to run them. Much less scary.

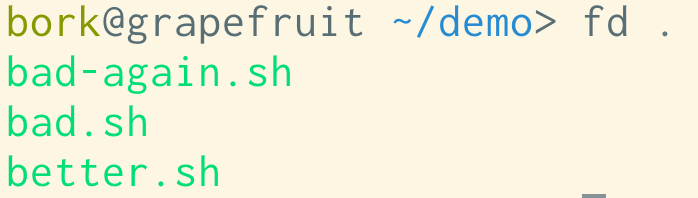

bork@grapefruit ~/work/> echo hi

touch blah

echo hi

4. nice tab completion

If I run ls and press tab, it’ll display all the filenames in a nice grid. I can use either Tab, Shift+Tab, or the arrow keys to navigate the grid.

Also, I can tab complete from the middle of a filename – if the filename starts with a weird character (or if it’s just not very unique), I can type some characters from the middle and press tab.

Here’s what the tab completion looks like:

bork@grapefruit ~/work/> ls

api/ blah.py fly.toml README.md

blah Dockerfile frontend/ test_websocket.sh

I honestly don’t complete things other than filenames very much so I can’t speak to that, but I’ve found the experience of tab completing filenames to be very good.

5. nice default prompt (including git integration)

Fish’s default prompt includes everything I want:

- username

- hostname

- current folder

- git integration

- status of last command exit (if the last command failed)

Here’s a screenshot with a few different variations on the default prompt,

including if the last command was interrupted (the SIGINT) or failed.

6. nice history defaults

In bash, the maximum history size is 500 by default, presumably because computers used to be slow and not have a lot of disk space. Also, by default, commands don’t get added to your history until you end your session. So if your computer crashes, you lose some history.

In fish:

- the default history size is 256,000 commands. I don’t see any reason I’d ever need more.

- if you open a new tab, everything you’ve ever run (including commands in open sessions) is immediately available to you

- in an existing session, the history search will only include commands from the current session, plus everything that was in history at the time that you started the shell

I’m not sure how clearly I’m explaining how fish’s history system works here, but it feels really good to me in practice. My impression is that the way it’s implemented is the commands are continually added to the history file, but fish only loads the history file once, on startup.

I’ll mention here that if you want to have a fancier history system in another shell it might be worth checking out atuin or fzf.

7. press up arrow to search history

I also like fish’s interface for searching history: for example if I want to edit my fish config file, I can just type:

$ config.fish

and then press the up arrow to go back the last command that included config.fish. That’ll complete to:

$ vim ~/.config/fish/config.fish

and I’m done. This isn’t so different from using Ctrl+R in bash to search

your history but I think I like it a little better over all, maybe because

Ctrl+R has some behaviours that I find confusing (for example you can

end up accidentally editing your history which I don’t like).

8. the terminal doesn’t break

I used to run into issues with bash where I’d accidentally cat a binary to

the terminal, and it would break the terminal.

Every time fish displays a prompt, it’ll try to fix up your terminal so that you don’t end up in weird situations like this. I think this is some of the code in fish to prevent broken terminals.

Some things that it does are:

- turn on

echoso that you can see the characters you type - make sure that newlines work properly so that you don’t get that weird staircase effect

- reset your terminal background colour, etc

I don’t think I’ve run into any of these “my terminal is broken” issues in a very long time, and I actually didn’t even realize that this was because of fish – I thought that things somehow magically just got better, or maybe I wasn’t making as many mistakes. But I think it was mostly fish saving me from myself, and I really appreciate that.

9. Ctrl+S is disabled

Also related to terminals breaking: fish disables Ctrl+S (which freezes your terminal and then you need to remember to press Ctrl+Q to unfreeze it). It’s a feature that I’ve never wanted and I’m happy to not have it.

Apparently you can disable Ctrl+S in other shells with stty -ixon.

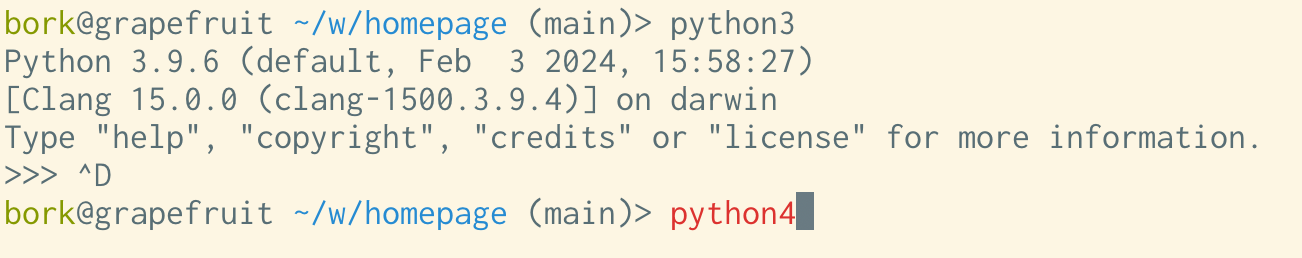

10. nice syntax highlighting

By default commands that don’t exist are highlighted in red, like this.

11. easier loops

I find the loop syntax in fish a lot easier to type than the bash syntax. It looks like this:

for i in *.yaml

echo $i

end

Also it’ll add indentation in your loops which is nice.

12. easier multiline editing

Related to loops: you can edit multiline commands much more easily than in bash (just use the arrow keys to navigate the multiline command!). Also when you use the up arrow to get a multiline command from your history, it’ll show you the whole command the exact same way you typed it instead of squishing it all onto one line like bash does:

$ bash

$ for i in *.png

> do

> echo $i

> done

$ # press up arrow

$ for i in *.png; do echo $i; done ink

13. Ctrl+left arrow

This might just be me, but I really appreciate that fish has the Ctrl+left arrow / Ctrl+right arrow keyboard shortcut for moving between

words when writing a command.

I’m honestly a bit confused about where this keyboard shortcut is coming from

(the only documented keyboard shortcut for this I can find in fish is Alt+left arrow / Alt + right arrow which seems to do the same thing), but I’m pretty

sure this is a fish shortcut.

A couple of notes about getting this shortcut to work / where it comes from:

- one person said they needed to switch their terminal emulator from the “Linux console” keybindings to “Default (XFree 4)” to get it to work in fish

- on Mac OS,

Ctrl+left arrowswitches workspaces by default, so I had to turn that off. - Also apparently Ubuntu configures libreadline in

/etc/inputrcto makeCtrl+left/right arrowgo back/forward a word, so it’ll work in bash on Ubuntu and maybe other Linux distros too. Here’s a stack overflow question talking about that

a downside: not everything has a fish integration

Sometimes tools don’t have instructions for integrating them with fish. That’s annoying, but:

- I’ve found this has gotten better over the last 10 years as fish has gotten more popular. For example Python’s virtualenv has had a fish integration for a long time now.

- If I need to run a POSIX shell command real quick, I can always just run

bashorzsh - I’ve gotten much better over the years at translating simple commands to fish syntax when I need to

My biggest day-to-day to annoyance is probably that for whatever reason I’m

still not used to fish’s syntax for setting environment variables, I get confused

about set vs set -x.

another downside: fish_add_path

fish has a function called fish_add_path that you can run to add a directory

to your PATH like this:

fish_add_path /some/directory

I love the idea of it and I used to use it all the time, but I’ve stopped using it for two reasons:

- Sometimes

fish_add_pathwill update thePATHfor every session in the future (with a “universal variable”) and sometimes it will update thePATHjust for the current session. It’s hard for me to tell which one it will do: in theory the docs explain this but I could not understand them. - If you ever need to remove the directory from your

PATHa few weeks or months later because maybe you made a mistake, that’s also kind of hard to do (there are instructions in this comments of this github issue though).

Instead I just update my PATH like this, similarly to how I’d do it in bash:

set PATH $PATH /some/directory/bin

on POSIX compatibility

When I started using fish, you couldn’t do things like cmd1 && cmd2 – it

would complain “no, you need to run cmd1; and cmd2” instead.

It seems like over the years fish has started accepting a little more POSIX-style syntax than it used to, like:

cmd1 && cmd2export a=bto set an environment variable (though this seems a bit limited, you can’t doexport PATH=$PATH:/whateverso I think it’s probably better to learnsetinstead)

on fish as a default shell

Changing my default shell to fish is always a little annoying, I occasionally get myself into a situation where

- I install fish somewhere like maybe

/home/bork/.nix-stuff/bin/fish - I add the new fish location to

/etc/shellsas an allowed shell - I change my shell with

chsh - at some point months/years later I reinstall fish in a different location for some reason and remove the old one

- oh no!!! I have no valid shell! I can’t open a new terminal tab anymore!

This has never been a major issue because I always have a terminal open somewhere where I can fix the problem and rescue myself, but it’s a bit alarming.

If you don’t want to use chsh to change your shell to fish (which is very reasonable,

maybe I shouldn’t be doing that), the Arch wiki page has a couple of good suggestions –

either configure your terminal emulator to run fish or add an exec fish to

your .bashrc.

I’ve never really learned the scripting language

Other than occasionally writing a for loop interactively on the command line, I’ve never really learned the fish scripting language. I still do all of my shell scripting in bash.

I don’t think I’ve ever written a fish function or if statement.

it seems like fish is getting pretty popular

I ran a highly unscientific poll on Mastodon asking people what shell they use interactively. The results were (of 2600 responses):

- 46% bash

- 49% zsh

- 16% fish

- 5% other

I think 16% for fish is pretty remarkable, since (as far as I know) there isn’t any system where fish is the default shell, and my sense is that it’s very common to just stick to whatever your system’s default shell is.

It feels like a big achievement for the fish project, even if maybe my Mastodon followers are more likely than the average shell user to use fish for some reason.

who might fish be right for?

Fish definitely isn’t for everyone. I think I like it because:

- I really dislike configuring my shell (and honestly my dev environment in general), I want things to “just work” with the default settings

- fish’s defaults feel good to me

- I don’t spend that much time logged into random servers using other shells so there’s not too much context switching

- I liked its features so much that I was willing to relearn how to do a few

“basic” shell things, like using parentheses

(seq 1 10)to run a command instead of backticks or usingsetinstead ofexport

Maybe you’re also a person who would like fish! I hope a few more of the people who fish is for can find it, because I spend so much of my time in the terminal and it’s made that time much more pleasant.