Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

The OSI model doesn't map well to TCP/IP

TCP/IP is the set of networking protocols that we use on the modern internet – TCP, UDP, IP, ARP, ICMP, DNS, etc. When I talk about “networking”, I’m basically always talking about TCP/IP.

Many explanations of TCP/IP start with something called the “OSI model”. I don’t use the OSI model when explaining networking because when I first started learning about internet networking I found all of the OSI model explanations really confusing – it wasn’t clear to me at all how the OSI model corresponded to TCP/IP.

So if you’re just starting to learn about networking and you’re confused about the OSI model, here’s an explanation of how it corresponds to TCP/IP, how it doesn’t, and why it’s safe to mostly just ignore it if you don’t find it helpful.

the OSI model has 7 layers

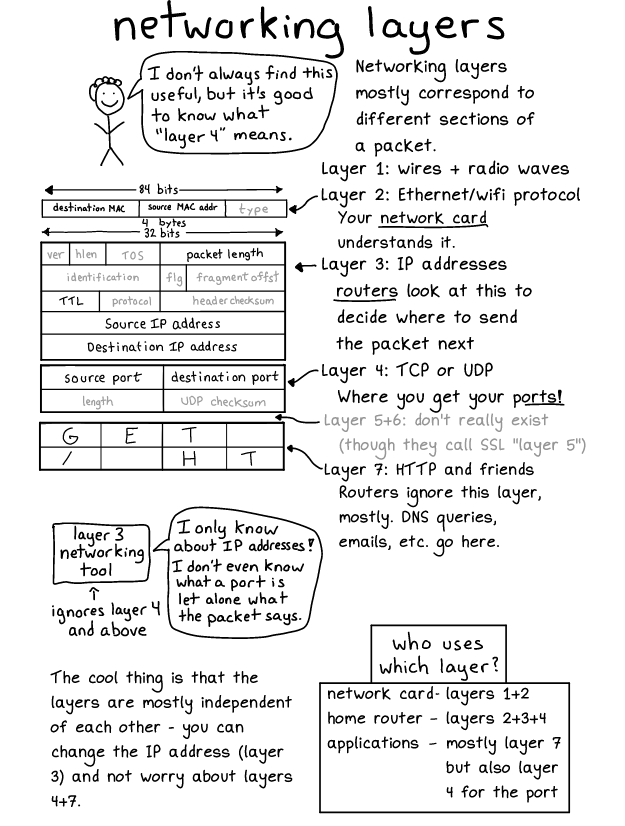

Let’s very briefly discuss what the OSI model is: it’s an abstract model for how networking works with 7 numbered layers:

- Layer 1: physical layer

- Layer 2: data link

- Layer 3: network

- Layer 4: transport

- Layer 5: session

- Layer 6: presentation

- Layer 7: application

I won’t say more about what each of those is supposed to mean, there are a thousand explanations of it online.

how the OSI model corresponds to TCP/IP

Some parts of the OSI model do correspond to TCP/IP. Basically for any TCP or UDP packet you can split up the packet into different sections and give each section a layer number.

- Layer 2 corresponds to Ethernet

- Layer 3 corresponds to IP

- Layer 4 corresponds to TCP or UDP (or ICMP etc)

- Layer 7 corresponds to whatever is inside the TCP or UDP packet (for example a DNS query)

Here’s a diagram from my Networking! ACK! zine showing how you can assign layers to different parts of a packet.

I just noticed that for some reason this is a UDP packet containing the start of a HTTP request which is unrealistic, but let’s go with it, you could make a UDP packet like that if you wanted :). I think I did that to save space.

Now that we’ve talked about how the OSI model does correspond to TCP/IP, let’s talk about how it doesn’t!

people refer to layers 2, 3, 4, and 7 all the time

It’s important to know about the OSI model because the terms “layer 2”, “layer 3”, “layer 4” and “layer 7” are used a LOT. You’ll hear about “layer 2 routing”, “layer 7 load balancers”, “layer 4 load balancers”, etc.

So even thought I don’t really use those terms myself when talking about networking, I need to understand them to be able to read documentation and understand what people are saying.

there’s no layer 5 or 6 in TCP/IP

I’ve heard a few different interpretations of what layers 5 or 6 could mean in TCP/IP, including:

- TLS is layer 6

- TCP is actually layers 5 + 6 + 7 smushed together

But layers 5 and 6 definitely don’t have a clear correspondence like “every layer has a corresponding header in the TCP packet” the way layers 2, 3, and 4 do.

And I’ve never seen anyone actually refer to layer 5 or 6 in practice when talking about TCP/IP, even though people talk about layers 2, 3, 4, and 7 all the time.

what layer is an ARP packet?

Also, some parts of TCP/IP don’t fit well into the OSI model even around layers 2-4 – for example, what layer is an ARP packet?

ARP is a protocol for discovering what MAC address corresponds to an IP address: when a machine wants to know who has a certain IP address, it sends out an ARP message saying “help! who is 192.168.1.1?” and it’ll get a response from the owner of the IP saying “it’s me! I’m 192.168.1.1”

ARP packets contain IP addresses and IP addresses are layer 3, but when people talk about “layer 3” packets they usually mean a packet which have an IP header, and ARP packets don’t have an IP header, they just have an Ethernet header and then some data on top of that which contains an IP.

the OSI model is a literal description of some obsolete protocols

So, if the OSI model doesn’t literally describe TCP/IP, where did it come from?

Some very brief research on Wikipedia says that in addition to an abstract description of 7 layers, the OSI model also contained a bunch of specific protocols implementing those layers. Apparently this happened during the Protocol Wars in the 70s and 80s, where the OSI model lost and TCP/IP won.

This explains why the OSI model doesn’t really correspond that well to TCP/IP, since if the OSI protocols had “won” then the OSI model would correspond exactly to how internet networking actually works.

you can talk about specific network protocols instead of using layer numbers

When talking about networking, instead of using numbered layers I like to instead just talk about specific networking protocols I mean. Like instead of “layer 2” I’ll use something like “Ethernet” or “MAC address”. I’ve written many blog posts talking about MAC addresses and zero posts talking about “layer 2”.

As another example, when talking about load balancers usually I say “HTTP load balancer” instead of “layer 7 load balancer”. Basically every layer 7 load balancer I’ve used has been a HTTP load balancer, and if it’s not using HTTP then I’d rather know which other protocol it’s using!

that’s all!

Hopefully this will help clear things up for somebody! I wish someone had told me when I started learning networking that I could just learn approximately how layers 2, 3, 4, and 7 of the OSI model relate to TCP/IP and then ignore everything else about it.

I put all of my comics online!

Hello! As you probably know, I write a lot of comics about programming, and I publish collections of them as zines you can buy at https://wizardzines.com.

I also usually post the comics on Twitter as I write them. But there are a lot of problems with just posting them to Twitter, like:

- the pages are hard to find. For example, if you want to find the one on

socat, you can search twitter and you’ll find it, but then you have to somehow magically guess what words I used in the tweet, and also sort through a bunch of other tweets. - they’re annoying to link to. Twitter isn’t really the best user interface for this sort of thing.

- I can’t make updates. Twitter doesn’t have an edit button!

- work that never made it into a zine is basically impossible to find. For example I wrote 12 pages of a sequel to “bite size linux” but never quite finished it, and it’s basically impossible for anyone to find those pages. Or I have a couple of pages about Kubernetes I wrote one time that will probably never make it into a zine either.

If someone wants to see the page on socat, I’d really like them to just be able to find it at https://wizardzines.com/comics/socat

now they’re all online in one place!

the tl;dr is that (almost) all of my comics are now online in one place at https://wizardzines.com/comics. Hooray!

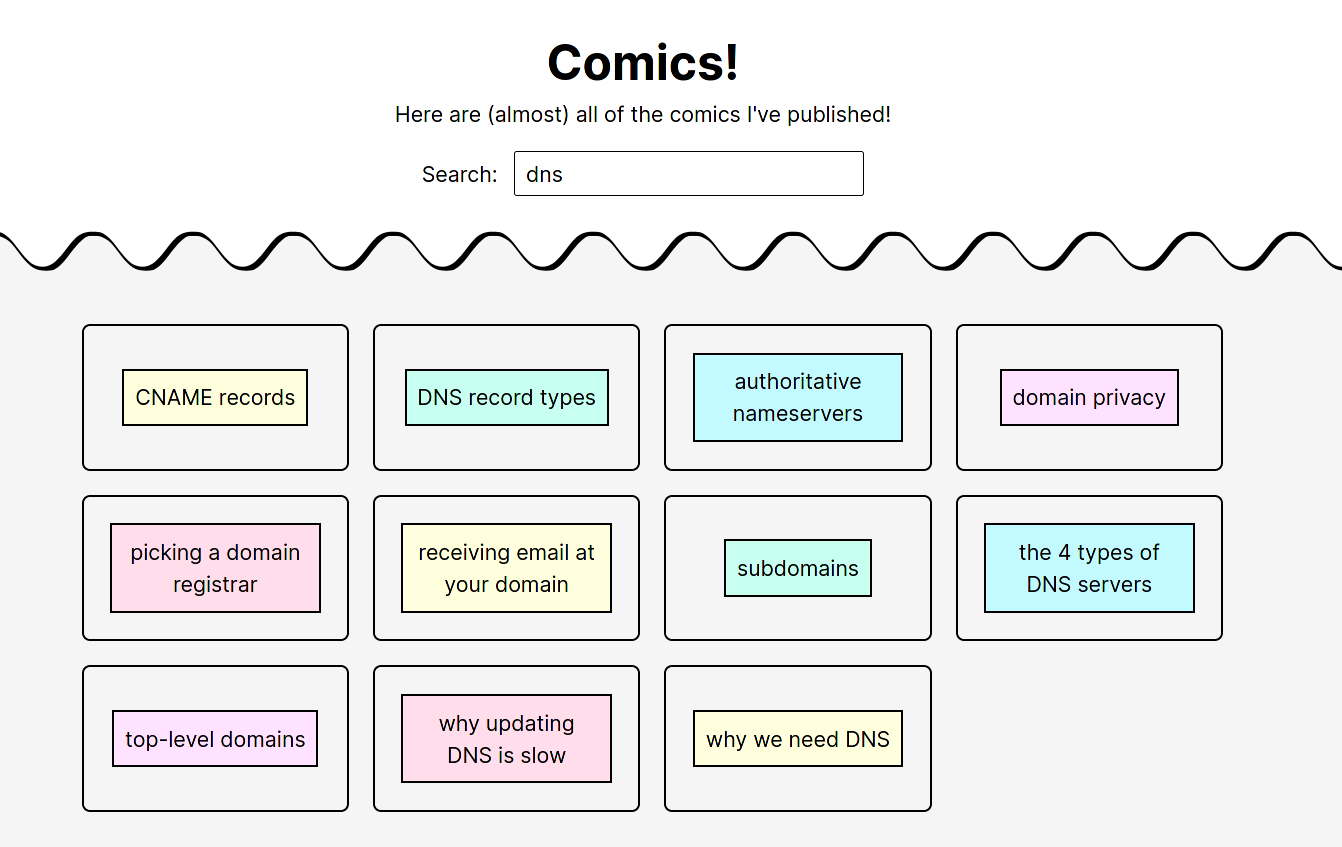

you can search!

There are 273 comics right now which is a lot, so I’ve added a very simple search using list.js. Here’s what it looks like.

It searches based on the title and also a few keywords I manually added, which is why “authoritative nameservers” matches the search “dns”.

I wrote a small custom search function that only matches starting at the beginning of the word, so that the search “tar” doesn’t give you “start”. It feels pretty good to use.

If you want to read the pages from the Bite Size Linux sequel I mentioned that I started writing 2 years ago and never finished, you can search for “linux2”.

what’s not there

Some parts of the zines aren’t there just because it wouldn’t make sense – for example most of the zines have an introduction and a conclusion page, and those pages don’t really work as a standalone comic.

Also a lot of the pages from my free zines aren’t there yet because a lot of them don’t work as well as standalone pages. I might add them in the future though, we’ll see.

Other things that are missing that I think I will add:

- the comics from https://drawings.jvns.ca

- any other pages I’ve posted over the years on Twitter that aren’t in a zine, assuming that I can find them (for example scenes from distributed systems)

why I didn’t do this earlier

This isn’t actually that hard of a change to make technically – I just needed to write some Python scripts and write a little search function.

But I felt a bit worried about making all the comics more easily available online because – what if I put them online and then nobody wants to buy the zines anymore?

I decided this week not to worry about that and just do it because I’m really excited about being able to easily link any comic that I want.

The zine business is going really well in general so I think it’s a lot nicer to operate with a spirit of abundance instead of a spirit of scarcity.

Notes on building debugging puzzles

Hello! This week I started building some choose-your-own-adventure-style puzzles about debugging networking problems. I’m pretty excited about it and I’m trying to organize my thoughts so here’s a blog post!

The two I’ve made so far are:

I’ll talk about how I came to this idea, design decisions I made, how it works, what I think is hard about making these puzzles, and some feedback I’ve gotten so far.

why this choose-your-own-adventure format?

I’ve been thinking a lot about DNS recently, and how to help people troubleshoot their DNS issues. So on Tuesday I was sitting in a park with a couple of friends chatting about this.

We started out by talking about the idea of flowcharts (“here’s a flowchart that will help you debug any DNS problem”). I’ve don’t think I’ve ever seen a flowchart that I found helpful in solving a problem, so I found it really hard to imagine creating one – there are so many possibilities! It’s hard to be exhaustive! It would be disappointing if the flowchart failed and didn’t give you your answer!

But then someone mentioned choose-your-own-adventure games, and I thought about something I could relate to – debugging a problem together with someone who knows things that I don’t!

So I thought – what if I made a choose-your-own-adventure game where you’re given the symptoms of a specific networking bug, and you have to figure out how to diagnose it?

I got really excited about this and immediately went home and started putting something together in Twine.

Here are some design decisions I’ve made so far. Some of them might change.

design decision: the mystery has 1 specific bug

Each mystery has one very specific bug, ideally a bug that I’ve actually run into in the past. Your mission is to figure out the cause of the bug and fix it.

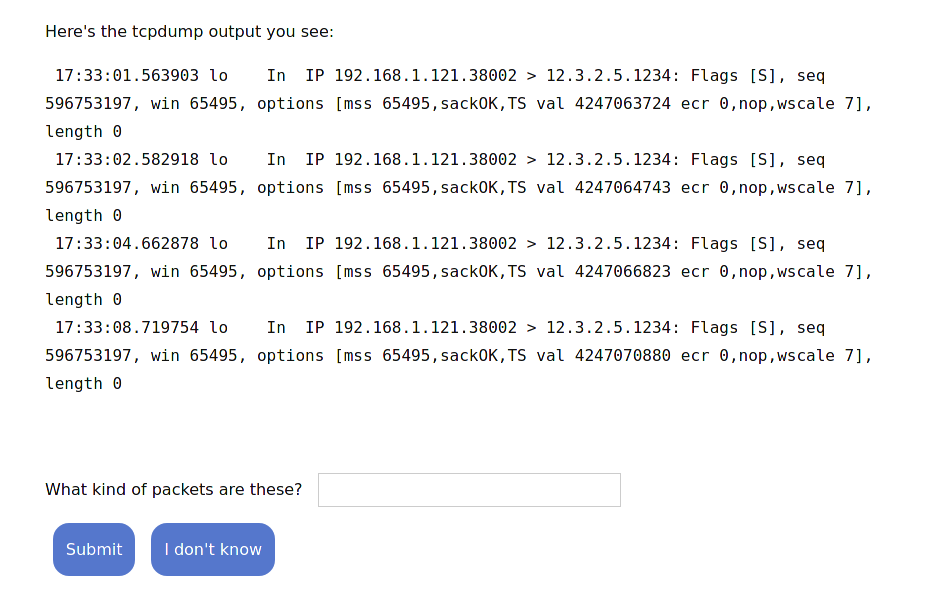

design decision: show people the actual output of the tools they’re using

All of the bugs I’m starting with are networking issues, and the way you solve them is to use various tools (like dig, curl, tcpdump, ping, etc) to get more information.

Originally I thought of writing the game like this:

- You choose “Use curl”

- It says “You run

<command>. You see that the output tells you<interpretation>“

But I realized that immediately interpreting the output of a command for someone is extremely unrealistic – one of the biggest problems with using some of these command line networking tools is that their output is hard to interpret!

So instead, the puzzle:

- Asks what tool you want to use

- Tells you what command they ran, and shows you the output of the command

- Asks you to interpret the output (you type it in in a freeform text box)

- Tells you the “correct” interpretation of the output and shows you how you could have figured it out (by highlighting the relevant parts of the output)

This really lines up with how I’ve learned about these tools in real life – I don’t learn about how to read all of the output all at once, I learn it in bits and pieces by debugging real problems.

design decision: make the output realistic

This is sort of obvious, but in order to give someone output to help them diagnose a bug, the output needs to be a realistic representation of what would actually happen.

I’ve been doing this by reproducing the bug in a virtual machine (or on my laptop), and then running the commands in the same way I would to fix the bug in real life and paste their output.

Reproducing the bug isn’t always easy, but once I’ve reproduced it it makes building the puzzle much more straightforward than trying to imagine what tcpdump would theoretically output in a given situation.

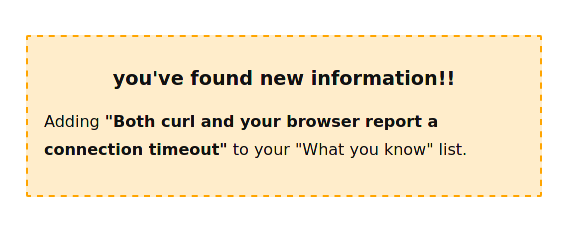

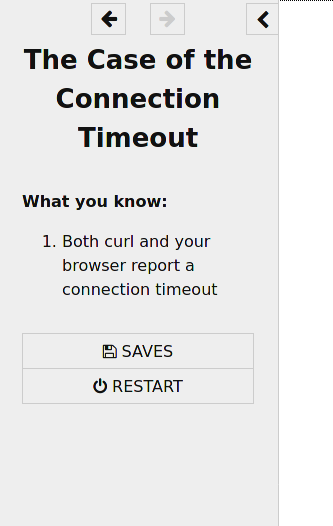

design decision: let people collect “knowledge” throughout the mystery

When I debug, I think about it as slowly collecting new pieces of information as I go. So in this mystery, every time you figure out a new piece of information, you get a little box that looks like this:

And in the sidebar, you have a sort of “inventory” that lists all of the knowledge you’ve collected so far. It looks like this:

design decision: you always figure out the bug

My friend Sumana pointed out an interesting difference between this and normal choose-your-own-adventure games: in the choose-your-own-adventure games I grew up reading, you lose a lot! You make the wrong choice, and you fall into a pit and die.

But that’s not how debugging works in my experience. When debugging, if you make a “wrong” choice (for example by making a guess about the bug that isn’t correct), there’s no cost except your time! So you can always go back, keep trying, and eventually figure out what’s going on.

I think that “you always win” is sort of realistic in the sense that with any bug you can always figure out what the bug is, given:

- enough time

- enough understanding of how the systems you’re debugging work

- tools that can give you information about what’s happening

I’m still not sure if I want all bugs to result in “you fix the bug!” – sometimes bugs are impossible to fix if they’re caused by a system that’s outside of your control! One really interesting idea Sumana had was to have the resolution sometimes be to tell someone else (like your ISP) about the issue, which made me think about how it’s a useful skill to be able to write a really clear and convincing bug report so that the people with the ability to fix the bug will be able to easily recognize that you’ve accurately diagnosed the issue.

design decision: include red herrings sometimes

In debugging in real life, there are a lot of red herrings! Sometimes you see something that looks weird, and you spend three hours looking into it, and then you realize that wasn’t it at all.

One of the mysteries right now has a red herring, and the way I came up with it was that I ran a command and I thought “wait, the output of that is pretty confusing, it’s not clear how to interpret that”. So I just included the confusing output in the mystery and said “hey, what do you think it means?”.

One thing I like about including red herrings is that it lets me show how you can prove what the cause of the bug isn’t which is even harder than proving what the cause of the bug is.

design decision: use free form text boxes

Here’s an example of what it looks like to be asked to interpret some output. You’re asked a question and you fill in the answer in a text box.

I think I like using free form text boxes instead of multiple choice because it feels a little more realistic to me – in real life, when you see some output like this, you don’t get a list of choices!

design decision: don’t do anything with what you enter in the text box

No matter what you enter in the text box (or if you say “I don’t know”), exactly the same thing happens. It’ll send you to a page that tells you the answer and explains the reasoning. So you have to think about what you think the answer might be, but if you get it “wrong”, it’s no big deal.

The reason I’m doing this is basically “it’s very easy to implement”, but I think there’s maybe also something nice about it for the person using it – if you don’t know, it’s totally okay! You can learn something new and keep moving! You don’t get penalized for your “wrong” answers in any way.

design decision: the epilogue

At the end of the game, there’s a very short epilogue where it talks about how likely you are to run into this bug in real life / how realistic this is. I think I need to expand on this to answer other questions people might have had while going through it, but I think it’s going to be a nice place to wrap up loose ends.

how long each one takes to play: 5 minutes

People seem to report so far that each mystery takes about 5 minutes to play, which feels reasonable to me. I think I’m most likely to extend this by making lots of different 5-minute mysteries rather than making one really long mystery, but we’ll see.

what’s hard: reproducing the bug

Figuring out how to reproduce a given bug is actually not that easy – I think I want to include some pretty weird bugs, and setting up a computer where that bug is happening in a realistic way isn’t actually that easy. I think this just takes some work and creativity though.

what’s hard: giving realistic options

The most common critique I got was of the form “In this situation I would have done X but you didn’t include X as an option”. Some examples of X: “ping the problem host”, “ssh to the problem host and run tcpdump there”, “look at the log file”, “use netstat”, etc.

I think it’s possible to make a lot of progress on this with playtesting – if I playtest a mystery with a bunch of people and ask them to tell me when there was an option they wish they had, I can add that option pretty easily!

Because I can actually reproduce the bug, providing an option like “run

netstat” is pretty straightforward – all I have to do is go to the VM where

I’ve reproduced the bug, run netstat, and put the output into the game.

A couple of people also said that the game felt too “linear” or didn’t branch enough. I’m curious about whether that will naturally come out of having more realistic options.

how it works: it’s a Twine game!

I felt like Twine was the obvious choice for this even though I’d never used it before – I’d heard so many good things about it over the years.

You can see all of the source code for The Case of the Connection Timeout in connection-timeout.twee and common.twee, which has some shared code between all the games.

A few notes about using Twine:

- I’m using SugarCube, the sugarcube docs are very good

- I’m using tweego to translate the

.tweefiles in to a HTML page. I started out using the visual Twine editor to do my editing but switched totweegopretty quickly because I wanted to use version control and have a more text-based workflow. - The final output is one big HTML file that includes all the images and CSS and Javascript inline. The final HTML files are about 800K which seems reasonable to me.

- I base64-encode all the images in the game and include them inline in the file

- The Twine wiki and forums have a lot of great information and between the Twine wiki, the forums, and the Sugarcube docs I could pretty easily find answers to all my questions.

I used pretty much the exact Twine workflow from Em Lazerwalker’s great post A Modern Developer’s Workflow For Twine.

I won’t explain how Twine works because it has great documentation and it would make this post way too long.

some feedback so far

I posted this on Twitter and asked for feedback. Some common pieces of feedback I got:

things people liked:

- maybe 180 “I love this, this was so fun, I learned something new”

- A bunch of people specifically said that they liked learning how to interpret tcpdump’s output format

- A few people specifically mentioned that they liked the “what you know” list and the mechanic of hunting for clues and how it breaks down the debugging process.

some suggestions for improvements:

- Like I mentioned before, lots of people said “I wanted to try X but it wasn’t an option”

- One of the puzzles had a resolution to the bug that some people found unsatisfying (they felt it was more of a workaround than a fix, which I agreed with). I updated it to add a different resolution that was more satisfying.

- There were some technical issues (it could be more mobile-friendly, one of the images was hard to read, I needed to add a “Submit” button to one of the forms)

- Right now the way the text boxes work is that no matter what you type, the exact same thing happens. Some people found this a bit confusing, like “why did it act like I answered correctly if my answer was wrong”. This definitely needs some work.

some goals of this project

Here’s what I think the goals of this project are:

- help people learn about tools (like tcpcdump, dig, and curl). How do you use each tool? What questions can they be used to answer? How do you interpret their output?

- help people learn about bugs. There are some super common bugs that we run into over and over, and once you see a bug once it’s easier to recognize the same bug in the future.

- help people get better at the debugging process (gathering data, asking questions)

what experience is this trying to imitate?

Something I try to keep in mind with all my projects is – what real-life experience does this reproduce? For example, I kind of think of my zines as being the experience “your coworker explains something to you in a really clear way”.

I think the experience here might be “you’re debugging a problem together with your coworker and they’re really knowledgeable about the tools you’re using”.

that’s all!

I’m pretty excited about this project right now – I’m going to build at least a couple more of these and see how it goes! If things go well I might make this into my first non-zine thing for sale – maybe it’ll be a collection of 12 small debugging mysteries! We’ll see.

What problems do people solve with strace?

Yesterday I asked on Twitter about what problems people are solving with strace and as usual everyone really delivered! I got 200 answers and then spent a bunch of time manually categorizing them into 9 categories of problems.

All of the problems are about either finding files a program depends on, figuring out why a program is stuck or slow, or finding out why a program is failing. These generally matched up with what I use strace for myself, but there were some things I hadn’t thought of too!

I’m not going to explain what strace is in this post but I have a free zine about it and a talk and lots of blog posts.

problem 1: where’s the config file?

The #1 most popular problem was “this program has a configuration file and I don’t know where it is”. This is probably my most common use for strace too, because it’s such a simple question.

This is great because there are a million ways for a program to document where

its config file is (in a man page, on its website, in --help, etc), but

there’s only one way for it to actually open it (with a system call!)

problem 2: what other files does this program depend on?

You can also use strace to find other types of files a program depends on, like:

- dynamically linked libraries (“why is my program loading the wrong version of this

.sofile?“) like this ruby problem I debugged in 2014 - where it’s looking for its Ruby gems (Ruby specifically came up a few times!)

- SSL root certificates

- a game’s save files

- a closed-source program’s data files

- which node_modules files aren’t being used

problem 3: why is this program hanging?

You have a program, it’s just sitting there doing nothing, what’s going

on? This one is especially easy to answer because a lot of the time you just

need to run strace -p PID and look at what system call is currently running.

You don’t even have to look through hundreds of lines of output!

The answer is usually ‘waiting for some kind of I/O’. Some possible answers for “why is this stuck” (though there are a lot more!):

- it’s polling forever on a

select() - it’s

wait()ing for a subprocess to finish - it’s making a network request to something that isn’t responding

- it’s doing

write()but it’s blocked because the buffer is full - it’s doing a

read()on stdin and it’s waiting for input

Someone also gave a nice example of using strace to debug a stuck df: ‘with strace df -h you can find the stuck mount and unmount it”.

problem 4: is this program stuck?

A variation on the previous one: sometimes a program has been running for longer than you expected, and you just want to know if it’s stuck or of it’s still making progress.

As long as the program makes system calls while it’s running, this is super easy to answer with strace – just strace it and see if it’s making new system calls!

problem 5: why is this program slow?

You can use strace as a sort of coarse profiling tool – strace -t will show

the timestamp of each system call, so you can look for big gaps and find the culprit.

Here are 9 short stories from Twitter of people using strace to debug “why is this program slow?”.

- Back in 2000, a Java-based web site that I helped support was dying under modest load: pages loaded slowly, if at all. We straced the J2EE application server and found that it was reading class files one. byte. at. a. time. Devs weren’t using BufferedReader, classic Java mistake.

- Optimizing app startup times… running strace can be an eye-opening experience, in terms of the amount of unnecessary file system interaction going on (e.g. open/read/close on the same config file over and over again; loading gobs of font files over a slow NFS mount, etc)

- Asked myself why reading from session files in PHP (usually <100 bytes)

was incredibly slow. Turned out some

flock-syscalls took ~60s - A program was behaving abnormally slow. Used strace to figure out it was re-initializing its internal pseudo-random number generator on every request by reading from /dev/random and exhausting entropy

- Last thing I remember was attaching to a job worker and seeing just how many network calls it was making (which was unexpected).

- Why is this program so slow to start? strace shows it opening/reading the same config file thousands of times.

- Server using 100% CPU time randomly with low actual traffic. Turns out it’s hitting the number of open files limit accepting a socket, and retrying forever after getting EMFILE and not reporting it.

- A workflow was running super slow but no logs, ends up it was trying to do a post request that was taking 30s before timing out and then retrying 5 times… ends up the backend service was overwhelmed but also had no visibility

- using strace to notice that gethostbyname() is taking a long time to return (you can’t see the

gethostbynamedirectly but you can see the DNS packets in strace)

problem 6: hidden permissions errors

Sometimes a program is failing for a mysterious reason, but the problem is just that there’s some file that it doesn’t have permission to open. In an ideal world programs would report those errors (“Error opening file /dev/whatever: permission denied”), but of course the world is not perfect, so strace can really help with this!

This is actually the most recent thing I used strace for: I was using an

AxiDraw pen plotter and it printed out an inscrutable error message when I

tried to start it. I straced it and it turned out that my user just didn’t

have permission to open the USB device.

problem 7: what command line arguments are being used?

Sometimes a script is running another program, and you want to know what command line flags it’s passing!

A couple of examples from Twitter:

- find what compiler flags are actually being used to build some code

- a command was failing due to having too long a command line

problem 8: why is this network connection failing?

Basically the goal here is just to find which domain / IP address the network

connection is being made to. You can look at the DNS request to find the domain

or the connect system call to find the IP.

In general there are a lot of stories about using strace to debug network

issues when tcpdump isn’t available for some reason or just because it’s what

the person is more familiar with.

problem 9: why does this program succeed when run one way and fail when run in another way?

For example:

- the same binary works on one machine, fails on another machine

- works when you run it, fails when spawned by a systemd unit file

- works when you run it, fails when you run it as “su - user /some/script”

- works when you run it, fails when run as a cron job

Being able to compare the strace output in both cases is very helpful. Though my first step when debugging “this works as my user and fails when run in a different way on the same computer” would be “look at my environment variables”.

problem 10: how does this Linux kernel API work?

Another one quite a few people mentioned is figuring out how a Linux kernel API (for example netlink, io_uring, hdparm, I2C, etc).

Even though these APIs are usually documented, sometimes the documentation is confusing or there aren’t very many examples, so often it’s easier to just strace an existing application and see how it interacts with the Linux kernel.

problem 11: general reverse engineering

strace is also great for just generally figuring out “how does this program work?“. As a simple example of this, here’s a blog post on figuring out how killall works using strace.

what I’m doing with this: slowly building some challenges

The reason I’m thinking about this is that I’ve been slowly working on some challenges to help people practice using strace and other command line tools. The idea is that you’re given a problem to solve, a terminal, and you’re free to solve it in any way you want.

So my goal is to use this to build some practice problems that you can solve with strace that reflect the kinds of problems that people actually use it for in real life.

that’s all!

There are probably more problems that can be solved with strace that I haven’t covered here – I’d love to hear what I’ve missed!

I really loved seeing how many of the same uses came up over and over and over again – at least 20 different people replied saying that they use strace to find config files. And as always I think it’s really delightful how such a simple tool (“trace system calls!”) can be used to solve so many different kinds of problems.

A tool to spy on your DNS queries: dnspeep

Hello! Over the last few days I made a little tool called dnspeep that lets you see what DNS queries your computer is making, and what responses it’s getting. It’s about 250 lines of Rust right now.

I’ll talk about how you can try it, what it’s for, why I made it, and some problems I ran into while writing it.

how to try it

I built some binaries so you can quickly try it out.

For Linux (x86):

wget https://github.com/jvns/dnspeep/releases/download/v0.1.0/dnspeep-linux.tar.gz

tar -xf dnspeep-linux.tar.gz

sudo ./dnspeep

For Mac:

wget https://github.com/jvns/dnspeep/releases/download/v0.1.0/dnspeep-macos.tar.gz

tar -xf dnspeep-macos.tar.gz

sudo ./dnspeep

It needs to run as root because it needs access to all the DNS packets your computer is sending. This is the same reason tcpdump needs to run as root – it uses libpcap which is the same library that tcpdump uses.

You can also read the source and build it yourself at https://github.com/jvns/dnspeep if you don’t want to just download binaries and run them as root :).

what the output looks like

Here’s what the output looks like. Each line is a DNS query and the response.

$ sudo dnspeep

query name server IP response

A firefox.com 192.168.1.1 A: 44.235.246.155, A: 44.236.72.93, A: 44.236.48.31

AAAA firefox.com 192.168.1.1 NOERROR

A bolt.dropbox.com 192.168.1.1 CNAME: bolt.v.dropbox.com, A: 162.125.19.131

Those queries are from me going to neopets.com in my browser, and the

bolt.dropbox.com query is because I’m running a Dropbox agent and I guess it phones

home behind the scenes from time to time because it needs to sync.

why make another DNS tool?

I made this because I think DNS can seem really mysterious when you don’t know a lot about it!

Your browser (and other software on your computer) is making DNS queries all the time, and I think it makes it seem a lot more “real” when you can actually see the queries and responses.

I also wrote this to be used as a debugging tool. I think the question “is this a DNS problem?” is harder to answer than it should be – I get the impression that when trying to check if a problem is caused by DNS people often use trial and error or guess instead of just looking at the DNS responses that their computer is getting.

you can see which software is “secretly” using the Internet

One thing I like about this tool is that it gives me a sense for what programs

on my computer are using the Internet! For example, I found out that something

on my computer is making requests to ping.manjaro.org from time to time

for some reason, probably to check I’m connected to the internet.

A friend of mine actually discovered using this tool that he had some corporate monitoring software installed on his computer from an old job that he’d forgotten to uninstall, so you might even find something you want to remove.

tcpdump is confusing if you’re not used to it

My first instinct when trying to show people the DNS queries their computer is

making was to say “well, use tcpdump”! And tcpdump does parse DNS packets!

For example, here’s what a DNS query for incoming.telemetry.mozilla.org. looks like:

11:36:38.973512 wlp3s0 Out IP 192.168.1.181.42281 > 192.168.1.1.53: 56271+ A? incoming.telemetry.mozilla.org. (48)

11:36:38.996060 wlp3s0 In IP 192.168.1.1.53 > 192.168.1.181.42281: 56271 3/0/0 CNAME telemetry-incoming.r53-2.services.mozilla.com., CNAME prod.data-ingestion.prod.dataops.mozgcp.net., A 35.244.247.133 (180)

This is definitely possible to learn to read, for example let’s break down the query:

192.168.1.181.42281 > 192.168.1.1.53: 56271+ A? incoming.telemetry.mozilla.org. (48)

A?means it’s a DNS query of type Aincoming.telemetry.mozilla.org.is the name being qeried56271is the DNS query’s ID192.168.1.181.42281is the source IP/port192.168.1.1.53is the destination IP/port(48)is the length of the DNS packet

And in the response breaks down like this:

56271 3/0/0 CNAME telemetry-incoming.r53-2.services.mozilla.com., CNAME prod.data-ingestion.prod.dataops.mozgcp.net., A 35.244.247.133 (180)

3/0/0is the number of records in the response: 3 answers, 0 authority, 0 additional. I think tcpdump will only ever print out the answer responses though.CNAME telemetry-incoming.r53-2.services.mozilla.com,CNAME prod.data-ingestion.prod.dataops.mozgcp.net., andA 35.244.247.133are the three answers56271is the responses ID, which matches up with the query’s ID. That’s how you can tell it’s a response to the request in the previous line.

I think what makes this format the most difficult to deal with (as a human who just wants to look at some DNS traffic) though is that you have to manually match up the requests and responses, and they’re not always on adjacent lines. That’s the kind of thing computers are good at!

So I decided to write a little program (dnspeep) which would do this matching

up and also remove some of the information I felt was extraneous.

problems I ran into while writing it

When writing this I ran into a few problems.

- I had to patch the

pcapcrate to make it work properly with Tokio on Mac OS (this change). This was one of those bugs which took many hours to figure out and 1 line to fix :) - Different Linux distros seem to have different versions of

libpcap.so, so I couldn’t easily distribute a binary that dynamically links libpcap (you can see other people having the same problem here). So I decided to statically compile libpcap into the tool on Linux. I still don’t really know how to do this properly in Rust, but I got it to work by copying thelibpcap.afile intotarget/release/depsand then just runningcargo build. - The

dns_parsercrate I’m using doesn’t support all DNS query types, only the most common ones. I probably need to switch to a different crate for parsing DNS packets but I haven’t found the right one yet. - Becuase the

pcapinterface just gives you raw bytes (including the Ethernet frame), I needed to write code to figure out how many bytes to strip from the beginning to get the packet’s IP header. I’m pretty sure there are some cases I’m still missing there.

I also had a hard time naming it because there are SO MANY DNS tools already (dnsspy! dnssnoop! dnssniff! dnswatch!). I basically just looked at every synonym for “spy” and then picked one that seemed fun and did not already have a DNS tool attached to it.

One thing this program doesn’t do is tell you which process made the DNS query, there’s a tool called dnssnoop I found that does that. It uses eBPF and it looks cool but I haven’t tried it.

there are probably still lots of bugs

I’ve only tested this briefly on Linux and Mac and I already know of at least one bug (caused by not supporting enough DNS query types), so please report problems you run into!

The bugs aren’t dangerous though – because the libpcap interface is read-only the worst thing that can happen is that it’ll get some input it doesn’t understand and print out an error or crash.

writing small educational tools is fun

I’ve been having a lot of fun writing small educational DNS tools recently.

So far I’ve made:

- https://dns-lookup.jvns.ca (a simple way to make DNS queries)

- https://dns-lookup.jvns.ca/trace.html (shows you exactly what happens behind the scenes when you make a DNS query)

- this tool (

dnspeep)

Historically I’ve mostly tried to explain existing tools (like dig or

tcpdump) instead of writing my own tools, but often I find that the output of

those tools is confusing, so I’m interested in making more friendly ways to see

the same information so that everyone can understand what DNS queries their

computer is making instead of just tcpdump wizards :).