Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Hot take: social platforms should disallow special character growth hacking

Reasons to use your shell's job control

Hello! Today someone on Mastodon asked about job control (fg, bg, Ctrl+z,

wait, etc). It made me think about how I don’t use my shell’s job

control interactively very often: usually I prefer to just open a new terminal

tab if I want to run multiple terminal programs, or use tmux if it’s over ssh.

But I was curious about whether other people used job control more often than me.

So I asked on Mastodon for reasons people use job control. There were a lot of great responses, and it even made me want to consider using job control a little more!

In this post I’m only going to talk about using job control interactively (not in scripts) – the post is already long enough just talking about interactive use.

what’s job control?

First: what’s job control? Well – in a terminal, your processes can be in one of 3 states:

- in the foreground. This is the normal state when you start a process.

- in the background. This is what happens when you run

some_process &: the process is still running, but you can’t interact with it anymore unless you bring it back to the foreground. - stopped. This is what happens when you start a process and then press

Ctrl+Z. This pauses the process: it won’t keep using the CPU, but you can restart it if you want.

“Job control” is a set of commands for seeing which processes are running in a terminal and moving processes between these 3 states

how to use job control

fgbrings a process to the foreground. It works on both stopped processes and background processes. For example, if you start a background process withcat < /dev/zero &, you can bring it back to the foreground by runningfgbgrestarts a stopped process and puts it in the background.- Pressing

Ctrl+zstops the current foreground process. jobslists all processes that are active in your terminalkillsends a signal (likeSIGKILL) to a job (this is the shell builtinkill, not/bin/kill)disownremoves the job from the list of running jobs, so that it doesn’t get killed when you close the terminalwaitwaits for all background processes to complete. I only use this in scripts though.- apparently in bash/zsh you can also just type

%2instead offg %2

I might have forgotten some other job control commands but I think those are all the ones I’ve ever used.

You can also give fg or bg a specific job to foreground/background. For example if I see this in the output of jobs:

$ jobs

Job Group State Command

1 3161 running cat < /dev/zero &

2 3264 stopped nvim -w ~/.vimkeys $argv

then I can foreground nvim with fg %2. You can also kill it with kill -9 %2, or just kill %2 if you want to be more gentle.

how is kill %2 implemented?

I was curious about how kill %2 works – does %2 just get replaced with the

PID of the relevant process when you run the command, the way environment

variables are? Some quick experimentation shows that it isn’t:

$ echo kill %2

kill %2

$ type kill

kill is a function with definition

# Defined in /nix/store/vicfrai6lhnl8xw6azq5dzaizx56gw4m-fish-3.7.0/share/fish/config.fish

So kill is a fish builtin that knows how to interpret %2. Looking at

the source code (which is very easy in fish!), it uses jobs -p %2 to expand %2

into a PID, and then runs the regular kill command.

on differences between shells

Job control is implemented by your shell. I use fish, but my sense is that the basics of job control work pretty similarly in bash, fish, and zsh.

There are definitely some shells which don’t have job control at all, but I’ve only used bash/fish/zsh so I don’t know much about that.

Now let’s get into a few reasons people use job control!

reason 1: kill a command that’s not responding to Ctrl+C

I run into processes that don’t respond to Ctrl+C pretty regularly, and it’s

always a little annoying – I usually switch terminal tabs to find and kill and

the process. A bunch of people pointed out that you can do this in a faster way

using job control!

How to do this: Press Ctrl+Z, then kill %1 (or the appropriate job number

if there’s more than one stopped/background job, which you can get from

jobs). You can also kill -9 if it’s really not responding.

reason 2: background a GUI app so it’s not using up a terminal tab

Sometimes I start a GUI program from the command line (for example with

wireshark some_file.pcap), forget to start it in the background, and don’t want it eating up my terminal tab.

How to do this:

- move the GUI program to the background by pressing

Ctrl+Zand then runningbg. - you can also run

disownto remove it from the list of jobs, to make sure that the GUI program won’t get closed when you close your terminal tab.

Personally I try to avoid starting GUI programs from the terminal if possible

because I don’t like how their stdout pollutes my terminal (on a Mac I use

open -a Wireshark instead because I find it works better but sometimes you

don’t have another choice.

reason 2.5: accidentally started a long-running job without tmux

This is basically the same as the GUI app thing – you can move the job to the background and disown it.

I was also curious about if there are ways to redirect a process’s output to a file after it’s already started. A quick search turned up this Linux-only tool which is based on nelhage’s reptyr (which lets you for example move a process that you started outside of tmux to tmux) but I haven’t tried either of those.

reason 3: running a command while using vim

A lot of people mentioned that if they want to quickly test something while

editing code in vim or another terminal editor, they like to use Ctrl+Z

to stop vim, run the command, and then run fg to go back to their editor.

You can also use this to check the output of a command that you ran before

starting vim.

I’ve never gotten in the habit of this, probably because I mostly use a GUI version of vim. I feel like I’d also be likely to switch terminal tabs and end up wondering “wait… where did I put my editor???” and have to go searching for it.

reason 4: preferring interleaved output

A few people said that they prefer to the output of all of their commands being interleaved in the terminal. This really surprised me because I usually think of having the output of lots of different commands interleaved as being a bad thing, but one person said that they like to do this with tcpdump specifically and I think that actually sounds extremely useful. Here’s what it looks like:

# start tcpdump

$ sudo tcpdump -ni any port 1234 &

tcpdump: data link type PKTAP

tcpdump: verbose output suppressed, use -v[v]... for full protocol decode

listening on any, link-type PKTAP (Apple DLT_PKTAP), snapshot length 524288 bytes

# run curl

$ curl google.com:1234

13:13:29.881018 IP 192.168.1.173.49626 > 142.251.41.78.1234: Flags [S], seq 613574185, win 65535, options [mss 1460,nop,wscale 6,nop,nop,TS val 2730440518 ecr 0,sackOK,eol], length 0

13:13:30.881963 IP 192.168.1.173.49626 > 142.251.41.78.1234: Flags [S], seq 613574185, win 65535, options [mss 1460,nop,wscale 6,nop,nop,TS val 2730441519 ecr 0,sackOK,eol], length 0

13:13:31.882587 IP 192.168.1.173.49626 > 142.251.41.78.1234: Flags [S], seq 613574185, win 65535, options [mss 1460,nop,wscale 6,nop,nop,TS val 2730442520 ecr 0,sackOK,eol], length 0

# when you're done, kill the tcpdump in the background

$ kill %1

I think it’s really nice here that you can see the output of tcpdump inline in your terminal – when I’m using tcpdump I’m always switching back and forth and I always get confused trying to match up the timestamps, so keeping everything in one terminal seems like it might be a lot clearer. I’m going to try it.

reason 5: suspend a CPU-hungry program

One person said that sometimes they’re running a very CPU-intensive program,

for example converting a video with ffmpeg, and they need to use the CPU for

something else, but don’t want to lose the work that ffmpeg already did.

You can do this by pressing Ctrl+Z to pause the process, and then run fg

when you want to start it again.

reason 6: you accidentally ran Ctrl+Z

Many people replied that they didn’t use job control intentionally, but

that they sometimes accidentally ran Ctrl+Z, which stopped whatever program was

running, so they needed to learn how to use fg to bring it back to the

foreground.

The were also some mentions of accidentally running Ctrl+S too (which stops

your terminal and I think can be undone with Ctrl+Q). My terminal totally

ignores Ctrl+S so I guess I’m safe from that one though.

reason 7: already set up a bunch of environment variables

Some folks mentioned that they already set up a bunch of environment variables that they need to run various commands, so it’s easier to use job control to run multiple commands in the same terminal than to redo that work in another tab.

reason 8: it’s your only option

Probably the most obvious reason to use job control to manage multiple processes is “because you have to” – maybe you’re in single-user mode, or on a very restricted computer, or SSH’d into a machine that doesn’t have tmux or screen and you don’t want to create multiple SSH sessions.

reason 9: some people just like it better

Some people also said that they just don’t like using terminal tabs: for instance a few folks mentioned that they prefer to be able to see all of their terminals on the screen at the same time, so they’d rather have 4 terminals on the screen and then use job control if they need to run more than 4 programs.

I learned a few new tricks!

I think my two main takeaways from thos post is I’ll probably try out job control a little more for:

- killing processes that don’t respond to Ctrl+C

- running

tcpdumpin the background with whatever network command I’m running, so I can see both of their output in the same place

Forget “show, don’t tell”. Engage, don’t show!

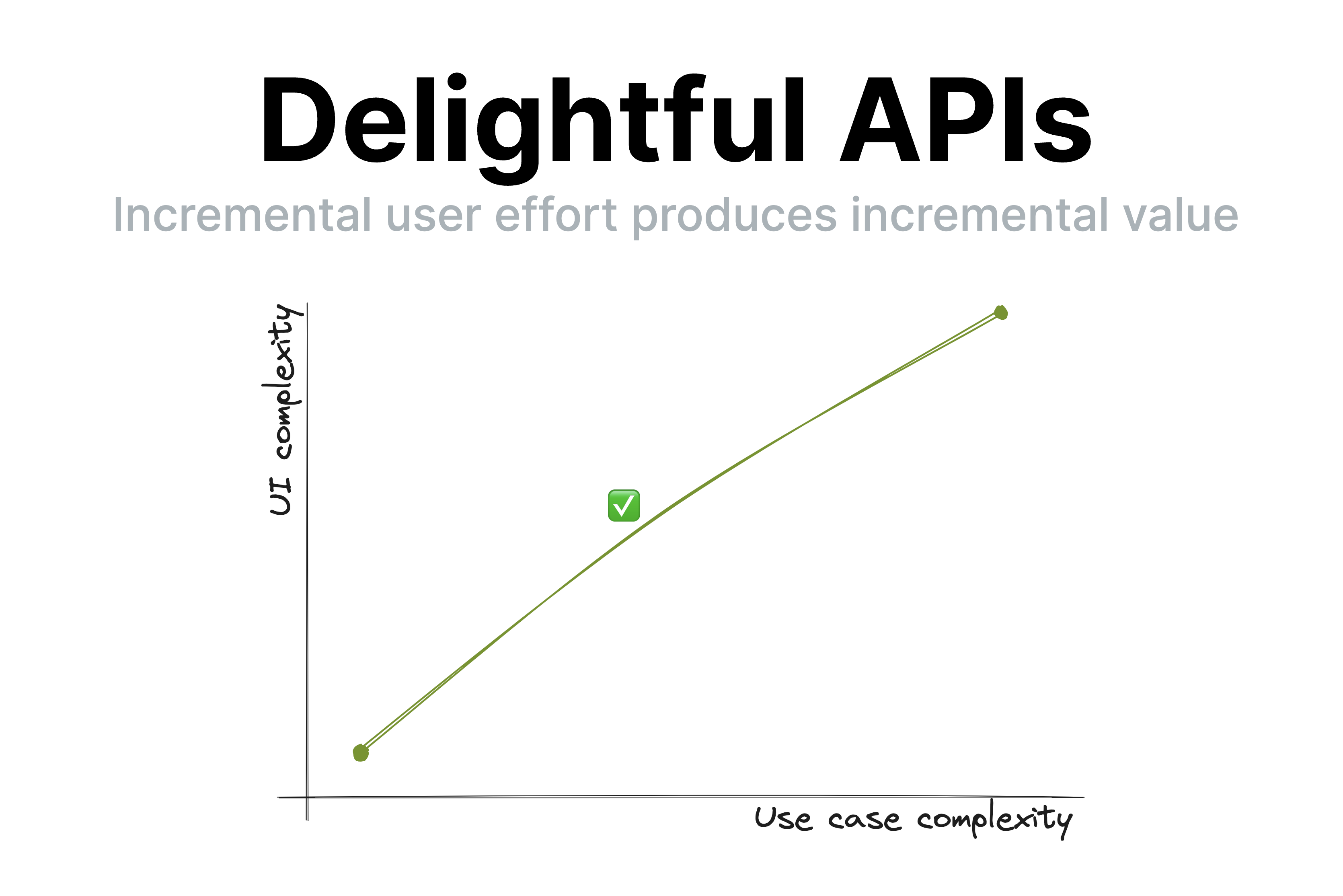

A few days ago, I gave a very well received talk about API design at dotJS titled “API Design is UI Design” [1]. One of the points I made was that good UIs (and thus, good APIs) have a smooth UI complexity to Use case complexity curve. This means that incremental user effort results in incremental value; at no point going just a little bit further requires a disproportionately big chunk of upfront work [2].

Observing my daughter’s second ever piano lesson today made me realize how this principle extends to education and most other kinds of knowledge transfer (writing, presentations, etc.). Her (generally wonderful) teacher spent 40 minutes teaching her notation, longer and shorter notes, practicing drawing clefs, etc. Despite his playful demeanor and her general interest in the subject, she was clearly distracted by the end of it.

It’s easy to dismiss this as a 5 year old’s short attention span, but I could tell what was going on: she did not understand why these were useful, nor how they connect to her end goal, which is to play music. To her, notation was just an assortment of arbitrary symbols and lines, some of which she got to draw. Note lengths were just isolated sounds with no connection to actual music. Once I connected note lengths to songs she has sung with me and suggested they try something more hands on, her focus returned instantly.

I mentioned to her teacher that kids that age struggle to learn theory for that long without practicing it. He agreed, and said that many kids are motivated to get through the theory because they’ve heard their teacher play nice music and want to get there too. The thing is… sure, that’s motivating. But as far as motivations go, it’s pretty weak.

Humans are animals, and animals don’t play the long game, or they would die. We are programmed to optimize for quick, easy dopamine hits. The farther into the future the reward, the more discipline it takes to stay motivated and put effort towards it. This applies to all humans, but even more to kids and ADHD folks [3]. That’s why it’s so hard for teenagers to study so they can improve their career opportunities and why you struggle to eat well and exercise so you can be healthy and fit.

So how does this apply to knowledge transfer? It highlights how essential it is for students to a) understand why what they are learning is useful and b) put it in practice ASAP. You can’t retain information that is not connected to an obvious purpose [4] — your brain will treat it as noise and discard it.

The thing is, the more expert you are on a topic, the harder these are to do when conveying knowledge to others. I get it. I’ve done it too. First, the purpose of concepts feels obvious to you, so it’s easy to forget to articulate it. You overestimate the student’s interest in the minutiae of your field of expertise. Worse yet, so many concepts feel essential that you are convinced nothing is possible without learning them (or even if it is, it’s just not The Right Way™). Looking back on some of my earlier CSS lectures, I’ve definitely been guilty of this.

As educators, it’s very tempting to say “they can’t possibly practice before understanding X, Y, Z, they must learn it properly”. Except …they won’t. At best they will skim over it until it’s time to practice, which is when the actual learning happens. At worst, they will give up. You will get much better retention if you frequently get them to see the value of their incremental imperfect knowledge than by expecting a big upfront attention investment before they can reap the rewards.

There is another reason to avoid long chunks of upfront theory: humans are goal oriented. When we have a goal, we are far more motivated to absorb information that helps us towards that goal. The value of the new information is clear, we are practicing it immediately, and it is already connected to other things we know.

This means that explaining things in context as they become relevant is infinitely better for retention and comprehension than explaining them upfront. When knowledge is a solution to a problem the student is already facing, its purpose is clear, and it has already been filtered by relevance. Furthermore, learning it provides immediate value and instant gratification: it explains what they are experiencing or helps them achieve an immediate goal.

Even if you don’t teach, this still applies to you. I would go as far as to say it applies to every kind of knowledge transfer: teaching, writing documentation, giving talks, even just explaining a tricky concept to your colleague over lunch break. Literally any activity that involves interfacing with other humans benefits from empathy and understanding of human nature and its limitations.

To sum up:

- Always explain why something is useful. Yes, even when it’s obvious to you.

- Minimize the amount of knowledge you convey before the next opportunity to practice it. For non-interactive forms of knowledge transfer (e.g. a book), this may mean showing an example, whereas for interactive ones it could mean giving the student a small exercise or task. Even in non-interactive forms, you can ask questions — the receiver will still pause and think what they would answer even if you are not there to hear it.

- Prefer explaining in context rather than explaining upfront.

“Show, don’t tell”? Nah. More like “Engage, don’t show”.

(In the interest of time, I’m posting this without citations to avoid going down the rabbit hole of trying to find the best source for each claim, especially since I believe they’re pretty uncontroversial in the psychology / cognitive science literature. That said, I’d love to add references if you have good ones!)

The video is now available on YouTube: API Design is UI Design ↩︎

When it does, this is called a usability cliff. ↩︎

I often say that optimizing UX for people with ADHD actually creates delightful experiences even for those with neurotypical attention spans. Just because you could focus your attention on something you don’t find interesting doesn’t mean you enjoy it. Yet another case of accessibility helping everyone! ↩︎

I mean, you can memorize anything if you try hard enough, but by optimizing teaching we can keep rote memorization down to the bare minimum. ↩︎

Configure a Git Shell Prompt Under Nix

I recently read Julia Evans’ latest zine about git, and one of her tips was to configure your terminal shell prompt to show the git status.

Julia’s terminal prompt looks like this:

main is Julia’s current git branch. When she’s in the middle of a git operation like bisect or merge, the terminal changes to this:

It had never occurred to me to customize my shell prompt, but I immediately recognized the value.