Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Daily blog posts about my time at RC

A quick note: I’ve been writing some daily-ish blog posts about what I’ve been doing in my time at the Recurse Center, but I took them out of this RSS feed because I think they’re a bit more stream of consciousness than my usual posts. Here’s where to find them if you’re interested:

- You can find them all in the Recurse Center 2020 category

- If you want to subscribe to my daily RC posts, here’s an RSS link

Docker Compose: a nice way to set up a dev environment

Hello! Here is another post about computer tools that I’ve appreciated. This one is about Docker Compose!

This post is mostly just about how delighted I was that it does what it’s supposed to do and it seems to work and to be pretty straightforward to use. I’m also only talking about using Docker Compose for a dev environment here, not using it in production.

I’ve been thinking about this kind of personal dev environment setup more recently because I now do all my computing with a personal cloud budget of like $20/month instead of spending my time at work thinking about how to manage thousands of AWS servers.

I’m very happy about this because previous to trying Docker Compose I spent two days getting frustrated with trying to set up a dev environment with other tools and Docker Compose was a lot easier and simpler. And then I told my sister about my docker-compose experiences and she was like “I KNOW, DOCKER COMPOSE IS GREAT RIGHT?!?!” So I thought I’d write a blog post about it, and here we are.

the problem: setting up a dev environment

Right now I’m working on a Ruby on Rails service (the backend for a sort of computer debugging game). On my production server, I have:

- a nginx proxy

- a Rails server

- a Go server (which proxies some SSH connections with gotty)

- a Postgres database

Setting up the Rails server locally was pretty straightforward without

resorting to containers (I just had to install Postgres and Ruby, fine, no big deal), but then

I wanted send /proxy/* to the Go server and everything else to the Rails

server, so I needed nginx too. And installing nginx on my laptop felt too messy

to me.

So enter docker-compose!

docker-compose lets you run a bunch of Docker containers

Docker Compose basically lets you run a bunch of Docker containers that can communicate with each other.

You configure all your containers in one file called docker-compose.yml. I’ve

pasted my entire docker-compose.yml file here for my server because I found

it to be really short and straightforward.

version: "3.3"

services:

db:

image: postgres

volumes:

- ./tmp/db:/var/lib/postgresql/data

environment:

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: password # yes I set the password to 'password'

go_server:

# todo: use a smaller image at some point, we don't need all of ubuntu to run a static go binary

image: ubuntu

command: /app/go_proxy/server

volumes:

- .:/app

rails_server:

build: docker/rails

command: bash -c "rm -f tmp/pids/server.pid && source secrets.sh && bundle exec rails s -p 3000 -b '0.0.0.0'"

volumes:

- .:/app

web:

build: docker/nginx

ports:

- "8777:80" # this exposes port 8777 on my laptop

There are two kinds of containers here: for some of them I’m just

using an existing image (image: postgres and image: ubuntu) without

modifying it at all. And for some I needed to build a custom container image –

build: docker/rails says to use docker/rails/Dockerfile to build a custom

container.

I needed to give my Rails server access to some API keys and things, so source secrets.sh puts a bunch of secrets in environment variables. Maybe there’s a

better way to manage secrets but it’s just me so this seemed fine.

how to start everything: docker-compose build then docker-compose up

I’ve been starting my containers just by running docker-compose build to

build the containers, then docker-compose up to run everything.

You can set depends_on in the yaml file to get a little more control over

when things start in, but for my set of services the start order

doesn’t matter, so I haven’t.

the networking is easy to use

It’s important here that the containers be able to connect to each other.

Docker Compose makes that super simple! If I have a Rails server running in my

rails_server container on port 3000, then I can access that with

http://rails_server:3000. So simple!

Here’s a snippet from my nginx configuration file with how I’m using that in

practice (I removed a bunch of proxy_set_header lines to make it more clear)

location ~ /proxy.* {

proxy_pass http://go_server:8080;

}

location @app {

proxy_pass http://rails_server:3000;

}

Or here’s a snippet from my Rails project’s database configuration, where I use the name of the database container (db):

development:

<<: *default

database: myproject_development

host: db # <-------- this "magically" resolves to the database container's IP address

username: postgres

password: password

I got a bit curious about how rails_server was actually getting resolved to

an IP address. It seems like Docker is running a DNS server somewhere on my

computer to resolve these names. Here are some DNS queries where we can see that each container has its own IP address:

$ dig +short @127.0.0.11 rails_server

172.18.0.2

$ dig +short @127.0.0.11 db

172.18.0.3

$ dig +short @127.0.0.11 web

172.18.0.4

$ dig +short @127.0.0.11 go_server

172.18.0.5

who’s running this DNS server?

I dug into how this DNS server is set up a very tiny bit.

I ran all these commands outside the container, because I didn’t have a lot of networking tools installed in the container.

step 1: find the PID of my Rails server with ps aux | grep puma

It’s 1837916. Cool.

step 2: find a UDP server running in the same network namespace as PID 1837916

I did this by using nsenter to run netstat in the same network namespace as

the puma process. (technically I guess you could run netstat -tupn to just

show UDP servers, but my fingers only know how to type netstat -tulpn at this

point)

$ sudo nsenter -n -t 1837916 netstat -tulpn

Active Internet connections (only servers)

Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address State PID/Program name

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.11:32847 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 1333/dockerd

tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:3000 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 1837916/puma 4.3.7

udp 0 0 127.0.0.11:59426 0.0.0.0:* 1333/dockerd

So there’s a UDP server running on port 59426, run by dockerd! Maybe that’s the DNS server?

step 3: check that it’s a DNS server

We can use dig to make a DNS query to it:

$ sudo nsenter -n -t 1837916 dig +short @127.0.0.11 59426 rails_server

172.18.0.2

But – when we ran dig earlier, we weren’t making a DNS query to port 59426,

we were querying port 53! What’s going on?

step 4: iptables

My first guess for “this server seems to be running on port X but I’m accessing it on port Y, what’s going on?” was “iptables”.

So I ran iptables-save in the container’s network namespace, and there we go:

$ sudo nsenter -n -t 1837916 iptables-save

.... redacted a bunch of output ....

-A DOCKER_POSTROUTING -s 127.0.0.11/32 -p udp -m udp --sport 59426 -j SNAT --to-source :53

COMMIT

There’s an iptables rule that sends traffic on port 53 to 59426. Fun!

it stores the database files in a temp directory

One nice thing about this is: instead of managing a Postgres installation on my

laptop, I can just mount the Postgres container’s data directory at ./tmp/db.

I like this because I really do not want to administer a Postgres installation on my laptop (I don’t really know how to configure Postgres), and conceptually I like having my dev database literally be in the same directory as the rest of my code.

I can access the Rails console with docker-compose exec rails_server rails console

Managing Ruby versions is always a little tricky and even when I have it working, I always kind of worry I’m going to screw up my Ruby installation and have to spend like ten years fixing it.

With this setup, if I need access to the Rails console (a REPL with all my Rails code loaded), I can just run:

$ docker-compose exec rails_server rails console

Running via Spring preloader in process 597

Loading development environment (Rails 6.0.3.4)

irb(main):001:0>

Nice!

small problem: no history in my Rails console

I ran into a problem though: I didn’t have any history in my Rails console anymore, because I was restarting the container all the time.

I figured out a pretty simple solution to this though: I added a

/root/.irbrc to my container that changed the IRB history file’s location to

be something that would persist between container restarts. It’s just one line:

IRB.conf[:HISTORY_FILE] = "/app/tmp/irb_history"

I still don’t know how well it works in production

Right now my production setup for this project is still “I made a digitalocean droplet and edited a lot of files by hand”.

I think I’ll try to use docker-compose to run this thing in production. My guess is that it should work fine because this service is probably going to have at most like 2 users at a time and I can easily afford to have 60 seconds of downtime during a deploy if I want, but usually something goes wrong that I haven’t thought of.

A few notes from folks on Twitter about docker-compose in production:

docker-compose upwill only restart the containers that need restarting, which makes restarts faster- there’s a small bash script wait-for-it that you can use to make a container wait for another service to be available

- You can have 2 docker-compose.yaml files:

docker-compose.yamlfor DEV, anddocker-compose-prod.yamlfor prod. I think I’ll use this to expose different nginx ports: 8999 in dev and 80 in prod. - folks seemed to agree that docker-compose is fine in production if you have a small website running on 1 computer

- one person suggested that Docker Swarm might be better for a slightly more complicated production setup, but I haven’t tried that (or of course Kubernetes, but the whole point of Docker Compose is that it’s super simple and Kubernetes is certainly not simple :) )

Docker also seems to have a feature to automatically deploy your docker-compose setup to ECS, which sounds cool in theory but I haven’t tried it.

when doesn’t docker-compose work well?

I’ve heard that docker-compose doesn’t work well:

- when you have a very large number of microservices (a simple setup is best)

- when you’re trying to include data from a very large database (like putting hundreds of gigabytes of data on everyone’s laptop)

- on Mac computers, I’ve heard that Docker can be a lot slower than on Linux (presumably because of the extra VM). I don’t have a Mac so I haven’t run into this.

that’s all!

I spent an entire day before this trying to configure a dev environment by using Puppet to provision a Vagrant virtual machine only to realize that VMs are kind of slow to start and that I don’t really like writing Puppet configuration (I know, huge surprise :)).

So it was nice to try Docker Compose and find that it was straightforward to get to work!

2020: Year in review

I write these every year, so here’s 2020! I’m not going to really go into the disaster that was 2020, I’m just going to talk about some things I worked on. So here are some things I did this year and a few reflections, as usual. I’m much more grateful than usual that my family and friends are generally healthy.

zines!

I published 4 zines:

This year definitely had an accidental “weird programming languages” theme (bash, CSS, and SQL) which I kind of love. I’m also really delighted I finally managed to publish that containers zine, because I’d wanted to write it for a long time and I’m really happy with how it turned out.

For two of these zines, I also made companion websites with examples:

- Become a SELECT Star: SQL playground

- Hell Yes! CSS!: CSS examples

Both of those sites are trying to get at a tension that I always feel with my zines which is – you can’t really learn about computers without trying things! So they both give you a way to quickly try things out and experiment.

I’m still honestly not sure how well these are working because I haven’t gotten a lot of feedback on them (positive or negative), but I still feel that this is important so I’m going to keep working on this.

a redesign of wizardzines.com

I redesigned https://wizardzines.com this year! As with any website redesign, I think this is like 50x more exciting to me than literally anyone else in the universe so I won’t say too much about it, but it has a fun animations, I think the information is a better organized, and I really love it.

You can see what it looked like before and after. Melody Starling did all the design and CSS work.

I basically wrote the CSS zine because we did this project and I was so amazed and delighted by what Melody could do with CSS that I had to write a zine about CSS.

I shipped some zines!

I wanted to print and ship some zines in 2020, and I did! I had kind of Grand Ambitions for this and in reality what happened was:

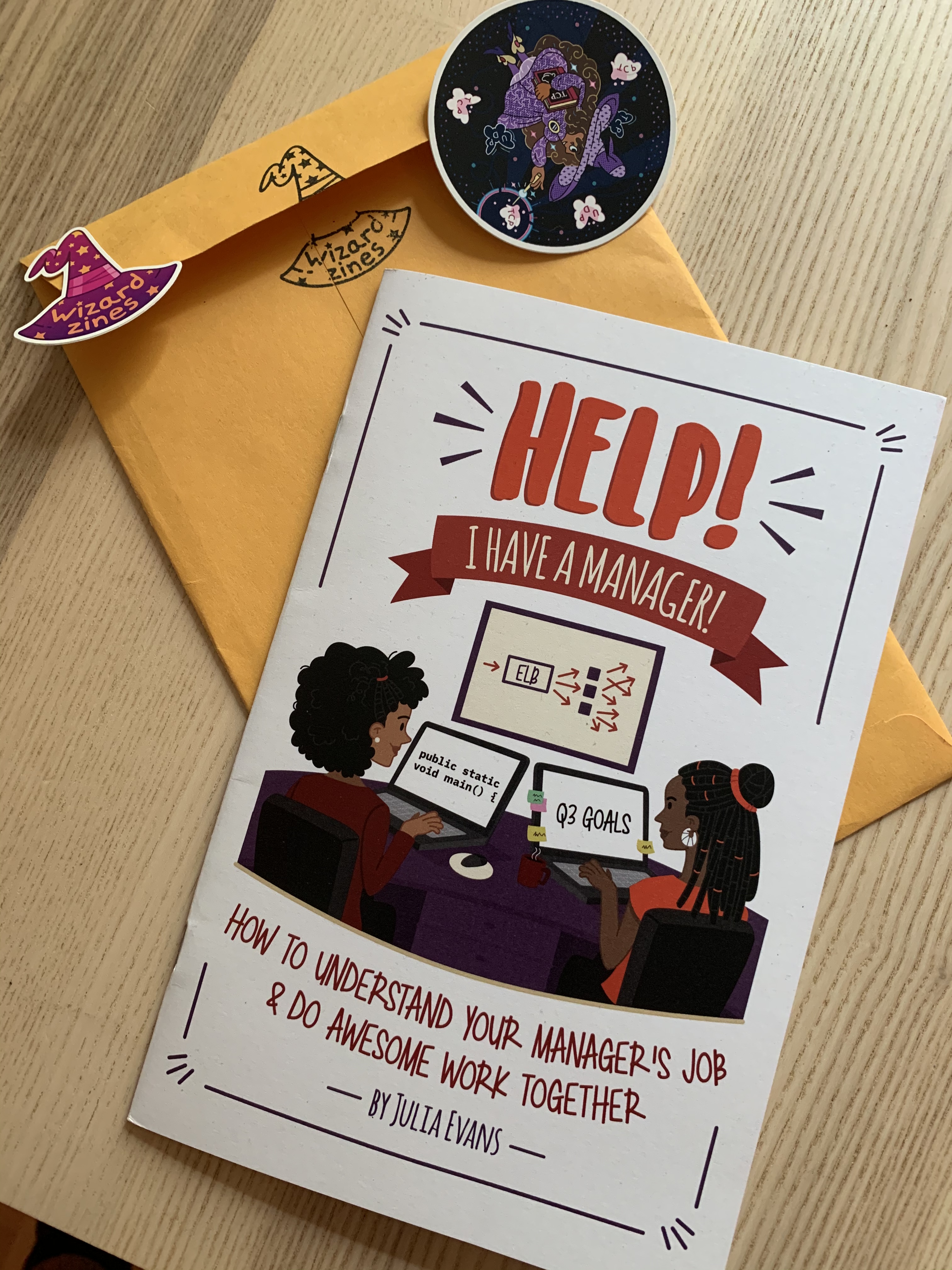

- I got 400 copies of “Help! I have a Manager!” printed in February

- there was a pandemic and I got distracted so I left them in a box in my house for 6 months

- I finally got around to announcing them in August and shipped the zines to people in September

I wanted the whole thing to feel special, so I designed & printed custom envelopes and got a local stamp maker to design a stamp to stamp the envelope seal with. Here’s what it looked like:

I got a lot of excited tweets from people receiving their zines, which was really nice.

The main problems I ran into were:

- shipping is a lot of work, it took me maybe 2-3 days to get all 400 zines packaged and shipped

- in order for me to charge a reasonable price ($16 USD/zine), I had to ship everything with letter mail, which mostly worked but some people didn’t get their zines or it took many weeks for the zines to arrive. And there was no tracking so it was hard/impossible for me to find out about problems.

I definitely want to ship more zines, but I think I might have to do it in a less fun and artisanal way. We’ll see!

learning experiment: questions

One of my experiments in helping pepole learn this year was a site called “questions!”, which you can try at https://questions.wizardzines.com/ (for example here are some questions about CORS.

The idea is that it asks you questions about a topic as a way for you to find out what you don’t know and learn something.

I spent a lot of time figuring out how to make this not feel like a quiz. The first version of this I built was called flashcards, and while people seemed to like those, I found that too many people were reacting to it with “I got 9⁄10!” as if the goal was to get as many questions right as possible.

To make it clearer that the point was to learn, we made the primary interaction on the site clicking on “I learned something!” (which triggers an animation and a lightbulb). So you don’t get rewarded for already knowing the thing, you get rewarded for learning something new.

I also published an open source version of the site, if you want to make your own: https://github.com/questions-template/questions-template.github.io. I’d be really interested to hear if anyone does.

Melody designed this site too.

I still feel a bit unsure about the future of this project, but I’m happy with where I got with it this year.

learning experiment: domain name saturday

With my friend Allison Kaptur, I ran an event called “Domain Name Saturday” at the Recurse Center where you write a DNS server in 1 day.

It turns out it’s impossible to write a DNS server in 1 day (literally nobody succeeded, but I think it might be possible in 2 days). But it was a really fun exercise and a lot of people made very significant progress. At the end we did a “bug presentations” event where people presented their favourite bug they ran into while writing their DNS server. I really liked this structure because it’s easy for everyone to participate no matter how far they got (everyone has bugs!), and people’s bugs were really interesting!

I think it’s a super fun exercise for learning about networking and parsing binary data and I’m excited to try to run it again someday.

we ran !!Con remotely!

!!Con West was the last thing I did before the pandemic, back on March 1 in the very last days of in-person conferences.

We ran !!Con NYC remotely this year (you can watch the recordings!). It was a delightful bright spot this year. I think it really worked well as a remote conference because !!Con (unlike a lot of conferences) really is largely about the talks and about the joy of watching a lot of delightful talks together.

I think we managed to reproduce the experience of sitting in a big room and clapping and being excited about a fun shared experience pretty well (through discord and a lot of clapping emojis). It was definitely much harder to actually talk to individual people.

We charged $64 for tickets (pay-what-you-can), which included a conference tshirt mailed to your house in the ticket price. So I wrote a Python script to mail a few hundred conferences tshirts / sweaters to people with Printful. It was fun but next time I’d probably just make a Shopify/Squarespace store and give everyone a code to order a free shirt though, it involved a little too much customer support caused by bugs in my script :)

running a business is going well!

Last year at this time, I said I was going to take until August 2020 and reevaluate how I felt about this whole “running a business” thing. When August came around I felt like I was generally having fun and the business is doing well. So “reevaluate how I felt” turned into “shrug and keep doing what I’m doing”.

Revenue is up 2.3x over last year, which is incredible and probably very related to the fact that I published twice as many zines.

I continue to enjoy being able to easily understand what value the work I’m doing brings to the world and having a lot of control over my time. I still miss having coworkers though :)

what went well

- working with other people. I’m not going to list everyone here but I wrote a personal 2020 retro and a lot of my high points were like “I got to work with X person and it was SO GREAT and I couldn’t have done any of these things without them”

- beta readers. I started asking beta readers to read my zines and tell me which parts are confusing and it was AMAZING. If you were one of these 50-ish people, thank you so much!

- new tools. I started using Trello to track what needs to be done for my zines instead of literally no organizational system at all and it really helped a lot. I also started using focusmate to, well, focus, and that helped a lot too. I wrote probably 80% of the bash zine in Focusmate sessions and it was a lot faster and less stressful.

- royalties. I got to pay out more royalties this year and that was really cool.

- I kept learning about running a business and wrote my first blog post about what I’ve learned: A few things I’ve learned about email marketing. I don’t want to get too much into giving business advice, but I think I want to write a couple more posts about what I’ve learned next year.

some questions about 2021

I don’t think anyone can answer these except me, but here are a few work things that are on my mind:

- For some reason I feel compelled to make more educational things that aren’t zines, like these little websites I talked about earlier that ask you questions or let you run SQL queries / try out CSS ideas. I have another project that I’ve started here that I’ll write about later.

- I’m not sure what I’m going to do about printing/shipping, I really liked the artisanal way I did it this year, but it was a lot of work.

- As always, I have very few ideas about what I’m going to write a zine about next. It’s always like this but it always feels hard to come up with ideas. I do have 1 idea for my next zine though which is a lot more than usual! Maybe it’ll work out!

here’s to 2021 being a better year

Stay safe everyone. Happy new year.

How I write useful programming comics

How I write useful programming comics

The other day a friend was asking me how I write programming comics. I’ve tried to write about this at least 6 times (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6), but I felt like there’s still something missing so here’s another attempt.

drawing isn’t the hard part

The 2 common questions/comments I get about my comics are:

- “what tools do you use?” (an ipad + apple pencil + a drawing app).

- I wish I were good at drawing so that I could do that

But neither of these is what I actually find hard about comics: I’m actually very bad at drawing, and I’ve made comics that people love with very simple tools, like taking a low-quality picture of a notebook with my phone.

So what’s the secret?

3 types of comics I draw

I think a lot of my comics fall into 3 categories. I don’t think that this categorization is totally accurate, but I think it’s a helpful way to start talking about how to do it.

Type 1: the Surprising/Hidden Fact

Here are 10 examples of surprising ideas I’ve written about:

- SELECT queries aren’t executed in the order they’re written in

- position: absolute isn’t absolute

- cookies let a server store information in your browser

- the /proc directory on linux lets you access information about processes

- linux uses copy on write for a new process’s memory

- ngrep is like ‘grep’ for network packets

- a git branch is a pointer to a commit

- if you ask about specific things you want feedback on, you’re more likely to get the feedback you need

- container layers are implemented using overlay filesystems

Of course, a lot of these aren’t that surprising when you already know about them – “cookies let a server store information in your browser” is a basic fact about how cookies work! But if you don’t already know it, it’s pretty surprising and kind of exciting to learn.

I think there are at least two subtypes of surprising facts here:

- Facts that tell you about something you can do (like “use ngrep to grep your network packets”)

- Facts that explain why something works the way it does (“oh, I’m always confused about SQL queries because they’re not executed in the order they’re written in! That explains a lot!”)

Type 2: the List of Important Things about X

This sounds pretty boring at first (“uh, a list?”), but most of the comics I’ve drawn where people tell me “This is amazing, I printed this out and put it on my wall” are lists. Here are some examples of list comics:

- every linux networking tool I know

- what to talk about in 1:1s with your manager

- the most important HTTP request headers

- HTTP status codes

- ways I want my team to be

- grep’s command line arguments

- find’s command line arguments

- dig’s command line arguments

- about 30 other “X’s most important command line arguments and what they do” (basically all of bite size command line and bite size networking)

A key things about this is that it’s not just “a list of facts about X” (anyone can make a list!) but a list of the most important facts about X. For example, grep has a lot of command line arguments. But it turns out that I only ever use 9 of them even though I use a grep a LOT, and that each of those 9 options can be explained in just a few words.

All of the topics are super specific, like “HTTP request headers”, “HTTP response headers”, and “topics for 1:1s”.

Type 3: the Relatable Story

The last type (and the type I’m the least certain how to categorize) is sort of a story that resonates with people. I think that this one is really important but I can’t do it justice right now so I’m going to stick to talking about the other two types in this post.

- take on hard projects

- how I got better at debugging

- how to be a wizard programmer

- data analysis is always more work than I think

source 1 of Surprising Facts: things I learned somewhat recently

Okay, so how do you find surprising facts to share? The way I started out was to just share things I learned that I was surprised by!

I started doing this on my blog, not in comics: I’d learn something that I was surprised by, and think “oh, this is cool, I should write a blog post about it so other people can learn it too!“. And then I’d write it up and often people would be really happy to learn the thing too!

Obviously I don’t think everyone needs to have a tech blog, but I do think that noticing surprising computer facts as you learn them and explaining them clearly is a skill that you need to practice if you want to get good at it!

source 2 of Surprising Facts: things other people find surprising

Recently I’ve moved a little more into what I feel is the Hard Mode of surprising facts – things that I have not been personally surprised by recently, but that a lot of people who don’t know about the topic yet would be really surprised by.

I think the main way to discover Surprising Facts like this is by talking to people who do not know the thing already and observing what they find surprising. For example I might have an interaction like this:

- me (showing someone to a coworker) so you can do TASK like this…

- coworker: um wait you can do that?? That’s so cool! I have a lot of questions!

- me: oh yeah it’s so useful!

For me, HTTP cookies were an example this – I’d forgotten that it could be surprising / interesting to learn how they worked because I learned about them a while ago, and then one day a friend asked me “hey, how do cookies work?”. And I remembered that it’s really cool and useful to know, so I wrote it down!

Another example of this is SELECT queries start with FROM – this was something that I understood intuitively and hadn’t thought about. But when walking through a SQL query’s execution with someone, I noticed that they were really surprised that you didn’t execute the query in the same order that it was written. And I realized “oh yeah, that IS weird actually, I bet a lot of other people are confused by that too!“. So I wrote it down and it helped a lot of people!

I think the skill of “figuring out what people typically find surprising when learning a topic and coming up with clear explanations” is probably called “teaching”.

Lists of Important Things are a little bit easier to write

I find writing lists a little easier than writing Surprising Facts – it’s hard to come up with a useful topic for a list, but once I have the topic (like “every linux networking tool I know”), it feels somewhat straightforward to list them all and briefly explain the basics of each one.

I only write comics about things I know relatively well

People also ask me pretty often if I write comics about topics I’m learning as I learn them. I don’t do this basically because I find writing short things a LOT harder than writing long things.

I do write blog posts about topics I’m just learning – if there’s a topic I’m still not super clear on, I can usually write a 1200-word blog post about it with some basic facts and questions and examples. But if I’m still a little bit confused about the topic, it’s very hard to definitively list “Here are the 3 most important surprising facts you need to know to understand TOPIC”, because very likely I actually don’t know those 3 facts yet! Or maybe I kind of know them, they’re mixed in with a lot of other things that I’m not sure about and aren’t as important.

that’s all for now!

Hopefully this is helpful! Someone pointed out that this advice might also apply to blog posts, which, maybe it does!

An attempt at implementing char-rnn with PyTorch

Hello! I spent a bunch of time in the last couple of weeks implementing a version of char-rnn with PyTorch. I’d never trained a neural network before so this seemed like a fun way to start.

The idea here (from The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Recurrent Neural Networks) is that you can train a character-based recurrent neural network on some text and get surprisingly good results.

I didn’t quite get the results I was hoping for, but I wanted to share some example code & results in case it’s useful to anyone else getting started with PyTorch and RNNs.

Here’s the Jupyter notebook with the code: char-rnn in PyTorch.ipynb. If you click “Open in Colab” at the top, you can open it in Google’s Colab service where at least right now you can get a free GPU to do training on. The whole thing is maybe 75 lines of code, which I’ll attempt to somewhat explain in this blog post.

step 1: prepare the data

First up: we download the data! I used Hans Christian Anderson’s fairy tales from Project Gutenberg.

!wget -O fairy-tales.txt

Here’s the code to prepare the data. I’m using the Vocab class from fastai,

which can turn a bunch of letters into a “vocabulary” and then use that

vocabulary to turn letters into numbers.

Then we’re left with a big array of numbers (training_set) that we can use to

train a model.

from fastai.text import *

text = unidecode.unidecode(open('fairy-tales.txt').read())

v = Vocab.create((x for x in text), max_vocab=400, min_freq=1)

training_set = torch.Tensor(v.numericalize([x for x in text])).type(torch.LongTensor).cuda()

num_letters = len(v.itos)

step 2: define a model

This is a wrapper around PyTorch’s LSTM class. It does 3 main things in addition to just wrapping the LSTM class:

- one hot encode the input vectors, so that they’re the right dimension

- add another linear transformation after the LSTM, because the LSTM outputs a

vector with size

hidden_size, and we need a vector that has sizeinput_sizeso that we can turn it into a character - Save the LSTM hidden vector (which is actually 2 vectors) as an instance

variable and run

.detach()on it after every round. (I struggle to articulate what.detach()does, but my understanding is that it kind of “ends” the calculation of the derivative of the model)

class MyLSTM(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, input_size, hidden_size):

super().__init__()

self.lstm = nn.LSTM(input_size, hidden_size, batch_first=True)

self.h2o = nn.Linear(hidden_size, input_size)

self.input_size=input_size

self.hidden = None

def forward(self, input):

input = torch.nn.functional.one_hot(input, num_classes=self.input_size).type(torch.FloatTensor).cuda().unsqueeze(0)

if self.hidden is None:

l_output, self.hidden = self.lstm(input)

else:

l_output, self.hidden = self.lstm(input, self.hidden)

self.hidden = (self.hidden[0].detach(), self.hidden[1].detach())

return self.h2o(l_output)

This code also does something kind of magical that isn’t obvious at all – if you pass it

in a vector of inputs (like [1,2,3,4,5,6]), corresponding to 6 letters, my

understanding is that nn.LSTM will internally update the hidden vector 6

times using backpropagation through time.

step 3: write some training code

This model won’t just train itself!

I started out trying to use a training helper class from the fastai library (which

is a wrapper around PyTorch). I found that kind of confusing because I didn’t

understand what it was doing, so I ended up writing my own training code.

Here’s some code to show basically what 1 round of training looks like (the

epoch() method). Basically what this is doing is repeatedly:

- Give the RNN a string like

and they ought not to teas(as a vector of numbers, of course) - Get the prediction for the next letter

- Compute the loss between what the RNN predicted, and the real next letter

(

e, because tease ends ine) - Calculate the gradient (

loss.backward()) - Change the weights in the model in the direction of the gradient (

self.optimizer.step())

class Trainer():

def __init__(self):

self.rnn = MyLSTM(input_size, hidden_size).cuda()

self.optimizer = torch.optim.Adam(self.rnn.parameters(), amsgrad=True, lr=lr)

def epoch(self):

i = 0

while i < len(training_set) - 40:

seq_len = random.randint(10, 40)

input, target = training_set[i:i+seq_len],training_set[i+1:i+1+seq_len]

i += seq_len

# forward pass

output = self.rnn(input)

loss = F.cross_entropy(output.squeeze()[-1:], target[-1:])

# compute gradients and take optimizer step

self.optimizer.zero_grad()

loss.backward()

self.optimizer.step()

let nn.LSTM do backpropagation through time, don’t do it myself

Originally I wrote my own code to pass in 1 letter at a time to the LSTM and then periodically compute the derivative, kind of like this:

for i in range(20):

input, target = next(iter)

output, hidden = self.lstm(input, hidden)

loss = F.cross_entropy(output, target)

hidden = hidden.detach()

self.optimizer.zero_grad()

loss.backward()

self.optimizer.step()

This passes in 20 letters (one at a time), and then takes a training step at the end. This is called backpropagation through time and Karpathy mentions using this method in his blog post.

This kind of worked, but my loss would go down for a while and then kind of

spike later in training. I still don’t understand why this happened, but when I

switched to instead just passing in 20 characters at a time to the LSTM (as the

seq_len dimension) and letting it do the backpropagation itself, things got a

lot better.

step 4: train the model!

I reran this training code over the same data maybe 300 times, until I got bored and it started outputting text that looked vaguely like English. This took about an hour or so.

In this case I didn’t really care too much about overfitting, but if you were doing this for a Real Reason it would be good to run it on a validation set.

step 5: generate some output!

The last thing we need to do is to generate some output from the model! I wrote

some helper methods to generate text from the model (make_preds and

next_pred). It’s mostly just trying to get the dimensions of things right,

but here’s the main important bit:

output = rnn(input)

prediction_vector = F.softmax(output/temperature)

letter = v.textify(torch.multinomial(prediction_vector, 1).flatten(), sep='').replace('_', ' ')

Basically what’s going on here is that

- the RNN outputs a vector of numbers (

output), one for each letter/punctuation in our alphabet. - The

outputvector isn’t yet a vector of probabilities, soF.softmax(output/temperature)turns it into a bunch of probabilities (aka “numbers that add up to 1”).temperaturekind of controls how much to weight higher probabilities – in the limit if you set temperature=0.0000001, it’ll always pick the letter with the highest probability. torch.multinomial(prediction_vector)takes the vector of probabilities and uses those probabilites to pick an index in the vector (like 12)v.textifyturns “12” into a letter

If we want 300 characters worth of text, we just repeat this process 300 times.

the results!

Here’s some generated output from the model where I set temperature = 1 in

the prediction function. It’s kind of like English, which is pretty impressive

given that this model needed to “learn” English from scratch and is totally

based on character sequences.

It doesn’t make any sense, but what did we expect really.

“An who was you colotal said that have to have been a little crimantable and beamed home the beetle. “I shall be in the head of the green for the sound of the wood. The pastor. “I child hand through the emperor’s sorthes, where the mother was a great deal down the conscious, which are all the gleam of the wood they saw the last great of the emperor’s forments, the house of a large gone there was nothing of the wonded the sound of which she saw in the converse of the beetle. “I shall know happy to him. This stories herself and the sound of the young mons feathery in the green safe.”

“That was the pastor. The some and hand on the water sound of the beauty be and home to have been consider and tree and the face. The some to the froghesses and stringing to the sea, and the yellow was too intention, he was not a warm to the pastor. The pastor which are the faten to go and the world from the bell, why really the laborer’s back of most handsome that she was a caperven and the confectioned and thoughts were seated to have great made

Here’s some more generated output at temperature=0.1, which weights its

character choices closer to “just pick the highest probability character every

time”. This makes the output a lot more repetitive:

ole the sound of the beauty of the beetle. “She was a great emperor of the sea, and the sun was so warm to the confectioned the beetle. “I shall be so many for the beetle. “I shall be so many for the beetle. “I shall be so standen for the world, and the sun was so warm to the sea, and the sun was so warm to the sea, and the sound of the world from the bell, where the beetle was the sea, and the sound of the world from the bell, where the beetle was the sea, and the sound of the wood flowers and the sound of the wood, and the sound of the world from the bell, where the world from the wood, and the sound of the

It’s weirdly obsessed with beetles and confectioners, and the sun, and the sea. Seems fine!

that’s all!

my results are nowhere near as good as Karpathy’s so far, maybe due to one of the following:

- not enough training data

- I got bored with training after an hour and didn’t have the patience to babysit the Colab notebook for longer

- he used a 2-layer LSTM with more hidden parameters than me, I have 1 layer

- something else entirely

But I got some vaguely coherent results! Hooray!