Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

New zine: Hell Yes! CSS!

Hello! Last Friday I released a new zine called Hell Yes! CSS!

You can get it for $12 here: https://wizardzines.com/zines/css, or get a 9-pack of all my zines here for $88.

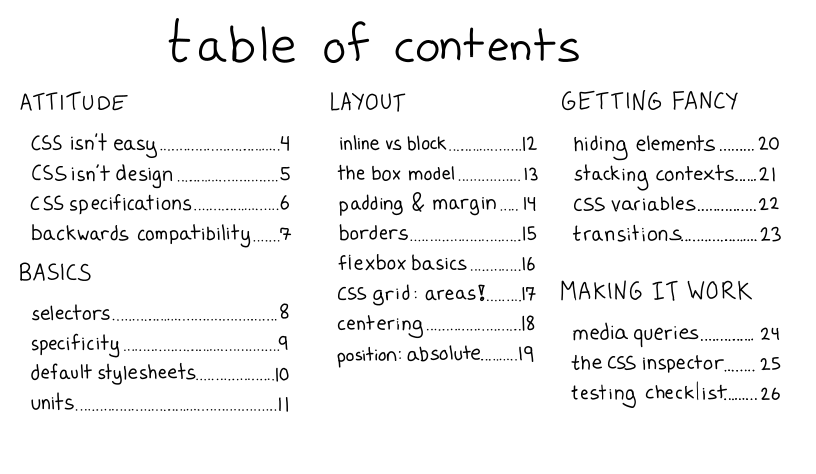

Here’s the cover and table of contents:

why CSS?

I’ve been writing CSS on and off (mostly off) for about 15 years. For almost all of that time, CSS really felt impossible to me – every time I did a seemingly simple task (like the classic “center a div”), I had to Google how to do it, then it wouldn’t work the way I expected, than I’d change random things, and eventually the thing would kind of sort of work. Then I’d never really internalize what I’d learned and I’d start again from scratch the next time. I didn’t write CSS very often, and because it seemed “impossible”, I never put the effort in to get better.

there’s a better way

But this year, I learned a different way to approach CSS. I’d hired Melody Starling to design & implement https://wizardzines.com for me. In addition to being a great designer, I saw that their approach to writing CSS was COMPLETELY DIFFERENT from mine.

They:

- didn’t Google basic CSS facts, if they needed to center something they would just center it

- could do things that I thought were “impossible” (like using position: absolute) quickly and have them work the first thing

- debugged CSS issues quickly & seemed to clearly understand why the changes they made fixed the problem. They never made random changes.

Of course, a lot of this comes from their extensive experience writing CSS and I couldn’t just magically import their experience into my brain. But I realized something important.

CSS isn’t arbitrary, it’s just counterintuitive sometimes

Here’s one example. For my first 13 years of occasionally writing CSS poorly, I

didn’t understand how position: absolute worked. I thought it positioned things

absolutely on the page (isn’t that what the absolute means??), but sometimes

I’d see things that made that seem wrong, so I was just confused and sad about

it.

But then I learned something that changed everything for me: position: absolute

actually positions elements relatively to the closest positioned parent.

Here’s a codepen that shows an example of what I mean. It shows how to position 4 stars at the 4 corners of a box (it’s actually very easy!!) https://codepen.io/wizardzines/pen/ZEOzqaN

Actually taking the time to understand how position: absolute worked didn’t

take that long (I just needed to learn 1 fact!!) and it meant that now I no

longer have to blindly copy paste CSS to absolutely position things. I can

figure them out myself, and I’m a lot more faster and confident.

learning some CSS fundamentals can help a lot

Hell yes! CSS! explains some of the CSS fundamentals that have helped me get more WAY more confident with CSS this year. Since I learned them, I’ve been able to quickly make a lot of fun small websites with confidence, and CSS bugs have been a lot more tractable. I’ve been able to actually reason through a lot of my CSS problems – no more throwing spaghetti at the wall and hoping my website eventually looks the way I want! (ok, let’s be honest, there’s still a little of that, but it’s been WAY BETTER).

and so does having the right attitude

The other thing Hell Yes! CSS! talks about a little bit is attitude! CSS can absolutely be difficult and frustrating. But did you know that if you write standards-compliant CSS, then browser backwards compatibility will ensure that your website keeps working FOREVER?!

So if you spend the effort to get your CSS right once, it’ll keep looking great for the next 10 years. I’ve changed my attitude towards CSS from “UGH WHY! CSS BAD! I AM SAD!” to “oh, interesting! Why doesn’t this work? I can probably figure it out!” and it’s helped a LOT.

So that’s what this zine is about!

I also put together some CSS examples

The zine has a lot of counterintuitive CSS facts, and I know from experience that it’s very difficult to learn hard things just by reading some text – I always need to play around with some actual real CSS to understand how it works.

So I built CSS examples (https://css-examples.wizardzines.com/) to help with this a little bit. It has about 20 examples illustrating various CSS facts. Some of them are relatively straightforward (like the one on border-radius), and some of them are pretty surprising and confusing at first, like this one on how left: 0; right: 0 is different from width: 100%; and this super weird thing about how inline-block elements are aligned differently depending on whether they have text in them.

You can edit them all using the amazing https://codepen.io/ (click “Edit on Codepen”), and a lot of them have specific suggestions for changes to try to understand how the example works better.

what’s next: a zine on bash scripting!

I have a zine on bash scripting called Bite Size Bash almost finished, and I’m going to release it pretty soon.

Another idea I have for the future is to put together a bunch of “CSS études” – basically “here’s a design, implement this in CSS”. If this already exists, I’d love to know about it!

Here’s a link to where to get Hell Yes! CSS! again :). As usual if you’re in a country where $12 USD is a lot of money, I have some country-specific discounts – if you click the link you should see them.

Day 8: Start with something that works

Today at RC I’m a little stuck so here’s a very short reflection on how to do hard programming problems :)

I was talking to a friend yesterday about how to do programming projects that are a bit out of your comfort zone, and I realized that there’s a pattern to how I approach new-to-me topics! Here I’m especially thinking about little side projects where you want to get the thing done pretty efficiently.

When I start on a new project using some technology I haven’t worked with before, I often:

- Find some code on the internet that already does something a little like what I want

- Incrementally modify that code until it does what I want, often completely changing everything about the original code in the process

Here are a couple of quick thoughts about this process:

it’s important that the initial code works

Often when I’m out looking for examples, I’ll find a lot of code that I can’t get to work quickly, often because the code is kind of old and things have changed since then. Whenever possible, I try to find code that I can get to work on my computer pretty quickly.

It’s been pretty helpful to me to give up relatively quickly on code that I can’t get to work right away and look for another example – often there is something out there that’s more recent and that I can get to work more quickly!

you have to be able to incrementally change the code into what you want

Today I’ve been working with some neural network code, and one thing I’m really struggling with for the last couple of days is that I find it pretty easy to find somewhat relevant Jupyter notebooks that do RNN things, and pretty hard to modify those examples to do something closer to what I want. They keep breaking and I then don’t know how to fix them.

Last week I was working on a Rails app, which I think is something that’s very

easy to incrementally change into the program you want: rails new gives you a

webserver that does almost nothing, but it works! And then you just need to

change it one tiny step at a time into the website you want to build.

examples of “something that works”

- If you want to write a window manager, tinywm is a window manager in 50 lines of C!

- this tiny kernel written in Rust that does nothing was a fun starting point for an operating system https://github.com/charliesome/rustboot (probably it’s not a good starting point today)

rails new, like I talked about above- I love that https://glitch.com/ projects let you “view source” on the backend of any Glitch project

- Jupyter notebooks, like these great NLP tutorials by Allison Parrish

that’s all!

I think little starting points like this are so important and can be really magical. Finding the right starting point can be hard, but when I find a good one it makes everything so much easier!

How do you write simple explanations without sounding condescending?

Sumana Harihareswara wrote an interesting blog post Plain Language Choices recently, about writing about complicated topics using simple language and how it can sometimes come off as condescending.

I really like explaining complicated topics while trying to avoid unnecessary jargon, and I realized that I’ve thought a lot about how to do it well. So here are a bunch of things I try to do when I use simple language to avoid coming off as condescending.

use some jargon to give the reader search terms

Sometimes I see writing that completely avoids all jargon and instead substitutes simple language for all “jargon”-y words.

I like to include some jargon in my explanations because otherwise it’s impossible for the reader to search & learn more about the concept they’re trying to learn about.

write (mostly) true explanations

Something else I see sometimes in ELI5-type explanations is an explanation in plain language that’s not actually true in a useful way. I’m pretty sympathetic to why people do this – it’s super hard to write simple explanations that are also true!

And actually sometimes when I’m trying to write down a simple/clear explanation for a concept, I realize that I don’t actually understand the concept as well as I thought and that I’m not able to explain it. That’s okay!

I think there are a few options here:

- try to say only things that are true (or at least which are a useful model for how the world works even if they’re not 100% true)

- write things that are not really true / that you’re not sure of, but point out that they may not be true (“I think it works like X, but I realize now that it might be Y instead, I’m not sure!“)

only use “fun” visual elements on explanations that are actually well written & easy to understand

This happens more with visual aids than with simple language but I’ll include it anyway. Sometimes I see explanations which have “fun” elements to it to make it them seem more approachable where the explanation itself is still pretty unclear.

I try to be careful about this in my own work – I try to only attach “fun” elements (like a fun illustrated cover) to explanations that I’ve spent a lot of time on making really clear. Basically to me “fun” things are a signal that the content itself is really clear/accessible, and I try to not misuse that signal.

I think why’s poignant guide to ruby is a nice example of something that’s fun and clear and which has helped a lot of people learn Ruby.

Another nice example of this is: I know someone who got her master’s thesis printed as a paperback book and illustrated with some great drawings related to the topic of her thesis (trans represensentation in media). It’s called “I’m supposed to relate to this?”, here’s the paperback.

I ended up reading the whole thing because, in addition to having the fun illustrations, her master’s thesis was really well written and interesting! The fact that she did the work to print a paperback book of her thesis and get it illustrated was a sign that she’d worked on making the writing accessible to a non-academic audience, and it was true!

tell a relevant story

Stories can really help people learn! For example, something I’ve done a lot on this blog is talk about a problem I ran into in the course of my job and what I did to solve that problem.

Some kinds of stories that I think work well:

- a real problem that someone ran into, to motivate why the concept is interesting / important to learn

- something that’s happening on a computer, framed as a “story” (for example https://howdns.works/ tells a story about how DNS works. Everything in the story literally corresponds to exactly what happens when you make a DNS query)

Sometimes I see stories used to explain concepts that don’t fit into either of these and feel kind of pasted on, like they’re there to help the concept seem “fun” but don’t actually illustrate the concept or motivate why it might be useful to learn it.

have a specific audience in mind

I try to write relatively simple explanations, but when I write I also generally assume a lot of knowledge on the part of my audience.

Sometimes I see explanations of complicated concepts that start with explaining the very basics of the topic. This usually isn’t that effective: if someone is trying to understand some super technical aspect of containers, they probably understand the basics of containers already!

“Have an audience” is more of a general writing tip so I’ll leave it at that.

on using simple language as a joke for people who already understand the idea

Here’s a very fun explanation of a complicated thing using simple language: Gödel’s Second Incompleteness Theorem Explained in Words of One Syllable.

On one hand, this is fun! I enjoyed reading it. On the other hand, I think the main audience for this is probably people who already more or less understand Gödel’s Second Incompleteness Theorem.

For example, someone pointed out that “if math is a not a load of bunk” in this text is code for “Peano arithmetic is consistent” with (“math” being “Peano arithmetic” and “not a load of bunk” meaning “consistent”). Which I find very charming, but also I found it a little hard to decode when reading it.

And (as we talked about before about jargon), if you know that “Peano arithmetic is consistent” is the relevant bit of jargon, you can find all kind of fascinating things, like a blog post by John Baez from 2011 discussing an attempted proof that Peano arithmetic was inconsistent)

(I’m also reminded here of the XKCD up goer five, which is very delightful, but I don’t think I learned anything about spaceships from reading it)

that’s all!

I’d love to hear more thoughts on this – I think there are probably more ways that simple explanations can feel condescending that I’ve missed!

I really don’t think they need to feel condescending though – to me the point of writing a clear/simple explanation is usually that I think the idea is not actually fundamentally that complicated and so I’m just explaining it in a way that’s exactly as complicated as it needs to be.

A new way I'm getting feedback on my zines: beta readers!

In the last few weeks I’ve been editing 2 zines and getting them ready to release: one on CSS and one on bash.

I have a lot of ways I get feedback on my zines to make them better, including:

- post individual pages on Twitter and see what people say

- hire someone to go over the zine in depth and see what they find confusing (I do this with my friend Dolly, who always points out a million things that don’t make sense and helps me come up with ideas for new pages on topics that I’ve totally forgotten to explain)

- hire a technical reviewer

- ask a friend to casually look at parts of it and see what they think (the diagrams in the SQL zine are thanks to my friend Anton who told me “these diagrams are confusing, what if you did them like this instead?”)

- ask my partner to read it

- hire a copy editor near the end

But I still felt like I wasn’t getting quite enough feedback about which parts of the zine were confusing and needed to be made more clear.

So this round of zine editing, I had an idea: what if I recruited 10-20 beta readers and got their thoughts? I thought this worked really well, so here’s my process for doing this in case it’s useful for someone else writing a book.

(and since a few people have offered: I’ll say to start out that I’m not looking for new beta readers right now, but I really appreciate everyone who has helped with this!)

step 1: email my mailing list and ask for beta readers

I sent a quick note out to part of my mailing list, like this:

If you’d be interested in reading through a draft of the zine and sending me some feedback about which parts are confusing, email me at REDACTED! I’m especially interested in hearing from people who know some basic CSS, but still get really confused & frustrated every time they try to get something done.

Anyone who gives me beta reader feedback on the zine will get a free copy of the zine when it comes out, as a thank you :)

Julia

I think there were 3 important things here:

- the number of people I sent it to: I sent this to about 300-600 people, and about 5% of the people I emailed replied – 10-30 beta readers. I think that gave me a good range of feedback and that I’d aim for a similar number in the future. I think that if I emailed way more people (like 2000), it would be hard to manage emailing all of them and digesting all the feedback

- saying who specifically I want feedback from. In this case, I said that I wanted to hear from “people who know some basic CSS, but still get really confused & frustrated every time they try to get something done.” I think this is important because it lets me focus on feedback from people who are in the audience for the zine.

- ask people to briefly summarize their experience with the topic. This is something I didn’t ask for, but that most people naturally did on their own when emailing me – they’d write a sentence or two about their experience with CSS. I think that next time I’d ask people to do this because I found it VERY helpful to understand a little bit about the person’s experience when reading their feedback.

step 2: explain what kind of feedback I want

I think this was the most important step. I wanted a really specific kind of feedback from my beta readers (to tell me which parts of the zine were confusing), and I knew that I wouldn’t get it if I didn’t ask for it specifically. So I wrote a pretty detailed email explaining the kinds of feedback I wanted and the kinds of feedback I didn’t want.

I also tried to be respectful of people’s time – I knew that people were busy, so I said that I appreciated any amount of feedback, even if they didn’t have time to read the whole zine.

Hi NAME! (sometimes a quick sentence personal to them here, like “You’re definitely who I want to hear from – I partly wrote this for people who wrote CSS 10 years ago and haven’t learned anything new since then”)

Here’s a link to download the current zine draft: https://www.dropbox.com/REDACTED (please don’t share it!)

Any amount of feedback really helps me – if you just read 5 pages of the zine and only have 2-3 small pieces of feedback, please send it! I’d like to get the feedback by Saturday. You can either leave comments on Dropbox or just download the PDF and send me an email with a bunch of notes like “page 6: I didn’t understand XYZ”. Whatever’s easier for you!

here’s the kind of feedback that would help me the most:

- Things you found confusing. Things like:

- On page 3 it uses the term “inline” and I had to look up what that meant

- Nothing on page 10 made sense to me, I was just really confused

- Questions you have (either big questions like “what even is the point of this feature at all?” or small questions like “what is that code supposed to output?”)

- Specific things you learned! (for example, “I never understood what X syntax meant, and now I get it!”)

I’m generally not looking for:

- Things that you think someone else might find confusing, but that you yourself understand. I find that most people (including me, which is why I’m asking for this feedback!) aren’t great at simulating what someone else might find confusing.

- Technical review (I have someone else doing that and I find it’s simpler not to crowdsource tech review)

(though if you have something in these categories that you think is especially important, I’m happy to hear it!)

thanks again, and I’m excited to hear what you have to say!

Julia

step 3: consolidate the feedback!

People REALLY delivered and gave me really great feedback! I wasn’t sure if people responding would stick to the guidelines of “I found this confusing”, “here’s a question I have”, and “here’s something I learned”, but almost everyone did!

For both zines I gave people a pretty short deadline, about 6 days. So about a week later I went through all the feedback and organized everyone’s comments.

Pretty much everyone had organized their comments by page, so I created a text file that looked like this:

Page 10: specificity

NAME 1: some feedback

NAME 2: more feedback

NAME 2: a different point

Then I wrote a Python script to put all the comments for each page into the Trello card for that page (where I’ve been putting all the feedback I get from everyone)

a side excursion into Dropbox’s comments API

One small surprising thing that initially I didn’t expect is: I’d given everyone a Dropbox link to download the zine, and I’d forgotten that Dropbox has a commenting feature. So people who happened to have a Dropbox account would comment inside the Dropbox commenting feature.

I was a bit confused about how to handle this at first, because it turns out that for some reason that page renders extremely slowly on my laptop and so it was almost impossible to copy the comments out.

But then I remembered that I’m a programmer, so I:

- went into the network tab and reloaded the page

- found the request for the

list_commentsendpoint (or whatever it was called). - right clicked, clicked ‘copy as cURL`

- pasted it into my terminal, and voila! I had a JSON file of all the comments! Way easier than manually copying and pasting everything.

- wrote a little Python script to format the comments into a text file in a format I could use

step 4: look for patterns

Unsurprisingly, there were a lot of patterns in the feedback – most pages had feedback from maybe 5 people, and there were a few places where everyone would be confused about the exact same thing. This was SO HELPFUL because it was a clear sign that I definitely needed to change it.

Of course, sometimes people disagreed – sometimes one person would say something “this is really clear and I learned X Y Z from this page” and another person would say “this is very confusing, I have all these questions”. In cases like that, I usually tried to think about which person was closer to who I thought the audience for the zine was (which is why it’s so helpful to get a sense for each person’s background!), as well as always trying to fix the confusing thing if I could find a way to do it.

step 5: make the changes

Some confusing things were easy to fix, like “there’s a footnote here and I can’t figure out what it refers to”, or “you talk about ‘css reset’ stylesheets” but the explanation makes no sense”.

Some were harder, for example I have a page about stacking contexts that I

knew was confusing, and the beta readers confirmed it was in fact pretty

confusing. I think the root cause here is that stacking contexts might be

actually literally impossible to explain in 100 words / 6 panels, so I

approached problems like that by finding some simpler concept I could explain

in a small space, like “if z-index isn’t working the way you expect, the

reason is probably that you have 2 elements in different stacking contexts”.

One of the biggest changes I made to the CSS zine after getting the beta reader feedback was to add some examples (https://css-examples.wizardzines.com) focused on things that the beta readers had found confusing and mark the panels which have associated examples with a little “try me!” icon.

it really helped me feel more confident about the zine!

I always have this moment of anxiety when I release a new zine like “OH NO MAYBE THIS IS AWFUL AND NOBODY WILL UNDERSTAND ANYTHING”. Getting feedback from the beta readers has helped with this – because people both told me what they learned and what questions they had, I could see that a lot of the parts of the zine weren’t that confusing and that I was getting across a lot of the information that I’d hoped to get across.

that’s all!

Thanks so much to everyone who was a beta reader for these two zines (you know who you are!). I should say that I’m not looking for new beta readers now, but if you’re on my saturday comics mailing list, you might get an email from me at some point asking if you’re interested in being a beta reader :)

I'm doing another Recurse Center batch!

Hello! I’m going to do a batch (virtually) at the Recurse Center, starting on Monday. I’ll probably be blogging about what I learn there, so I want to talk a bit about my plans!

I’m excited about this because:

- I love RC, it’s my favourite programming community, and I’ve always been able to do fun programming projects there.

- they’ve put a lot of care into building a great virtual experience (including building some very fun custom software)

- there’s a pandemic, it’s going to be cold outside, and I think having a little bit more structure in my life is going to make me a lot happier this winter :)

what’s the Recurse Center?

The Recurse Center (which I’ll abbreviate to “RC”) is a self-directed programming retreat. It’s free to attend.

A “batch” is 1 or 6 or 12 weeks, and the idea is that during that time, you:

- choose what things you want to learn

- come up with a plan to learn the things (often the plan is “do some kind of fun project”, like “write a TCP stack”)

- learn the things

Also there are a bunch of other delightful people learning things, so there’s lots of inspiration for what to learn and people to collaborate with. There are always people who are early in their programming life and looking to get their first programming job, as well as people who have been programming for a long time.

Their business model is recruiting – they partner with a bunch of companies, and if you want a job at the end of your batch, then they’ll match you with companies, and if you accept a job with one of those companies then the company pays them a fee.

I won’t say too much more about it because I’ve written 50+ other posts about how much I love RC on this blog that probably cover it :)

some ideas for what I’ll do at RC

Last time I did RC I had a bunch of plans going in and did not do any of them. I think this time it’ll probably be the same but I’ll list my ideas anyway: here are some possible things I might do.

- learn Rails! I’ve been making small websites for a very long time but I haven’t really worked as a professional web developer, and I think it might be fun to have the superpower of being able to build websites quickly. I have an idea for a silly website that I think would be a fun starter rails project.

- experiment with generative neural networks (I’ve been curious about this for years but haven’t made any progress yet)

- maybe finish up this “incidents as a service” system that I started a year and a half ago to help people learn by practicing responding to weird computer situations

- deal with some of the rbspy issues that I’ve been ignoring for months/years

- maybe build a game! (there’s a games theme week during the batch!)

- maybe learn about graphics or shaders?

In my first batch I spent a lot of time on systems / networking stuff because that felt like the hardest thing I could do. This time I feel pretty comfortable with my ability to learn about systems stuff, so I think I’ll focus on different topics!

so that’s what I’ll be writing about for a while!

I’m hoping to blog more while I’m there, maybe not “every day” exactly (it turns out that blogging every day is a lot of work!), but I think it might be fun to write a bunch of tiny blog posts about things I’m learning.

I’m also planning to release a couple of zines this month – I finished a zine about CSS, and also wrote another entire zine about bash while I was procrastinating on finishing the CSS zine in a self-imposed “write an entire zine in October” challenge, so you should see those here soon too. I’m pretty excited about both of them.