Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

I fell for a phishing attack and lost access to my X account. Here are five mistakes I did that you need to avoid!

I fell for a phishing mail and lost access to Twitter/X

Perception and cognition lecture notes

This past Tuesday we had a lecture on perception and cognition as part of the Good and Bad Science course I’m taking. My rough notes are below.

Notes on clarifying man pages

Hello! After spending some time working on the Git man pages last year, I’ve been thinking a little more about what makes a good man page.

I’ve spent a lot of time writing cheat sheets for tools (tcpdump, git, dig, etc) which have a man page as their primary documentation. This is because I often find the man pages hard to navigate to get the information I want.

Lately I’ve wondering – could the man page itself have an amazing cheat sheet in it? What might make a man page easier to use? I’m still very early in thinking about this but I wanted to write down some quick notes.

I asked some people on Mastodon for their favourite man pages, and here are some examples of interesting things I saw on those man pages.

an OPTIONS SUMMARY

If you’ve read a lot of man pages you’ve probably seen something like this in

the SYNOPSIS: once you’re listing almost the entire alphabet, it’s hard

ls [-@ABCFGHILOPRSTUWabcdefghiklmnopqrstuvwxy1%,]

grep [-abcdDEFGHhIiJLlMmnOopqRSsUVvwXxZz]

The rsync man page has a solution I’ve never seen before: it keeps its SYNOPSIS very terse, like this:

Local:

rsync [OPTION...] SRC... [DEST]

and then has an “OPTIONS SUMMARY” section with a 1-line summary of each option, like this:

--verbose, -v increase verbosity

--info=FLAGS fine-grained informational verbosity

--debug=FLAGS fine-grained debug verbosity

--stderr=e|a|c change stderr output mode (default: errors)

--quiet, -q suppress non-error messages

--no-motd suppress daemon-mode MOTD

Then later there’s the usual OPTIONS section with a full description of each option.

an OPTIONS section organized by category

The strace man page organizes its options by category (like “General”, “Startup”, “Tracing”, and “Filtering”, “Output Format”) instead of alphabetically.

As an experiment I tried to take the grep man page and make an

“OPTIONS SUMMARY” section grouped by category, you can see the results

here. I’m not

sure what I think of the results but it was a fun exercise. When I was writing

that I was thinking about how I can never remember the name of the -l grep

option. It always takes me what feels like forever to find it in the man page

and I was trying to think of what structure would make it easier for me to find.

Maybe categories?

a cheat sheet

A couple of people pointed me to the suite of Perl man pages (perlfunc, perlre, etc), and one thing I

noticed was man perlcheat, which has

cheat sheet sections like this:

SYNTAX

foreach (LIST) { } for (a;b;c) { }

while (e) { } until (e) { }

if (e) { } elsif (e) { } else { }

unless (e) { } elsif (e) { } else { }

given (e) { when (e) {} default {} }

I think this is so cool and it makes me wonder if there are other ways to write condensed ASCII 80-character-wide cheat sheets for use in man pages.

examples are very popular

A common comment was something to the effect of “I like any man page that has examples”. Someone mentioned the OpenBSD man pages, and the openbsd tail man page has examples of the exact 2 ways I use tail at the end.

I think I’ve most often seen the EXAMPLES section at the end of the man page, but some man pages (like the rsync man page from earlier) start with the examples. When I was working on the git-add and git rebase man pages I put a short example at the beginning.

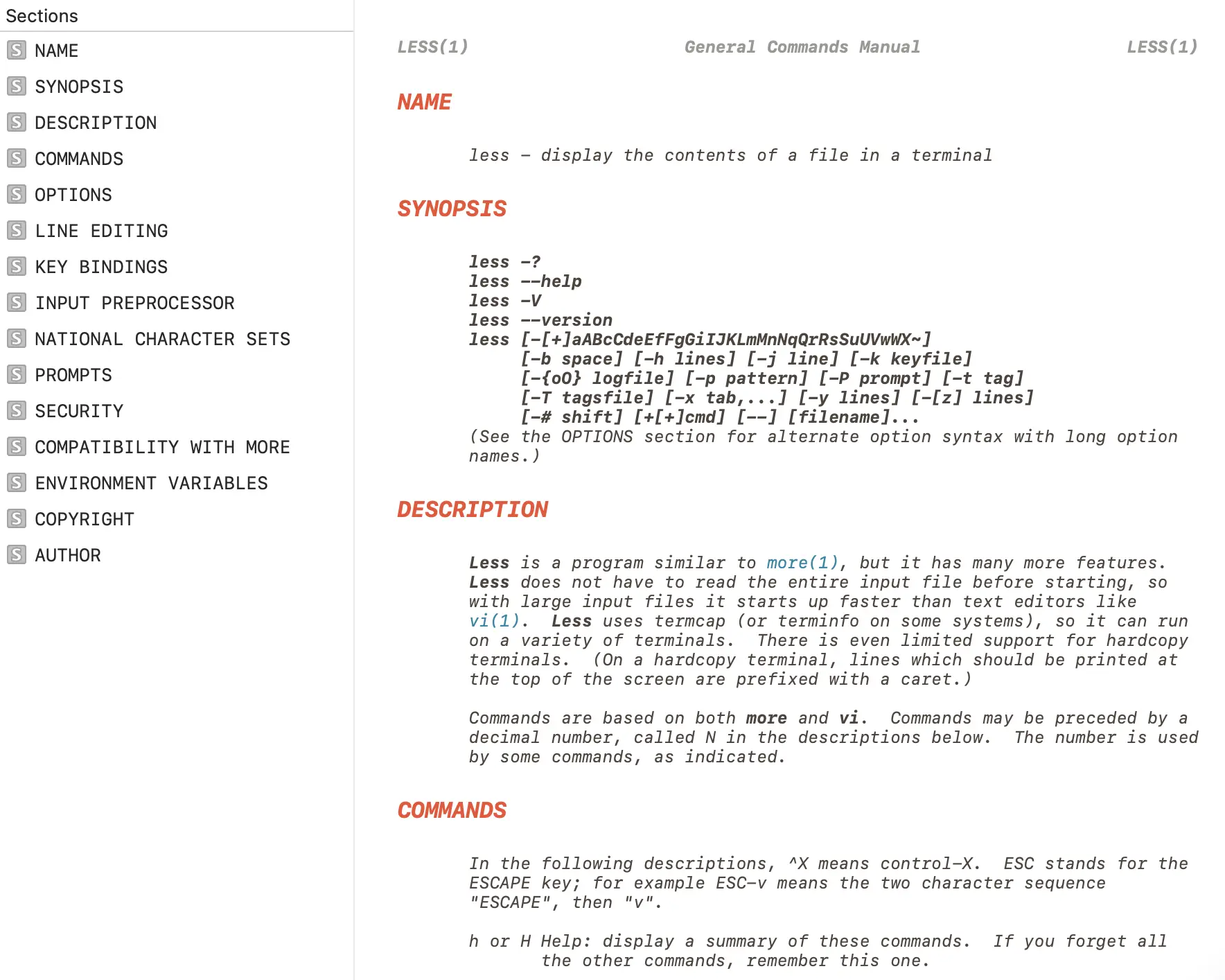

a table of contents, and links between sections

This isn’t a property of the man page itself, but one issue with man pages in the terminal is it’s hard to know what sections the man page has.

When working on the Git man pages, one thing Marie and I did was to add a table of contents to the sidebar of the HTML versions of the man pages hosted on the Git site.

I’d also like to add more hyperlinks to the HTML versions of the Git man pages at some point, so that you can click on “INCOMPATIBLE OPTIONS” to get to that section. It’s very easy to add links like this in the Git project since Git’s man pages are generated with AsciiDoc.

I think adding a table of contents and adding internal hyperlinks is kind of a nice middle ground where we can make some improvements to the man page format (in the HTML version of the man page at least) without maintaining a totally different form of documentation. Though for this to work you do need to set up a toolchain like Git’s AsciiDoc system.

It would be amazing if there were some kind of universal system to make it easy

to look up a specific option in a man page (“what does -a do?”).

The best trick I know is use the man pager to search for something like ^ *-a

but I never remember to do it and instead just end up going through

every instance of -a in the man page until I find what I’m looking for.

examples for every option

The curl man page has examples for every option, and there’s also a table of contents on the HTML version so you can more easily jump to the option you’re interested in.

For instance the example for --cert makes it easy to see that you likely also want to pass the --key option, like this:

curl --cert certfile --key keyfile https://example.com

The way they implement this is that there’s [one file for each option](https://github.com/curl/curl/blob/dc08922a61efe546b318daf964514ffbf41583 25/docs/cmdline-opts/append.md) and there’s an “Example” field in that file.

formatting data in a table

Quite a few people said that man ascii was their favourite man page, which looks like this:

Oct Dec Hex Char

───────────────────────────────────────────

000 0 00 NUL '\0' (null character)

001 1 01 SOH (start of heading)

002 2 02 STX (start of text)

003 3 03 ETX (end of text)

004 4 04 EOT (end of transmission)

005 5 05 ENQ (enquiry)

006 6 06 ACK (acknowledge)

007 7 07 BEL '\a' (bell)

010 8 08 BS '\b' (backspace)

011 9 09 HT '\t' (horizontal tab)

012 10 0A LF '\n' (new line)

Obviously man ascii is an unusual man page but I think what’s cool about this man page (other than the fact that it’s always

useful to have an ASCII reference) is it’s very easy to scan to find the

information you need because of the table format. It makes me wonder if there

are more opportunities to display information in a “table” in a man page to make

it easier to scan.

the GNU approach

When I talk about man pages it often comes up that the GNU coreutils man pages (for example man tail) don’t have examples, unlike the OpenBSD man pages, which do have examples.

I’m not going to get into this too much because it seems like a fairly political topic and I definitely can’t do it justice here, but here are some things I believe to be true:

- The GNU project prefers to maintain documentation in “info” manuals instead of man pages. This page says “the man pages are no longer being maintained”.

- There are 3 ways to read “info” manuals: their HTML version, in Emacs, or with a standalone

infotool. I’ve heard from some Emacs users that they like the Emacs info browser. I don’t think I’ve ever talked to anyone who uses the standaloneinfotool. - The info manual entry for tail is linked at the bottom of the man page, and it does have examples

- The FSF used to sell print books of the GNU software manuals (and maybe they still do sometimes?)

After a certain level of complexity a man page gets really hard to navigate: while I’ve never used the coreutils info manual and probably won’t, I would almost certainly prefer to use the GNU Bash reference manual or the The GNU C Library Reference Manual via their HTML documentation rather than through a man page.

a few more man-page-adjacent things

Here are some tools I think are interesting:

- The fish shell comes with a Python script to automatically generate tab completions from man pages

- tldr.sh is a community maintained database of examples, for example you can run it as

tldr grep. Lots of people have told me they find it useful. - the Dash Mac docs browser has a nice man page viewer in it. I still use the terminal man page viewer but I like that it includes a table of contents, it looks like this:

it’s interesting to think about a constrained format

Man pages are such a constrained format and it’s fun to think about what you can do with such limited formatting options.

Even though I’m very into writing I’ve always had a bad habit of never reading documentation and so it’s a little bit hard for me to think about what I actually find useful in man pages, I’m not sure whether I think most of the things in this post would improve my experience or not. (Except for examples, I LOVE examples)

So I’d be interested to hear about other man pages that you think are well designed and what you like about them, the comments section is here.