Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Get better at programming by learning how things work

When we talk about getting better at programming, we often talk about testing, writing reusable code, design patterns, and readability.

All of those things are important. But in this blog post, I want to talk about a different way to get better at programming: learning how the systems you’re using work! This is the main way I approach getting better at programming.

examples of “how things work”

To explain what I mean by “how things work”, here are some different types of programming and examples of what you could learn about how they work.

Frontend JS:

- how the event loop works

- HTTP methods like GET and POST

- what the DOM is and what you can do with it

- the same-origin policy and CORS

CSS:

- how inline elements are rendered differently from block elements

- what the “default flow” is

- how flexbox works

- how CSS decides which selector to apply to which element (the “cascading” part of the cascading style sheets)

Systems programming:

- the difference between the stack and the heap

- how virtual memory works

- how numbers are represented in binary

- what a symbol table is

- how code from external libraries gets loaded (e.g. dynamic/static linking)

- Atomic instructions and how they’re different from mutexes

you can use something without understanding how it works (and that can be ok!)

We work with a LOT of different systems, and it’s unreasonable to expect that every single person understands everything about all of them. For example, many people write programs that send email, and most of those people probably don’t understand everything about how email works. Email is really complicated! That’s why we have abstractions.

But if you’re working with something (like CSS, or HTTP, or goroutines, or email) more seriously and you don’t really understand how it works, sometimes you’ll start to run into problems.

your bugs will tell you when you need to improve your mental model

When I’m programming and I’m missing a key concept about how something works, it doesn’t always show up in an obvious way. What will happen is:

- I’ll have bugs in my programs because of an incorrect mental model

- I’ll struggle to fix those bugs quickly and I won’t be able to find the right questions to ask to diagnose them

- I feel really frustrated

I think it’s actually an important skill just to be able to recognize that this is happening: I’ve slowly learned to recognize the feeling of “wait, I’m really confused, I think there’s something I don’t understand about how this system works, what is it?”

Being a senior developer is less about knowing absolutely everything and more about quickly being able to recognize when you don’t know something and learn it. Speaking of being a senior developer…

even senior developers need to learn how their systems work

So far I’ve never stopped learning how things work, because there are so many different types of systems we work with!

For example, I know a lot of the fundamentals of how C programs work and web programming (like the examples at the top of this post), but when it comes to graphics programming/OpenGL/GPUs, I know very few of the fundamental ideas. And sometimes I’ll discover a new fact that I’m missing about a system I thought I knew, like last year I discovered that I was missing a LOT of information about how CSS works.

It can feel bad to realise that you really don’t understand how a system you’ve been using works when you have 10 years of experience (“ugh, shouldn’t I know this already? I’ve been using this for so long!“), but it’s normal! There’s a lot to know about computers and we are constantly inventing new things to know, so nobody can keep up with every single thing.

how I go from “I’m confused” to “ok, I get it!”

When I notice I’m confused, I like to approach it like this:

- Notice I’m confused about a topic (“hey, when I write

awaitin my Javascript program, what is actually happening?“) - Break down my confusion into specific factual questions, like “when there’s

an

awaitand it’s waiting, how does it decide which part of my code runs next? Where is that information stored?” - Find out the answers to those questions (by writing a program, reading something on the internet, or asking someone)

- Test my understanding by writing a program (“hey, that’s why I was having that async bug! And I can fix it like this!“)

The last “test my understanding” step is really important. The whole point of understanding how computers work is to actually write code to make them do things!

I find that if I can use my newfound understanding to do something concrete like implement a new feature or fix a bug or even just write a test program that demonstrates how the thing works, it feels a LOT more real than if I just read about it. And then it’s much more likely that I’ll be able to use it in practice later.

just learning a few facts can help a lot

Learning how things work doesn’t need to be a big huge thing. For example, I used to not really know how floating point numbers worked, and I felt nervous that something weird would happen that I didn’t understand.

And then one day in 2013 I went to a talk by Stefan Karpinski explaining how floating point numbers worked (containing roughly the information in this comic, but with more weird details). And now I feel totally confident using floating point numbers! I know what their basic limitations are, and when not to use them (to represent integers larger than 2^53). And I know what I don’t know – I know it’s hard to write numerically stable linear algebra algorithms and I have no idea how to do that.

connect new facts to information you already know

When learning a new fact, it’s easy to be able to recite a sentence like “ok, there are 8 bits in a byte”. That’s true, but so what? What’s harder (and much more useful!) is to be able to connect that information to what you already know about programming.

For example, let’s take this “8 bits in a byte thing”. In your program you probably have strings, like “Hello”. You can already start asking lots of questions about this, like:

- How many bytes in memory are used to represent the string “Hello”? (it’s 6 – 5 characters plus a null byte at the end)

- What bits exactly does the letter “H” correspond to? (the encoding for “Hello” is going to be using ASCII, so you can look it up in an ASCII table!)

- If you have a running program that’s printing out the string “Hello”, can you go look at its memory and find out where those bytes are in its memory? How do you do that?

The important thing here is to ask the questions and explore the connections that you’re curious about – maybe you’re not so interested in how the strings are represented in memory, but you really want to know how many bytes a heart emoji is in Unicode! Or maybe you want to learn about how floating point numbers work!

I find that when I connect new facts to things I’m already familiar with (like emoji or floating point numbers or strings), then the information sticks a lot better.

Next up, I want to talk about 2 ways to get information: asking a person yes/no questions, and asking the computer.

how to get information: ask yes/no questions

When I’m talking to someone who knows more about the concept than me, I find it helps to start by asking really simple questions, where the answer is just “yes” or “no”. I’ve written about yes/no questions before in how to ask good questions, but I love it a lot so let’s talk about it again!

I do this because it forces me to articulate exactly what my current mental model is, and because I think yes/no questions are often easier for the person I’m asking to answer.

For example, here are some different types of questions:

- Check if your current understanding is correct

- Example: “Is a pixel shader the same thing as a fragment shader?”

- How concepts you’ve heard of are related to each other

- Example: “Does shadertoy use OpenGL?”

- Example: “Do graphics cards know about triangles?”

- High-level questions about what the main purpose of something is

- Example: “Does mysql orchestrator proxy database queries?”

- Example: “Does OpenGL give you more control or less control over the graphics card than Vulkan?”

yes/no questions put you in control

When I ask very open-ended questions like “how does X work?”, I find that it often goes wrong in one of 2 ways:

- The person starts telling me a bunch of things that I already knew

- The person starts telling me a bunch of things that I don’t know, but which aren’t really what I was interested in understanding

Both of these are frustrating, but of course neither of these things are their fault! They can’t know exactly what information I wanted about X, because I didn’t tell them. But it still always feels bad to have to interrupt someone with “oh no, sorry, that’s not what I wanted to know at all!”

I love yes/no questions because, even though they’re harder to formulate, I’m WAY more likely to get the exact answers I want and less likely to waste the time of the person I’m asking by having them explain a bunch of things that I’m not interested in.

asking yes/no questions isn’t always easy

When I’m asking someone questions to try to learn about something new, sometimes this happens:

me: so, just to check my understanding, it works like this, right?

them: actually, no, it’s <completely different thing>

me (internally): (brief moment of panic)

me: ok, let me think for a minute about my next question

It never quite feels good to learn that my mental model was totally wrong, even though it’s incredibly helpful information. Asking this kind of really specific question (even though it’s more effective!) puts you in a more vulnerable position than asking a broader question, because sometimes you have to reveal specific things that you were totally wrong about!

When this happens, I like to just say that I’m going to take a minute to incorporate the new fact into my mental model and think about my next question.

Okay, that’s the end of this digression into my love for yes/no questions :)

how to get information: ask the computer

Sometimes when I’m trying to answer a question I have, there won’t be anybody to ask, and I’ll Google it or search the documentation and won’t find anything.

But the delightful thing about computers is that you can often get answers to questions about computers by… asking your computer!

Here are a few examples (from past blog posts) of questions I’ve had and computer experiments I ran to answer them for myself:

- Are atomics faster or slower than mutexes? (blog post: trying out mutexes and atomics)

- If I add a user to a group, will existing processes running as that user have the new group? (blog post: How do groups work on Linux?)

- On Linux, if you have a server listening on 0.0.0.0 but you don’t have any network interfaces, can you connect to that server? (blog post: what’s a network interface?)

- How is the data in a SQLite database actually organized on disk? (blog post: How does SQLite work? Part 1: pages!)

asking the computer is a skill

It definitely takes time to learn how to turn “I’m confused about X” into specific questions, and then to turn that question into an experiment you can run on your computer to definitively answer it.

But it’s a really powerful tool to have! If you’re not limited to just the things that you can Google / what’s in the documentation / what the people around you know, then you can do a LOT more.

be aware of what you still don’t understand

Like I said earlier, the point here isn’t to understand every single thing. But especially as you get more senior, it’s important to be aware of what you don’t know! For example, here are five things I don’t know (out of a VERY large list):

- How database transactions / isolation levels work

- How vertex shaders work (in graphics)

- How font rendering works

- How BGP / peering work

- How multiple inheritance works in Python

And I don’t really need to know how those things work right now! But one day I’m pretty sure I’m going to need to know how database transactions work, and I know it’s something I can learn when that day comes :)

Someone who read this post asked me “how do you figure out what you don’t know?” and I didn’t have a good answer, so I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Thanks to Haider Al-Mosawi, Ivan Savov, Jake Donham, John Hergenroeder, Kamal Marhubi, Matthew Parker, Matthieu Cneude, Ori Bernstein, Peter Lyons, Sebastian Gutierrez, Shae Matijs Erisson, Vaibhav Sagar, and Zell Liew for reading a draft of this.

Things your manager might not know

When people talk about “managing up”, sometimes it’s framed as a bad thing – massaging the ego of people in charge so that they treat you well.

In my experience, managing up is usually a lot more practical. Your manager doesn’t (and can’t!) know every single detail about what you do in your job, and being aware of what they might not know and giving them the information they need to do their job well makes everyone’s job a lot easier.

Here are the facts your manager might not know about you and your team that we’ll cover in this post:

- What’s slowing the team down

- Exactly what individual people on the team are working on

- Where the technical debt is

- How to help you get better at your job

- What your goals are

- What issues they should be escalating

- What extra work you’re doing

- How compensation/promotions work at the company

For each one, I’ll give specific ways you can help get them the information they need. All of these ways you can help them will also help you – it’s not just an altruistic endeavor :)

This post (like all my writing about working with a manager) assumes that you generally have a good relationship with your manager.

your manager can’t know every detail about your job

I said this already, but I want to reiterate it: the reason your manager doesn’t know all these things isn’t because they’re not doing their job. It’s literally impossible for them to keep track of every detail about every person’s on their team’s job. It’s normal for managers to rely on their team to keep them informed about important facts they need to know, especially with more senior engineers.

Keeping them informed helps them do their job better, and it makes your job a lot easier too. Let’s talk about how that works!

they might not know: what’s slowing the team down

Sometimes, you’re working on a project and the project is going more slowly than you hoped. There are always reasons for this – maybe there have been a lot more bugs than you expected, maybe you’re using a new technology nobody on the team has ever used before, maybe you’re waiting for another team to do something. The reasons things are hard change a lot! Even if your manager knew what was slowing you down 2 weeks ago, maybe that issue has been totally resolved and you’re onto a totally different problem.

It’s a problem if your manager doesn’t know this mostly because if they know why you’re stuck, they might be able to help.

what you can do to help: tell them what’s hard about your job

It can feel bad to admit that you’re having trouble with something, but tasks usually aren’t hard because you’re “slow” or “bad at your job”. Usually it’s because there’s something concrete that’s making it hard. Identifying what that thing is and telling your manager about it helps them a lot!

For example, maybe you’re working on a feature and it’s turning out to be MUCH more complicated than you expected because there are a lot of edge cases that nobody had thought about. It’s useful for your manager to know that because sometimes they can help address it! They might:

- Encourage you to take the time you need to figure it out (“it’s really important to get all these edge cases right, I’m happy you’re doing this!”)

- Suggest someone who could help you (“Ankita was dealing with those exact issues last year, you should talk to her!”)

- Factor it into their planning (“Sounds like that won’t get done this week then, good to know”)

- Deprioritize the feature (“Oh, I thought this was going to be a quick fix, if this is really complicated we should focus our energy on something else instead”)

they might not know: exactly what individual people on the team are working on

Your manager almost certainly knows what the team as a whole is working on (maybe you’re working on releasing some new site), but do they know that today you’re working on getting a TLS certificate issued for the site and learning how CAs work? Maybe not!

The reason this is a problem for them is that someone might ask them “hey Manager, did your team get that TLS certificate yet?”, and it looks bad for them to not know the answer, or not be able to easily find out.

what you can do to help: keep them informed about your progress

You can ask your manager how they like to stay updated about what the team is doing: maybe they want to track everything through the issue tracker, maybe they want folks to write weekly digest, or maybe they have a different system.

If your team uses an issue tracker, taking a few minutes to keep it up to date can really help your manager keep a handle on what’s going on! If they can quickly look at the TLS ticket and see that you’re still working on it, that saves them a lot of time and means that you can spend your 1:1s discussing more important and interesting things than “hey, are you done with that TLS ticket?”.

they might not know: where the technical debt is

Your manager probably broadly understands what technology your team is using. But, especially if they’ve never worked as a software engineer on your specific team, they probably don’t know that much about the details! They may not completely understand the problems you’re having with your current architecture, or which systems are going to fail soon. They rely on you for that.

And it’s important for them to know about things like technical debt: if you have a system that isn’t going to meet your current scaling needs soon and is going to need a lot of work, that needs to get factored into planning!

what you can do to help: tell them about technical risks!

A couple of examples of things you can tell them about:

- technical debt that’s slowing you down when building new features

- systems that are causing a lot of disruption because they’re unreliable

they might not know: how to help you get better at your job

When I started out, I often felt like there were things I could be doing differently to do my job better. And that was definitely true! So I was sometimes confused about why my manager wasn’t giving me feedback about how I could be doing things better.

The reality is that in most cases, you probably know how to do your job better than your manager does! You’ve spent a lot more time thinking about the projects you’re working on, and they definitely can’t just parachute in and tell you how to improve. Of course, there are lots of times when your manager does have useful advice for you, but it’s not easy for them to figure out how to give it to you! Here are a few reasons why:

- They don’t necessarily even know what you’re struggling with in the first place (like we talked about in the last article)

- Even if they do know, it might not be obvious to them what they can do to improve the situation. Some managers are of course better at figuring this out than others – it’s not easy!

what you can do to help: identify what you need and ask for it!

Managers often LOVE it when you ask them for something that they can do that will help you. Here are a few examples of things you could ask for:

- less work: maybe you’re doing 3 projects and it’s too much and it’s making all of 3 projects go slowly, and you need to only be working on 2 things.

- harder work: maybe you don’t feel like you’re learning anything with your current work and you want to work on something that’s more of a challenge

- a learning budget: you’re learning about some new technology, and you think going to a conference will really help you, and you want a couple of days off and the budget to buy a ticket.

- help with an interpersonal situation: maybe you’re having a little bit of trouble working with someone else on the team, and you need some advice to understand what’s going on with that person and how to work with them more effectively.

- specific feedback on work you did: asking for feedback on a specific piece of work you did (“hey, do you have any feedback on that migration we did?“) is MUCH more effective than just asking “do you have any feedback for me?”.

Learning how to do this well takes a lot of practice – if you want to improve something about your job, it can be hard to break that down into “ok, the problem is X” and it’s even harder to identify something specific somebody else could do to address the problem. But if you can do it it’s WAY easier to get what you want and good managers will be delighted to help you!

It’s also definitely okay to bring up problems when you don’t specifically know what you need – if you’re not sure how to solve the problem you can explore possible solutions together!

more you can do to help: tell them your goals!

“Get better at your job” also means different things to different people. So if you have a specific career goal, it’s important to tell it to your manager! For example if you want to become an architect / team lead / manager one day, tell them that! Ask them what skills they think you’ll need to build to get there! Good managers will be delighted to talk to you about this, figure out what you need to do, and sponsor your work to help you get opportunities.

they might not know: what issues they should be escalating

Sometimes issues come up on the team that should actually be dealt with by someone higher up and that you can’t easily fix on your own. A few examples:

- You’re in a negotiation with a vendor and it’s not going well (vendor negotiations happen infrequently and they can be really tricky to handle for anyone!)

- You’re stuck because of a conflict in priorities between teams (your team needs another team to be doing X, but the other team thinks that the priority is Y).

It’s bad to try to handle issues you don’t have the power to fix on your own because it’ll take forever, it’ll be frustrating for you, and you won’t be able to make progress.

what you can do: practice escalating issues!

It’s usually not totally clear which things are part of your job and which things you should be escalating to your manager. The best way to get better at identifying what should be escalated is to ask your manager about it when you notice an issue you’re really struggling with! Eventually you’ll learn what kinds of issues should be escalated and which ones you should tackle on your own.

Identifying which things you should be escalating to your manager (“hey, I think you should know about this…”) isn’t easy, but it’s really a win/win when you can do it – if you escalate it to them, you’re no longer stuck trying to deal with an issue that’s impossible for you to fix, and they can make sure it gets done by people who actually have the power to do it.

they might not know: what extra work you’re doing

If you’re doing a bunch of extra work outside your normal job description, your manager might not realize that! It’s important to bring it up with your manager so that they can give you credit for that work (put it in your brag document!).

Sometimes there’s also extra work you’re doing that you shouldn’t be doing (like in the previous section, maybe it’s something that should be escalated!), and in those cases telling them can help you stop doing the work.

they might not know: how the company’s compensation and promotions systems work

This one is a little different from the others because you’re not going to be giving your manager information about this in the same way, but it’s important to be aware of.

I used to think that managers knew everything about compensation / promotions. Then one day I had a really enlightening conversation with my old manager Jay where I was asking a question about how compensation worked, and he said “yeah, I don’t know!”.

I really appreciated how honest he was about it, and it made me realise that there are a LOT of things a manager might not know about how these systems work, like:

- what the system for issuing stock refreshes is

- how raises are calculated when someone gets promoted

- what’s actually expected for a promotion to a given level, and whether or not it’s the same as what’s written down

- whether / why exceptions are made to the rules

- the basic facts about your compensation (I’ve had jobs where managers knew my salary but not what my stock grants were. Apparently this is pretty common!)

what you can do to help: ask about how compensation works!

I’ve found it really valuable to start out conversations about compensation / promotions in a fact-finding way – instead of saying ”hello, i want a raise”, it’s a lot easier for everyone to start with “hey, how does this work? can you explain it to me?”.

This can be especially helpful to new managers because even if they don’t know the answers right away, they can often find out! So if you ask, it’s an opportunity for them to go figure out how these systems work.

You can also get general information about how compensation and promotions work from other managers who are not your manager, if there’s a different manager you have a good relationship who you’d rather have that conversation with.

Some other sources of uncertainty

There are also a lot of other things your manager might be uncertain about:

- They don’t know how priorities are going to change in the future – if there’s a surprise change in priorities, often it’s a surprise to them too!

- They might not know if they’re going to get headcount / how to get headcount: if you’re stressed because your team is overloaded and you’d love to hire someone, they might need to figure out how to get permission to do that themselves

- They may not know how they’re performing. If they’re uncertain about how their next performance review is going to come back or if they just got a bad review, sometimes that uncertainty/stress can trickle down in weird ways. People are human! I think this is good to be aware of as a possible explanation for weird behaviour even if usually they won’t tell you that this is happening.

If you get good at this, it’s a superpower

Being good at telling your manager the right information at the right time and asking for what you need is a superpower. It makes you way more valuable to have on a team (because your manager knows they can trust you to give them the information they need), and it’s more likely that you’ll get what you want (because you’re making it easy for them to do that!).

This skill takes a lot of time to learn but it’s pretty easy to practice. You can take a few minutes to reflect before your 1:1 with your manager and think about what might be important to bring up with them.

The great thing about all of this is that you don’t have to guess: if you’re curious about what your manager knows about a given topic or how you can help get them the information they need, you can just ask them!

If you want to read more about how to build a good relationship with your manager, I wrote a zine called Help! I Have a Manager! about it.

Thanks to Jay Shirley for coming up with the idea for this post with me, and to Akiva Leffert, Allison Kaptur, Camille Fournier, Chirag Davé, Duretti Hirpa, Evy Kassirer, Jay Shirley, Juan Pablo Buriticá, Kamal Marhubi, Marc Hedlund, Marco Rogers, and Ronnie Chen for their comments which made it a lot better. All the problems with it are mine of course :)

A little tool to make DNS queries

Hello! I made a small tool to make DNS queries over the last couple of days, and you can try it at https://dns-lookup.jvns.ca/.

I started thinking about this because I’m working on writing a zine about owning a domain name, and I wanted to encourage people to make a bunch of DNS queries to understand what the responses look like.

So I tried to find other tools are available to make DNS queries.

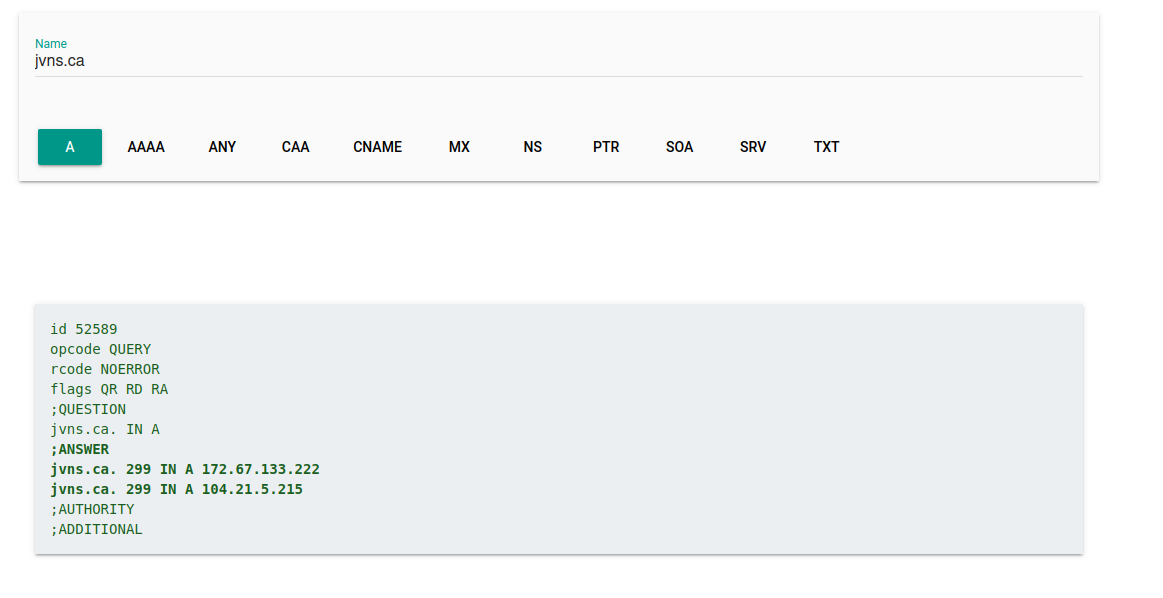

dig is kind of complicated

I usually make DNS queries using dig, like this.

$ dig jvns.ca

; <<>> DiG 9.16.1-Ubuntu <<>> a jvns.ca

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 8447

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 2, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 512

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;jvns.ca. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

jvns.ca. 216 IN A 104.21.5.215

jvns.ca. 216 IN A 172.67.133.222

;; Query time: 40 msec

;; SERVER: fdaa:0:bff::3#53(fdaa:0:bff::3)

;; WHEN: Wed Feb 24 08:53:22 EST 2021

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 68

This is great if you’re used to reading it and if you know which parts to ignore and which parts to pay attention to, but for many people this is too much information.

Like, what does flags: qr rd ra mean? Why does it say QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 2, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1? What is the point of MSG SIZE rcvd: 68? What does IN mean?

I mostly know the answers to these questions because I implemented a toy DNS server one time, but it’s kinda confusing!

google webmaster tools has a nice interface for making DNS queries

Google has a DNS lookup tool with a simple web

interface that lets you type in a domain name, click the kind of record you

want (A, AAAA, etc), and get the response. I was really excited about this

and I thought, “ok, great, this is what I can tell people to use!”.

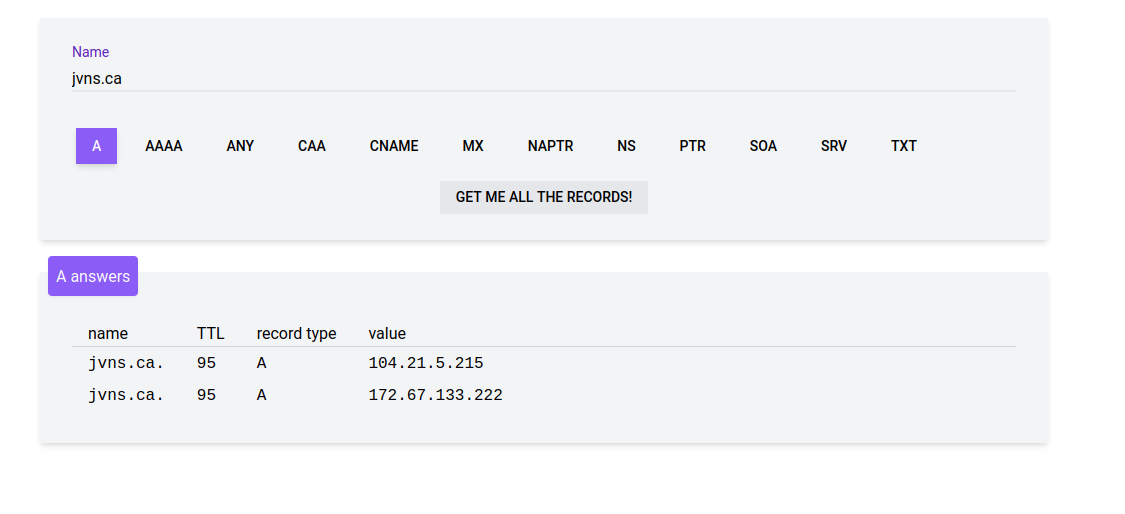

But then I looked at the output of the tool, which you can see in this screenshot:

This is just as bad as dig! (the tool is called “dig”, so it’s not a big surprise, but still :)). So I thought it would be a fun project to make a DNS lookup tool with output that’s more comprehensible by humans

I also wanted to add an option for people to query all the record types at once.

what my lookup tool looks like

I copied the query design from the Google tool because I thought it was nice,

but I put the answers in a table and left out a lot of information I thought

wasn’t necessary for most people like the flags, and the IN (we’re all on the

internet!)

It has a GET ME ALL THE RECORDS button which will make a query for each record type.

I also made a responsive version of the table because it got too wide for a phone:

to get all the record types, you need to make multiple queries

The Google tool has an ANY option which makes an ANY DNS query for the domain. Some DNS

servers support getting all the DNS records with an ANY query, but not all do

– Cloudflare has a good blog post explaining why they removed support for ANY.

So instead of making an ANY query (which usually doesn’t work), the tool I

made just kicks off a query for each record type it wants to know about.

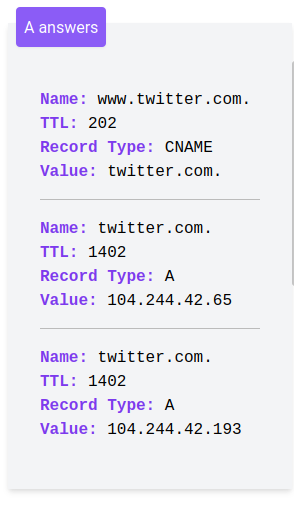

the record type isn’t redundant

At first when I was removing redundant information I thought the record type was redundant too (if you’re making an A query, the responses you get back will be A records, right?), but then I remembered that this actually isn’t true – you can see in this query for A records on www.twitter.com that it replies with a CNAME record because www.twitter.com is CNAMEd to twitter.com.

how it works

The source is on GitHub at https://github.com/jvns/dns-lookup.

It’s basically just 3 files right now:

- dns.js (some Javascript using vue.js)

- index.html

- dns.go is the backend, it’s a Go HTTP handler running on Netlify functions

Using an AWS Lambda-style function was really nice and made this project super easy to deploy. It’s fun not to have worry about servers!

Originally I thought I was going to use the DNS code in the Go standard library, but I ended up using https://github.com/miekg/dns to make the DNS queries because it seemed simpler.

I also tried to use Node’s DNS library to write the backend in Javascript before I switched to Go, but I couldn’t figure out how to get that library to return a TTL for my DNS queries. I think this kind of systems-y thing is generally simpler in Go anyway.

other DNS lookup tools

As always, after I made this, people told me about some other useful tools in the space. Here they are:

- zone.vision, which is nice because it queries the authoritative nameservers for a domain directly

- mxtoolbox.com, which seems a bit more oriented towards MX/SPF queries but does lots more

- the Google DNS lookup tool again

If you know of others I’d love to add them here!

things I might add

some things on my list are:

- maybe reverse DNS queries (technically they’re supported right now if you know how to type in 4.3.2.1.in-addr.arpa, but who has time for that)

- support for more DNS query types (I want to figure how to support all query types without cluttering up the UI too much)

- tooltips explaining what a TTL is

- maybe make the design less of a copy of that Google tool, it has kind of a material design vibe and I don’t know if I love it :)

a link to the tool again

Here’s it is! https://dns-lookup.jvns.ca/.

Firecracker: start a VM in less than a second

Hello! I spent this whole past week figuring out how to use Firecracker and I really like it so far.

Initially when I read about Firecracker being released, I thought it was just a tool for cloud providers to use – I knew that AWS Fargate and https://fly.io used it, but I didn’t think that it was something that I could directly use myself.

But it turns out that Firecracker is relatively straightforward to use (or at least as straightforward as anything else that’s for running VMs), the documentation and examples are pretty clear, you definitely don’t need to be a cloud provider to use it, and as advertised, it starts VMs really fast!

So I wanted to write about using Firecracker from a more DIY “I just want to run some VMs” perspective.

I’ll start out by talking about what I’m using it for, and then I’ll explain a few things I learned about it along the way.

my goal: a game where every player gets their own virtual machine

I’m working on a sort of game to help people learn command line tools by giving them a problem to solve and a virtual machine to solve it in, a little like a CTF. It still basically exists only on my computer, but I’ve been working on it for a while.

Here’s a screenshot of one of the puzzles I’m working on right now. This one is about setting

file extended attributes with setfacl.

why not use containers?

I wanted to use virtual machines and not containers for this project basically

because I wanted to mimic a real production machine that the user has root

access to – I wanted folks to be able to set sysctls, use nsenter, make

iptables rules, configure networking with ip, run perf, basically

literally anything.

the problem: starting a virtual machine is slow

I wanted people to be able to click “Start” on a puzzle and instantly launch a virtual machine. Originally I was launching a DigitalOcean VM every time, but they took about a minute to boot, I was getting really impatient waiting for them every time, and I didn’t think it was an acceptable user experience for people to have to wait a minute.

I also tried using qemu, but for reasons I don’t totally understand, starting a VM with qemu was also kind of slow – it seemed to take at least maybe 20 seconds.

Firecracker can start a VM in less than a second!

Firecracker says this about performance in their specification:

It takes <= 125 ms to go from receiving the Firecracker InstanceStart API call to the start of the Linux guest user-space /sbin/init process.

So far I’ve been using Firecracker to start relatively large VMs – Ubuntu VMs running systemd as an init system – and it takes maybe 2-3 seconds for them to boot. I haven’t been measuring that closely because honestly 5 seconds is fast enough and I don’t mind too much about an extra 200ms either way.

But enough background, let’s talk about how to actually use Firecracker.

here’s a “hello world” script to start a Firecracker VM

I said at the beginning of this post that Firecracker is pretty straightforward to get started with. Here’s how.

Firecracker’s getting started instructions are really good (they just work!) but it was separated into a bunch of steps and I wanted to see everything you have to do together in 1 shell script. So I wrote a short shell script you can use to start a Firecracker VM, and some quick instructions for how to use it.

Running a script like this was the first thing I did when trying to wrap my head around Firecracker. There’s basically 3 steps:

step 1: Download Firecracker from their releases page and put it somewhere

step 2: Run this script as root (you might have to edit the last line with the path to the firecracker binary if it’s not in root’s PATH)

I also put this script in a gist: firecracker-hello-world.sh. The IP addresses here are chosen pretty arbitrarily. Most the script is just writing a JSON file.

set -eu

# download a kernel and filesystem image

[ -e hello-vmlinux.bin ] || wget https://s3.amazonaws.com/spec.ccfc.min/img/hello/kernel/hello-vmlinux.bin

[ -e hello-rootfs.ext4 ] || wget -O hello-rootfs.ext4 https://github.com/firecracker-microvm/firecracker-demo/raw/fea3897ccfab0387ce5cd4fa2dd49d869729d612/xenial.rootfs.ext4

[ -e hello-id_rsa ] || wget -O hello-id_rsa https://raw.githubusercontent.com/firecracker-microvm/firecracker-demo/ec271b1e5ffc55bd0bf0632d5260e96ed54b5c0c/xenial.rootfs.id_rsa

TAP_DEV="fc-88-tap0"

# set up the kernel boot args

MASK_LONG="255.255.255.252"

MASK_SHORT="/30"

FC_IP="169.254.0.21"

TAP_IP="169.254.0.22"

FC_MAC="02:FC:00:00:00:05"

KERNEL_BOOT_ARGS="ro console=ttyS0 noapic reboot=k panic=1 pci=off nomodules random.trust_cpu=on"

KERNEL_BOOT_ARGS="${KERNEL_BOOT_ARGS} ip=${FC_IP}::${TAP_IP}:${MASK_LONG}::eth0:off"

# set up a tap network interface for the Firecracker VM to user

ip link del "$TAP_DEV" 2> /dev/null || true

ip tuntap add dev "$TAP_DEV" mode tap

sysctl -w net.ipv4.conf.${TAP_DEV}.proxy_arp=1 > /dev/null

sysctl -w net.ipv6.conf.${TAP_DEV}.disable_ipv6=1 > /dev/null

ip addr add "${TAP_IP}${MASK_SHORT}" dev "$TAP_DEV"

ip link set dev "$TAP_DEV" up

# make a configuration file

cat <<EOF > vmconfig.json

{

"boot-source": {

"kernel_image_path": "hello-vmlinux.bin",

"boot_args": "$KERNEL_BOOT_ARGS"

},

"drives": [

{

"drive_id": "rootfs",

"path_on_host": "hello-rootfs.ext4",

"is_root_device": true,

"is_read_only": false

}

],

"network-interfaces": [

{

"iface_id": "eth0",

"guest_mac": "$FC_MAC",

"host_dev_name": "$TAP_DEV"

}

],

"machine-config": {

"vcpu_count": 2,

"mem_size_mib": 1024,

"ht_enabled": false

}

}

EOF

# start firecracker

firecracker --no-api --config-file vmconfig.json

step 3: You have a VM running!

You can also SSH into the VM like this, with the SSH key that the script downloaded:

ssh -o StrictHostKeyChecking=false root@169.254.0.21 -i hello-id_rsa

You might notice that if you run ping 8.8.8.8 inside this VM, it doesn’t

work: it’s not able to connect to the outside internet. I think I’m actually

going to use a setup like this for my puzzles where people don’t need to

connect to the internet.

The networking commands and the rootfs image in this script are from the firecracker-demo repository which I found really helpful.

how I put a Firecracker VM on the Docker bridge

I had a couple of problems with this “hello world” setup though:

- I wanted to be able to SSH to them from a Docker container (because I was running my game’s webserver in

docker-compose) - I wanted them to be able to connect to the outside internet

I struggled with trying to understand what a Linux bridge was and how it worked for about a day before figuring out how to get this to work. Here’s a slight modification of the previous script firecracker-hello-world-docker-bridge.sh which runs a Firecracker VM on the Docker bridge

You can run it as root and SSH to the resulting VM like this (the IP is different because it has to be in the Docker subnet).

ssh -o StrictHostKeyChecking=false root@172.17.0.21 -i hello-id_rsa

It basically just changes 2 things:

- There’s an extra

sudo brctl addif docker0 $TAP_DEVto add the VM’s network interface to the Docker bridge - It changes the gateway in the kernel boot args to the Docker bridge network interface’s IP (172.17.0.1)

My guess is that most people probably won’t want to use the Docker bridge, if you just want the VM to be able to connect to the outside internet I think the best way is to create a new bridge.

In my application I’m actually using a bridge called firecracker0 which is a

docker-compose network I made. It feels a little sketchy to be using a bridge

managed by Docker in this way but for now it works so I’ll keep doing that

unless I find a better way.

how I built my own Firecracker images

This “hello world” example is all very well and good, but you might say – ok, how do I build my own images?

Basically you have to do 2 things:

- Make a Linux kernel. I wanted a 5.8 kernel so I used the instructions in the

firecracker docs on creating your own image

for compiling a Linux kernel and they worked. I was kind of intimidated by

this because I’d somehow never compiled a Linux kernel before, but I

followed the instructions and it just worked the first time. I thought it

would be super slow but it actually took less than 10 minutes to compile

from scratch.

- Make an

ext4filesystem image with all the files you want in your VM’s filesystem.

Here’s how I put together my filesystem. Initially I tried downloading Ubuntu’s

focal cloud image and extracting the root partition with dd, but I couldn’t

get it work.

Instead, I did what the Firecracker docs suggested and I built a Docker container and copied the contents of the container into a filesystem image.

Here’s what the Dockerfile I used looked like approximately: (I haven’t

tested this exact Dockerfile but I think it should work). The main things are

that you have to install some kind of init system because the default ubuntu:20.04 image

doesn’t come with one because you don’t need one in a container. I also ran

unminimize to restore some man pages because the container is for interactive

use.

FROM ubuntu:20.04

RUN apt-get update

RUN apt-get install -y init openssh-server

RUN yes | unminimize

# copy over some SSH keys and install other programs I wanted

And here’s the basic shell script I’ve been using to create a filesystem image

from the Docker container. I ran the whole thing as root, but technically you

only have to run mount as root.

IMG_ID=$(docker build -q .)

CONTAINER_ID=$(docker run -td $IMG_ID /bin/bash)

MOUNTDIR=mnt

FS=mycontainer.ext4

mkdir $MOUNTDIR

qemu-img create -f raw $FS 800M

mkfs.ext4 $FS

mount $FS $MOUNTDIR

docker cp $CONTAINER_ID:/ $MOUNTDIR

umount $MOUNTDIR

I’m still not quite sure how much I’m going to like this approach of using Docker containers to create VM images – it feels a bit weird to me but it’s been working fine so far.

I think most people who use Firecracker use a more lightweight init system than systemd and it’s definitely not necessary to use systemd but I think I’m going to stick with systemd for now because I want it to feel mostly like a normal production Linux system and a lot of the production servers I’ve used have used systemd.

Okay, that’s all I have to say about creating images. Let’s talk a bit more about configuring Firecracker.

Firecracker supports either a socket interface or a configuration file

You can start a Firecracker VM 2 ways:

- create a configuration file and run

firecracker --no-api --config-file vmconfig.json - create an API socket and write instructions to the API socket (like they explain in their getting started instructions)

I really liked the configuration file approach for doing some initial experimentation because I found it easier to be able to see everything all in one place. But when integrating Firecracker with my actual application in real life, I found it easier to use the API.

how I wrote a HTTP service that starts Firecracker VMs: use the Go SDK!

I wanted to have a little HTTP service that I could call from my Ruby on Rails server to start new VMs and stop them when I was done with them.

Here’s what the interface looks like – you give it a root image and a kernel and it returns an ID an the VM’s IP address. All of the files paths are just local paths on my machine.

$ http post localhost:8080/create root_image_path=/images/base.ext4 kernel_path=/images/vmlinux-5.8

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

{

"id": "D248122A-1CCA-475C-856E-E3003A913F32",

"ip_address": "172.102.0.4"

}

and then here’s what deleting a VM looks like (I might make this use the DELETE method later to make it more REST-y :) )

$ http post localhost:8080/delete id=D248122A-1CCA-475C-856E-E3003A913F32

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

At first I wasn’t sure how I was going to use the Firecracker socket API to implement this interface, but then I discovered that there’s a Go SDK! This made it way easier to generate the correct JSON, because there were a bunch of structs and the compiler would tell me if I made a typo in a field name.

I basically wrote all of my code so far by copying and modifying code from firectl, a Go command line

tool. The reason I wrote my own tool insted of just using firectl directly was that I

wanted to have a HTTP API that could launch and stop lots of different VMs.

I found the firectl code and the Go SDK pretty easy to understand so I won’t

say too much more about it here.

If you’re interested you can see a gist with my current HTTP service for managing Firecracker VMs which is a huge mess and pretty buggy and not intended for anyone but me to use. It does start VMs successfully though which is an important first step!!!

DigitalOcean supports nested virtualization

Another question I had was: “ok, where am I going to run these Firecracker VMs in production?“. The funny thing about running a VM in the cloud is that cloud instances are already VMs. Running a VM inside a VM is called “nested virtualization” and not all cloud providers support it – for example AWS doesn’t.

Right now I’m using DigitalOcean and I was delighted to see that DigitalOcean does support nested virtualization even on their smallest droplets – I tried running the “hello world” Firecracker script from above and it just worked!

I think GCP supports nested virtualization too but I haven’t tried it. The

official Firecracker documentation suggests using a metal instance on AWS,

probably because Firecracker is made by AWS.

I don’t know what the performance implications of using nested virtualization are yet but I guess I’ll find out!

Firecracker only runs on Linux

I should say that Firecracker uses KVM so it only runs on Linux. I don’t know if there’s a way to start VMs in a similarly fast way on a Mac, maybe there is? Or maybe there’s something special about KVM? I don’t understand how KVM works.

some open questions

A few things I still haven’t figured out:

- Right now I’m not using

jailer, another part of Firecracker that helps further isolate the Firecracker VM by adding someseccomp-BPFrules and other things. Maybe I should be!firectlusesjailerso it would be pretty easy to copy the code that does that. - I still don’t totally understand why Firecracker is fast (or alternatively, why qemu is slow). This LWN article says that it’s because Firecracker emulates less devices than qemu does, but I don’t know exactly which devices are the ones that are making qemu slow to start.

- will it be slow to use nested virtualization?

- I don’t know if it’s possible to run graphical applications in Firecracker, it seems like it might not because it’s intended for servers, but maybe it is possible?

- I’m not sure how many Firecracker VMs I can run at a time on my little $5/month DigitalOcean droplet, I need to do some of experiments.

links

A few people gave me useful links answering some of the above questions.

about why qemu is slower than Firecracker (thanks @tptacek for these):

- Optimizing QEMU boot time (PDF) is really interesting and extremely clearly written

- some slides about qemu-lite, a version of qemu that boots faster and uses less memory

about how Firecracker works:

- Shuveb Hussain’s great post How AWS Firecracker works: a deep dive explains how Firecracker works and demonstrates some of the concepts with a tiny version of Firecracker called . (blog post on Sparkler, Sparkler github repo). Really cool.

- the Firecracker authors’ paper: Firecracker: Lightweight Virtualization for Serverless Applications (there’s a video, slides, and a talk)

on building Firecracker images:

- Álvaro Hernández has a blog post with example code of how he got cloud-init to work with Firecracker. I haven’t tried it yet but it looks really helpful

- @jeromegn mentioned in the HN comments that fly.io uses the devmapper snapshotter. I don’t know what that is yet but here’s the kernel documentation on device-mapper snapshot support

- the “How AWS Firecracker works” post mentions “virtio-fs, which allows efficient sharing of files and directories between hosts and guest. This way, a directory containing the guests’ file system can be on the host, much like how Docker works.” the kernel docs on virtio-fs

software:

- ignite lets you take a container image and run it as a Firecracker VM

Server-sent events: a simple way to stream events from a server

hello! Yesterday I learned about a cool new way of streaming events from a server I hadn’t heard of before: server-sent events! They seem like a simpler alternative to websockets if you only need to have the server send events.

I’m going to talk about what they’re for, how they work, and a couple of bugs I ran into while using them yesterday.

the problem: streaming updates from a server

Right now I have a web service that starts virtual machines, and the client polls the server until the virtual machine is up. But I didn’t want to be doing polling.

Instead, I wanted to stream updates from the server. I told Kamal I was going to implement websockets to do this, and he suggested that server-sent events might be a simpler alternative!

I was like WHAT IS THAT??? It sounded like some weird fancy thing, and I’d never heard of it before. So I looked it up.

server-sent events are just HTTP requests

Here’s how server-sent events work. I was SO DELIGHTED to learn that they’re just HTTP requests.

- The client makes a GET request to (for example)

https://yoursite.com/events - The client sets

Connection: keep-aliveso that we can have a long-lived connection - The server sets a

Content-Type: text/event-streamheader - The server starts sending events that look like this:

event: status

data: one

For example, here’s what some server-sent events look like when I make a request with curl:

$ curl -N 'http://localhost:3000/sessions/15/stream'

event: panda

data: one

event: panda

data: two

event: panda

data: three

event: elephant

data: four

The server can send the events slowly over time, and the client can read them as they arrive. You can also put JSON or whatever you want in the events, like data: {'name': 'ahmed'}

The wire protocol is really simple (just set event: and data: and maybe id: and retry: if you want), so you don’t

need any fancy server libraries to implement server-sent events.

the Javascript code is also super simple (just use EventSource)

Here’s what the browser Javascript code to stream server-sent events looks like. (I got this example from the MDN page on server-sent events)

You can either subscribe to all events, or have different handlers for

different types of events. Here I have a handler that just receives events with

type panda (like our server was sending in the previous section).

const evtSource = new EventSource("/sessions/15/stream", { withCredentials: true })

evtSource.addEventListener("panda", function(event) {

console.log("status", event)

});

the client can’t send updates in the middle

Unlike websockets, server-sent events don’t allow a lot of back-and-forth communication. (it’s in the name – the server sends all the events). The client makes one request at the beginning, and then the server sends a bunch of responses.

if the HTTP connection ends, it’s automatically restarted

One big difference between making an HTTP request with EventSource and a regular HTTP request is this note from the

MDN docs:

By default, if the connection between the client and server closes, the connection is restarted. The connection is terminated with the .close() method.

This is pretty weird, and I was really thrown off it by it at first: I opened a connection, I closed it on the server side, and a couple of seconds later the client made another request to my streaming endpoint!

I think the idea here is that maybe the connection might get accidentally disconnected before it’s done, so the client automatically reopens it to prevent that.

So you have to explicitly close the connection by calling .close() if you don’t want the client

to keep retrying.

there are a few other features

You can also set id: and retry: fields in server-sent events. It looks like

if you set ids on the events the server sends then when reconnecting, the

client will send a Last-Event-ID header with the last ID it received. Cool!

I found the W3C page on server-sent events to be surprisingly readable.

two bugs I ran into while setting up server-sent events

I ran into a couple of problems using server-sent events with Rails that I thought were kinda interesting. One of them was actually caused by nginx, and the other one was caused by rails.

problem 1: I couldn’t pause in between sending events

I had this weird bug where if I did:

def handler

# SSE is Rails' built in server-sent events thing

sse = SSE.new(response.stream, event: "status")

sse.write('event')

sleep 1

sse.write('another event')

end

It would write the first event, but not the second event. I was SO MYSTIFIED by

this and went on a whole digression trying to understand how sleep in Ruby

works. But Cass (another Recurser) pointed me to a Stack Overflow question

where someone else had the same problem, which contained a surprising-to-me

answer!

It turned out that the problem was that my Rails server was behind nginx, and that nginx seemingly by default uses HTTP/1.0 to make requests to upstreams by default (why? in 2021? really? I’m sure there’s a good reason, probably backwards compatibility or something).

So the client (nginx) would just close the connection after the first event sent by the server. I think the reason why it worked if I didn’t pause between sending the 2 events was basically that the server was racing with the client to send the second part of the response before the connection closed, and if I sent it fast enough then the server won the race.

I’m not sure exactly why using HTTP/1.0 made the client close the connection (maybe because the server writes 2 newlines at the end of each event?), but because server-sent events are a pretty new thing it’s not that surprising that they’re not supported by HTTP/1.0 (which is Very Old).

Setting proxy_http_version 1.1 fixed that problem. Hooray!

problem 2: events were being buffered

Once I sorted that out, I had a second problem. This one was actually super easy to debug because Cass had already suggested this other stackoverflow answer as a solution to the previous problem, and while that wasn’t what was causing Problem 1, it DID explain Problem 2.

The problem was with this example code:

def handler

response.headers['Content-Type'] = 'text/event-stream'

# Turn off buffering in nginx

response.headers['X-Accel-Buffering'] = 'no'

sse = SSE.new(response.stream, event: "status")

10.times do

sse.write('event')

sleep 1

end

end

I expected it to return 1 event per second for 10 seconds, but instead it waited 10 seconds and returned 10 events all at once. That’s not how we want streaming to work!

This turned out to because the Rack ETag middleware wanted to calculate an ETag (a hash of the response), and to do that it needed to have the whole response. So I needed to disable ETag generation.

The Stack Overflow answer recommended disabling the Rack ETag middleware entirely, but I didn’t want to do that so I went and looked at the linked github issue.

That github issue suggested a workaround I could apply to just the streaming endpoint, which was to set the Last-Modified header, which apparently bypasses the ETag middleware for some reason.

So I set

headers['Last-Modified'] = Time.now.httpdate

and it worked!!!

I also turned off buffering in nginx by setting the header X-Accel-Buffering: no.

I’m not 100% sure I needed to do that but it seems safer.

stack overflow is amazing

At first I was really 100% committed to debugging both of those bugs from first principles. Cass (another Recurser) pointed me to those two Stack Overflow threads and at first I was skeptical of the solutions those threads were suggesting (I thought “I’m not using HTTP/1.0! And what does the ETag header have to do with anything??“).

But it turned out that I was accidentally using HTTP/1.0, and that the Rack ETag middleware was causing me problems.

So maybe the moral of that story is that sometimes computers interact in weird ways, other people have experienced computers interacting in the exact same weird ways in the past, and Stack Overflow sometimes has answers about why :)

I do think it’s important to not just randomly try things from Stack Overflow (which nobody was suggesting in this case of course!). For both of these I really had to think about them to understand what was happening and why changing those settings made sense.

that’s all!

Today I’m going to keep working on implementing server-sent events, because I spent a lot of yesterday being distracted by the above bugs. It’s always such a delight to learn about a new easy-to-use web technology that I’d never heard of.