Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Some more CSS comics

I’ve been continuing to write pages about CSS! Here are 6 more.

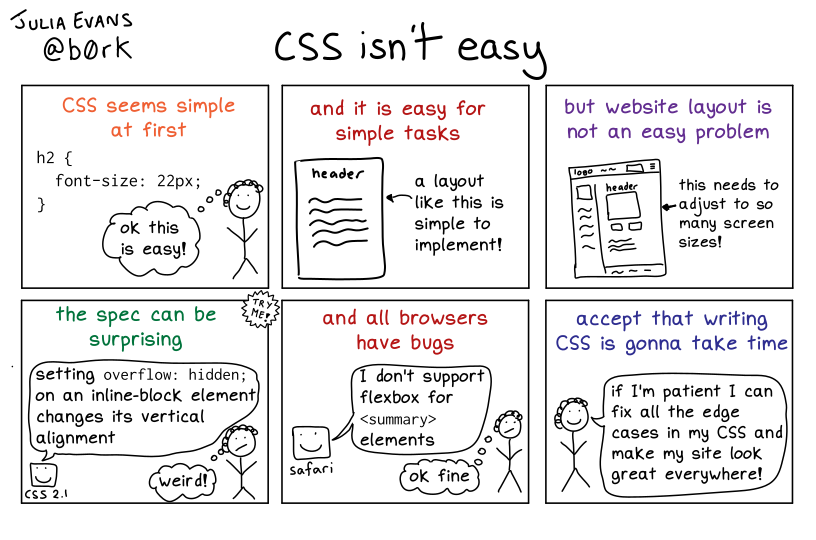

Two of them are about how to think about CSS in general (“CSS isn’t easy” and “backwards compatibility”), which is something I’m still trying to wrap my head around.

handling browser bugs is normal?

The fact that finding workarounds for browser bugs is kind of a normal part of writing CSS really surprised me – there’s this great repo called flexbugs which catalogs bugs in browser implementations of flexbox. A lot of the bugs are in IE which means (depending on your goals) that you can just ignore them, but not all! A bunch of the flexbugs are in Chrome or Safari or Firefox.

For example, I ran into flexbug #9 a few days ago, which is

that in Safari a <summary> element can’t be a flexbox, so instead you need to

put an extra div inside the <summary> to be the flex element.

In the past I would have reacted to this in a more grumpy way (WHY? NOOOOO? WHAT IS HAPPENING?!?! CSS?!?!?!). But this time I noticed that my site looked weird in Safari on my iPad, figured out after 30 minutes or so that it was a Safari bug, implemented a workaround, and it actually wasn’t that big of a deal!

I think this mindset of “oh, there’s a browser bug, oh well, I guess that happens sometimes!” is a lot healthier and more likely to result in success than getting mad about it.

there are a lot of ways CSS can go wrong

I think there are at least 3 different ways your CSS can be buggy:

- that element doesn’t have the styles applied that it should (for example

it’s supposed to be

background; bluebut it’sbackground: redinstead) - the element has the “right” styles applied, but those styles do something confusing / unexpected to me because of something I misunderstood about the CSS spec

- the element has the “right” styles applied and those styles do the right thing according to the spec, but the browser has a bug and isn’t implementing the spec correctly

Anyway, enough CSS musings, here are the comics :)

css isn’t easy

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/css-isnt-easy

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/css-isnt-easy

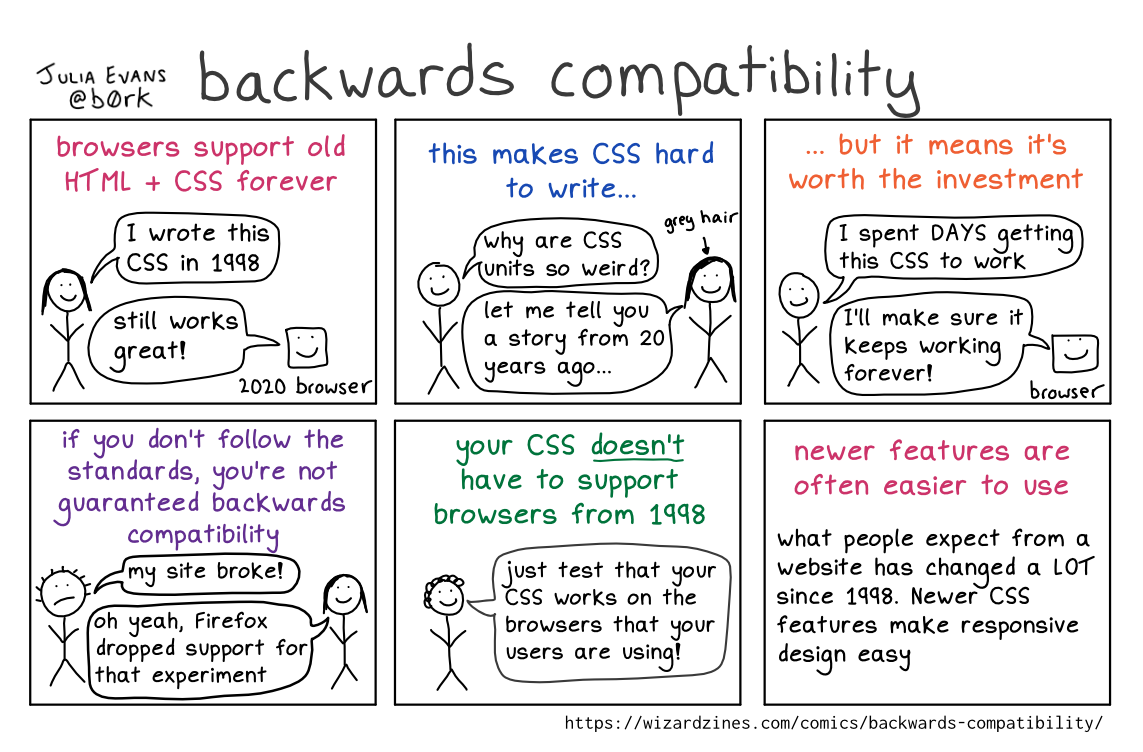

backwards compatibility

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/backwards-compatibility

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/backwards-compatibility

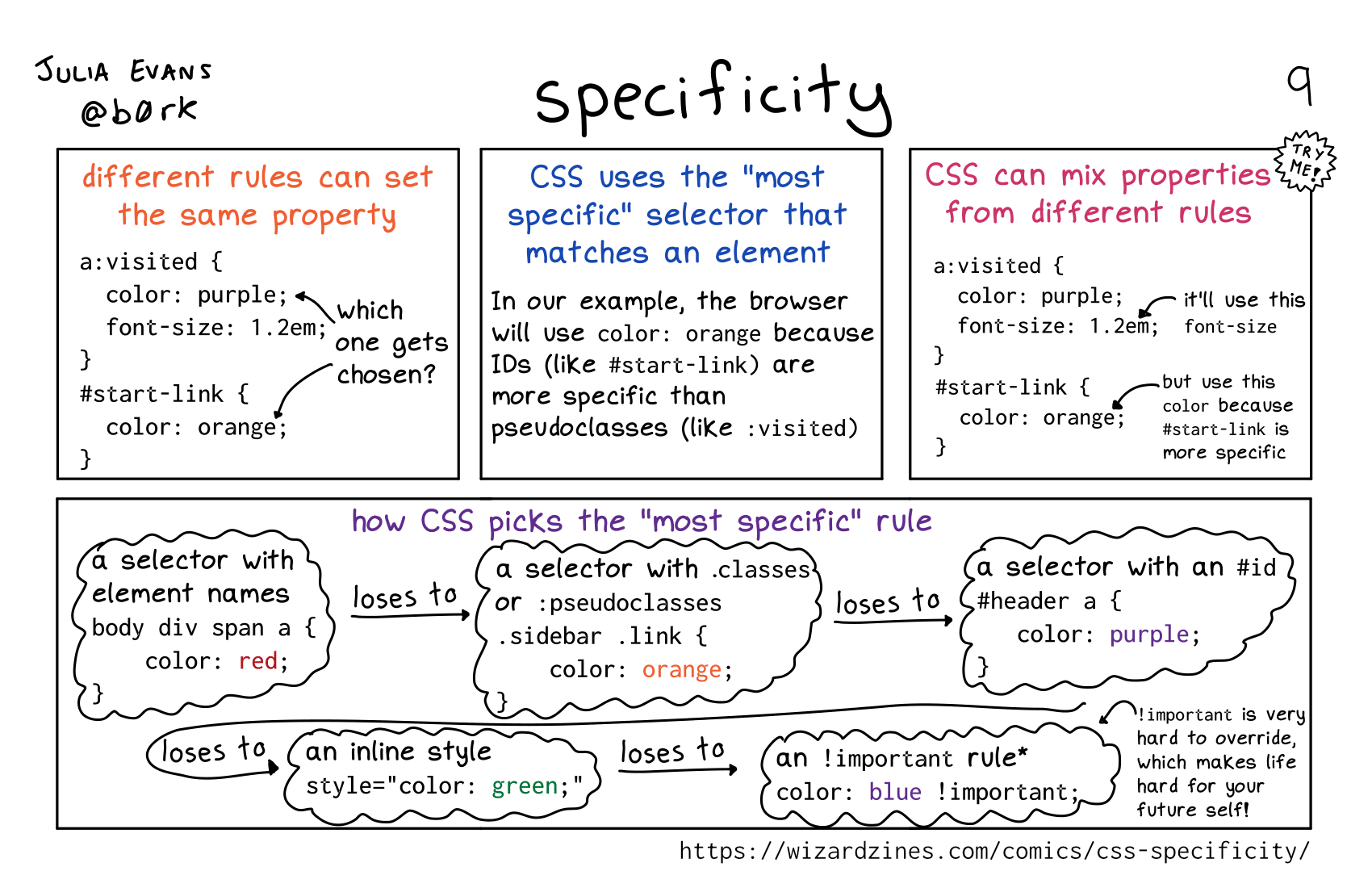

CSS specificity

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/css-specificity

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/css-specificity

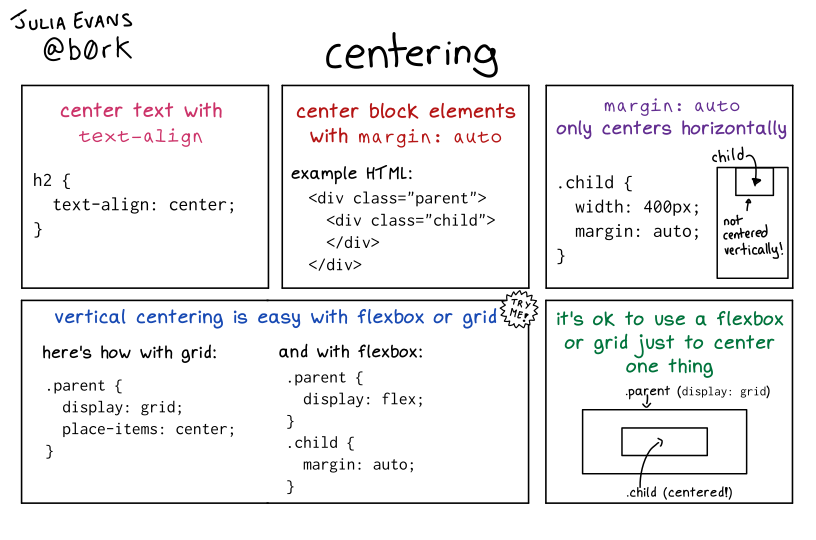

centering in CSS

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/css-centering

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/css-centering

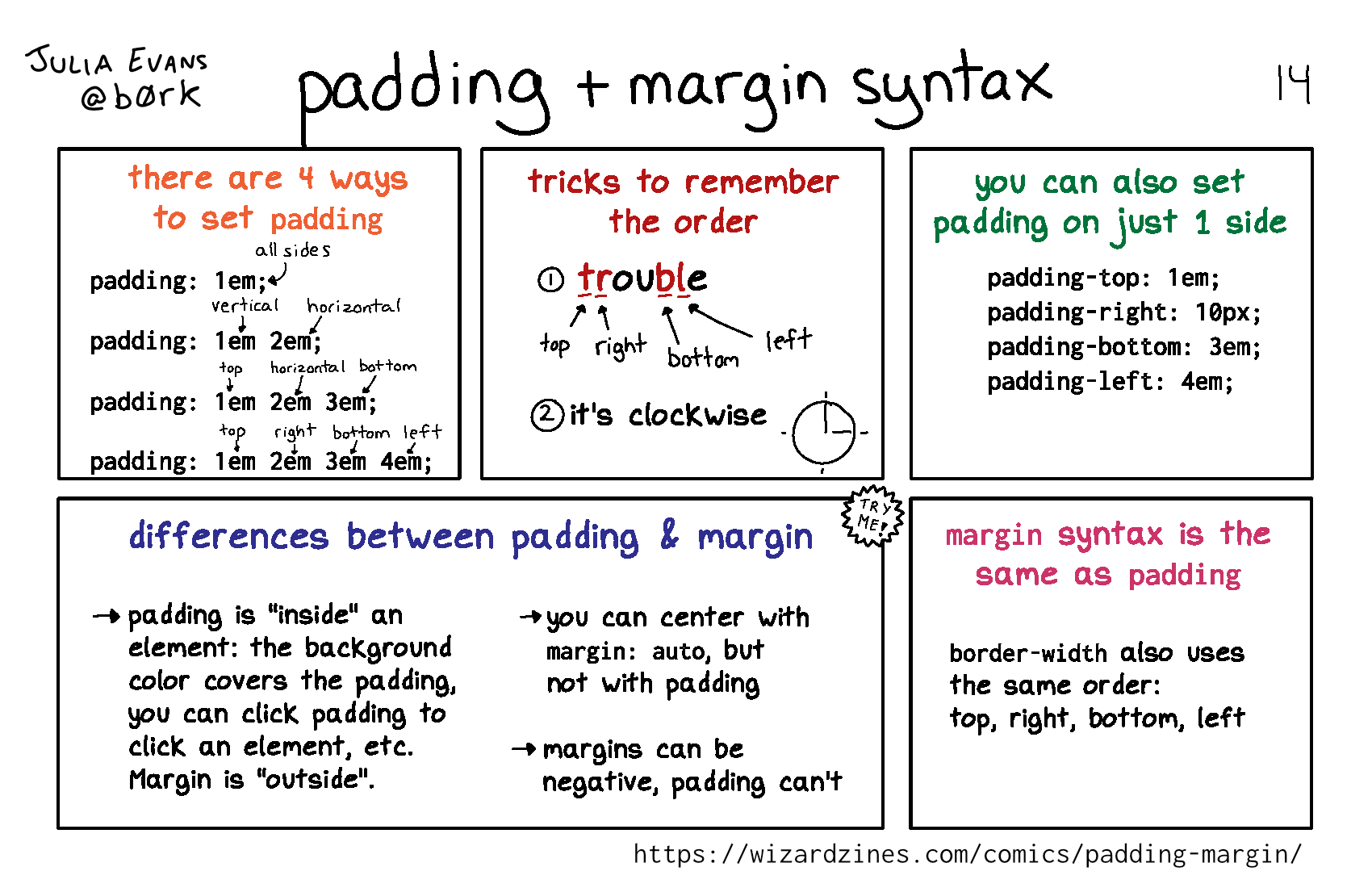

padding syntax

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/padding-margin

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/padding-margin

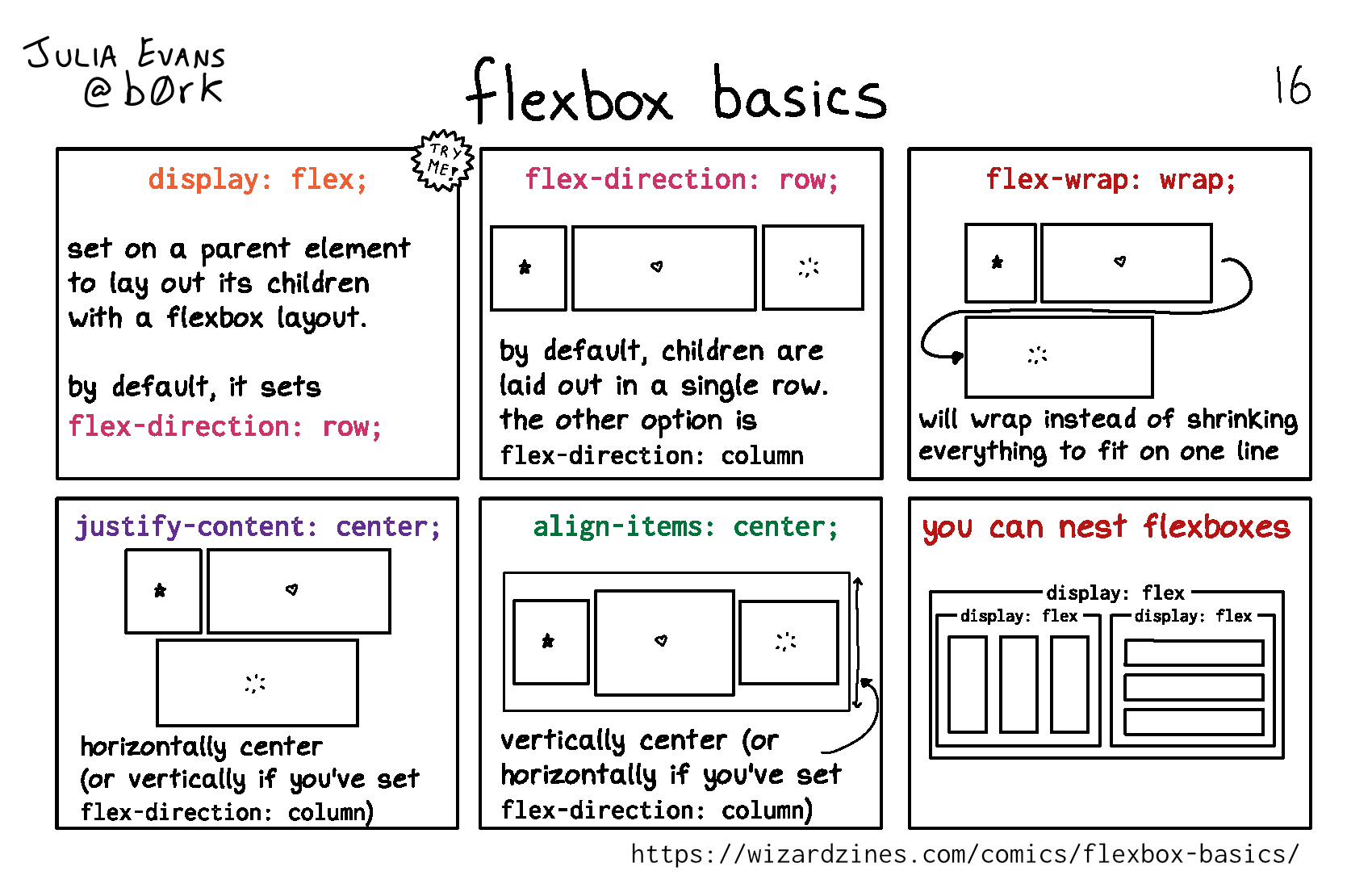

flexbox basics

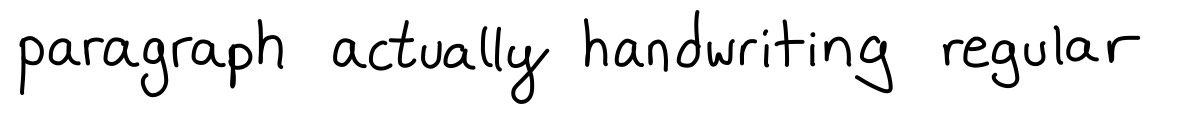

An attempt to make a font look more handwritten

I’m actually not super happy with the results of this experiment, but I wanted to share it anyway because it was very easy and fun to play with fonts. And somebody asked me how to do it and I told her I’d write a blog post about it :)

background: the original handwritten font

Some background: I have a font of my handwriting that I’ve been use in my zines for a couple of years. I made it using a delightful app called iFontMaker. They pitch themselves on their website as “You can create your handmade typeface in less than 5 minutes just with your fingers”. In my experience the ‘5 minutes” part is pretty accurate – I might have spent more like 15 minutes. I’m skeptical of the “just your fingers” claim – I used an Apple Pencil, which has much better accuracy. But it is extremely easy to make a TTF font of your handwriting with the app and if you happen to already have an Apple Pencil and iPad I think it’s a fun way to spend $7.99.

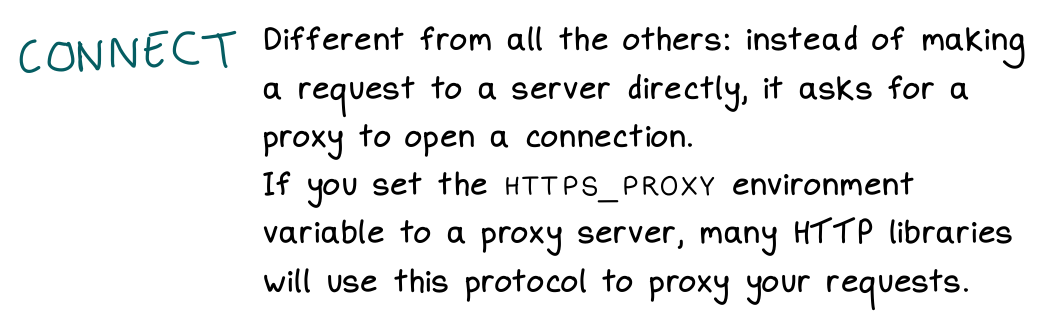

Here’s what my font looks like. The “CONNECT” text on the left is my actual handwriting, and the paragraph on the right is the font. There are actually 2 fonts – there’s a regular font and a handwritten “monospace” font. (which actually isn’t monospace in practice, I haven’t figured out how to make an actual monospace font in iFontMaker)

the goal: have more character variation in the font

In the screenshot above, it’s pretty obvious that it’s a font and not actual handwriting. It’s easiest to see this when you have two of the same letter next to each other, like in “HTTP’.

So I thought it might be fun to use some OpenType features to somehow introduce a little more variation into this font, like maybe the two Ts could be different. I didn’t know how to do this though!

idea from Tristan Hume: use OpenType!

Then I was at !!Con 2020 in May (all the talk recordings are here!) and saw this talk by Tristan Hume about using OpenType to place commas in big numbers by using a special font. His talk and blog post are both great so here are a bunch of links – the live demo is maybe the fastest way to see his results.

- a live demo: Numderline Test

- the blog post: Commas in big numbers everywhere: An OpenType adventure

- the talk: !!Con 2020 - Using font shaping to put commas in big numbers EVERYWHERE!! by Tristan Hume

- the github repo: https://github.com/trishume/numderline/blob/master/patcher.py

the main idea: OpenType lets you replace characters based on context

I started out being extremely confused about what OpenType even is. I still don’t know much, but I learned that you can write extremely simple OpenType rules to change how a font looks, and you don’t even have to really understand anything about fonts.

Here’s an example rule:

sub a' b by other_a;

What sub a' b by other_a; means is: If an a glyph is before a b, then replace the a with the glyph other_a.

So this means I can make ab appear different from ac in the font. It’s not

random the way handwriting is, but it does introduce a little bit of variation.

OpenType reference documentation: awesome

The best documentation I found for OpenType was this OpenType™ Feature File Specification reference. There are a lot of examples of cool things you can do in there, like replace “ffi” with a ligature.

how to apply these rules: fonttools

Adding new OpenType rules to a font is extremely easy. There’s a Python library

called fonttools, and these 5 lines of code will apply a list of OpenType

rules (in rules.fea) to the font file input.ttf.

from fontTools.ttLib import TTFont

from fontTools.feaLib.builder import addOpenTypeFeatures

ft_font = TTFont('input.ttf')

addOpenTypeFeatures(ft_font, 'rules.fea', tables=['GSUB'])

ft_font.save('output.ttf')

fontTools also provides a couple of command line tools called ttx and

fonttools. ttx converts a TTF font into an XML file, which was useful to me

because I wanted to rename some glyphs in my font but did not understand

anything about fonts. So I just converted my font into an XML file, used sed

to rename the glyphs, and then used ttx again to convert the XML file back into a ttf.

fonttools merge let me merge my 3 handwriting fonts into 1 so that I had all the glyphs I needed in 1 file.

the code

I put my extremely hacky code for doing this in a repository called

font-mixer. It’s like 33 lines of code and I think it’s pretty straightforward. (it’s all in run.sh and combine.py)

the results

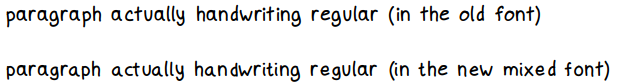

Here’s a small sample the old font and the new font. I don’t think the new font “feels” that much more like handwriting – there’s a little more variation, but it still doesn’t compare to actual handwritten text (at the bottom).

It feels a little uncanny valley to me, like it’s obviously still a font but it’s pretending to be something else.

And here’s a sample of the same text actually written by hand:

It’s possible that the results would be better if I was more careful about how I made the 2 other handwriting fonts I mixed the original font with.

it’s cool that it’s so easy to add opentype rules!

Mostly what was delightful to me here is that it’s so easy to add OpenType rules to change how fonts work, like you can pretty easily make a font where the word “the” is always replaced with “teh” (typos all the time!).

I still don’t know how to make a more realistic handwriting font though :). I’m still using the old one (without the extra variations) and I’m pretty happy with it.

Some CSS comics

Hello! I’ve been writing some comics about CSS this past week, and I thought as an experiment I’d post them to my blog instead of only putting them on Twitter.

I’m going to ramble about CSS at the beginning a bit but you can skip to the end if you just want to read the comics :)

why write about CSS?

I’ve been writing a tiny bit more CSS recently, and I’ve decided to actually take some time to learn CSS instead of just flailing around and deciding “oh no, this is impossible”.

CSS feels a little like systems programming / Linux to me – there are a lot of counterintuitive facts that you need to learn to be effective with it, but I think once you learn those facts it gets a lot easier.

So I’m writing down some facts that I found counterintuitive when learning CSS,

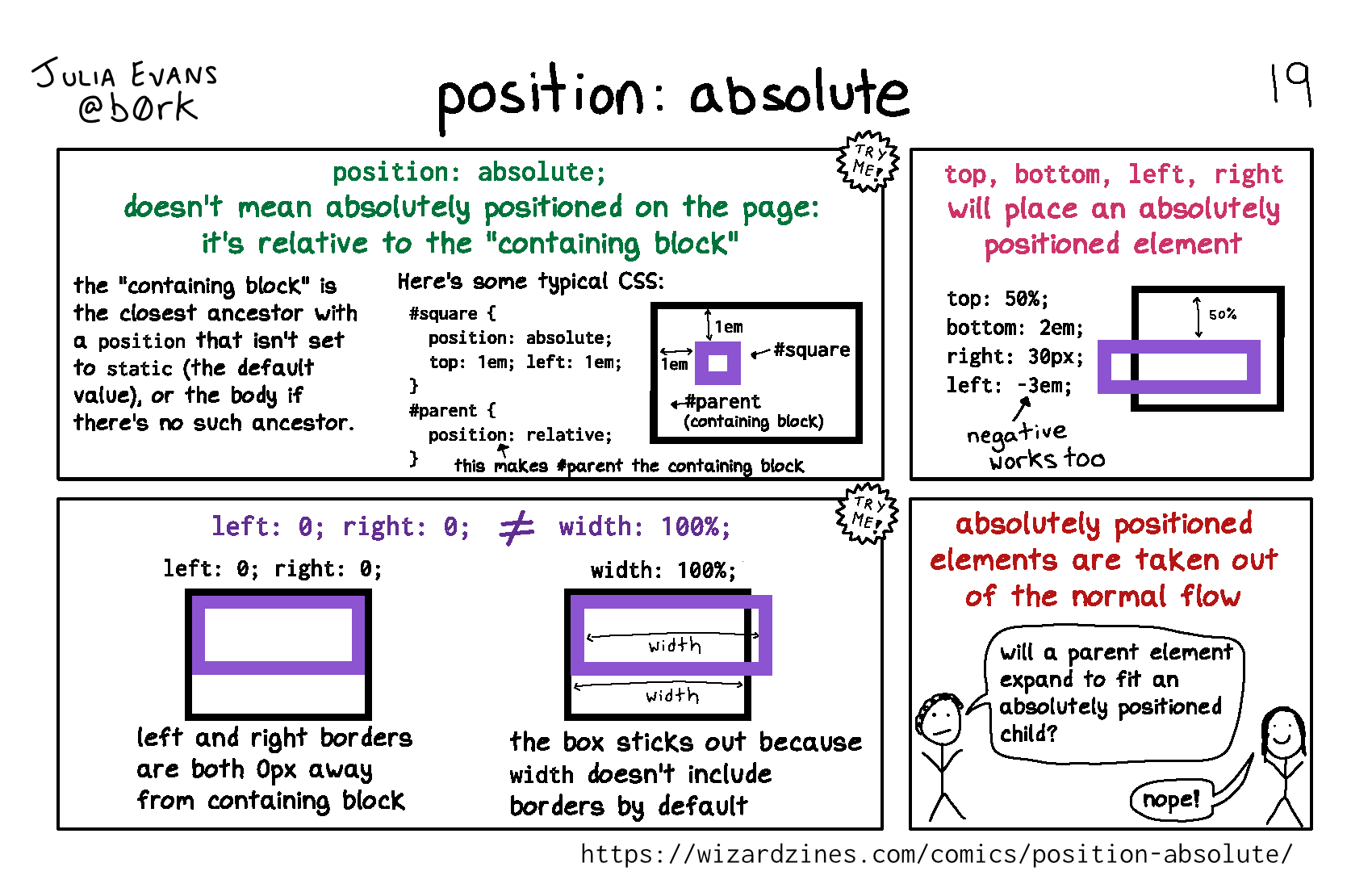

like the fact that position: absolute isn’t absolute!

why try to read the specs?

I’ve been having a lot of fun reading through the CSS2 spec and finding out that some things about CSS that I was intimidated by (like selector specificity) aren’t as complicated as I thought.

I think reading (parts of) the CSS specs is fun because I’m so used to learning CSS by reading a lot of websites which sometimes have conflicting information. (MDN is an incredible resource but I don’t think it’s 100% always correct either.)

So it’s fun to read a more authoritative source! Of course, it’s not always true that the CSS specs correspond to reality – browser implementations of the specs are inconsistent.

But expecially for parts of CSS that are older & better-established (like the

basics of how position: absolute works) I like reading the specs.

how are the CSS specs organized?

CSS used to be defined by a single specification (CSS2), but as of CSS 3 each part of CSS has its own specification. For example, there’s a CSS 3 specification for colours.

Here are the links I’ve been using:

- there’s a PDF of the CSS2 spec here

- CSS Snapshot 2018 lists all the CSS specifications as of 2018, which is where I’ve been looking for links to the CSS 3 specifications

- Understanding the CSS Specifications is an explanation of how to approach reading the CSS specs. For example, it recommends reading CSS sizing which I haven’t tried reading yet.

I’ve been kind of alternating between the CSS 2 spec and the CSS 3 specs – because the CSS 2 spec is smaller, I find it easier to digest and understand the big picture of how things are supposed to work without getting lost in a lot of details.

a few comics

Okay, here are the comics! As always when I start working on a set of comics / a potential zine, there’s no specific order or organization.

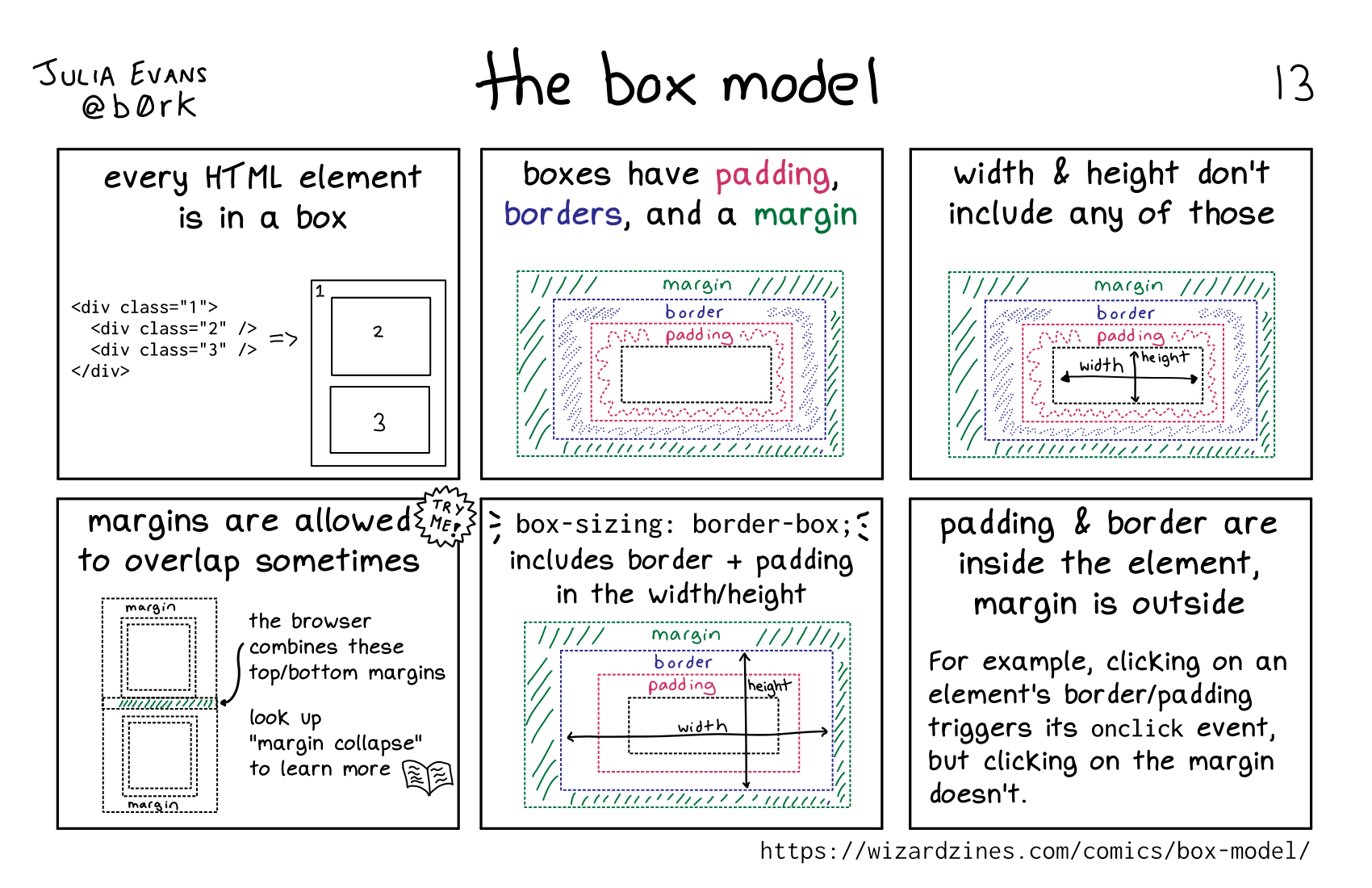

the box model

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/box-model

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/box-model

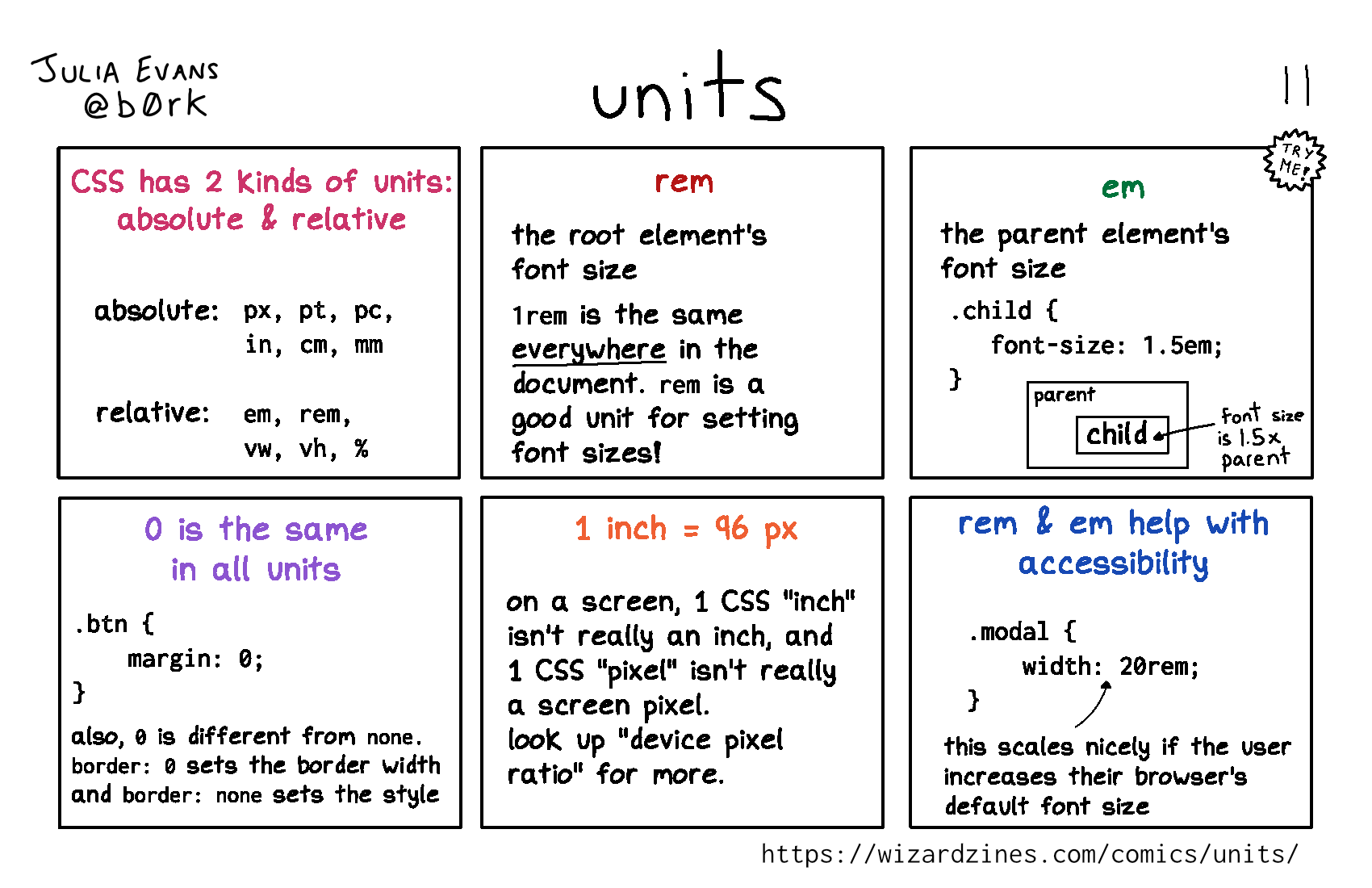

CSS units

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/units

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/units

Reference material: I found this section on lengths from “CSS Values and Units Module Level 3” pretty straightforward.

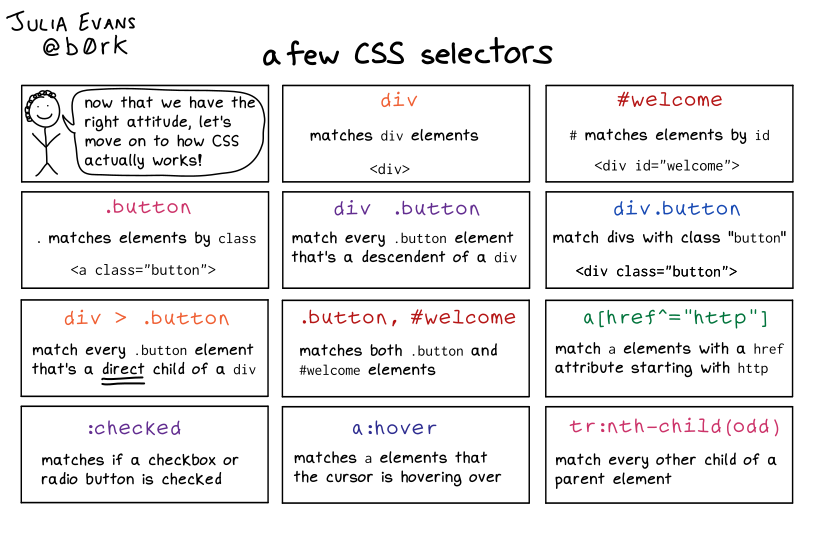

selectors

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/selectors

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/selectors

Reference material: section 6.4.1 to 6.4.3 from the CSS 2 spec.

position: absolute

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/position-absolute

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/position-absolute

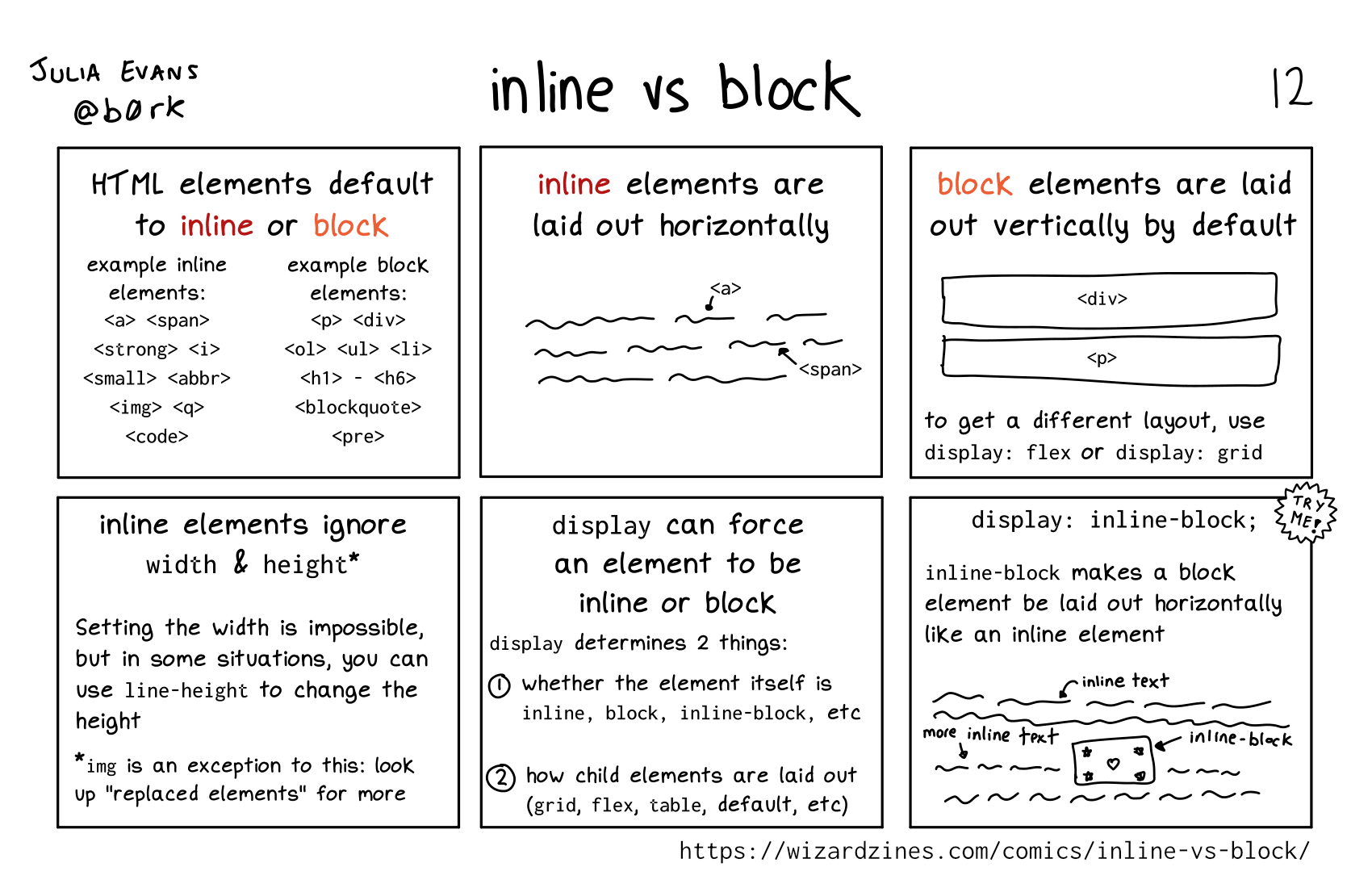

inline vs block

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/inline-vs-block

Permalink: https://wizardzines.com/comics/inline-vs-block

One piece of errata for this one: you actually can set the width on an inline element if it’s a “replaced” element