Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Why Browsers Get Built

There are only two-and-a-half reasons to build a browser, and they couldn't be more different in intent and outcome, even when they look superficially similar. Learning to tell the difference is helpful for browser project managers and engineers, but also working web developers who struggle to develop theories of change for affecting browser teams.

Like Platform Adjacency Theory and The Core Web Platform Loop, this post started1 as a set of framing devices that I've been sketching on whiteboards for the best part of a decade. These lenses aren't perfect, but they provide starting points for thinking about the complex dynamics of browsers, OSes, "native" platforms, and the standards-based web platform.

The reasons to build browsers are most easily distinguished by the OSes they support and the size and composition of their teams ("platform" vs. "product"). Even so, there are subtleties that throw casual observers for a loop. In industrial-scale engineering projects like browser construction, headcount is destiny, but it isn't the whole story.

Web As Platform

This is simultaneously the simplest and most vexing reason to build a browser.

Under this logic, browsers are strategically important to a broader business, and investments in platforms are investments in their future competitiveness compared with other platforms, not just other browsers. But none of those investments come good until the project has massive scale.

This strategy is exemplified by the ambitions of Netscape, crisply captured by Andreesen's quip that the goal was to render Windows "a poorly debugged set of device drivers".

The idea is that the web is where the action is, and that the browser winning more user Jobs To Be Done follows from increasing the web platform's capability. This developer-enabling flywheel aims to liberate computing from any single OS, supporting a services model.

A Web As Platform play depends on credibly keeping up with expansions in underlying OS features. The goal is to deliver safe portable, interoperable, and effective versions of important capabilities at a fast enough clip to maintain faith in the web as a viable ongoing investment.

In some sense it's a confidence-management exercise. A Web As Platform endgame requires the platform increases expressive capacity year over year. It must do as many new things each year as new devices can, even if the introduction of those features is delayed for the web by several years; the price of standards.

Platform-play browsers aim to grow and empower the web ecosystem, rather than contain it or treat it as a dying legacy. Examples of this strategic orientation include Netscape, Mozilla (before it lost the plot), Chrome, and Chromium-based Edge (on a good day).

Distinguishing Traits

- Ship on many OSes and not just those owned by the sponsor

- Large platform teams (>200 people and/or >40% of the browser team)

- Visible, consistent investments in API leadership and capability expansion

- Balanced benchmark focus

- Large standards engagement footprint

The OS Agenda

There are two primary tactical modes of this strategic posture, both serving the same goal: to make an operating system look good by enabling a corpus of web content to run well on it while maintaining a competitive distance between the preferred (i.e., native, OS-specific) platform and the hopefully weaker web platform.

The two sub-variants differ in ambition owing to the market positions of their OS sponsors.

Browsers as Bridges

OSes deploy browsers as a bridge for users into their environment when they're underdogs or fear disruption.

Of course, it would be better from the OS vendor's perspective if everyone simply wrote software specifically tailored to their proprietary platform, maximising OS feature differentiation. But smart vendors also know that's not possible when an OS isn't dominant.

OS challengers, therefore, strike a bargain. For the price of developing a browser, they gain the web's corpus of essential apps and services, serving to "de-risk" the purchase of a niche device by offering broad compatibility with existing software through the web. If they do a good job, a conflicted short-term investment can yield enough browser share to enable a future turn towards moat tactics (see below). Examples include Internet Explorer 3-6 as well as Safari on Mac OS X and the first iPhone.2

Conversely, incumbents fearing disruption may lower their API drawbridges and allow the web's power to expand far enough that the incumbent can gain share, even if it's not for their favoured platform; the classic example here being Internet Explorer in the late 90s. Once Microsoft knew it had Netscape well and truly beat, it simply disbanded the IE team, leaving the slowly rusting husk of IE to decay. And it would have worked, too, if it weren't for those pesky Googlers pushing IE6 beyond what was "possible"!

Browsers as Moats

Without meaningful regulation, powerful incumbents can use anticompetitive tactics to suppress the web's potential to disrupt the OS and tilt the field towards the incumbent's proprietary software ecosystem.

This strategy works by maintaining sufficient browser share to influence developer choices while never allowing the browser team to deliver features sufficient to disrupt OS-specific alternatives.

In practice, moats are arbitrage on the unwillingness of web developers to understand or play the game, e.g. by loudly demanding timely features or recommending better browsers to users. Incumbents know that web developers are easily convinced to avoid "non standard" features and are happy to invent excuses for them. It's cheap to add a few features here and there to show you're "really trying," despite underfunding browser teams so much they can never do more than a glorified PR for the OS. This was the strategy behind IE 7-11 and EdgeHTML. Even relatively low share browsers can serve as effective moats if they can't be supplanted by competitive forces.

Apple has perfected the strategy, preventing competitors from even potentially offering disruptive features. This adds powerfully to the usual moat-digger's weaponisation of consensus processes. Engineering stop-energy in standards and quasi-standards bodies is nice, but it is so much more work than simply denying anyone the ability to ship the features that might threaten the proprietary agenda.

Tipping Points

Bridge and moat tactics appear very different, but the common thread is control with an intent to suppress web platform expansion. In both cases, the OS will task the browser team to heavily prioritise integrations with the latest OS and hardware features at the expense of more broadly useful capabilities — e.g. shipping "notch" CSS and "force touch" events while neglecting Push.

Browser teams tasked to build bridges can grow quickly and have remit that looks similar to a browser with a platform agenda. Still, the overwhelming focus starts (and stays) on existing content, seldom providing time or space to deliver powerful new features to the Web. A few brave folks bucked this trend, using the fog of war to smuggle out powerful web platform improvements under a more limited bridge remit; particularly the IE 4-6 crew.

Teams tasked with defending (rather than digging) a moat will simply be starved by their OS overlords. Examples include IE 7+ and Safari from 2010 onward. It's the simplest way to keep web developers from getting uppity without leaving fingerprints. The "soft bigotry of low expectations", to quote a catastrophic American president.

Distinguishing Traits

- Shipped only to the sponsor's OSes

- Browser versions tied to OS versions

- Small platform teams (<100 people and/or <30% of the browser team)

- Skeleton standards footprint

- Extreme focus on benchmarks of existing content

- Consistent developer gaslighting regarding new capabilities

- Anti-competitive tactics against competitors to maintain market share

- Inconsistent feature leadership, largely focused on highlighting new OS and hardware features

- Lagging quality

Searchbox Pirates

This is the "half-reason"; it's not so much a strategic posture as it is environment-surfing.

Over the years, many browsers that provide little more than searchboxes atop someone else's engine have come and gone. They lack staying power because their teams lack the skills, attitudes, and management priorities necessary to avoid being quickly supplanted by a fast-following competitor pursuing one of the other agendas.

These browsers also tend to be short-lived because they do not build platform engineering capacity. Without agency in most of their codebase, they either get washed away in unmanaged security debt, swamped by rebasing challenges (i.e., a failure to "work upstream"). They also lack the ability to staunch bleeding when their underlying engine fails to implement table-stakes features, which leads to lost market share.

Historical examples have included UC Browser, and more recently, the current crop of "secure enterprise browsers" (Chromium + keyloggers). Perhaps more controversially, I'd include Brave and Arc in this list, but their engineering chops make me think they could cross the chasm and choose to someday become platform-led browsers. They certainly have leaders who understand the difference.

Distinguishing Traits

- Shipped to many OSes

- Tiny platform teams (<20 people or <10% of the browser team)

- Little benchmark interest or focus

- No platform feature leadership

- No standards footprint

- Platform feature availability lags the underlying engine (e.g., UI and permissions not hooked up)

- Platform potentially languishes multiple releases behind "upstream"

Implications

This model isn't perfect, but it has helped me tremendously in reliably predicting the next moves of various browser players, particularly regarding standards posture and platform feature pace.3

The implications are only sometimes actionable, but they can help us navigate. Should we hope that a vendor in a late-stage browser-as-moat crouch will suddenly turn things around? Well, that depends on the priorities and fortunes of the OS, which dictate the strategy of their browser team.

Similarly, a Web As Platform strategy will maximise a browser's reach and its developers' potential, albeit at the occasional expense of end-user features.

The most important takeaway for developers may be what this model implies about browser choice. Products with an OS-first agenda are always playing second fiddle to a larger goal that does not put web developers first, second, or even third. Coming to grips with this reality lets us more accurately recommend browsers to users that align with our collective interests in a vibrant, growing Web.

FOOTNOTES

I hadn't planned to write this now, but an unruly footnote in an upcoming post, along with Frances' constant advice to break things up, made me realise that I already had 90% of it of ready. ⇐

IE and iOS Safari demonstrate the capacity of OS vendors to burn bridges, stranding web developers in an unattractive bind through of disinvestment in browsers they control which retain blocking market share.

As a result, it is not fear of engine monoculture that keeps me up at night, but rather the difficulty of displacing entrenched browsers from vendors with a proprietary agenda. ⇐

Modern-day Mozilla presents a puzzle within this model.

In theory, Mozilla's aims and interests align with growing the web as a platform; expanding its power to enable a larger market for browsers, and through it, a larger market for Firefox.

In practice, that's not what's happening. Despite investing almost everything it makes back into browser development, Mozilla has also begun to slow-walk platform improvements. It walked away from PWAs and has continued to spread FUD about device APIs and other features that would indicate an appetite for an expansive vision of the platform.

In a sense, it's playing the OS Agenda, but without an OS to profit from or a proprietary platform to benefit with delay and deflection. This is vexing, but perhaps expected within an organisation that has entered a revenue-crunch crouch. Another way to square the circle is to note that the Mozilla Manifesto doesn't actually speak about the web at all. If the web is just another fungible application running atop the internet (which the manifesto does centre), then it's fine for the web to be frozen in time, or even shrink.

Still, Mozilla leadership should be thinking hard about the point of maintaining an engine. Is it to hold the coats of proprietary-favouring OS vendors? Or to make the web a true competitor? ⇐

Home Screen Advantage

After weeks of confusion and chaos, Apple's plan to kneecap the web has crept into view, menacing a PWApocalypse as the March 6th deadline approaches for compliance with the EU's Digital Markets Act (DMA).

The DMA requires Apple to open the iPhone to competing app stores, and its lopsided proposal for "enabling" them is getting most of the press. But Apple knows it has native stores right where it wants them. Cupertino's noxious requirements will take years to litigate. Meanwhile, potential competitors are only that.

But Cupertino can't delay the DMA's other mandate: real browsers, downloaded from Apple's own app store. Since it can't bar them outright, it's trying to raise costs on competitors and lower their potential to disrupt Apple's cozy monopoly. How? By geofencing browser choice and kneecapping web apps, all while gaslighting users about who is breaking their web apps.

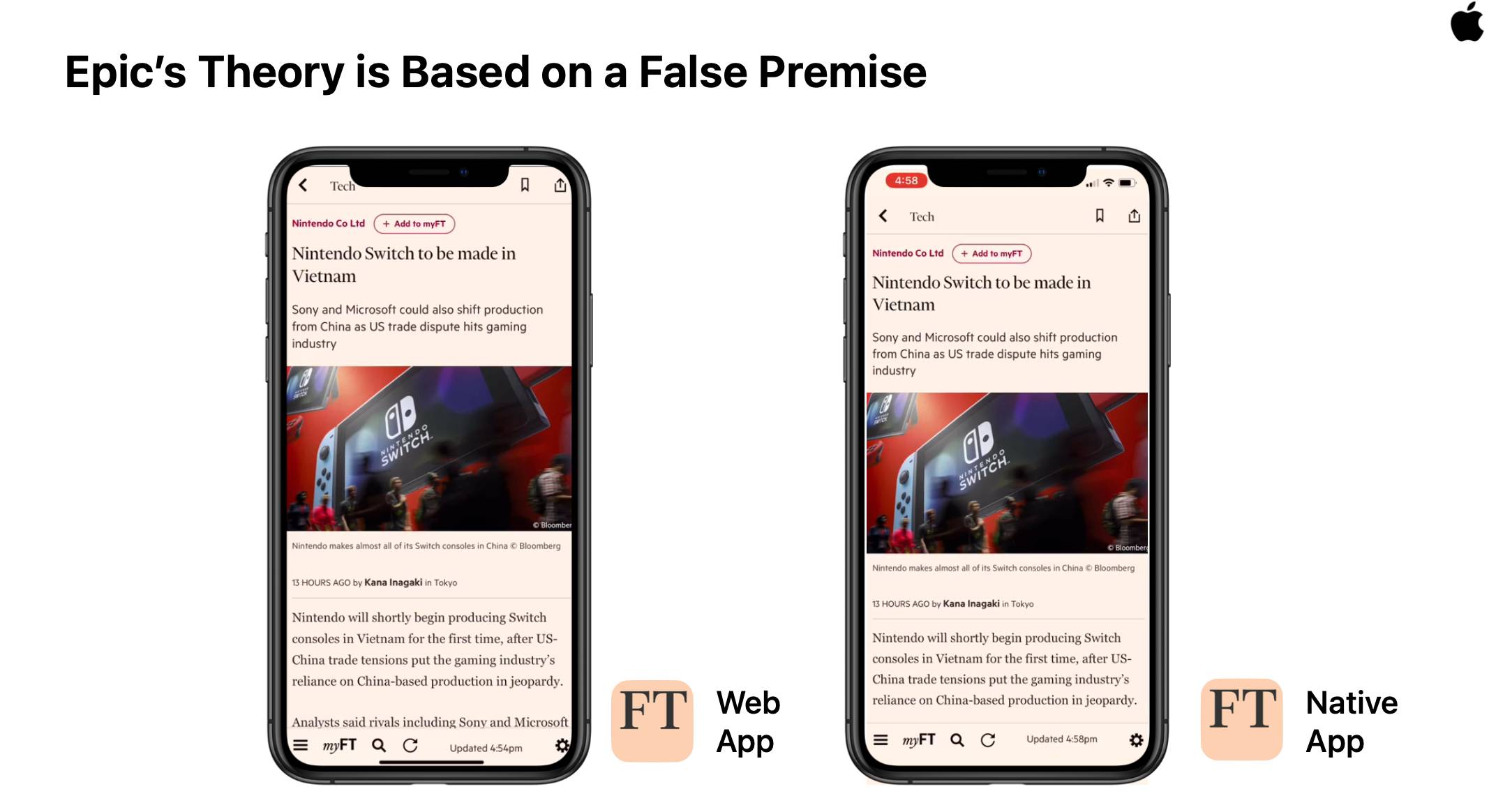

The immediate impact of iOS 17.4 in the EU will be broken apps and lost data, affecting schools, governments, startups, gamers, and anyone else with the temerity to look outside the one true app store for even a second. None of this is required by the DMA, as demonstrated by continuing presence of PWAs and the important features they enable on Windows and Android, both of which are in the same regulatory boat.

The data loss will be catastrophic for many, as will the removal of foundational features. Here's what the landscape looks like today vs. what Apple is threatening:

| PWA Capability | Windows | Android | iOS 17.3 | iOS 17.4 |

| App-like UI | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

| Settings Integration | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

| Reliable Storage | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

| Push Notifications | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

| Icon Badging | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

| Share-to PWA | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

| App Shortcuts | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Device APIs | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

Apple's support for powerful web apps wasn't stellar, but this step in the wrong direction will just so happen to render PWAs useless to worldwide businesses looking to reach EU users.

Apple's interpretation of the DMA appears to be that features not available on March 6th don't need to be shared with competitors, and it doesn't want to share web apps. The solution almost writes itself: sabotage PWAs ahead of the deadline and give affected users, businesses, and competitors minimal time to react.

Cupertino's not just trying to vandalise PWAs and critical re-engagement features for Safari; it's working to prevent any browser from ever offering them on iOS. If Apple succeeds in the next two weeks, it will cement a future in which the mobile web will never be permitted to grow beyond marketing pages for native apps.

By hook or by crook, Apple's going to maintain its home screen advantage.

The business goal is obvious: force firms back into the app store Apple taxes and out of the only ecosystem it can't — at least not directly. Apple's justifications range from unfalsifiable smokescreens to blatant lies, but to know it you have to have a background in browser engineering and the DMA's legalese. The rest of this post will provide that context. Apologies in advance for the length.

If you'd like to stop reading here, take with you the knowledge that Cupertino's attempt to scuttle PWAs under cover of chaos is exactly what it appears to be: a shocking attempt to keep the web from ever emerging as a true threat to the App Store and blame regulators for Apple's own malicious choices.

And they just might get away with it if we don't all get involved ASAP.

Chaos Monkey Business

Two weeks ago, Apple sprung its EU Digital Markets Act (DMA) compliance plans on the world as a fait accomplis.

The last-minute unveil after months of radio silence were calculated to give competitors minimal time to react to the complex terms, conditions, and APIs. This tactic tries to set Apple's proposal as a negotiating baseline, forcing competitors to burn time and money arguing down plainly unacceptable terms before they can enter the market.

For native app store hopefuls, this means years of expensive disputes before they can begin to access an artificially curtailed market. This was all wrapped in a peevish, belligerant presentation, which the good folks over at The Platform Law Blog have covered in depth.

Much of the analysis has focused on the raw deal Apple is offering native app store competitors, missing the forest for the trees: the threat Apple can't delay by years comes from within.

Deep in the sub-basement of Apple's tower of tomfoolery are APIs and policies that purport to enable browser engine choice. If you haven't been working on browsers for 15 years, the terms might seem reasonable, but to these eyes they're anything but. OWA has a lengthy dissection of the tricks Apple's trying to pull.

The proposals are maximally onerous, but you don't have to take my word for it; here's Mozilla:

We are ... extremely disappointed with Apple’s proposed plan to restrict the newly-announced BrowserEngineKit to EU-specific apps. The effect of this would be to force an independent browser like Firefox to build and maintain two separate browser implementations — a burden Apple themselves will not have to bear.

Apple’s proposals fail to give consumers viable choices by making it as painful as possible for others to provide competitive alternatives to Safari.

This is another example of Apple creating barriers to prevent true browser competition on iOS.

The strategy is to raise costs and lower the value of porting browsers to iOS. Other browser vendors have cited exactly these concerns when asked about plans to bring their best products to iOS. Apple's play is to engineer an unusable alternative then cite the lack of adoption to other regulators as proof that mandating real engine choice is unwise.

Instead of facilitating worldwide browser choice in good faith, Apple's working to geofence progress; classic "divide and conquer" stuff, justified with serially falsified security excuses. Odious, brazen, and likely in violation of the DMA, but to the extent that it will now turn into a legal dispute, that's a feature (not a bug) from Apple's perspective.

When you're the monopolist, delay is winning.

But Wait! There's More!

All of this would be stock FruitCo doing anti-competitive FruitCo things, but they went further, attempting to silently shiv PWAs and blame regulators for it. And they did it in the dead of the night, silently disabling important features as close to the DMA compliance deadline as possible.

It's challenging, verging on impossible, to read this as anything but extrordinary bad faith, but Apple's tactics require context to understand.

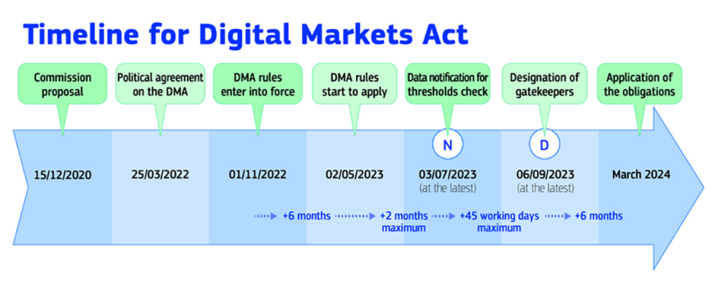

The DMA came into force in 2022, putting everyone (including Apple) on notice that their biggest platforms and products would probably be "designated", and after designation, they would have six months to "comply". The first set of designation decisions went out last Sept, obligating Android, Windows, iOS, Chrome, and Safari to comply no later than March 6th, 2024.

A maximally aggressive legal interpretation might try to exploit ambiguity in what it means to comply and when responsibilities actually attach.

Does compliance mean providing open and fair access starting from when iOS and Safari were designated, or does compliance obligation only attach six months later? The DMA's text is not ironclad here:

10: The gatekeeper shall comply with the obligations laid down in Articles 5, 6 and 7 within 6 months after a core platform service has been listed in the designation decision pursuant to paragraph 9 of this Article.

Firms looking to comply maliciously might try to remove troublesome features just before a compliance deadline, then argue they don't need to share them with competitors becuse they weren't available before the deadline set in. Apple looks set to argue, contra everyone else subject to the DMA, that the moment from which features must be made interoperable is the end of the fair-warning period, not the date of designation.

This appears to be Apple's play, and it stinks to high heavens.

What's At Risk?

Apple's change isn't merely cosmetic. In addition to immediate data loss, FruitCo's change will destroy:

- App-like UI:

Web apps are no longer going to look or work like apps in the task manager, systems settings, or any other surface. Homescreen web apps will be demoted to tabs in the default browser. - Reliable storage:

PWAs were the only exemption to Apple's (frankly silly) seven day storage eviction policy, meaning the last safe harbour for anyone trying to build a serious, offline-first experience just had the rug pulled out from under them. - Push Notifications:

Remember how Apple gaslit web developers over Web Push for the best part of a decade? And remember how, when they finally got around to it, did a comically inept job? Recall fretting and about how shite web Push Notifications look and work for iOS users? Well, rest easy, because they're going away too. - App Icon Badging:

A kissing cousin of Push, Icon Badging allows PWAs to ambiently notify users of new messages, something iOS native apps have been able to do for nearly 15 years.

Removal of one would be a crisis. Together? Apple's engineering the PWApocalypse.

You can't build credible mobile experiences without these features. A social network without notifications? A notetaking app that randomly loses data? Businesses will get the message worldwide: if you want to be on the homescreen and deliver services that aren't foundationally compromised, the only game in town is Apple's app store.

Apple understands even the most aggressive legal theories about DMA timing wouldn't support kneecapping PWAs after March 6th. Even if you believe (as I do) their obligations attached back in September, there's at least an argument to be tested. Cupertino's white-shoe litigators would be laughed out of court and Apple would get fined ridiculous amounts for non-compliance if it denied these features to other browsers after the fair-warning period. To preserve the argument for litigation, it was necessary to do the dirty deed ahead of the last plausible deadline.

Not With A Bang, But With A Beta

The first indication something was amiss was a conspicuous lack of APIs for PWA support in the BrowserEngineKit documentation, released Feb 1st alongside Apple's peevish, deeply misleading note that attempted to whitewash malicious compliance in a thin coat of security theatre.

Two days later, after developers inside the EU got their hands on the iOS 17.4 Beta, word leaked out that PWAs were broken. Nothing about the change was documented in iOS Beta or Safari release notes. Developers filed plaintive bugs and some directly pinged Apple employees, but Cupertino remained shtum. This created panic and confusion as the windows closed for DMA compliance and the inevitable iOS 17.4 final release ahead of March 6th.

Two more betas followed, but no documentation or acknowledgement of the "bug." Changes to the broken PWA behavior were introduced, but Apple failed to acknowledge the issue or confirm that it was intentional and therefore likely to persist. After two weeks of growing panic from web developers, Apple finally copped to crippling the only open, tax-free competitor to the app store.

Apple's Feb 15th statement is a masterclass in deflection and deceit. To understand why requires a deep understanding of browsers internals and how Apple's closed PWA — sorry, "home screen web app" — system for iOS works.

TL;DR? Apple's cover story is horseshit, stem to stern. Cupertino ought to be ashamed and web developers are excused for glowing incandescent with rage over being used as pawns; first ignored, then gaslit, and finally betrayed.

Lies, Damned Lies, and "Still, we regret..."

I really, really hate to do this, but Brandolini's Law dictates that to refute Apple's bullshit, I'm going to need to go through their gibberish excuses line-by-line to explain and translate.

Q: Why don’t users in the EU have access to Home Screen web apps?

Translation: "Why did you break functionality that has been a foundational part of iOS since 2007, but only in the EU?"

To comply with the Digital Markets Act, Apple has done an enormous amount of engineering work to add new functionality and capabilities for developers and users in the European Union — including more than 600 new APIs and a wide range of developer tools.

Translation: "We're so very tired, you see. All of this litigating to avoid compliance tuckered us right out. Plus, those big meanies at the EU made us do work. It's all very unfair."

It goes without saying, but Apple's burden to add APIs it should have long ago provided for competing native app stores has no bearing whatsoever on its obligation to provide fair access to APIs that browser competitors need. Apple also had the same two years warning as everyone else. It knew this was coming, and 11th hour special pleading has big "the dog ate my homework" energy.

The iOS system has traditionally provided support for Home Screen web apps by building directly on WebKit and its security architecture. That integration means Home Screen web apps are managed to align with the security and privacy model for native apps on iOS, including isolation of storage and enforcement of system prompts to access privacy impacting capabilities on a per-site basis.

Finally! A recitation of facts.

Yes, iOS has historically forced a uniquely underpowered model on PWAs, but iOS is not unique in providing system settings integration or providing durable storage or managing PWA permissions. Many OSes and browsers have created the sort of integration infrastructure that Apple describes. These systems leave the question of how PWAs are actually run (and where their storage lives) to the browser that installs them, and the sky has yet to fall. Apple is trying to gussy up preferences and present them as hard requirements without justification.

Apple is insinuating that it can't provide API surface areas to allow the sorts of integrations that others already have. Why? Because it might involve writing a lot of code.

Without this type of isolation and enforcement, malicious web apps could read data from other web apps and recapture their permissions to gain access to a user’s camera, microphone or location without a user’s consent.

Keeping one website from abusing permissions or improperly accessing data from another website is what browsers do. It's Job #1.

Correctly separating principals is the very defintion of a "secure" browser. Every vendor (save Apple) treats subversion of the Same Origin Policy as a showstopping bug to be fixed ASAP. Unbelieveable amounts of engineering go to ensuring browsers overlay stronger sandboxing and more restrictive permissions on top of the universally weaker OS security primitives — iOS very much included.

Browser makers have become masters of origin separation because they run totally untrusted code from all over the internet. Security is paramount because browsers have to be paranoid. They can't just posture about how store reviews will keep users safe; they have to do the work.

Good browsers separate web apps better than bad ones. It's rich that Apple of all vendors is directly misleading this way. Its decade+ of under-investment in WebKit ensured Safari was less prepared for Spectre and Meltdown and Solar Winds than alternative engines. Competing browsers had invested hundreds of engineer years into more advanced Site Isolation. To this day, Apple's underfunding and coerced engine monoculture put all iOS users at risk.

With that as background, we can start to unpack Apple's garbled claims.

Cupertino is that it does not want to create APIs for syncing permission state through the thin shims every PWA-supporting OS uses to make websites first class. It doesn't want to add APIs for attributing storage use, clearing state, toggling notifications, and other common management tasks. This is a preference, but it is not responsive to Apple's DMA obligations.

If those APIs existed, Apple would still have a management question, which its misdirections also allude to. But these aren't a problem in practice. Every browser offering PWA support would happily sign up to terms that required accurate synchronization of permission state between OS surfaces and web origins, in exactly the same way they treat cross-origin subversion as a fatal bug to be hot-fixed.

Apple's excusemaking is a mirror of Cupertino's years of scaremongering about alternate browser engine security, only to take up my proposal more-or-less wholesale when the rubber hit the road.

Nothing about this is monumental to build or challenging to manage; FruitCo's just hoping you don't know better. And why would you? The set of people who understand these details generously number in the low dozens.

Browsers also could install web apps on the system without a user’s awareness and consent.

Apple know this is a lie.

They retain full control over the system APIs that are called to add icons to the homescreen, install apps, and much else. They can shim in interstitial UI if they feel like doing so. If iOS left this to Safari and did not include these sorts of precautions, those are choices Apple has made and has been given two years notice to fix.

Cupertino seems to be saying "bad things might happen if we continued to do a shit job" and one can't help but agree. However, that's no way out of the DMA's obligations.

Addressing the complex security and privacy concerns associated with web apps using alternative browser engines would require building an entirely new integration architecture that does not currently exist in iOS and was not practical to undertake given the other demands of the DMA and the very low user adoption of Home Screen web apps.

[CITATION NEEDED]

Note the lack of data? Obviously this sort of unsubstantiated bluster fails Hitchen's Razor, but that's not the full story.

Apple is counting on the opacity of its own web suppression to keep commenters from understanding the game that's afoot. Through an enervating combination of strategic underinvestment and coerced monoculture, Apple created (and still maintains) a huge gap in discoverability and friction for installing web apps vs. their native competition. Stacking the deck for native has taken many forms:

- Preventing web apps from gaining distribution in the app store by explicit policy.

- "Smart Banners" that let sites easily offer installation of their native counterparts.

- Steadfast refusal to implement analagous features for PWAs or provide competing browsers the OS and DOM APIs they need to do so.

- Burying Web App installation behind a "Share Sheet" UI that users and developers complain is incredibly hard to discover, forcing site owners to build clunky intersitials.

- Denying competitors the necessary API access to offer better install UI and only providing the underwhelming "Share Sheet" option last year, a full 15 years after Safari.

This campaign of suppression has been wildly effective. If users don't know they can install PWAs, it's because Safari never tells them, and until this time last year, neither could any other browser. Developers also struggled to justify building them because Apple's repression extended to neglect of critical features, opening and maininting a substantial capability gap.

If PWAs use on iOS is low, that's a consequence of Apple's own actions. On every other OS where I've seen the data, not only are PWAs a success, they are growing rapidly. Perhaps that's why Apple feels a need to mislead by omission and fail to provide data to back their claim.

And so, to comply with the DMA’s requirements, we had to remove the Home Screen web apps feature in the EU.

Bullshit.

Apple's embedded argument expands to:

- We don't want to comply with the plain-letter language of the law.

- To avoid that, we've come up with a legal theory of compliance that's favourable to us.

- To comply with that (dubious) theory, and to avoid doing any of the work we don't want to do, we've been forced to bump off the one competitor we can't tax.

Neat, tidy, and comprised entirely of bovine excrement.

EU users will be able to continue accessing websites directly from their Home Screen through a bookmark with minimal impact to their functionality. We expect this change to affect a small number of users. Still, we regret any impact this change — that was made as part of the work to comply with the DMA — may have on developers of Home Screen web apps and our users.

Translation: "Because fuck you, that's why"

The DMA doesn't require Apple to torpedo PWAs.

Windows and Android will continue supporting them just fine. Apple apparently hopes it can convince users to blame regulators for its own choices. Cupertino's counting on the element of surprise plus the press's poorly developed understanding of the situation to keep blowback from snowballing into effective oppostion.

The Point

There's no possible way to justify a "Core Technology Fee" tax on an open, interoperable, standardsized platform that competitors would provide secure implementations of for free. What Apple's attempting isn't just some hand-wavey removal of a "low use" feature ([CITATION NEEDED]), it's sabotage of the only credible alternative to its app store monopoly.

LOL.

Businesses will get the message: from now on, the only reliable way to get your service under the thumb, or in the notification tray, of the most valuable users in the world is to capitulate to Apple's extortionate App Store taxes.

If the last 15 years are anything to judge by, developers will take longer to understand what's going on, but this is an attempt to pull a "Thoughts on Flash" for the web. Apple's suppression of the web has taken many forms over the past decade, but the common thread has been inaction and anti-competitive scuppering of more capable engines. With one of those pillars crumbling, the knives glint a bit more brightly. This is Apple once and for all trying to relegate web development skills to the dustbin of the desktop.

Not only will Apple render web apps unreliable for Safari users, FruitCo is setting up an argument to prevent competitors from ever delivering features that challenge the app store in future. And it doesn't care who it hurts along the way.

The Mask Is Off

This is exactly what it looks like: a single-fingered salute to the web and web developers. The removal of features that allowed the iPhone to exist at all. The end of Steve Jobs' promise that you'd be able to make great apps out of HTML, CSS, and JS.

For the past few years Apple has gamely sent $1,600/hr lawyers and astroturf lobbyists to argue it didn't need to be regulated. That Apple was really on the developer's side. That even if it overstepped occasionally, it was all in the best interest of users.

Tell that to the millions of EU PWA users about to lose data. Tell that to the public services built on open technology. Tell it to the businesses that will fold, having sweated to deliver compelling experiences using the shite tools Apple provides web developers. Apple's rug pull is anti-user, anti-developer, and anti-competition.

Now we see the whole effort in harsh relief. A web Apple can't sandbag and degrade is one it can't abide. FruitCo's fear and loathing of an open platform it can't tax is palpable. The lies told to cover for avarice are ridiculous — literally, "worthy of ridicule".

It's ok to withhold the benefit of the doubt from Safari and Apple. It's ok to be livid. These lies aren't little or white; they're directly aimed at our future. They're designed to influence the way software will be developed and delivered for decades to come.

If you're as peeved about this as I am, go join OWA in the fight and help them create the sort of pressure in the next 10 days that might actually stop a monopolist with money on their mind.

Thanks to Stuart Langride, Bruce Lawson, and Roderick Gadellaa for their feedback on drafts of this post.

The Performance Inequality Gap, 2024

The global device and network situation continues to evolve, and this series is an effort to provide an an up-to-date understanding for working web developers. So what's changed since last year? And how much HTML, CSS, and (particularly) JavaScript can a new project afford?

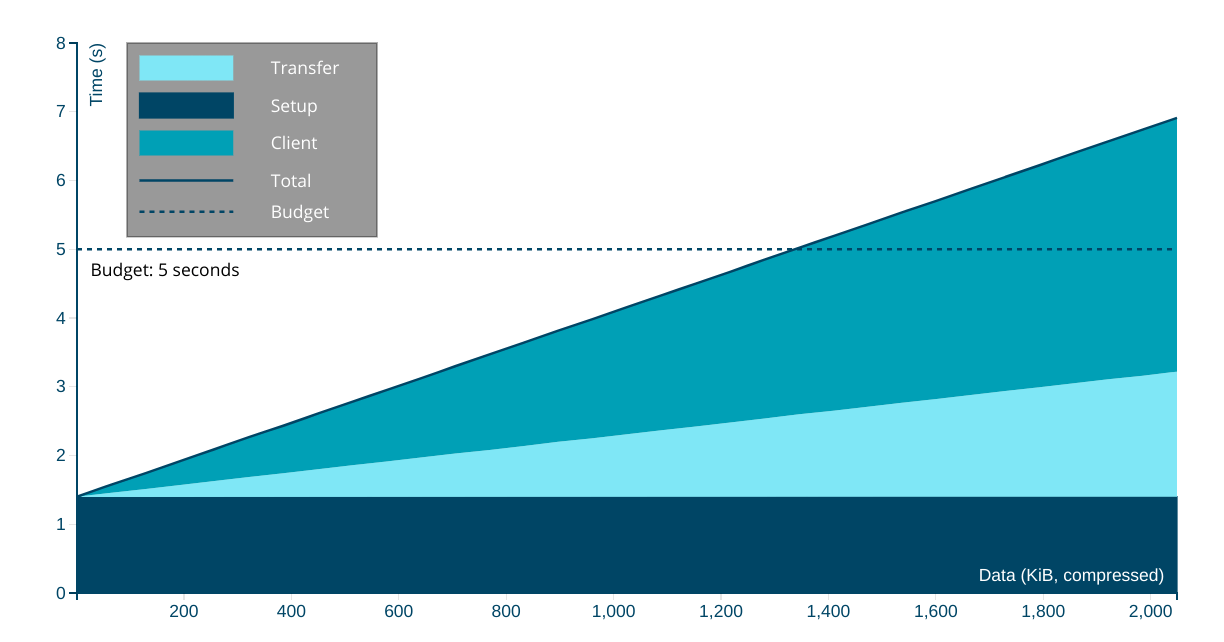

The Budget, 2024

In a departure from previous years, two sets of baseline numbers are presented for first-load under five seconds on 75th (P75) percentile devices and networks1; one set for JavaScript-heavy content, and another for markup-centric stacks.

| Budget @ P75 | Markup-based | JS-based | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Markup | JS | Total | Markup | JS | |

| 3 seconds | 1.4MiB | 1.3MiB | 75KiB | 730KiB | 365KiB | 365KiB |

| 5 seconds | 2.5MiB | 2.4MiB | 100KiB | 1.3MiB | 650KiB | 650KiB |

This was data was available via last year's update, but was somewhat buried. Going forward, I'll produce both as top-line guidance. The usual caveats apply:

- Performance is a deep and nuanced domain, and much can go wrong beyond content size and composition.

- How sites manage resources after-load can have a big impact on perceived performance.

- Your audience may justify more stringent, or more relaxed, limits.

Global baselines matter because many teams have low performance management maturity, and today's popular frameworks – including some that market performance as a feature – fail to ward against catastrophic results.

Until and unless teams have better data about their audience, the global baseline budget should be enforced.

This isn't charity; it's how products stay functional, accessible, and reliable in a market awash in bullshit. Limits help teams steer away from complexity and towards tools that generate simpler output that's easier to manage and repair.

JavaScript-Heavy

Since at least 2015, building JavaScript-first websites has been a predictably terrible idea, yet most of the sites I trace on a daily basis remain mired in script.2 For these sites, we have to factor in the heavy cost of running JavaScript on the client when describing how much content we can afford.

HTML, CSS, images, and fonts can all be parsed and run at near wire speeds on low-end hardware, but JavaScript is at least three times more expensive, byte-for-byte.

Most sites, even those that aspire to be "lived in", are generally experienced through short sessions, which means they can't justify much in the way of up-front code. First impressions always matter.

Targeting the slower of our two representative devices, and opening only two connections over a P75 network, we can afford ~1.3MiB of compressed content to get interactive in five seconds. A page fitting this budget can afford:

- 650KiB of HTML, CSS, images, and fonts

- 650KiB of JavaScript

If we set the target a more reasonable three seconds, the budget shrinks to ~730KiB, with no more than 365KiB of compressed JavaScript.

Similarly, if we keep the five second target but open five TLS connections, the budget falls to ~1MiB. Sites trying to load in three seconds but which open five connections can afford only ~460KiB total, leaving only ~230KiB for script.

Markup-Heavy

Sites largely comprised of HTML and CSS can afford a lot more, although CSS complexity and poorly-loaded fonts can still slow things down. Conservatively, to load in five seconds over two connections, we should try to keep content under 2.5MiB, including:

- 2.4MiB of HTML, CSS, images, and fonts, and

- 100KiB of JavaScript.

To hit the three second first-load target, we should aim for a max 1.4MiB transfer, made up of:

- 1.325MiB of HTML, CSS, etc., and

- 75KiB of JavaScript.

These are generous targets. The blog you're reading loads in ~1.2 seconds over a single connection on the target device and network profile. It consumes 120KiB of critical path resources to become interactive, only 8KiB of which is script.

Calculate Your Own

As in years past, you can use the interactive estimator to understand how connections and devices impact budgets. This the tool has been updated to let you select from JavaScript-heavy and JavaScript-light content composition and defaults to the updated network and device baseline (see below).

It's straightforward to understand the number of critical path network connections and to eyeball the content composition from DevTools or WebPageTest. Armed with that information, it's possible to use this estimator to quickly understand what sort of first-load experience users at the margins can expect. Give it a try!

Situation Report

These recommendations are not context-free, and folks can reasonably disagree.

Indeed, many critiques are possible. The five second target first load)1:1 is arbitrary. A sample population comprised of all internet users may be inappropriate for some services (in both directions). A methodology of "informed reckons" leaves much to be desired. The methodological critiques write themselves.

The rest of this post works to present the thinking behind the estimates, both to spark more informed points of departure and to contextualise the low-key freakout taking place as INP begins to put a price on JavaScript externalities.

Another aim of this series is to build empathy. Developers are clearly out of touch with market ground-truth. Building an understanding of the differences in the experiences of the wealthy vs. working-class users can make the privilege bubble's one-way mirror perceptible from the inside.3

Mobile

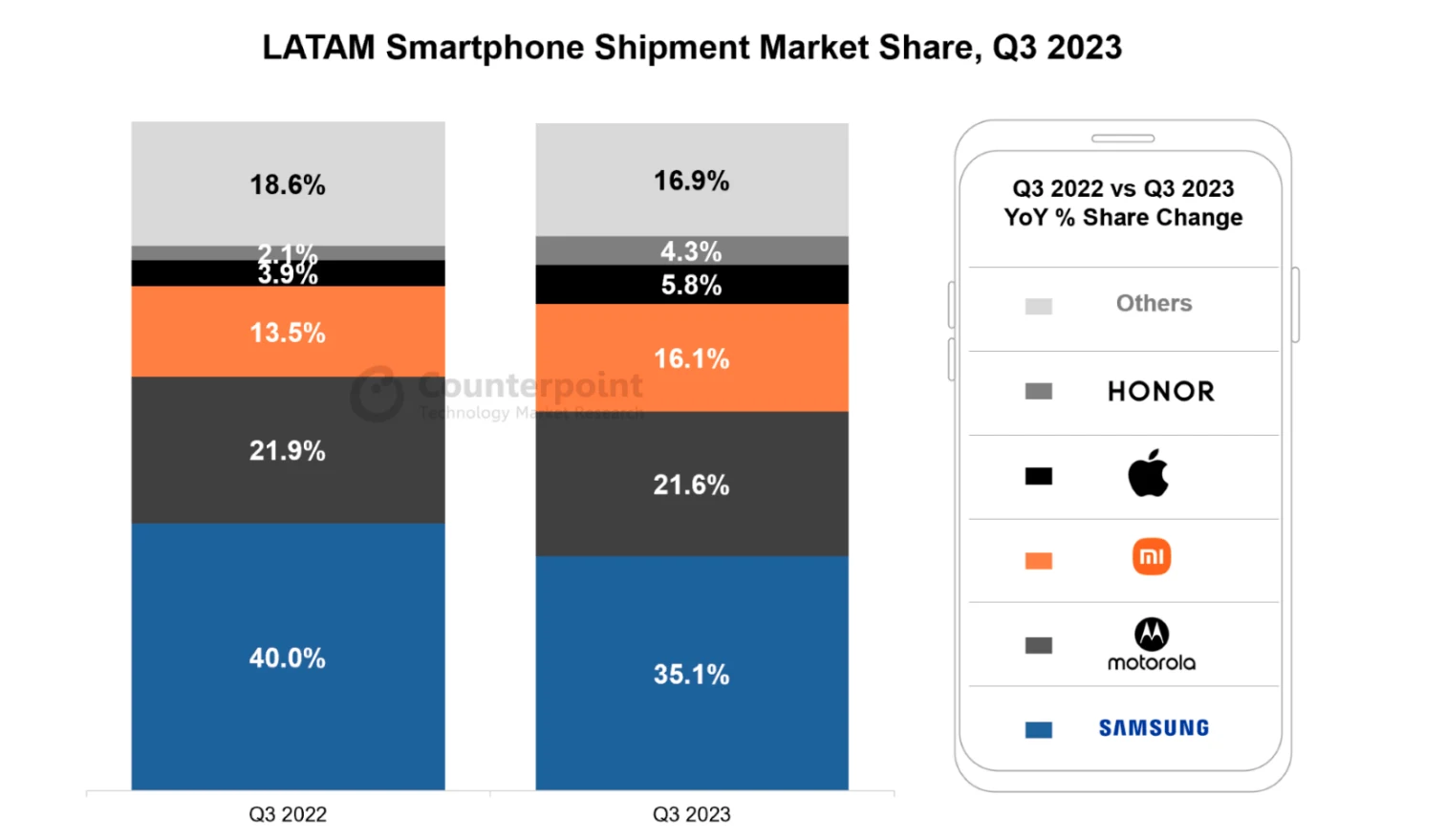

The "i" in iPhone stands for "inequality".

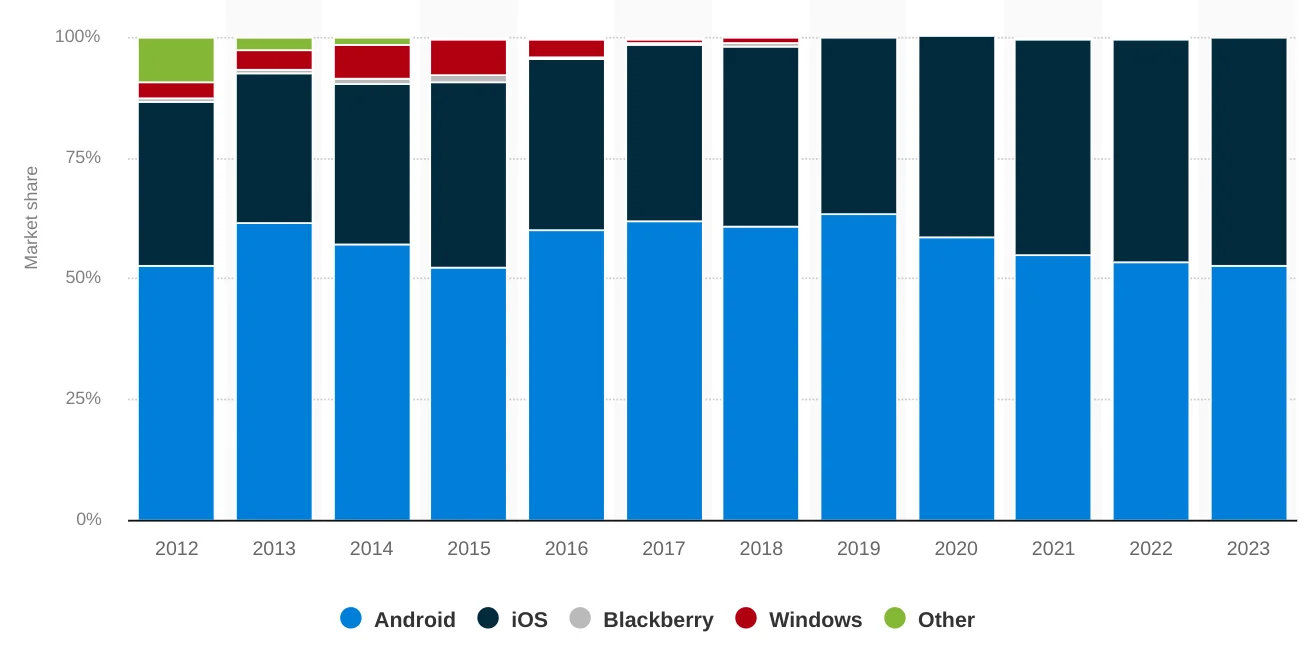

Premium devices are largely absent in markets with billions of users thanks to the chasm of global wealth inequality. India's iOS share has surged to an all-time high of 7% on the back of last-generation and refurbished devices. That's a market of 1.43 billion people where Apple doesn't even crack the top five in terms of shipments.

The Latin American (LATAM) region, home to more than 600 million people and nearly 200 million smartphones, shows a similar market composition:

Everywhere wealth is unequally distributed, the haves read about it in Apple News over 5G while the have-nots struggle to get reliable 4G coverage for their Androids. In country after country (PDF) the embedded inequality of our societies sorts ownership of devices by price. This, in turn, sorts by brand.

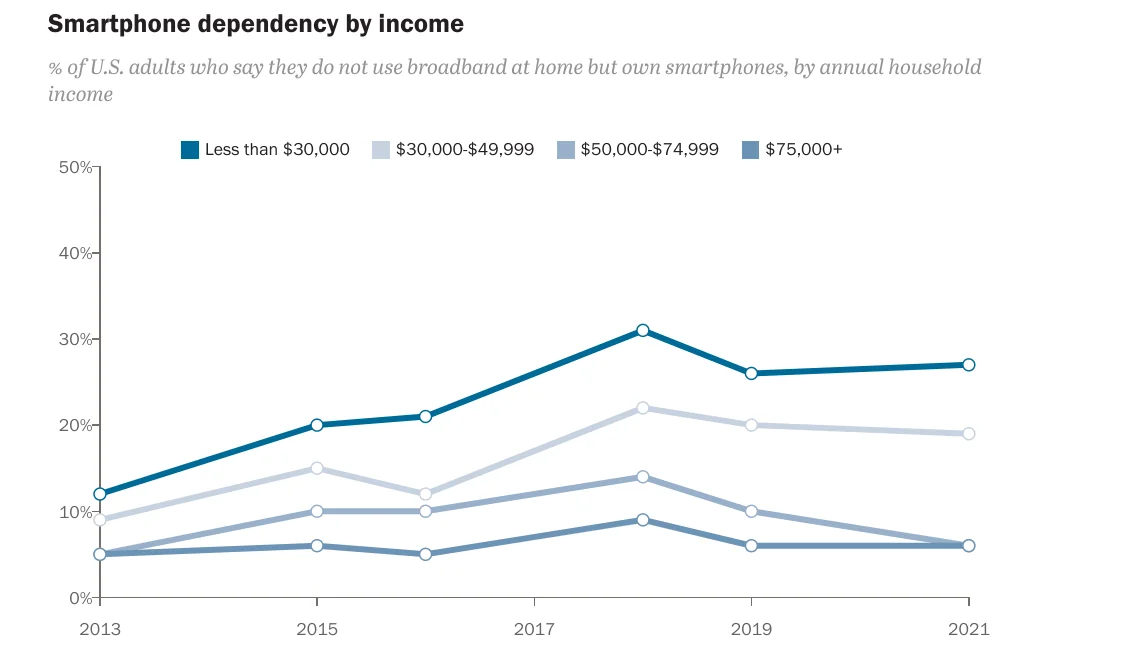

This matters because the properties of devices defines what we can deliver. In the U.S., the term "smartphone dependence" has been coined to describe folks without other ways to access the increasing fraction of essential services only available through the internet. Unsurprisingly, those who can't afford other internet-connected devices, or a fixed broadband subscription, are also likely to buy less expensive smartphones:

As smartphone ownership and use grow, the frontends we deliver remain mediated by the properties of those devices. The inequality between the high-end and low-end is only growing, even in wealthy countries. What we choose to do in response defines what it means to practice UX engineering ethically.

Device Performance

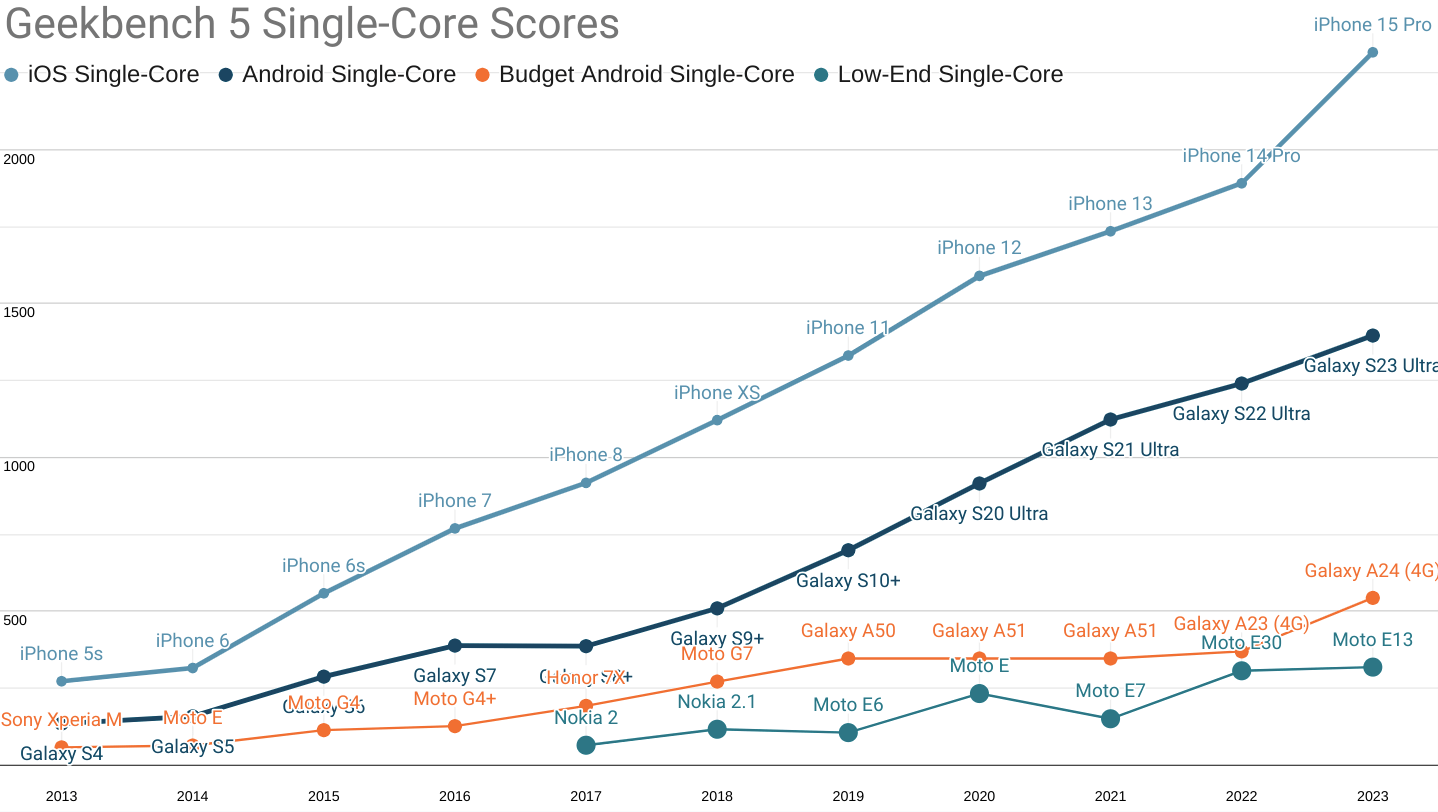

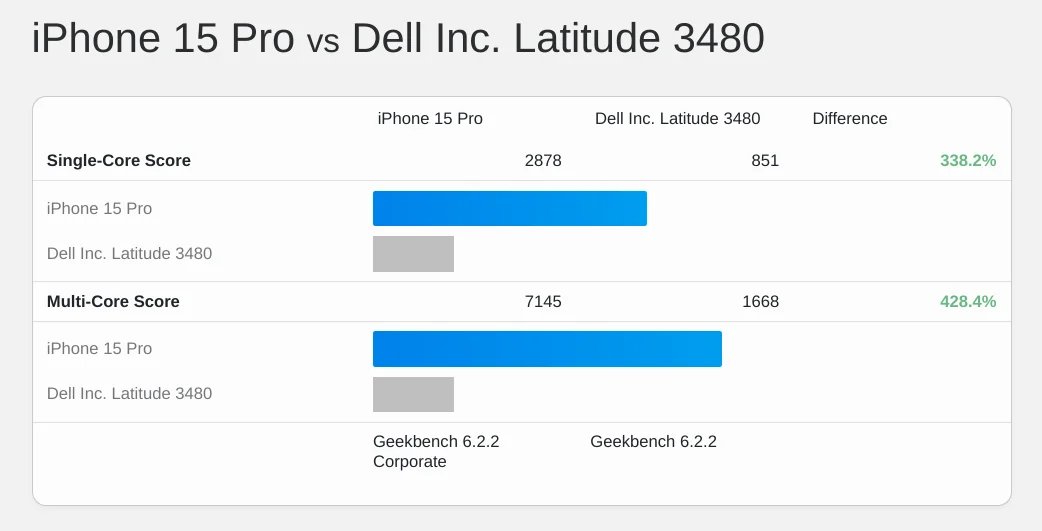

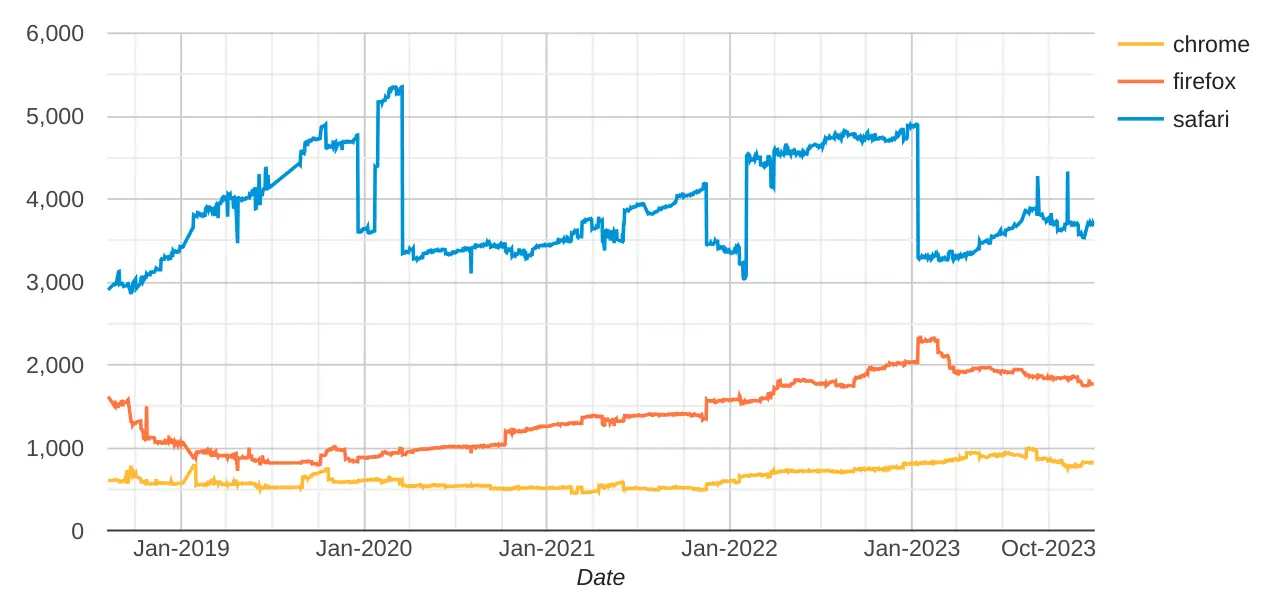

Extending the SoC performance-by-price series with 2023's data, the picture remains ugly:

Geekbench 5 single-core scores for 'fastest iPhone', 'fastest Android', 'budget', and 'low-end' segments.

Not only have fruity phones extended their single-core CPU performance lead over contemporary high-end Androids to a four year advantage, the performance-per-dollar curve remains unfavourable to Android buyers.

At the time of publication, the cheapest iPhone 15 Pro (the only device with the A17 Pro chip) is $999 MSRP, while the S23 (using the Snapdrago 8 gen 2) can be had for $860 from Samsung. This nets out to 2.32 points per dollar for the iPhone, but only 1.6 points per dollar for the S23.

Meanwhile, a $175 (new, unlocked) Samsung A24 scores a more reasonable 3.1 points per dollar on single-core performance, but is more than 4.25× slower than the leading contemporary iPhone.

The delta between the fastest iPhones and moderately price new devices rose from 1,522 points last year to 1,774 today.

Put another way, the performance gap between wealthy users and budget shoppers grew more this year (252 points) than the gains from improved chips delivered at the low end (174 points). Inequality is growing faster than the bottom-end can improve. This is particularly depressing because single-core performance tends to determine the responsiveness of web app workloads.

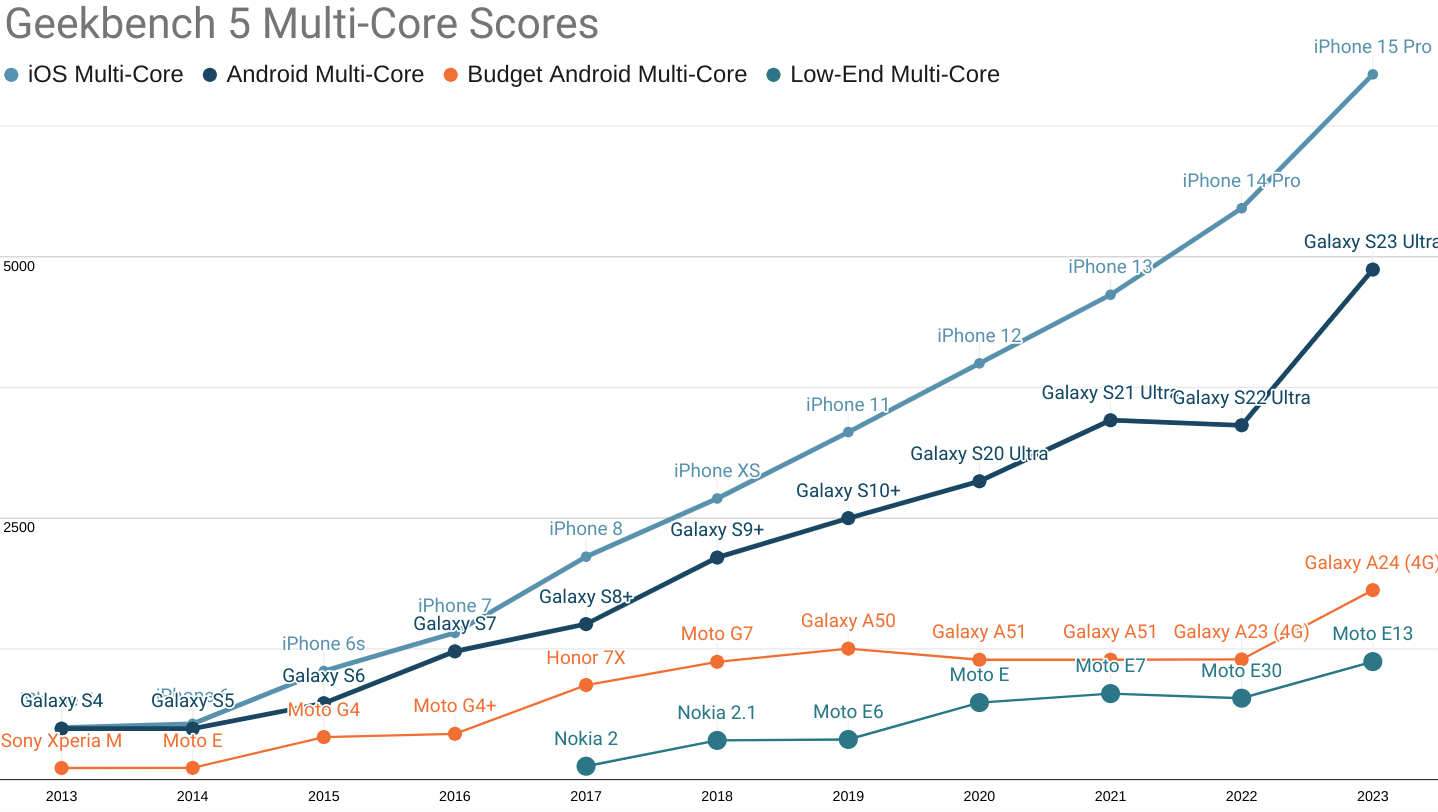

A less pronounced version of the same story continues to play out in multi-core performance:

Round and round we go: Android ecosystem SoCs are improving, but the Performance Inequality Gap continues to grow. Even the fastest Androids are 18 months (or more) behind equivalently priced iOS-ecosystem devices.

Recent advances in high-end Android multi-core performance have closed the previous three-year gap to 18 months. Meanwhile, budget segment devices have finally started to see improvement (as this series predicted), thanks to hand-me-down architecture and process node improvements. That's where the good news ends.

The multi-core performance gap between i-devices and budget Androids grew considerably, with the score delta rising from 4,318 points last year to 4,936 points in 2023.

Looking forward, we can expect high-end Androids to at least stop falling further behind owing to a new focus on performance by Qualcomm's Snapdragon 8 gen 3 and MediaTek's Dimensity 9300 offerings. This change is long, long overdue and will take years to filter down into positive outcomes for the rest of the ecosystem. Until that happens, the gap in experience for the wealthy versus the rest will not close.

iPhone owners experience a different world than high-end Android buyers, and live galaxies apart from the bulk of the market. No matter how you slice it, the performance inequality gap is growing for CPU-bound workloads like JavaScript-heavy web apps.

Networks

As ever, 2023 re-confirmed an essential product truth: when experiences are slow, users engage less. Doing a good job in an uneven network environment requires thinking about connection availability and engineering for resilience. It's always better to avoid testing the radio gods than spend weeks or months appeasing them after the damage is done.

5G network deployment continues apace, but as with the arrival of 4G, it is happening unevenly and in ways and places that exacerbate (rather than lessen) performance inequality.4

Data on mobile network evolution is sketchy,5 and the largest error bars in this series' analysis continue to reside in this section. Regardless, we can look industry summaries like the GSMA's report on "The Mobile Economy 2023" (PDF) for a directional understanding that we can triangulate with other data points to develop a strong intuition.

For instance, GSMA predicts that 5G will only comprise half of connections by 2030. Meanwhile, McKinsey predicts that high-quality 5G (networks that use 6GHz bands) will only cover a quarter of the world's population by 2030. Regulatory roadblocks are still being cleared.

As we said in 2021, "4G is a miracle, 5G is a mirage."

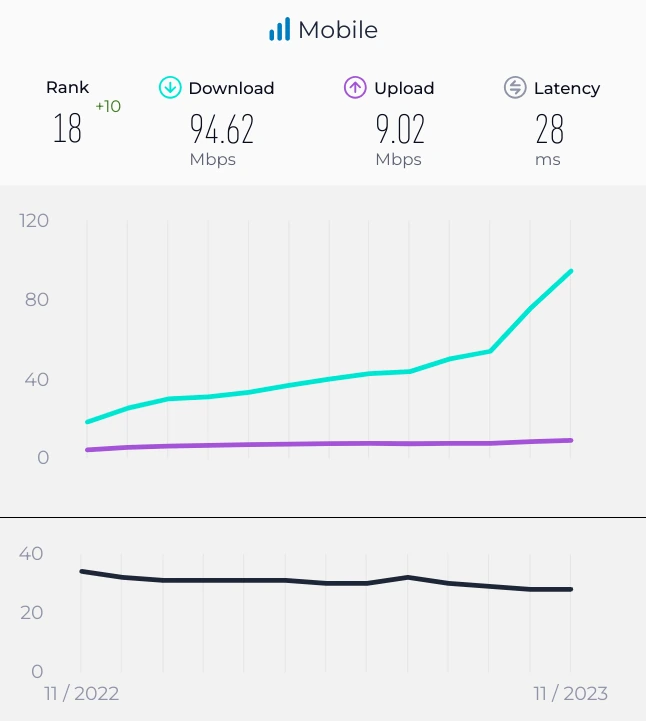

This doesn't mean that 4G is one thing, or that it's deployed evenly, or even that the available spectrum will remain stable within a single generation of radio technology. For example, India's network environment has continued to evolve since the Reliance Jio revolution that drove 4G into the mainstream and pushed the price of a mobile megabyte down by ~90% on every subcontinental carrier.

Speedtest.net's recent data shows dramatic gains, for example, and analysts credit this to improved infrastructure density, expanded spectrum, and back-haul improvements related to the 5G rollout — 4G users are getting better experiences than they did last year because of 5G's role in reducing contention.

These gains are easy to miss looking only at headline "4G vs. 5G" coverage. Improvements arrive unevenly, with the "big" story unfolding slowly. These effects reward us for looking at P75+, not just means or medians, and intentionally updating priors on a regular basis.

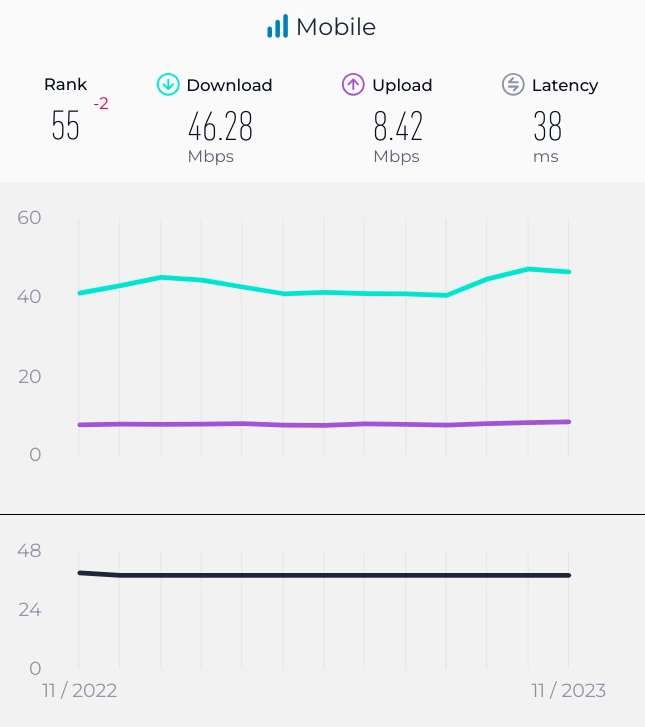

Events can turn our intuitions on their heads, too. Japan is famously well connected. I've personally experienced rock-solid 4G through entire Tokyo subway journeys, more than 40m underground and with no hiccups. And yet, the network environment has been largely unchanged by the introduction of 5G. Having provisioned more than adequately in the 4G era, new technology isn't having the same impact from pent-up demand. But despite consistent performance, the quality of service for all users is distributed in a much more egalitarian way:

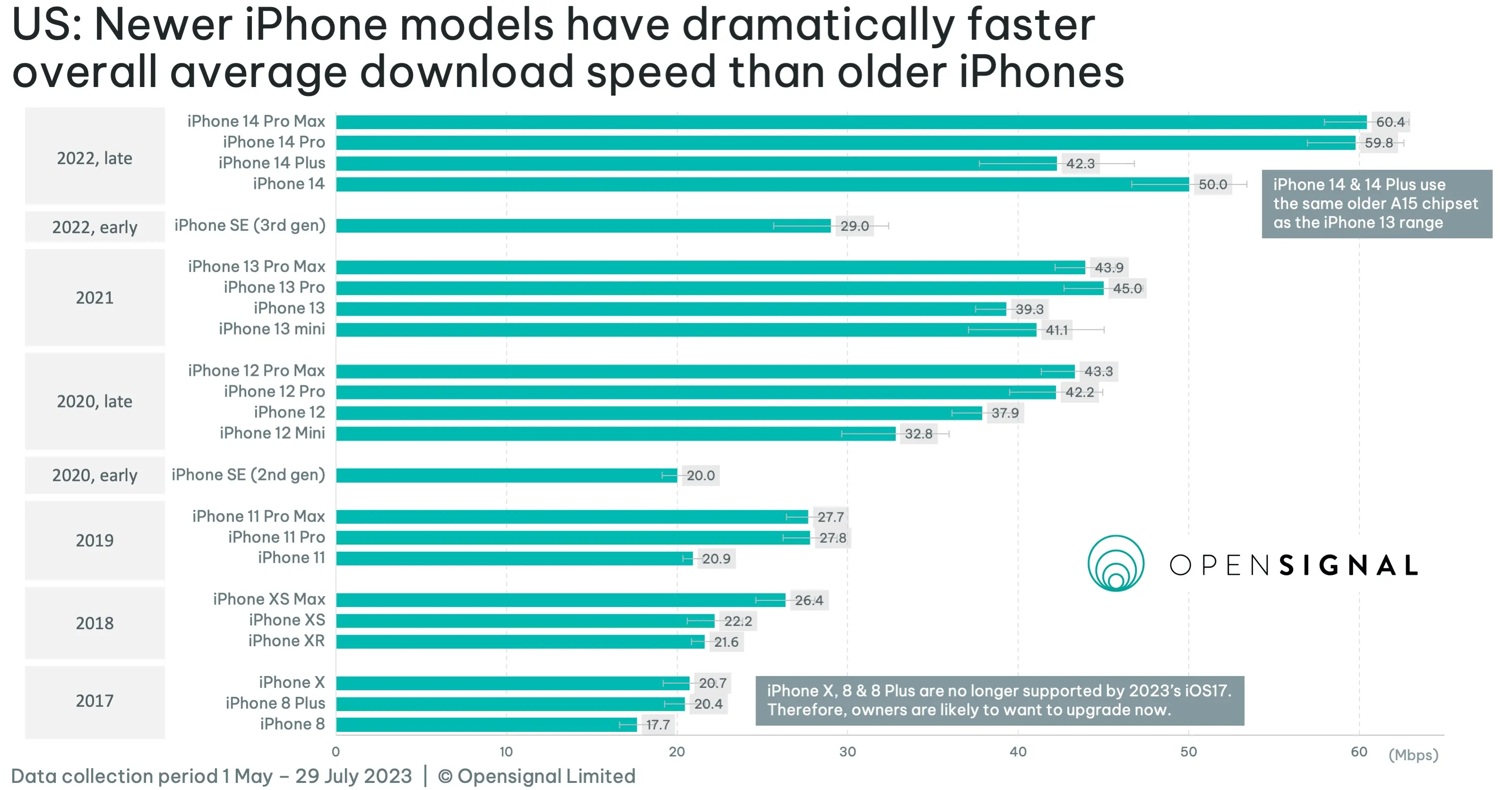

Fleet device composition has big effects, owing to differences in signal-processing compute availability and spectrum compatibility. At a population level, these influences play out slowly as devices age out, but still have impressively positive impacts:

As inequality grows, averages and "generation" tags can become illusory and misleading. Our own experiences are no guide; we've got to keep our hands in the data to understand the texture of the world.

So, with all of that as prelude, what can we say about where the mobile network baseline should be set? In a departure from years prior, I'm going to use a unified network estimate (see below). You'll have to read on for what it is! But it won't be based on the sort of numbers that folks explicitly running speed tests see; those aren't real life.

Market Factors

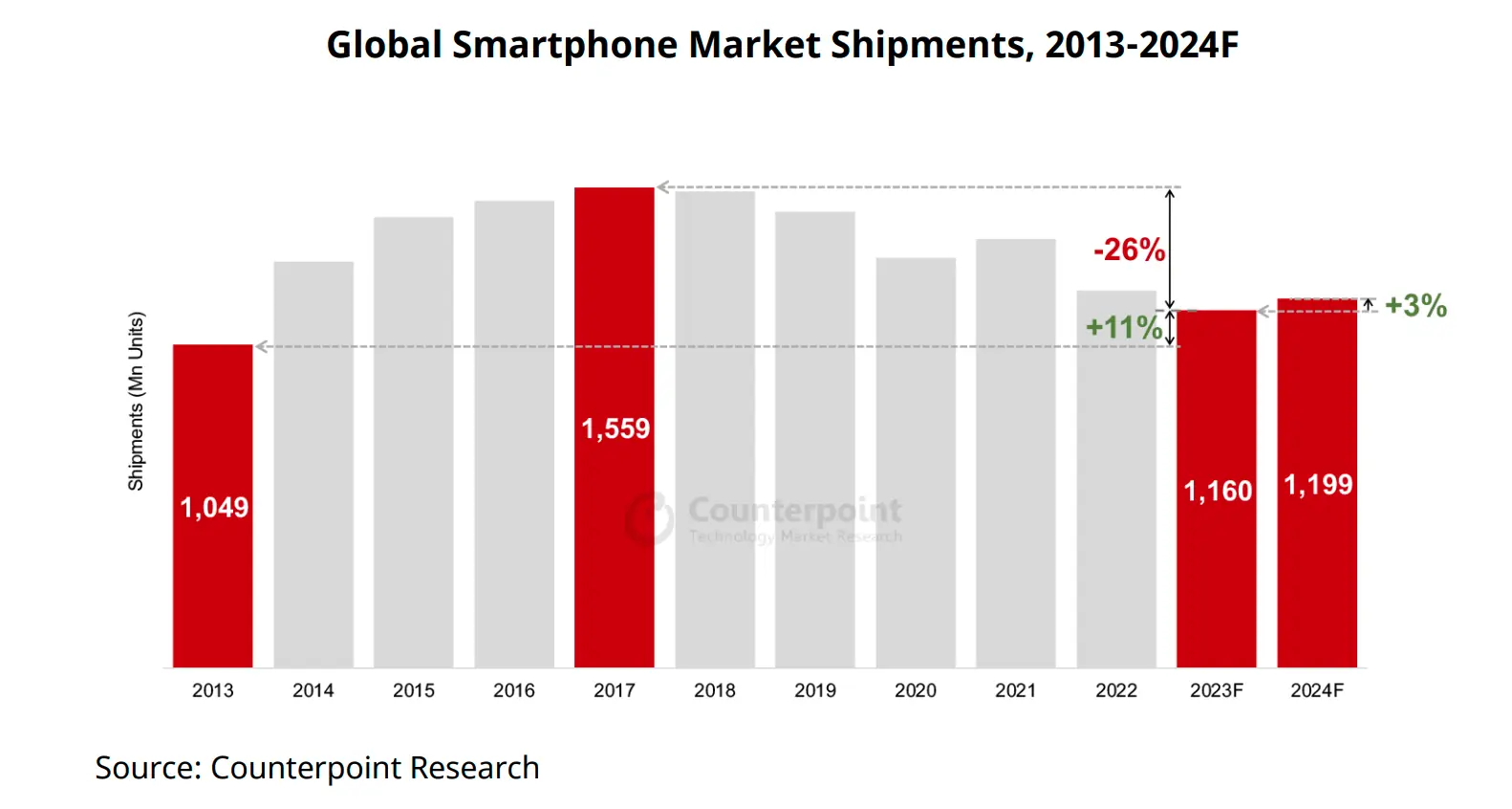

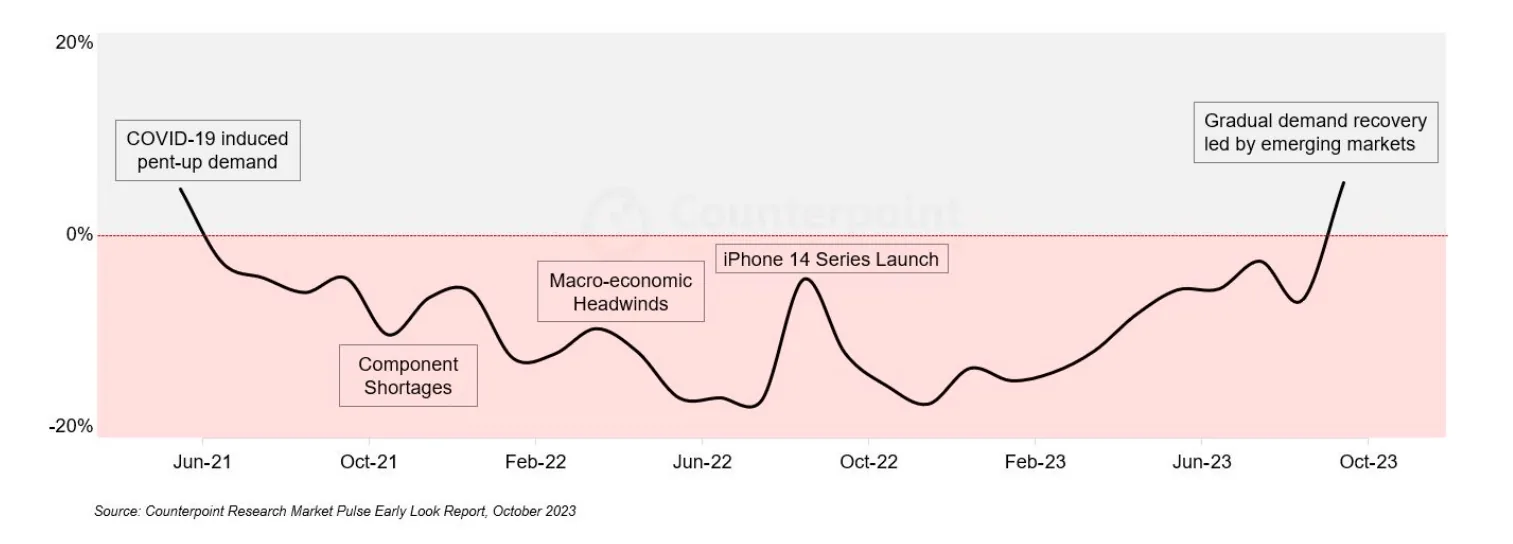

The market forces this series previewed in 2017 have played out in roughly a straight line: smartphone penetration in emerging markets is approaching saturation, ensuring a growing fraction of purchases are made by upgrade shoppers. Those who upgrade see more value in their phones and save to buy better second and third devices. Combined with the emergence and growth of the "ultra premium" segment, average selling prices (ASPs) have risen.

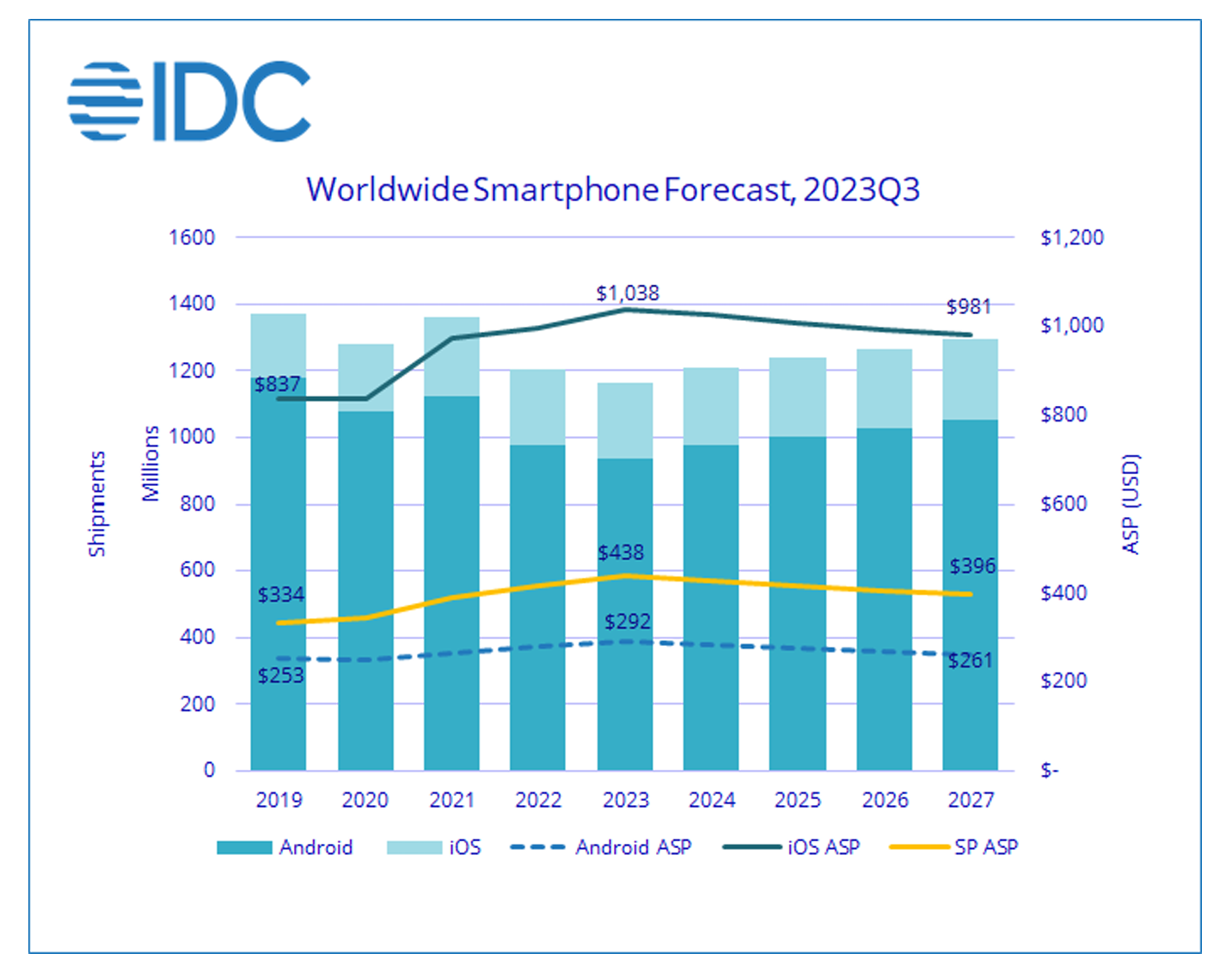

2022 and 2023 have established an inflection point in the regard, with worldwide average selling prices jumping to more than $430, up from $300-$350 for much of the decade prior. Some price appreciation has been due to transient impacts of the U.S./China trade wars, but most of it appears driven by iOS ASPs which peaked above $1,000 for the first time in 2023. Android ASPs, meanwhile, continued a gradual rise to nearly $300, up from $250 five years ago.

A weak market for handsets in 2023, plus stable sales for iOS, had an notable impact on prices. IDC expects global average prices to fall back below $400 by 2027 as Android volumes increase from an unusually soft 2023.

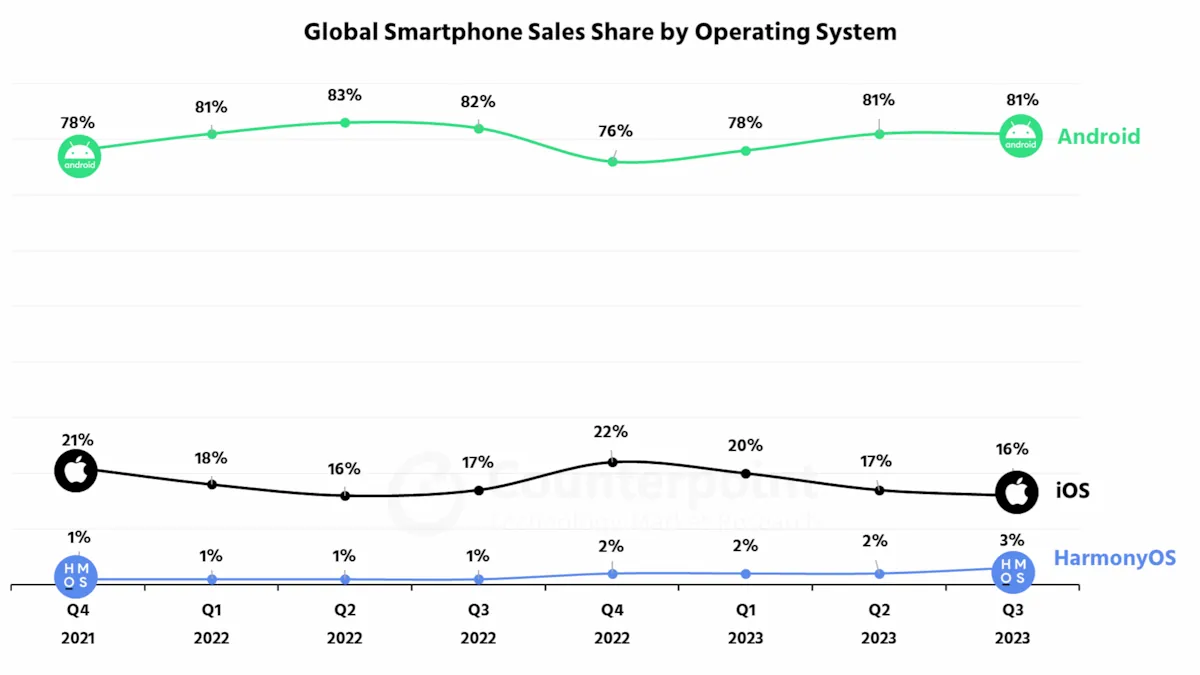

Despite falling sales, distribution of Android versus iOS sales remains largely unchanged:

Smartphone replacement rates have remained roughly in line with previous years, although we should expect higher device longevity in future years. Survey reports and market analysts continue to estimate average replacement at 3-4 years, depending on segment. Premium devices last longer, and a higher fraction of devices may be older in wealthy geographies. Combined with discretionary spending pressure and inflationary impacts on household budgets, consumer intent to spend on electronics has taken a hit, which will be felt in device lifetime extension until conditions improve. Increasing demand for refurbished devices also adds to observable device aging.

The data paints a substantially similar picture to previous years: the web is experienced on devices that are slower and older than those carried by affluent developers and corporate directors whose purchasing decisions are not impacted by transitory inflation.

To serve users effectively, we must do extra work to live as our customers do.

Test Device Recommendations

Re-using last year's P75 device calculus, our estimate is based on a device sold new, unlocked for the mid-2020 to mid-2021 global ASP of ~$350-375.

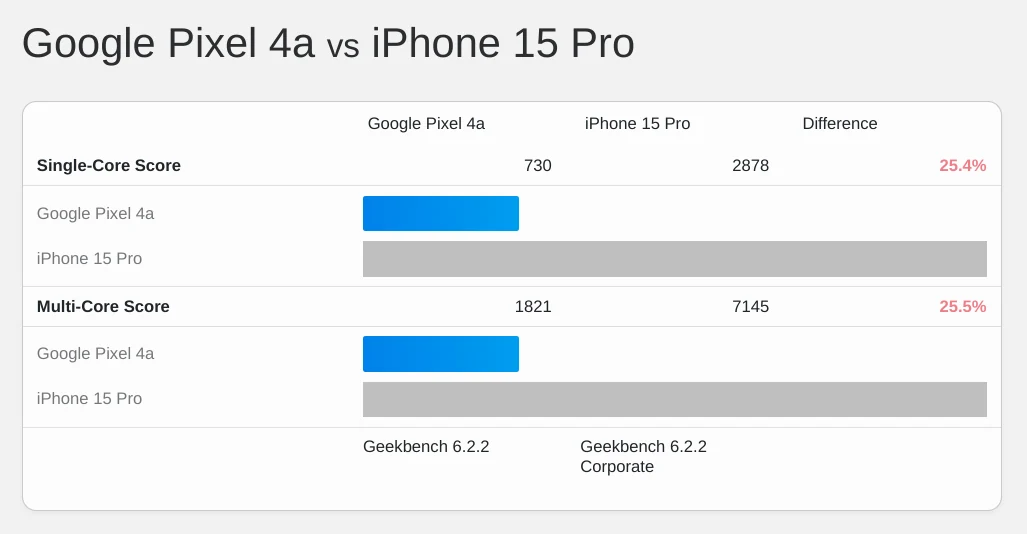

Representative examples from that time period include the Samsung Galaxy A51 and the Pixel 4a. Neither model featured 5G,6 and we cannot expect 5G to play a significant role in worldwide baselines for at least the next several years.4:1

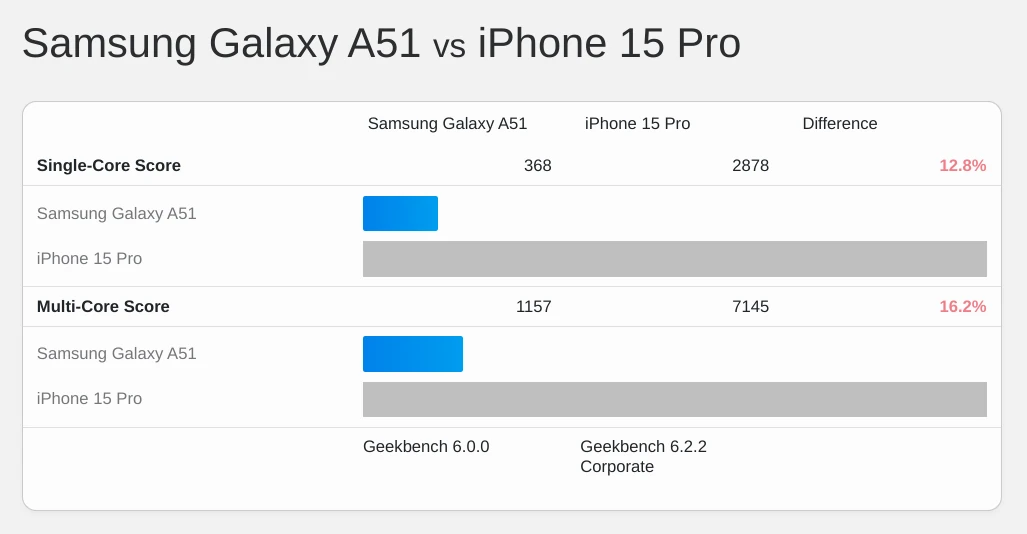

The A51 featured eight slow cores (4x2.3 GHz Cortex-A73 and 4x1.7 GHz Cortex-A53) on a 10nm process:

The Pixel 4a's slow, eight-core big.LITTLE configuration was fabricated on an 8nm process:

Pixels have never sold well, and Google's focus on strong >SoC performance per dollar was sadly not replicated across the Android ecosystem, forcing us to use the A51 as our stand-in.

Devices within the envelope of our attention are 15-25% as fast as those carried by programmers and their bosses — even in wealthy markets.

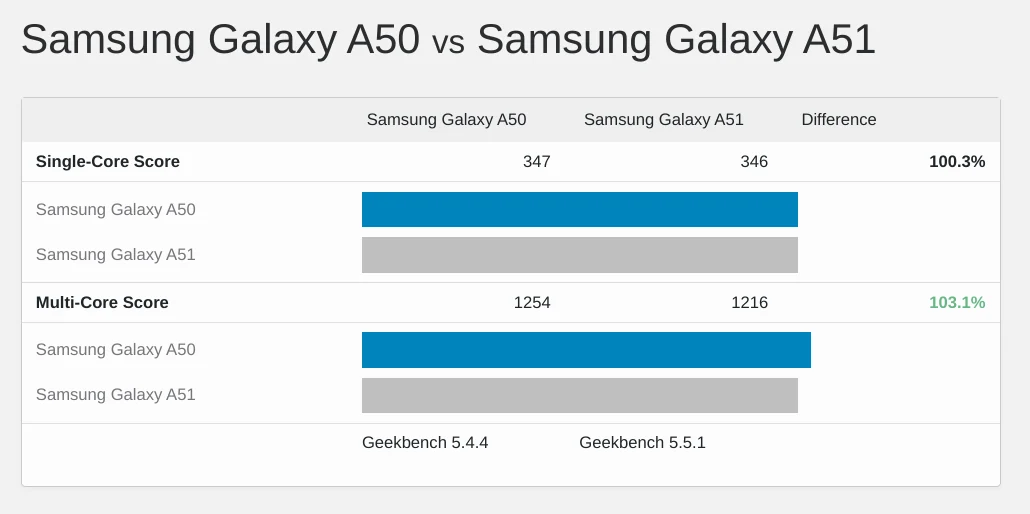

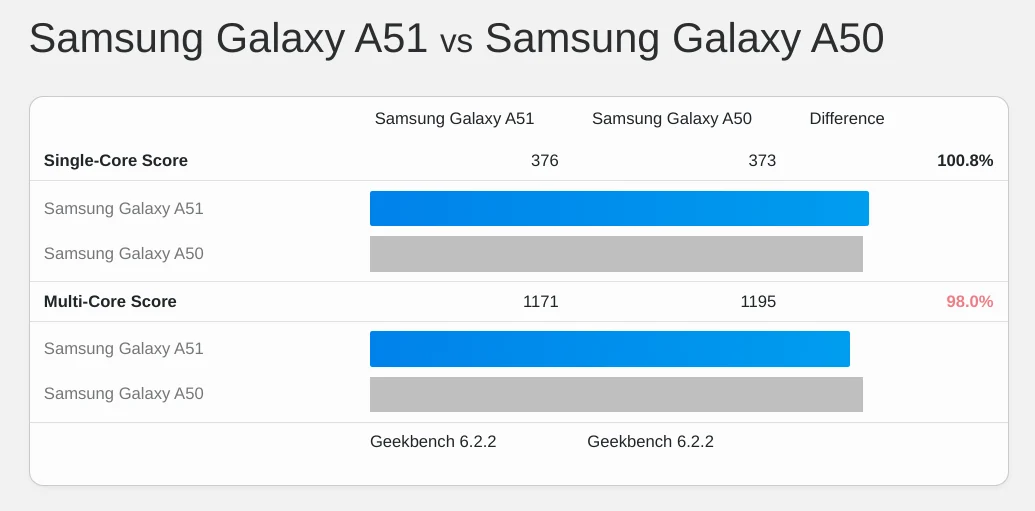

The Galaxy may be slightly faster than last year's recommendation of the Galaxy A50 for testing, but the picture is muddy:

If you're building a test lab today, refurbished A51s can be had for ~$150. Even better, the newer Nokia G100 can be had for as little as $100, and it's faithful to the sluggish original in nearly every respect.7

If your test bench is based on last year's recommended A50 or Nokia G11, I do not recommend upgrading in 2024. The absolute gains are so slight that the difference will be hard to feel, and bench stability has a value all its own. Looking forward, we can also predict that our bench performance will be stable until 2025.

Claims about how "performant" modern frontend tools are have to be evaluated in this slow, stagnant context.

Desktop

It's a bit easier to understand the Desktop situation because the Edge telemetry I have access to provides statistically significant insight into 85+% of the market.

Device Performance

The TL;DR for desktop performance is that Edge telemetry puts ~45% of devices in a "low-end" bucket, meaning they have <= 4 cores or <= 4GB of RAM.

| Device Tier | Fleet % | Definition |

| Low-end | 45% | Either: <= 4 cores, or <= 4GB RAM |

| Medium | 48% | HDD (not SSD), or 4-16 GB RAM, or 4-8 cores |

| High | 7% | SSD + > 8 cores + > 16GB RAM |

20% of users are on HDDs (not SSDs) and nearly all of those users also have low (and slow) cores.

You might be tempted to dismiss this data because it doesn't include Macs, which are faster than the PC cohort. Recall, however, that the snapshot also excludes ChromeOS.

ChromeOS share has veered wildly in recent years, representing 50%-200% of Mac shipments in a given per quarter. In '21 and '22, ChromeOS shipments regularly doubled Mac sales. Despite post-pandemic mean reversion, according to IDC ChromeOS devices outsold Macs ~5.7M to ~4.7M in 2023 Q2. The trend reversed in Q3, with Macs almost doubling ChromeOS sales, but slow ChromeOS devices aren't going away and, from a population perspective, more than offset Macs today. Analysts also predict growth in the low end of the market as educational institutions begin to refresh their past purchases.

Networks

Desktop-attached networks continue to improve, notably in the U.S. Regulatory intervention and subsidies have done much to spur enhancements in access to U.S. fixed broadband, although disparities in access remain and the gains may not persist.

This suggests that it's time to also bump our baseline for desktop tests beyond the 5Mbps/1Mbps/28ms configuration that WebPageTest.org's "Cable" profile has defaulted to for desktop tests.

How far should we bump it? Publicly available data is unclear, and I've come to find out that Edge's telemetry lacks good network observation statistics (doh!).

But the comedy of omissions doesn't end there: Windows telemetry doesn't capture a proxy for network quality, I no longer have access to Chrome's data, the population-level telemetry available from CrUX is unhelpful, and telcos li...er...sorry, "market their products in accordance with local laws and advertising standards."

All of this makes it difficult to construct an estimate.

One option is to use a population-level assessment of medians from something like the Speedtest.net data and then construct a histogram from median speeds. This is both time-consuming and error-prone, as population-level data varies widely across the world. Emerging markets with high mobile internet use and dense populations can feature poor fixed-line broadband penetration compared with Western markets.

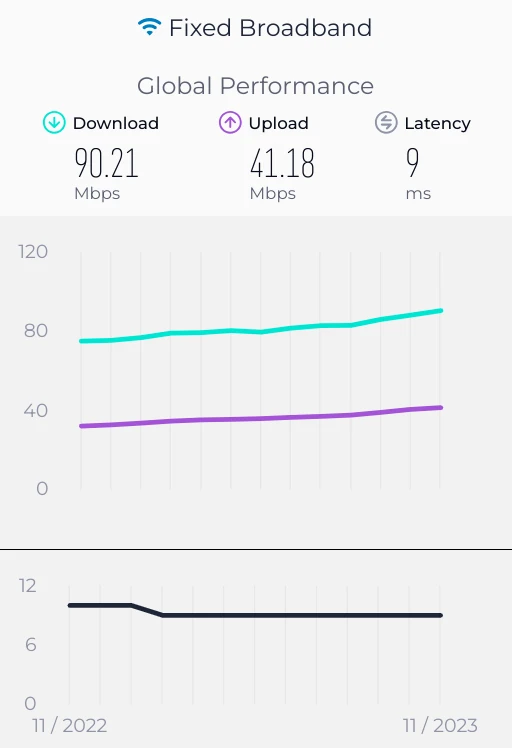

Another option is to mathematically hand-wave using the best evidence we can get. This might allow us to reconstruct probable P75 and P90 values if we know something about the historical distribution of connections. From there, we can gut-check using other spot data. To do this, we need to assume some data set is representative, a fraught decision all its own.8 Biting the bullet, we could start from the Speedtest.net global survey data, which currently fails to provide anything but medians (P50):

After many attempted Stupid Math Tricks with poorly fitting curves (bandwidth seems to be a funky cousin of log-normal), I've decided to wing it and beg for help: instead of trying to be clever, I'm leaning on Cloudflare Radar's P25/P50/P75 distributions for populous, openly-connected countries with >= ~50M internet users. It's cheeky, but a weighted average of the P75 of download speeds (3/4ths of all connections are faster) should get us in the ballpark. We can then use the usual 5:1 downlink:uplink ratio to come up with an uplink estimate. We can also derive a weighted average for the P75 RTT from Cloudflare's data. Because Cloudflare doesn't distinguish mobile from desktop connections, this may be an overly conservative estimate, but it's still be more permissive than what we had been pegged to in years past:

| Country | P75 Downlink (Mbps) | P75 RTT (ms) |

| India | 4 | 114 |

| USA | 11 | 58 |

| Indonesia | 5 | 81 |

| Brazil | 8 | 71 |

| Nigeria | 3 | 201 |

| Pakistan | 3 | 166 |

| Bangladesh | 5 | 114 |

| Japan | 17 | 42 |

| Mexico | 7 | 75 |

| Egypt | 4 | 100 |

| Germany | 16 | 36 |

| Turkey | 7 | 74 |

| Philippines | 7 | 72 |

| Vietnam | 7 | 72 |

| United Kingdom | 16 | 37 |

| South Korea | 24 | 26 |

| Population Weighted Avg. | 7.2 | 94 |

We, therefore, update our P75 link estimate 7.2Mbps down, 1.4Mbps up, and 94ms RTT.

This is a mild crime against statistics, not least of all because it averages unlike quantities and fails to sift mobile from desktop, but all the other methods available at time of writing are just as bad. Regardless, this new baseline is half again as much link capacity as last year, showing measurable improvement in networks worldwide.

If you or your company are able to generate a credible worldwide latency estimate in the higher percentiles for next year's update, please get in touch.

Market Factors

The forces that shape the PC population have been largely fixed for many years. Since 2010, volumes have been on a slow downward glide path, shrinking from ~350MM per year in a decade ago to ~260MM in 2018. The pandemic buying spree of 2021 pushed volumes above 300MM per year for the first time in eight years, with the vast majority of those devices being sold at low-end price points — think ~$300 Chromebooks rather than M1 MacBooks.

Lest we assume low-end means "short-lived", recent announcements regarding software support for these devices will considerably extend their impact. This low-end cohort will filter through the device population for years to come, pulling our performance budgets down, even as renewed process improvement is unlocking improved power efficiency and performance at the high end of the first-sale market. This won't be as pronounced as the diffusion of $100 smartphones has been in emerging markets, but the longer life-span of desktops is already a factor in our model.

Test Device Recommendations

Per our methodology from last year which uses the 5-8 year replacement cycle for a PC, we update our target date to late 2017 or early 2018, but leave the average-selling-price fixed between $600-700. Eventually we'll need to factor in the past couple of years of gyrations in inflation and supply chains into account when making an estimate, but not this year.

So what did $650, give or take, buy in late 2017 or early 2018?

One option was a naf looking tower from Dell, optimistically pitched at gamers, with a CPU that scores poorly versus a modern phone, but blessedly includes 8GB of RAM.

In laptops (the larger segment), ~$650 bought the Lenovo Yoga 720 (12"), with a 2-core (4-thread) Core i3-7100U and 4GB of RAM. Versions with more RAM and a faster chip were available, but cost considerably more than our budget. This was not a fast box. Here's a device with that CPU compared to a modern phone; not pretty:

It's considerably faster than some devices still being sold to schools, though.

What does this mean for our target devices? There's wild variation in performance per dollar below $600 which will only increase as inflation-affected cohorts grow to represent a larger fraction of the fleet. Intel's move off of 14nm (finally!) also means that gains are starting to arrive at the low end, but in an uneven way. General advice is therefore hard to issue. That said, we can triangulate based on what we know about the market:

- Most PCs are laptops or tablets. This means they're power-limited.

- Most devices are more than four years old.

- Conservative estimates are future-proof.

My recommendation, then, to someone setting up a new lab today is not to spend more than $350 on new a test device. Consider laptops with chips like the N4120, N4500, or the N5105. Test devices should also have no more than 8GB of RAM, and preferably 4GB. The 2021 HP 14 is a fine proxy. The updated ~$375 version will do in a pinch, but try to spend less if you can. Test devices should preferably score no higher than 1,000 in single-core Geekbench 6 tests; a line the HP 14's N4120 easily ducks, clocking in at just over 350.

Takeaways

There's a lot of good news embedded in this year's update. Devices and networks have finally started to get faster (as predicted), pulling budgets upwards.

At the same time, the community remains in denial about the disastrous consequences of an over-reliance on JavaScript. This paints a picture of path dependence — frontend isn't moving on from approaches that hurt users, even as the costs shift back onto teams that have been degrading life for users at the margins.

We can anticipate continued improvement in devices, while network gains will level out as the uneven deployment of 5G stumbles forward. Regardless, the gap between the digital haves and have-nots continues to grow. Those least able to afford fast devices are suffering regressive taxation from developers high on DX fumes.

It's no mystery why folks in the privilege bubble are not building with empathy or humility when nobody calls them to account. What's mysterious is that anybody pays them to do it.

The PM and EM disciplines have utterly failed, neglecting to put business constraints on the enthusiasms of developers. This burden is falling, instead, on users and their browsers. Browsers have had to step in as the experience guardians of last resort, indicating a market-wide botching of the job in technology management ranks and an industry-scale principal-agent issue amongst developers.

Instead of cabining the FP crowd's proclivities for the benefit of the business, managers meekly repeat bullshit like "you can't hire for fundamentals" while bussing in loads of React bootcampers. It is not too much to ask that managers run bake-offs and hire for skills in platform fundamentals that serve businesses better over time. The alternative is continued failure, even for fellow privilege bubble dwellers.

Case in point: this post was partially drafted on airplane wifi, and I can assure you that wealthy folks also experience RTTs north of 500ms and channel capacity in the single-digit-Mbps.

Even the wealthiest users step into the wider world sometimes. Are these EMs and PMs really happy to lose that business?

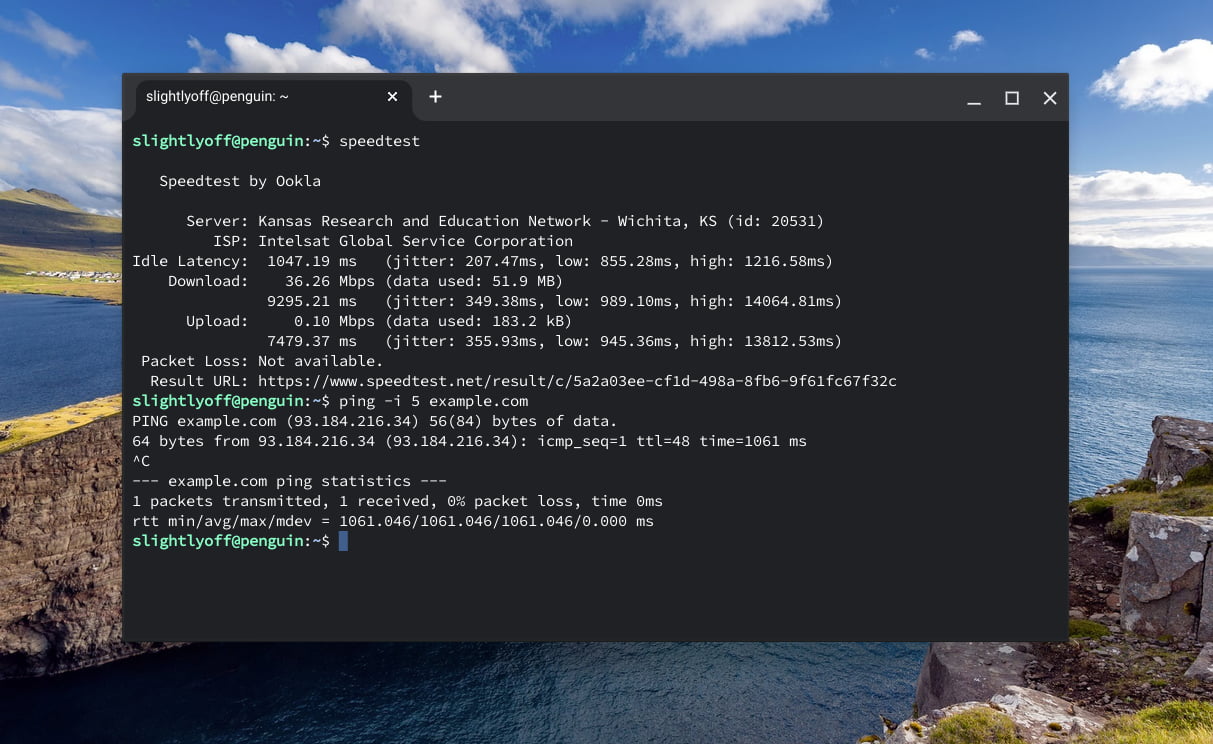

Wealthy users are going to experience networks with properties that are even worse than the 'bad' networks offered to the Next Billion Users. At an altitude of 40k feet and a ground speed for 580 MPH somewhere over Alberta, CA, your correspondent's bandwidth is scarce, lopsided, and laggy.

Of course, any trend that can't continue won't, and INP's impact is already being felt. The great JavaScript merry-go-round may grind to a stop, but the momentum of consistently bad choices is formidable. Like passengers on a cruise ship ramming a boardwalk at flank speed, JavaScript regret is dawning far too late. As the good ship Scripting shudders and lists on the remains of the ferris wheel, it's not exactly clear how to get off, but the choices that led us here are becoming visible, if only through their negative consequences.

The Great Branch Mispredict

We got to a place where performance has been a constant problem in large part because a tribe of programmers convinced themselves that it wasn't and wouldn't be. The circa '13 narrative asserted that:

- CPUs would keep getting faster (just like they always had).

- Networks would get better, or at least not get worse.

- Organisations had all learned the lessons of Google and Facebook's adventures in Ajax.

It was all bullshit, and many of us spotted it a mile away.

The problem is now visible and demands a solution, but the answers will be largely social, not technical. User-centered values must contest the airtime previouly taken by failed trickle-down DX mantras. Only when the dominant story changes will better architectures and tools win.

How deep was the branch? And how many cycles will the fault cost us? If CPUs and networks continue to improve at the rate of the past two years, and INP finally forces a reckoning, the answer might be as little as a decade. I fear we will not be so lucky; an entire generation has been trained to ignore reality, to prize tribalism rather than engineering rigor, and to devalue fundamentals. Those folks may not find the next couple of years to their liking.

Frontend's hangover from the JavaScript party is gonna suck.

FOOTNOTES

The five second first-load target is arbitrary, and has always been higher than I would prefer. Five seconds on a modern computer is an eternity, but in 2016 I was talked down from my preferred three-second target by Googlers that despaired that "nobody" could hit that mark on the devices and networks of that era.

This series continues to report budgets with that target, but keen readers will see that I'm also providing three-second numbers. The interactive estimation tool was also updated this year to provides the ability to configure the budget target.

If you've got thoughts about how this should be set in future, or how it could be handled better, plesae get in touch. ⇐ ⇐

Frontend developers are cursed to program The Devil's Computer. Web apps execute on slow devices we don't spec or provision, on runtimes we can barely reason about, lashed to disks and OSes taxed by malware and equally invasive security software, over networks with the variability of carrier pigeons.

It's vexing, then, that contemporary web development practice has decided that the way to deliver great experiences is to lean into client CPUs and mobile networks, the most unreliable, unscalable properties of any stack.

And yet, here we are in 2024, with Reactors somehow still anointed to decree how and where code should run, despite a decade of failure to predict the obvious, or even adapt to the world as it has been. The mobile web overtook desktop eight years ago, and the best time to call bullshit on JS-first development was when we could first see the trends clearly.

The second best time is now. ⇐

Engineering is design under constraint, with the goal to develop products that serve users and society.

The opposite of engineering is bullshit; substituting fairy tales for inquiry and evidence.

For the frontend to earn and keep its stripes as an engineering discipline, frontenders need to internalise the envelope of what's possible on most devices. ⇐

For at least a decade to come, 5G will continue to deliver unevenly depending on factors including building materials, tower buildout, supported frequencies, device density, radio processing power, and weather. Yes, weather (PDF).

Even with all of those caveats, 5G networks aren't the limiting factor in wealthy geographies; devices are. It will take years for the deployed base to be fully replaced with 5G-capable handsets, and we should expect the diffusion to be "lumpy", with wealthy markets seeing 5G device saturation at nearly all price points well in advance of less affluent countries where capital availability for 5G network roll-outs will dominate. ⇐ ⇐

Ookla! Opensignal! Cloudflare! Akamai! I beseech thee, hear my plea and take pity, oh mighty data collectors.

Whilst you report medians and averages (sometimes interchangeably, though I cannot speculate why), you've stopped publishing useable histogram information about the global situation, making the reports nearly useless for anything but telco marketing. Opensignal has stopped reporting meaningful 4G data at all, endangering any attempt at making sense.

Please, I beg of you, publish P50, P75, P90, and P95 results for each of your market reports! And about the global situation! Or reach out directly and share what you can in confidence so I can generate better guidance for web developers. ⇐

Samsung's lineup is not uniform worldwide, with many devices being region-specific. The closest modern (Western) Samsung device to the A51 is the Samsung A23 5G, which scores in the range of the Pixel 4a. As a result of the high CPU score and 5G modem, it's hard to recommend it — or any other current Samsung model — as a lab replacement. Try the Nokia G100 instead. ⇐

The idea that any of the publicly available data sets is globally representative should set off alarms.

The obvious problems include (but are not limited to):

- geographic differences in service availability and/or deployed infrastructure,

- differences in market penetration of observation platforms (e.g., was a system properly localised? Equally advertised?), and

- mandated legal gaps in coverage.

Of all the hand-waving we're doing to construct an estimate, this is the biggest leap and one of the hardest to triangulate against. ⇐

Why Are Tech Reporters Sleeping On The Biggest App Store Story?

The tech news is chockablock1 with antitrust rumblings and slow-motion happenings. Eagle-eyed press coverage, regulatory reports, and legal discovery have comprehensively documented the shady dealings of Apple and Google's app stores. Pressure for change has built to an unsustainable level. Something's gotta give.

This is the backdrop to the biggest app store story nobody is writing about: on pain of steep fines, gatekeepers are opening up to competing browsers. This, in turn, will enable competitors to replace app stores with directories of Progressive Web Apps. Capable browsers that expose web app installation and powerful features to developers can kickstart app portability, breaking open the mobile duopoly.

But you'd never know it reading Wired or The Verge.

With shockingly few exceptions, coverage of app store regulation assumes the answer to crummy, extractive native app stores is other native app stores. This unexamined framing shapes hundreds of pieces covering regulatory events, including by web-friendly authors. The tech press almost universally fails to mention the web as a substitute for native apps and fail to inform readers of its potential to disrupt app stores.

"An app is just a web-page wrapped in enough IP to make it a crime to defend yourself against corporate predation."

The implication is clear: browsers unchained can do to mobile what the web did to desktop, where more than 70% of daily "jobs to be done" happen on the web.

Replacing mobile app stores will look different than the web's path to desktop centrality, but the enablers are waiting in the wings. It has gone largely unreported that Progressive Web Apps (PWAs) have been held back by Apple and Google denying competing browsers access to essential APIs.2

Thankfully, regulators haven't been waiting on the press to explain the situation. Recent interventions into mobile ecosystems include requirements to repair browser choice, and the analysis backing those regulations takes into account the web's role as a potential competitor (e.g., Japan's JFTC (pdf)).

Regulators seem to understand that:

- App stores protect proprietary ecosystems through preferential discovery and capabilities.

- Stores then extract rents from developers dependent on commodity capabilities duopolists provide only through proprietary APIs.

- App portability threatens the proprietary agenda of app stores.

- The web can interrupt this model by bringing portability to apps and over-the-top discovery through search. This has yet to happen because...

- The duopolists, in different ways, have kneecapped competing browsers along with their own, keeping the web from contesting the role of app stores.

Apple and Google saw what the web did to desktop, and they've laid roadblocks to the competitive forces that would let history repeat on smartphones.

The Buried Lede

The web's potential to disrupt mobile is evident to regulators, advocates, and developers. So why does the tech news fail to explain the situation?

Consider just one of the many antitrust events of recent months. It was covered by The Verge, Mac Rumors, Apple Insider, and more.

None of the linked articles note browser competition's potential to upend app stores. Browsers unshackled have the potential to free businesses from build-it-twice proprietary ecosystems, end rapacious app store taxes, pave the way for new OS entrants — all without the valid security concerns side-loading introduces.

Lest you think this an isolated incident, this article on the impact of the EU's DMA lacks any hint of the web's potential to unseat app stores. You can repeat this trick with any DMA story from the past year. Or spot-check coverage of the NTIA's February report.

Reporters are "covering" these stories in the lightest sense of the word. Barrels of virtual ink has been spilt documenting unfair app store terms, conditions, and competition. And yet.

Disruption Disrupted

In an industry obsessed with "disruption," why is this David vs. Goliath story going untold? Some theories, in no particular order.

First, Mozilla isn't advocating for a web that can challenge native apps, and none of the other major browser vendors are telling the story either. Apple and Google have no interest in seeing their lucrative proprietary platforms supplanted, and Microsoft (your narrator's employer) famously lacks sustained mobile focus.

Next, it's hard to overlook that tech reporters live like wealthy people, iPhones and all. From that vantage point, it's often news that the web is significantly more capable on other OSes (never mind that they spend much of every day working in a desktop browser). It's hard to report on the potential of something you can't see for yourself.

Also, this might all be Greek. Reporters and editors aren't software engineers, so the potential of browser competition can remain understandably opaque. Stories that include mention of "alternative app stores" generally fail to mention that these stores may not be as safe, or that OS restrictions on features won't disappear just because of a different distribution mechanism, or that the security track records of the existing duopolist app stores are sketchy at best. Under these conditions, it's asking a lot to expect details-based discussion of alternatives, given the many technical wrinkles. Hopefully, someone can walk them through it.

Further, market contestability theory has only recently become a big part of the tech news beat. Regulators have been writing reports to convey their understanding of the market, and to shape effective legislation that will unchain the web, but smart folks unversed in both antitrust and browser minutiae might need help to pick up what regulators are putting down.

Lastly, it hasn't happened yet. Yes, Progressive Web Apps have been around for a few years, but they haven't had an impact on the iPhones that reporters and their circles almost universally carry. It's much easier to get folks to cover stories that directly affect them, and this is one that, so far, largely hasn't.

Green Shoots

The seeds of web-based app store dislocation have already been sown, but the chicken-and-egg question at the heart of platform competition looms.

On the technology side, Apple has been enormously successful at denying essential capabilities to the web through a strategy of compelled monoculture combined with strategic foot-dragging.