Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

I find them on the street & shadow.

It wasn’t until the end of our chat that I learned her name.

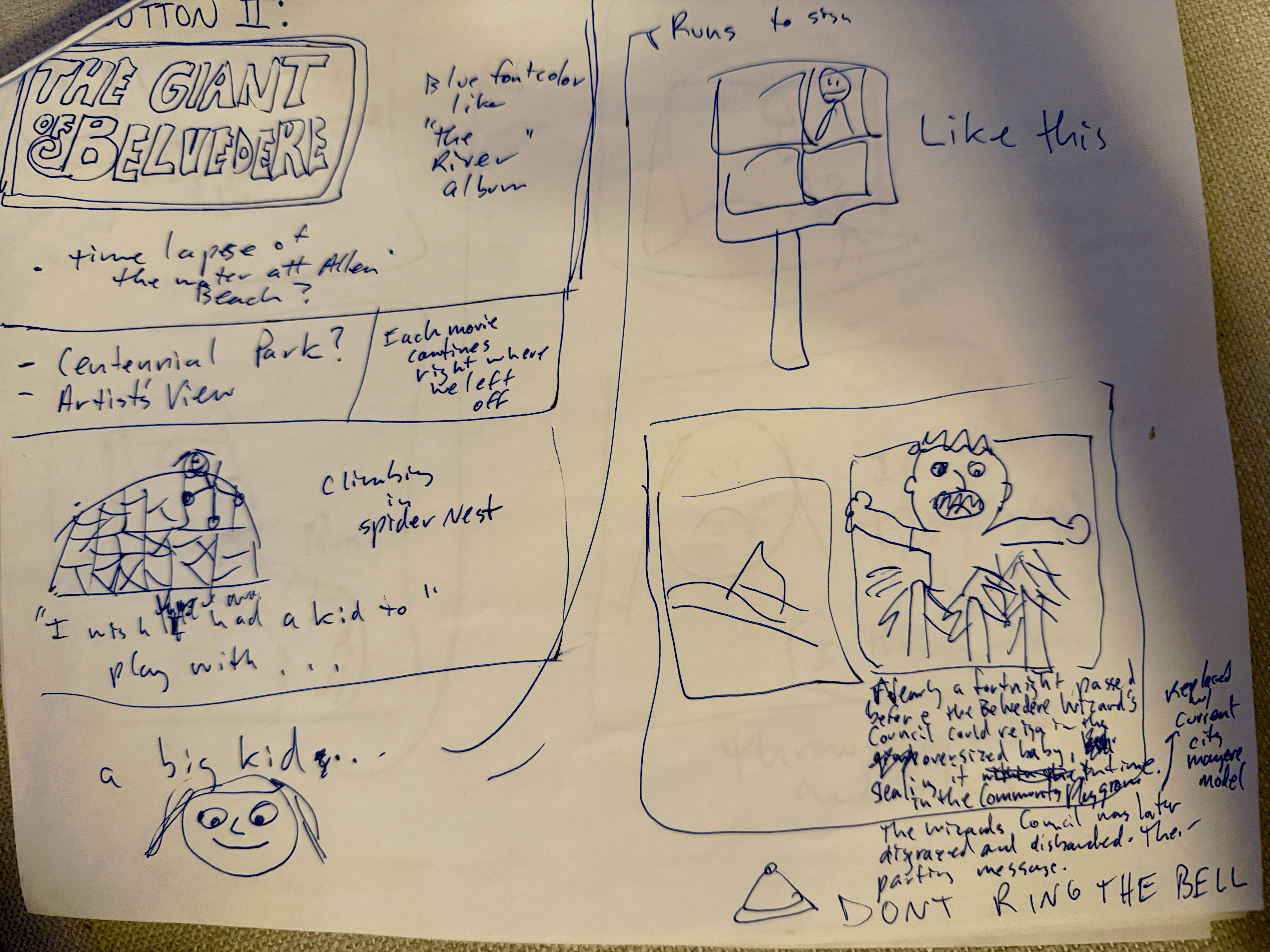

Red Button II: The Giant of Belvedere

We made another short film last year. Here's the "back of the DVD case" pitch:

Penny's back, and so's the Red Button, thankfully right where she left it. But who's this Giant? And why's he so cute?

Red Button II: The Giant of Belvedere is 2025 Belvedere Home-Made Film Festival Official Selection

A Harrington Production

- Tavie Harrington - "Penny"

- Bear Harrington - "The Giant"

- Carly Harrington - Hair, Makeup, Costume

- Charlie Harrington - Writer, Director, Composer, Editor

My favorite moment of the film festival when Tavie received her filmmaker's participation statue:

"I can't believe I won my first trophy!"

Watch the 3-minute film now:

I love having this continuing, annual project with Tavie (and now Bear, too). She keeps bringing it up, bursting with ideas for the next one.

Another thing I've been trying to do is learning one new movie-making technique each year, and then use it as a major part of that year's film. The first year was "reversing" a clip -- hello, Red Button's time travel mechanism. This year was green screen. I borrowed some green screens (aka sheets) from the local library and then we did our best to rig up Bear's bedroom like The Mandalorian's The Volume. After some hilarious (out)takes, I fired up YouTube Shorts and spend 25 seconds learning how to use DaVinci Resolve just enough to do the green screen clips. What a world. You can definitely tell that I'm doing this with less than a minute's worth of training with the Giant's glowing green hair, but I'm still blown away by how YouTube can teach you literally anything in less than a bathroom break.

I also tried to create a storyboard this year:

Would be fun to try some actual storyboarding software for 2026. Which reminds me to also look into comic book / graphic novel software, because Tavie's getting really into Dog Man at the moment.

Some other highlights

- Bear!!

- My mom (Tavie and Bear's Nana) visited from NJ and came to the film festival

- Getting clips and fake interviews with random park-walkers who happened to notice my "edits" to the historical plaques to incorporate the history of the Giant (watch the film to know what I'm talking about).

Making movies is fun!

Penny will return in 2026.

But will the Giant?

Who’s Going to Tell Them

Refactoring English: Month 13

New here?

Hi, I’m Michael. I’m a software developer and founder of small, indie tech businesses. I’m currently working on a book called Refactoring English: Effective Writing for Software Developers.

Every month, I publish a retrospective like this one to share how things are going with my book and my professional life overall.

Highlights

- I added regional pricing for my book based on purchasing power parity.

- I created my first Flutter app.

- I’m writing my first cross-language library.

Goal grades

At the start of each month, I declare what I’d like to accomplish. Here’s how I did against those goals: